By Mason B. Webb

Just when one thinks that there could not be another “untold” story about World War II, along comes a writer like Dan Kurzman with a new book about a previously untold story: the Nazis’ plan to kidnap Pope Pius XII. So fast paced and well told is A Special Mission: Hitler’s Secret Plot to Seize the Vatican and Kidnap Pope Pius XII (Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2006, 304 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $26.00, hardcover) that it seems like a fictional plot—a worthy follow-up to The DaVinci Code. Yet, it is all true.

In A Special Mission, Kurzman details the operation. SS General Karl Wolff, in the wake of Mussolini’s ouster and Italy’s capitulation to the Allies in September 1943, is sent to Italy by Hitler to carry out an audacious plan—occupy the Vatican and kidnap the Pope.

In A Special Mission, Kurzman details the operation. SS General Karl Wolff, in the wake of Mussolini’s ouster and Italy’s capitulation to the Allies in September 1943, is sent to Italy by Hitler to carry out an audacious plan—occupy the Vatican and kidnap the Pope.

Kurzman tells the tale convincingly, writing, “Berlin Radio warned of ‘severe measures unless the pope accepts the policies of Hitler and Italian fascism.’ All food stocks were seized, with Vatican rations halved; postal facilities from the Vatican were cut off; and telephone lines to Rome were tapped—all taking place even as [Ambassador Ernst von] Weizsäcker was told to assure the Vatican that the Germans would ‘protect the Vatican City from the fighting.’ The ambassador, who by now knew of Wolff’s mission, was more apprehensive than ever.”

To get to the heart of the story, Kurzman interviewed General Wolff following his release from prison in May 1945—the only journalist to have done so.

The fact that Wolff never carried out the plan is obvious. How he avoided doing it forms the crux of this exciting, fast-paced narrative. Wolff and his co-conspirators persuaded the Pope to maintain his silence about the impending roundup of Rome’s Jews and their transport to Auschwitz, arguing that it could save both his life and the treasures of the Vatican as well as soften the blow against the Jewish community. Pius XII’s decision not to criticize the ongoing Holocaust is well known (and is discussed at length by Kurzman); the story of the kidnap plot adds a new layer to that discussion.

A Special Mission is the first book to tell this remarkable, almost unbelievable, story and is vital for understanding the Vatican’s controversial wartime activities—including the Pope’s refusal to speak out forcefully against the slaughter of the Jews—which remain controversial to this day. The only question is why it took so long for this story to come out.

Berlin Games: How the Nazis Stole the Olympic Dream, by Guy Walters, William Morrow, New York, 2006, 368 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Berlin Games: How the Nazis Stole the Olympic Dream, by Guy Walters, William Morrow, New York, 2006, 368 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $24.95, hardcover.

The Nazis almost pulled off the impossible.

In 1936, Germany hosted both the Winter (in Garmisch-Partenkirchen) and Summer (in Berlin) Olympic Games, nearly convincing the world that the Nazi regime was no threat to mankind. Nearly.

In Berlin Games, British author Guy Walters, armed with a staggering amount of research, recreates those heady, prewar days when the world’s biggest sporting pageant was held in a country that, within three years, would launch a new and terrible global catastrophe.

The 1936 Olympics were nothing less than the most political sporting event of the 20th century. Far from being merely a friendly contest of amateur athletes, it was an epic clash between proponents of evil and those on the side of civilization.

Hitler and his minions did their best to present their kindest face to the millions who came to Germany that year. Visitors from everywhere marveled at the new Germany, so different from the Germany they had read about in the papers. Gone (for a few months, anyway) were the signs of anti-Semetism. The anti-Jewish newspapers took a hiatus; the placards urging Germans not to buy from Jewish merchants mysteriously (but temporarily) disappeared. The Germany that Hitler wanted everyone to see was clean, prosperous, orderly. The Germans seemed happy and carefree, belying all the stories about atrocities and persecution that began in 1933—stories that were dismissed as mere fiction dreamed up by journalists with an anti-German ax to grind.

As Walters writes about the opening of the Winter Games, “Although many were excited by the ten days’ sport that lay ahead of them, most of the crowd were more thrilled by the imminent arrival of the star of the show— Adolf Hitler. The spectators could hear the cheers greeting Hitler, quiet at first, and then increasing in volume, as his train from Munich approached. ‘You could hear the ‘Sieg Heil! Sieg Heil!’ coming up the valley when he arrived,’ Albert Washburn recalled. For the few American visitors, it was hard not to get caught up in the excitement—Washburn even stuck his arm out. His wife did the same…. The Fuehrer had overshadowed the event before it had started.”

Berlin Games is the complete, fascinating history of both the 1936 Winter and Summer games; how the Nazis went to great lengths to obscure the sinister truth about what was going on within Germany’s borders; how Hitler attempted to use the games as a model of Aryan supremacy and Nazi efficiency; and how Avery Brundage and the International Olympic Committee bent over backward to keep from offending the host nation. It is an outstanding, truly important work.

Jimmy Stewart, Bomber Pilot, by Starr Smith, Zenith Press, St. Paul, Minn., 2006, 288 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $14.95, softcover.

Jimmy Stewart, Bomber Pilot, by Starr Smith, Zenith Press, St. Paul, Minn., 2006, 288 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $14.95, softcover.

It goes without saying that James Maitland Stewart was one of Hollywood’s greatest and most enduring stars. But, he was also an American patriot of the first order.

Giving up his safe, glamorous life in Tinseltown for a rugged and uncertain future at the controls of bombers over occupied Europe, Stewart was an inspiration to an entire generation of Americans who wanted to serve their country, no matter what the cost.

Veteran journalist Starr Smith has captured the true essence of the man in this superbly written and profusely illustrated biography. In March 1941, the 33-year-old Stewart, although already an established star making thousands of dollars a month, enlisted in the Air Corps, for which he was paid $21 per month. After becoming an officer, the affable Stewart won swift promotions, flew 20 combat missions, became commander of the 703rd Bomb Squadron of the 445th Bomb Group, then was promoted to full colonel and, after several other posts, commander of the 2nd Combat Bomb Wing. Eventually he would spend 27 years on active and reserve service, including flying missions over Vietnam. In 1968, he retired from the Air Force as a brigadier general at age 60.

Smith also touches on the last phase of Stewart’s remarkable life and military career, when he flew combat missions in B-52s during the Vietnam War, a war in which his stepson, Lieutenant Ron McLean, was killed. Stewart frequently told reporters that his military experiences were “much greater” than those associated with a movie star’s career.

Stewart’s daughter Kelly pays a fine tribute to him at the book’s opening: “My father’s experiences during World War II affected him more deeply and permanently that anything else in his life. Yet his children grew up knowing almost nothing about those years. Dad never talked about the war. My siblings and I knew only that he had been a pilot and that he had won some medals, but that he didn’t see himself as a hero. He saw only that he had done his duty…. I know that the war held terrible memories for my father, as it must for anyone who lived through the combat. But he was also deeply proud to have served his country.”

With so many of the current generation of Hollywood stars decidedly antiwar and anti-military, this book is a refreshing, nostalgic look back at a time when personal fame, money, and safety took a back seat to the ideals of duty, honor, and country. Not to be missed.

The Crash of Little Eva, by Barry Ralph, Pelican, Gretna, La., 2006, 209 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, $18.95, softcover.

The Crash of Little Eva, by Barry Ralph, Pelican, Gretna, La., 2006, 209 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, $18.95, softcover.

The story of Little Eva, an American B-24 bomber from the 321st Squadron, 90th Bomb Group, stationed at a remote U.S. air base in far northern Queensland, is eerily similar to that of the Lady Be Good, a B-24 that became lost over the Mediterranean and crashed in the North African desert. Its crew wandered for days before finally succumbing to the harsh elements. Their remains were found decades later.

In Little Eva’s case, she took off from her base on her maiden combat mission on December 1, 1942, with 23 other B-24s from her group on a mission to attack Japanese naval targets near eastern New Guinea. But something went amiss during the bomb run. The plane’s bomb rack malfunctioned, and she tried going around again. Separated from the rest of the group, and slammed by an unexpected tropical storm and the sudden onset of night, the navigator became confused and completely lost. With fuel running low, the pilot made the decision to abandon ship. All the crewmen—or so the pilot thought—bailed out.

Little Eva crash-landed in the wilds of northern Australia, not far from the coast, with three crewmen still on board. Some of the survivors managed to be rescued, but others straggled on, using their wits to stay alive, searching desperately for food and water in the unbearably hot climate, trying to avoid poisonous snakes, man-eating crocodiles, hungry mosquitoes, and deadly, swiftly flowing rivers.

Basing much of his research on detailed police reports of the search for the plane and survivors by American and Australian authorities, Barry Ralph, an Australian broadcast journalist and military historian, takes the reader along on the search.

The Crash of Little Eva is a spellbinding story of courage, survival, and the will to live, one of the best of its genre, and a book that will not easily be forgotten.

D-Day Survivor: An Autobiography, by Harold Baumgarten, Pelican, Gretna, La., 2006, 256 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $25.00, hardcover.

D-Day Survivor: An Autobiography, by Harold Baumgarten, Pelican, Gretna, La., 2006, 256 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $25.00, hardcover.

What was the Allied invasion of France really like? One way to find out is to listen to a veteran of that operation. And few veterans have told the story of that cold, gray June morning better than Harold Baumgarten, then a young soldier with the 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division.

Few units suffered more on June 6, 1944, than the 116th, and few soldiers suffered more and lived than Baumgarten, the Jewish son of Austrian parentage. Wounded five times within a span of 32 hours, he continued to press forward into the fire, not willing to give up on the mission he had worked so hard to take part in.

The book begins with the author’s tough upbringing in New York and follows his dream to play baseball for the Yankees, his being drafted into the Army in 1943, his basic training, and his preparations for D-Day in England. He recounts the frightening hours before and during the landing at Omaha Beach as he battled ashore, and his being wounded numerous times by bullets and shell fragments.

After being ambushed near Vierville and badly hurt, Baumgarten recalled, “At 3:00 am [on June 7] I felt like I was dying. I was cold and clammy and had a ‘needles and pins’ feeling throughout my whole body. I was awake, with no severe pain, even though I had been wounded four times in the last twenty hours. The last time I had eaten anything was more than thirty hours earlier. I kept drinking water from canteens that were no longer of any use to their owners.”

Baumgarten was finally rescued by an ambulance crew, but his ordeal was not yet over, for the medics, too, came under enemy fire, and he was wounded again. After recovering from his wounds, he was discharged from the Army and returned to rebuild his war-shattered life; he became a physician. Many years later, Stephen Ambrose learned of Baumgarten’s adventures and featured him in his epic book, D-Day: 6 June 1944. Feted at gatherings and reunions of the 29th Division, Baumgarten soon became fast friends with Ambrose, Steven Spielberg, and Tom Hanks, the latter two who would be responsible for making Saving Private Ryan.

Baumgarten believes that his life was spared so that he could give a face and a voice to his fellow brave Americans who lost their lives that day. Determined to make his autobiography a testament to those men who made the ultimate sacrifice for victory, Baumgarten’s story ensures that the memory of the buddies he left behind on the bloody sands of the Dog Green sector of Omaha Beach will never be forgotten.

The Germans in Normandy, by Richard Hargreaves, Casemate, Barnsley, England, 2006, 271 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover.

The Germans in Normandy, by Richard Hargreaves, Casemate, Barnsley, England, 2006, 271 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover.

Most accounts of the Normandy invasion are told from an American, British, and Canadian point of view; very little draws upon German accounts of the battle. But, at last comes a book that draws heavily on German sources. In this splendid new work, Richard Hargreaves, a British journalist who spent 15 years researching it, presents the planning, the battle, and the aftermath as the enemy saw it.

Using letters, diaries, firsthand accounts, unit histories, newspaper articles, and official records, plus a host of secondary sources, Hargreaves gives the reader a penetrating look into the lives of the men—both high- and low-ranking—who manned Hitler’s vaunted Atlantic Wall, men who believed both in their cause and their ability to throw any Allied invasion back into the sea.

But belief in victory quickly turned to disappointment, and then to disaster. Within 48 hours of the start of the invasion, it was clear to the Germans that they would not be able to hold back the inexorable Allied tide, that their cause was doomed. Hargreaves details the Germans’ frantic effort to hold back that tide—delaying actions in the towns and villages of Normandy, the failed counterthrust at Mortain, the horrific casualties at the Falaise Gap, the loss of Paris, the retreat to the Rhine.

On July 18, 1944, an unprecedented Allied saturation bombing of German lines near Caen was called by one soldier, “The worst we had ever experienced in the war.”

Hargreaves writes, “For four hours, the bombers came, 4,500 of them. The first wave alone released 6,000 tons of explosives; two more waves followed. And then the artillery barrage—from land and sea, a quarter of a million rounds in all. The men in the front lines were buried. The bombs turned over the earth, filled in fox holes, covered weapons. Telephone lines were cut, radio trucks smashed, guns and panzers disappeared beneath piles of mud or were covered with soil. When the enemy attack came, they were not ready for battle.”

One panzer lieutenant reported, “Some of the 62-ton machines lay upside down in bomb craters thirty feet across. They had been spun through the air like playing cards. Two of my men committed suicide; they weren’t up to the psychological effect.”

At least 60,000 Germans, and probably many more, died trying to defend Normandy. However odious was the regime and cause they served, they fought bravely and, for the most part, honorably against overwhelmingly superior forces.

To read about the battle from the losing side’s perspective is a sobering and informative experience, one that should not be missed.

Short Bursts

Eisenhower, by John Wukovits, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2006, 204 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $21.95.

Eisenhower, by John Wukovits, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2006, 204 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $21.95.

For anyone wishing a concise biography of Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, John Wukovits’s new book is certain to fill the bill.

In the third installment of Palgrave’s Great Generals series, Wukovits explores Ike’s leadership strategies and his contributions to American warfare. Not only was Ike the architect of Operation Overlord (the Normandy invasion), but he was also the brains behind Operation Torch (the invasion of North Africa) and Operation Husky (the invasion of Sicily), struggling mightily to hold together a multinational coalition that was as difficult as trying to defeat a determined enemy.

Wukovits captures the essence of the man, a high-ranking general seemingly without ego. He writes, “Reflective of Eisenhower’s familial approach was his selection of living quarters in Great Britain. Within a week he had moved out of the exclusive Claridge Hotel, London’s most expensive establishment, for a simple three-room suite at the Dorchester Hotel. He then arranged for an unobtrusive home in the country, called Telegraph Cottage, to serve as a sanctuary in which he could escape the pressures of command. Located along a golf course, the retreat offered time for Eisenhower to read his Western novels, play bridge and golf, and recuperate from an exacting schedule.”

Eisenhower is a very personal look at one of America’s greatest generals and most beloved presidents.

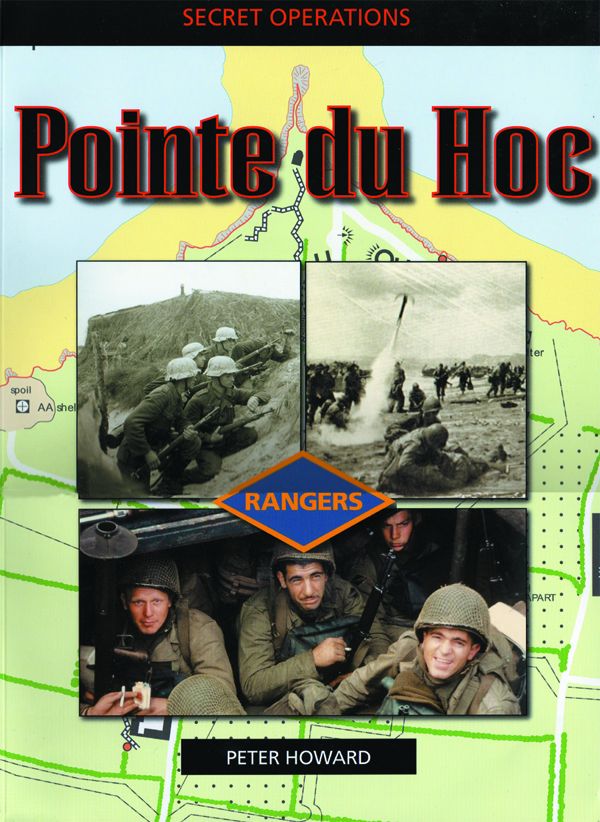

Pointe du Hoc (Secret Operations), by Peter Howard, Casemate, Barnsley, England, 2006, 96 pp., photographs, maps, $29.95.

Pointe du Hoc (Secret Operations), by Peter Howard, Casemate, Barnsley, England, 2006, 96 pp., photographs, maps, $29.95.

A large format (9×12), profusely illustrated book, Pointe du Hoc is an up-close look at one of Operation Overlord’s most daring and spectacular missions, the attack by 225 men of U.S. Ranger Force A, from the 2nd Ranger Battalion, up the sheer cliff to assault the German guns on top.

Following the Rangers from their early days, through training, then the audacious assault, Peter Howard gives the reader a comprehensive study of what many planners—and Rangers themselves—feared was a suicide mission. Knocking out the guns at Pointe du Hoc was of prime importance, for the Overlord planners worried that they could wreak havoc among the invasion fleet assembled off Utah and Omaha Beaches.

As it turned out, 135 Rangers were wounded or lost their lives in the mission only to discover that, prior to June 6, 1944, the Germans had removed the guns from their casemates and hauled them several kilometers to the rear. All the time, effort, and cost in human lives expended at Pointe du Hoc was for naught, making the operation tragic but no less heroic.

An index and bibliography would have made this superb book even better, but the great number of photographs, many never before published, make up for this deficiency.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments