By Bruce Weigle

Miniature wargames have been played by hobbyists for decades, both for pure entertainment and as part of legitimate research. Indeed, wargamers have long used well-known historical battles as a means to test their military acumen. Could you win at Waterloo where Napoleon failed? Can you lead the Army of Northern Virginia to victory at Gettysburg? Those are just two classic challenges that recall the earliest days of the hobby.

Inevitably, though, those types of classical challenges become a bit too familiar with repetition. So you are looking for a new military challenge. You want something historically familiar, but not very well known—something in which the quality of the troops and their weapons, their commanders’ mettle, and the historical details are unfamiliar to all but the most die-hard aficionados.

Which war might provide such a rich assortment of battles and a wide variety of military challenges?

Falling just about halfway between the end of the Napoleonic Wars and World War I were the Wars of German Unification. The largest of these was the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871. Because it was studied intensely by historians and military professionals up to and beyond World War I, it became one of the best documented European wars, giving birth to thousands of studies, histories, memoirs, and analyses. Fortunately, most of that historical material is still available, in English, for the discerning scenario designer.

I have published three sets miniatures rules covering the transitional wars involving the consolidation of the large European nation states such as Italy and Germany that occurred from 1859 to 1871. I will tentatively publish in the fall of 2015 a simplified set of fast-play rules known as “1871.” The fast-play rules are designed to give wargamers a way to accurately refight large, less well known battles of the Franco-Prussian War in a single sitting. The fast-play rules are an outgrowth of an earlier set of rules I published covering the Franco-Prussian War titled “1870.” I used a number of familiar conventions, as well as some new ones, to achieve my primary wargaming objectives, which are to enable a rapid pace, furnish a simple but accurate method of combat resolution, and adhere to historical authenticity.

The 11 scenarios selected (from both the Imperial and Republican periods of the war) needed to be well balanced, accurate, and challenging for the players and the designer. Because of its tactical possibilities and suitable obscurity, one key area of interest is the Battle of St. Quentin fought January 19, 1871. This was the Franco-Prussian War’s last major field battle, fought between General of Infantry August von Goeben’s First Army and General of Division Louis Faidherbe’s Army of the North.

As a game, it is fraught with possibilities. The armies were roughly the same size—each fielded approximately 25,000 infantry. Although the Prussians undoubtedly were of better quality, they fielded fewer battalions than the French, who also held an interior position, including some excellent defensive terrain.

It’s important, of course, to know the late-war situation to grasp the challenges of crafting the wargame rules. After six months of continuous warfare, France’s ability to continue fighting was nearly at an end. Virtually all of France’s professional army, which once was considered the best in Europe, was dead, incapacitated, or in Prussian prison camps. Hastily raised replacement armies kept the war alive in the provinces, but by January 1871 they had been defeated everywhere.

Paris had been under siege for three months and its citizens were on the verge of starvation. But the Third Republic was loath to admit defeat, even in extremis. One final effort was planned: a great breakout from Paris, with a supporting effort from the threadbare Army of the North. Both occurred on January 19 and both failed completely. As a result, the French government sued for peace a few days later.

Faidherbe’s role was to distract the Prussian First Army, which stood between the Army of the North and the Prussian lines of circumvallation around Paris, to prevent it from responding to the breakout attempt. Another objective was to compel the Prussian high command to dispatch reinforcements from Prussian King Wilhelm I’s army besieging Paris to Goeben.

Knowing that his small army, comprising four small divisions in two corps and two attached brigades, was incapable of actually defeating Goeben’s veterans, Faidherbe planned a surprise march around the Prussian right flank. He intended to accomplish this by crossing the Somme River at St. Quentin and severing the First Army’s vital rail line of communication near La Fere. When superior Prussian forces approached, he would slip away to the safety of one of his northern fortresses, specifically Cambrai, thus keeping his army intact.

Unfortunately for Faidherbe, Goeben became aware of the French maneuver in time. Gathering together as much of his army as he could (three incomplete divisions, as well as a few spare infantry and cavalry units), he shadowed the Army of the North’s march from the southern side of the river and nipped at its heels from the northern side.

The cold, rainy weather turned the fields to mud and contributed to the misery of both armies. By the time Faidherbe arrived at St. Quentin late on January 18, he knew that his plan had failed. His army was strung out, exhausted, and faced an enveloping attack from the west and the south. Due to a staff error, the 22nd Corps, his best troops, already had crossed the Somme, while the 23rd was frantically deploying west of the town against the expected Prussian attack the next day.

Faidherbe hoped to check the Prussian advance long enough to extract 22nd Corps back across St. Quentin’s solitary bridge and make good the whole army’s escape to its northern bases. Goeben ordered a converging attack on the town, intending to trap and eliminate the Army of the North once and for all.

Superficially, the French appear to have had several advantages. Although the Somme River split both armies, the French possessed the only nearby bridge at St. Quentin. Moreover, the open, sodden fields enabled the French infantrymen to dominate the battlefield with their superior Chassepot rifle. The Prussians’ excellent Krupp field guns were slow to arrive and slow to deploy in the muddy fields, while the less numerous (and less well served) French batteries were already largely in place on commanding terrain. But if the first-rate Prussian infantry could close with the less professional French troops, no one doubted what the outcome would be.

My first challenge was to factor in as many of the advantages and disadvantages each army possessed as possible to produce a historically balanced game. Next, I sought to make readers thoroughly familiar with their armies’ respective strengths and weaknesses. Contemporary accounts stressed that the Republican French armies were poorly managed.

With most of their professional officer and noncommissioned officer cadres long since removed from play, the composite, often ad-hoc formations of the French provincial armies were led by whatever talent they could locate. Former NCOs found themselves commissioned as company and even battalion commanders. Interestingly, former junior officers led battalions, and in at least two cases, they led divisions, while Faidherbe’s division and corps commanders had been field grade officers less than five months earlier. In addition, staff officers were completely untrained and in short supply, and cavalry was almost nonexistent. This was not a well-led army, although fortunately there were some leaders and many humble soldiers who more than rose to the occasion.

Faidherbe’s best troops were the second-string reservists, which included former soldiers and landed sailors, of his Marche regiments. Some had only a modicum of infantry training. About 60 percent of the rank and file, though, were half-trained guardsmen or barely trained conscripts. Their morale was shaky at best, and their combat effectiveness questionable. Goeben was quite aware of these shortcomings, declaring in his battle orders that his understrength 15th Division alone was “sufficient in number to fight with success the entire French Army of the North.” Many of the French units could not be trusted to advance when ordered, and were prone to panic. Their game morale grades reflect this, and in the game, as in reality, some flunked their morale dice rolls at the first test. Others, to the surprise of the Prussians (and play-testing wargamers), defied the odds and fought like champions throughout the day.

I gave the Prussian units, as befitted their historical performance, better morale ratings and favorable modifiers when in close combat, particularly against the lower grade French troops. To reflect their superior command control ability, the Prussians were allotted more command chits each turn, which allowed them about twice the agility of their clumsier French opponents.

French units, besides being saddled with lower morale ratings, depending on the professional proficiency of each type regiment, were also more heavily penalized if they lost a close combat or failed a morale roll. Historically, French commanders in several of the late war battles complained that their advances were often hindered by the crowds of fleeing soldiers from the units they had been sent to assist. Last, the 60 percent lower grade units—the Garde mobile and Garde nationale regiments—were prohibited from initiating close combat. This left only the regulars of the Marche battalions and the sailors capable of undertaking offensive action.

With an army like that, how could the Prussians fail to achieve victory by turn three? Goeben’s First Army, although superior in almost every respect, still had its share of difficulties to overcome. After two days of forced marches, it was as soaked and tired as were the French, and it would arrive on the battlefield piecemeal. Goeben, in his overconfidence, sent his only reserve formation, Colonel von Bocking’s battle group, across the Somme to help the 16th Division’s advance from the south. He also spread out his command even further in order to envelop St. Quentin from the north. Unfortunately, he had only a weak composite division and about seven squadrons of uhlans to do so. It was insufficient for the task.

The composite division, on the Prussian left, and the first brigade of the 15th Division arrived on-board in the late morning, and ejected the French from the towns and woods they had been defending. By early afternoon, when the game begins, the Prussians had regrouped and were ready to resume their advance. The 15th Division’s second brigade and the VIII Corps artillery had still not closed up. On the south side of the Somme, the first battalions of 16th Division to arrive were thrown directly into an assault against the numerically superior French troops of the 22nd Corps, which awaited them on the high ground beyond. Only after several setbacks, including a spirited French counterattack, would the 16th Division’s second brigade be committed to the frontal assault, together with six additional battalions from other units as they arrived.

The Prussians’ numerous cavalry units played only a minor role in this battle, being nearly useless for anything other than scouting and fighting other cavalry. Doggedly, the Prussians pressed forward, steadily pressing back the French everywhere until St. Quentin was entered almost simultaneously from the west and the south as darkness fell.

The battle was a Prussian victory. The Army of the North had taken grievous losses and was effectively hors-de-combat for the remaining nine days of the war. But it was not a complete victory. The bulk of the army survived, and therefore the First Army was compelled to remain in Picardy to keep an eye on it. With his forces arriving piecemeal, Goeben had opted to advance straight toward the spires of St. Quentin, instead of setting his sights on the real prize, the annihilation of Faidherbe’s tattered army.

The forces assigned to cut the Army of the North’s escape route north to Cambrai were insufficient. The sailors of Michelet’s brigade vigorously counterattacked these forces and checked their advance more than two kilometers short of the Cambrai road. The uhlans’ attempt to break through to the road was thrown back by an unexpectedly steady brigade of rifle-musket armed militia, who were surprised, according to one source, that their old “baguettes” could actually kill people. Thus, the majority of the Army of the North escaped, albeit in ruinous condition.

Using the original orders of battle from each side’s official histories, among other sources, and arrival times, the Battle of St. Quentin was play-tested five times by five mostly different teams of gamers on a 1:4000 scale terrain board representing about 65 square kilometers of the actual battlefield. The Prussian and French commanders’ mission orders were those of Goeben and Faidherbe. But, of course, as soon as the game began the players on each side could react according to the situation as they saw fit. The special modifiers worked very well, forcing each army to behave authentically. French commanders could neither depend on their orders being carried out expeditiously nor place much confidence in their troops’ staying power once engaged, especially as their casualties rose. The Prussians, with a paucity of infantry and late-arriving artillery, could not hope to prevail everywhere, nor could they afford the losses typically sustained by direct frontal assaults. They had the initiative, but would need a well-considered plan to do better than the First Army actually did.

Surprisingly, the Prussians only managed to eliminate the Army of the North once in the five games, and the winning strategy was grasped by a player who had participated in two previous games. One game was an aberration–a succession of bad die rolls and poor tactics stopped the Prussians far from the gates of St. Quentin. The other three games tracked the original battle very closely; the Prussians attacked the town instead of the neck of the sack into which the French army had placed itself. By the time the Prussians entered the city, the Army of the North, having resisted as well and as long as it could, was withdrawing unhindered off the board, which was exactly what happened in 1871.

Research for this battle was challenging. A reprinted, affordable History of the German General Staff 1657-1945 is available in English, but the French official history can only be partially accessed via Google Books. Several other detailed German and French histories exist, but they are difficult to access and a determined effort is required that entails access to a large library, assistance from a seller of rare books, or skilled Internet research. Most of them are contradictory, and for that reason, they must be constantly checked against other sources.

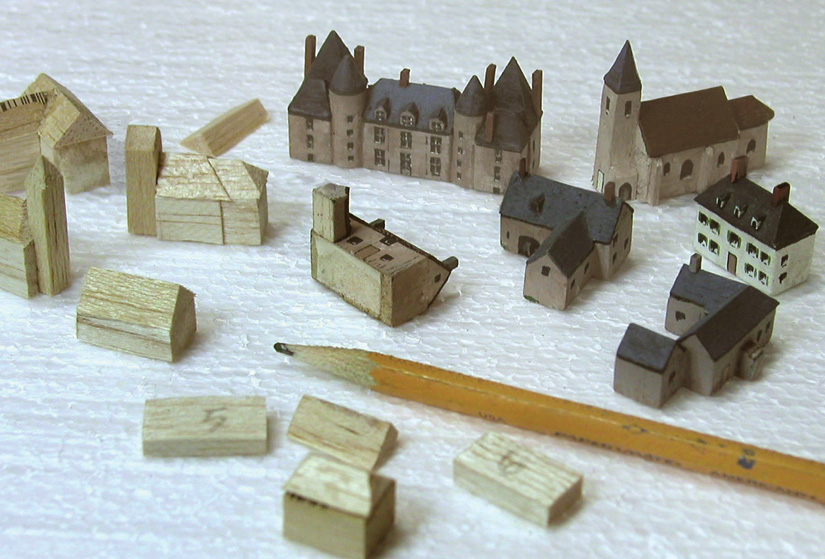

The cartography on which I based the terrain board for St. Quentin included a modern 1:50,000 scale topographical map and the excellent color map from the German official history. Using these sources, I sketched a map in Photoshop. I then constructed the board using carved Styrofoam and painted cloth. I built the 72-inch by 90-inch game board in six pieces so that it can be transported to different locations.

Since St. Quentin was a large battle, it was necessary to use figures of 6mm scale. The 6mm scale is frequently used in miniature wargaming to represent large battles in a small area. I chose to use 1,800 6mm figures (1,000 French and 800 Prussians) to portray infantry, artillery, cavalry, and commanders participating in the battle. I purchased the miniature figures from Heroics and Ros Ltd., of Reading, England. About 90 percent of these were painted by professional figure painters. Each stand represents an infantry battalion, a battery, or two squadrons of cavalry. They are placed on the board at their 1 pm positions for the eight-turn game. St. Quentin 1871 offers a satisfying alternative to the overplayed well-known battles with which most people are familiar.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments