by David H. Lippman

Just after midnight on February 9, 1945, across the diamond-shaped mass of forest, hills, and flooded terrain that defined the Reichswald, rain fell in a steady downpour upon a battlefield that had already seen some of the most ferocious fighting of World War II in Western Europe. British and Canadian artillerymen had delivered more than 8,000 tons of shells on the Germans, crushing their defenses and enabling the infantry to advance into the forest despite the mud created by rain and the flooding caused when German forces had opened sluice gates along the Rhine River. The first day of Operation Veritable had been a bloody success.

The following week would be even bloodier, and for the British and Canadian forces, victory would seem elusive at best, impossible at worst.

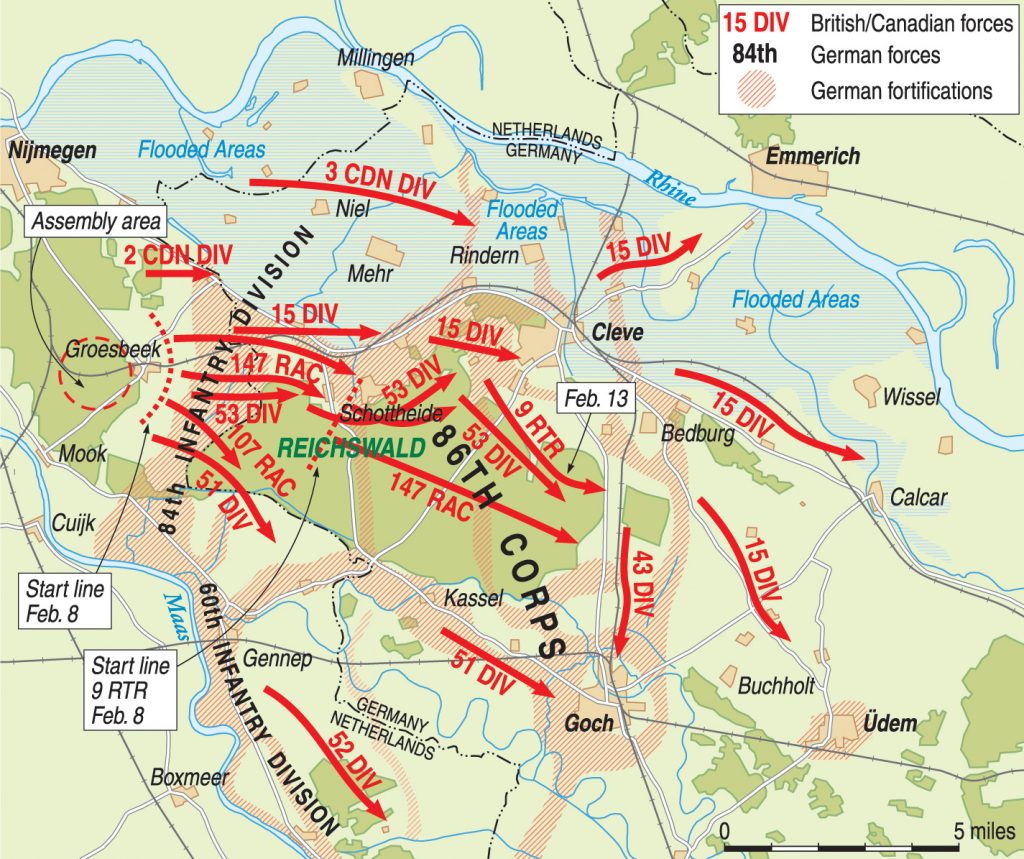

Veritable, one of the largest battles the British would fight in Europe during the war, was the brainchild of Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery. The plan called for five British and two Canadian divisions of XXX Corps, under Lt. Gen. Sir Brian Horrocks, part of General Sir Harry Crerar’s 1st Canadian Army, to attack the land gap between the Maas and Rhine Rivers from the German-Dutch border to the Rhine River. The Veritable drive was the northern hook of a giant pincer with the U.S. 9th Army, under Lt. Gen. William Simpson, as the southern hook, called Operation Grenade. Together, the two armies would meet at the Rhine, having caught 150,000 defending Germans in a huge net. From there, both armies would drive across the great river and into the Nazi heartland.

But before any of that could be accomplished, Horrocks’ men had to clean out the Reichswald. That would not be easy. Despite the massive losses the Germans had suffered in the Battle of the Bulge, they remained a formidable foe. The Reichswald was a forest with valleys, hills, and two major towns, Cleve—home of Henry VIII’s fourth wife, Anne of Cleves—and Goch. There was only one paved road from the Allied lines to Cleve. In addition to the natural defenses, the Germans had begun in 1938 creating a fortified line from the Reichswald to the Alsace called the “Westwall” by the Nazis and the “Siegfried Line” by the Allies, an impressive array of defenses and fortifications ranging from immense blockhouses to wooden “S-mines,” called “Bouncing Betties” by Tommies and GIs. When an unwary soldier stepped on one, it popped up to waist height and exploded, severely wounding the Briton or Yank.

These defenses, however, required troops. In the Reichswald, they were led by General der Fallschirmtruppen Alfred Schlemm, a veteran paratrooper, who commanded the 1st Parachute Army. Few of the German paratroopers were actually jump-trained. They were, however, highly skilled battlefield soldiers, possessing high morale and hard-won expertise in last-ditch stands.

Schlemm had other advantages. His men were equipped with many weapons that were superior to those in the British arsenal: the 88mm guns in the field positions; self-propelled armor; the world’s first disposable anti-tank weapon, the powerful Panzerfaust; and the MG42 medium machine gun, which could fire off an immense number of bullets at an astonishing rate, sounding like a buzzsaw. The MG42 had a major weakness, though: over-engineered, its metal tended to overheat and melt down.

Schlemm also added to his defensive positions; a fortified line between the flooded areas south of the Rhine and the Maas helped the German frontkämpfer (front-line troops) with a double series of trenches and anti-tank ditches. Behind that was the Westwall, which included defenses around Cleve and Goch. Behind that was yet another line, the Hochwald Layback, as a backup, with more trenches, wire belts, and mines.

The four-mile-wide Reichswald itself provided plenty of natural defenses: flooded land south of the Rhine, thick woods, narrow trails that went north to south—perpendicular to the planned advance—and most of all, soft soil, which would turn into mud under thaw and rain. Most of the woods were young pines four to seven feet apart. Along the northern flank and within its tree line, the Materborn Ridge ranged between 200 and 250 feet above sea level before pivoting in the northwest corner. There it created a 300-foot hill called the Branden Berg, which provided artillery spotters with a perfect box seat for the whole area.

But all this had very little impact on 1st Canadian Army and Veritable. The original plan had been to hit the Germans in December 1944, when the ground was frozen, making it possible to maneuver vehicles easily on the snow. But on December 16, Hitler disrupted those plans with his Ardennes Offensive, and XXX Corps was assigned to block the German offensive at the Meuse as a stop-line. After American troops blunted this blitzkrieg, XXX Corps joined the GIs in cleaning up the Bulge. The XXX Corps fought well but cautiously to avoid taking casualties in a force needed for Veritable.

After the Germans began their retreat, Horrocks’ troops headed back to their assembly areas between the Maas and Rhine, which had been held by the 2nd and 3rd Canadian Divisions during the Battle of the Bulge. It was one of the worst winters in European memory, and even the Canadians, used to harsh winters in Alberta and Saskatchewan, suffered.

Now Horrocks and Crerar prepared their plans and supplies for the massive assault. A total of 470,000 British and Canadian troops would assault the German defenses, ranging from Tommies in battle-dress to Canadian psychiatrists to deal with shell-shock.

This was the largest single offensive since the Normandy landings and breakout, and the British were determined to avoid the embarrassment of the Market-Garden fiasco in Holland in September, where the entire XXX Corps had been compelled to fight off of one road, called “Club Route.” Worse, this was a winter assault, creating special needs. Roads had to be repaired, strengthened, and maintained. A sudden thaw and heavy rain were turning the whole area into a giant morass.

When the battle started on February 8, a steady drizzle turned into pouring rain, but, backed by the heaviest British artillery barrage of the war, British and Canadian troops advanced steadily. They crushed six battalions of the German 84th Infantry Division, suffered almost no casualties from “shorts” (friendly artillery rounds accidentally targeted on one’s own troops), and took 1,115 prisoners for a loss of 349 Canadians and Britons. German dead totaled more than 3,000. Tommies found German telephone lines wrecked and gun positions mangled. Captured German officers told their interrogators that they could not give orders to their men. All the 84th could do was defend disjointed positions and penny-packets until their men died or surrendered. All the concrete works had been destroyed.

As the second day of the great offensive began, the normally ebullient Horrocks battled two difficult enemies: defiant Germans and a fever of 103 degrees, the continuing after-effects of lung wounds suffered in North Africa. Buoyed by the positive results of the first day and determined to maintain the pace of the offensive, Horrocks made what he would later describe in his own memoirs as one of his worst decisions of the war. He would send forward his major reserve force, the 43rd Wessex Division, at noon on February 9.

While the 43rd slogged east on roads rapidly turning to morasses, the battle raged on in forests whose trees had been turned into ghoulish wreckage and in towns reduced to rubble-strewn chaos, all surrounded by brown mud soaked in intense rain.

For the British and Canadian troops at the front, it was a miserable night, punctuated by artillery duels, the endless downpour of rain, the slogging struggle to move through mud, and the stench of death.

On the extreme right, the 51st Highland Division’s specialized armor worked throughout the night. Flail minesweeping tanks cleared a lane through German minefields that enabled an armored bridge to be placed in position. That, in turn, enabled support vehicles to bring the Scots the most important supply item of the day—500 tins of self-heating soup.

The 15th Scottish Division in the center was commanded by six-foot-nine-inch-tall Maj. Gen. Colin “Tiny” Barber. His height gave him an advantage in studying the forward battlefield, unlike his colleague, Maj. Gen. Ivor “Butch” Thomas, who was the size of a jockey.

Barber intended to send his reserve brigade, the 44th Lowland, with Grenadier Guards tank support (including deadly Crocodile flamethrowing tanks), through the front and across the German anti-tank ditches east of Frasselt, and then to assault the main Siegfried Line defenses while the two battered leading brigades took time to refuel, draw ammunition, and eat bully beef.

The 44th’s attack was intended to kick off at 9 PM on the 8th and to take Netterden by 1 AM. Once that was done, the other two brigades would resume attacking toward Cleve starting at dawn, the 43rd Wessex Division behind them.

But now the appalling weather had crushed Horrocks’ and Barber’s hopes. Rising flood water from the Rhine to the north and rain from above left XXX Corps almost immobile. The two leading 15th Scottish brigades had reached their objectives two and a half hours behind schedule.

Even so, the 44th trundled off in Kangaroo armored personnel carriers joined by grenadiers; mobile, small-box girder-bridge layers; and “fascine” tanks that could lay bundles to fill anti-tank ditches. The division had been assigned two routes of advance: the hard-surfaced road from Nijmegen to Cleve for the 227th Brigade, and a narrow track on the right for the 46th Brigade. But because of stiff German resistance, the main road could not be used, and now everything was jammed onto the muddy track—tanks, trucks, Bren carriers, jeeps, halftracks—in the rain and mud.

After seven hours of frustration, C Company of the 6th King’s Own Scottish Borderers (KOSBs), a company of flail tanks, and a collection of Grenadier Guards tanks reached the German anti-tank ditch. At 5 AM, 20 minutes before a murky dawn rose over the battlefield, 44th Brigade launched its attack. Lacking order, a senior Grenadier Guards officer yelled, “Advance!” and everybody did, just moving forward as quickly as they could.

Five flail tanks drove forward in five parallel columns, their whirling drums spinning, which enabled their hooks to slam against the ground, setting off anti-personnel mines, clearing a path for the infantry behind them. But three tanks bogged down in the mud. The two survivors advanced to the German anti-tank ditch. Armored Vehicle Royal Engineers (AVRE) fascine tanks moved in next and bridged the obstacle. The King’s Own Scottish Borderers pushed forward and seized two villages—Schottheide and Konigsheide—taking some badly shaken prisoners. Company C consolidated its position to await the rest of the battalion.

Captain Robert Woollcoombe later recollected: “It was one of the great moments of the campaign. We were the first British unit to breach the main belt of the Siegfried Line. The mist had cleared and the rain was holding off for a while. The sky was dull and overcast. Tactically it was mighty ground…various small hills, or knolls partly wooded stood about, the chief of which, named Hingstberg, was near Nuttenden, which gave its name to the whole sector.”

Once the entire KOSBs formed up, their commander, Lt. Col. Richardson, ordered A and B Companies to head east in their Kangaroos to Wolfsberg, where German troops were reported holding in position. Incredibly, the defenders had had enough. German NCOs led columns of men out to surrender. Medium gun positions were overrun, and a battalion headquarters and 10 officers surrendered to the KOSBs.

But the Germans were not idle. Schlemm saw that this was clearly a major offensive, and the defensive strategy was simple: hold on and counterattack. That would not be easy. The 84th Infantry Division was out of the game. General Johannes von Blaskowitz, commanding Army Group F, agreed to send in the tough but understrength 7th Parachute Division, but it arrived piecemeal. The 6th Parachute Division, in a similar condition, would follow, and then the 47th Panzer Corps under General der Panzertruppen Heinrich Freiherr von Luttwitz, an Olympic equestrian and veteran of two world wars.

Luttwitz put his corps, consisting of the 15th Panzergrenadier Division and 116th Panzer Division, on the road with orders to hold Cleve.

Meanwhile, the battle raged on. German troops, suffering from British shelling, also endured the miserable weather. Leutnant Hans Hueneborn of the 2nd Parachute Regiment led a 10-man reconnaissance patrol into the Reichswald.

“I was three days in the woods,” he said later. “My commander, a major, said I was to report to him in the cellar where he had his headquarters. I was just 50 meters from the house when I saw the British soldiers—there were many tanks. I shot three tanks with my Panzerfaust. I believe they were damaged. Then a grenade hit the trench where we were and I was wounded. We were in danger of being surrounded and captured. I called to my men, ‘Run and duck, run and duck! Get under cover in the cellar!’ and we got away. That night, I walked out of the forest and went to my parents’ house in Haversum.”

The 51st Highland Division, which planted its “HD” signs everywhere it went, continued its movement. The 2nd Seaforths of the 152nd Brigade suffered more than 100 casualties trying to clear the Kranenburg-Hekkens road in the heart of the forest. Two forward companies faced heavy German mortar and shellfire but fought their way across the main road. Major Ian Murray, the acting commander, chose boldness. “Profiting from the enemy’s concentration on our two forward companies, I pushed through my two reserve companies and they reached positions flanking the two forward companies on this road. We’d have been a rather thin red line had there been a counterattack. It was tough going. Fortunately the Camerons came through us with flame-throwing Crocodiles,” he said later.

The 5th Camerons faced tough going despite their flamethrowers. Lt. Ross Mesurier was attached to them with his scout platoon. “Without tank support which had become bogged down, machine-guns, snipers and mortars took their toll throughout the morning of the 9th,” he wrote. “My head was creased by a bullet, then a piece of shrapnel hit my back. Later on another fragment hit my upper left arm which stiffened up. The day dragged on, progress was slow and darkness came early. It also started to rain. Our company wireless operator was badly wounded in great pain, his uncontrollable moans seemed to draw gunfire. My company commander, Major Donald Callender, yelled out, ‘For God’s sake, Ross, do something.’ The wind was blowing toward the Germans, so I cocked a phosphorous grenade to throw it. It was hit by a bullet or a piece of shrapnel and burst in my face which was covered by blobs of burning goo. One lens of my glasses was covered. I rubbed handfuls of snow mixed with mud in my face to stop the burning. Some Germans began advancing towards us. Our firing forced them to go around. A few of us charged them firing from the hip. My Sten gun jammed so I used my shovel. They started to run and we chased them. I hit one with the shovel blade in the neck. He hit the ground in a heap. I swung at another but he ducked and it glanced off his shoulder. I was a little in front of my boys, so I decided to go back to my platoon,” he said later. Mesurier was evacuated to hospital.

Other 51st units also found hard going. A shortage of tracks and trails meant the division had to share routes with the 53rd Welsh, which led to traffic-control chaos. A Jock (51st Highlander) recalled, “Up this one route quantities of vehicles, gun, and men were sweating, swearing, and squabbling for priority rights. The Argylls wanted to come through on to their objective, the gunners wanted to come through and take up their positions for the morrow’s shooting program, the battalions of the Watch wanted to get up their food and greatcoats: nobody knew what the hell the Welsh wanted.”

Yet the 51st kept attacking. The division’s reserve 153rd Brigade was to clear the entire area between the Reichswald and the Canadians on their left, along the Maas River’s east bank. Major Martin Lindsay’s 1st Gordon Highlanders found ruts of mud two feet deep, forcing them to leave their amphibious Weasel troop carriers behind.

The Gordons reached the Mook-Gennep road by mid-afternoon. Lindsay ordered a series of artillery shoots ahead of the advancing infantry, which had the benefit of pummeling the defenders but the disadvantage of possibly killing the Gordons. But the Gordons kept to their tradition of “Strike Sure,” and C Company stormed through a deep valley and moved on the hamlet of De Hel, finding it was a well-defended German battalion headquarters.

“The Germans were all around us,” Company Sergeant-Major George Morrice said later. “I was able to get our company piper—Piper McLaughlin—into a trench and he played the pipes. It had a great effect on the Germans. We fixed bayonets and charged and were able to round them up. We captured an enormous number of prisoners at their headquarters. I caught the CO of the battalion and disarmed him myself.”

The battalion was then ordered to seize a strongpoint across the Mook-Gennep road that was holding up the 153rd’s advance. Lindsay himself led the attack. As the lead company moved forward, a platoon commander was wounded in the leg by a stick grenade. The men fought their way out and to the German entrenchment, a group of farmhouses surrounded by ditches and barbed wire. Lindsay ordered a two-minute blast of fire followed by a bayonet attack from the rear. In the first rush, six Germans were killed and many more taken prisoner.

“There was a cheer and a wild burst of Sten,” Lindsay said later, “and a wild surge forward, and in a moment a shout of ‘Kamerad’ and a column of Huns, 71 in number, came running out with their hands up…We went forward in the moonlight, climbing over broken walls and piles of rubble interlaced with a honeycomb of trenches. I was afraid some enthusiast in the (Canadian) front might shoot at us, so I passed the word back to the two pipers with Company HQ to play the regimental march, and before long we heard the distant strain of ‘Cock o’ the North’…(Then) heard the pipers of the Camerons of Canada and knew we had not far to go.” The sound of the Scottish pipes added to the German discomfort.

But disaster then befell Lindsay. As his men advanced, an explosion went off, and the company commander fell to the ground in pain, clutching his knee. The area they were advancing through was thoroughly mined. Lindsay froze, calling for engineers with mine-prodders to move in while still under fire. Canadian Camerons coming toward them did the same and began pulling mines out of the ground. Once done, Lindsay followed their precise steps for the link-up.

Other 153rd Brigade battalions had a rough day, too. The 5th Black Watch made a dawn assault across the Niers River and entered the village of Gennep, launching a two-day hand-to-hand battle. Maj. Alec Brodie led his company by walking down a street, carrying an open umbrella. Asked why he was doing so, he had a simple answer. It was raining.

Brodie’s contempt for danger and the Black Watch’s determination enabled the Scots to take Gennep, which in turn allowed Royal Canadian Engineers to build a 4,000-foot-long Bailey bridge across the Maas on February 20.

The Welshmen of the 53rd Division had a tough day as well, worsened by their traffic struggles with the 15th Scottish. The 160th Brigade pushed onto the northern edge of the Reichswald while the 158th Brigade, on their right, did the same, putting them 1,000 yards from the main German defense of the Materborn ridge, a hilly area that was the key to the defense of Cleve. The Germans had reinforced it with the tough men of the 6th Parachute Division, who attacked the 4th Welch several times. The Welch beat them off, and the Germans lost six guns, but the 158th Brigade had lost the initiative.

The 53rd Division also lost most of the roads in its rear, which collapsed in the pouring rain and mud and had to be closed. Royal Engineers and working parties spent the day trying to create hard surface. Sherman tanks, with their narrow track width, easily bogged down.

To the north, the two Canadian divisions were struggling with both the Germans and the flooded terrain. The 2nd Canadian Division was pinched out of the battle and could only be a spectator until the next round, leaving fighting to the 3rd Canadian Division.

The Germans had blown dikes in the Rhine River, which turned the low-lying land into a vast swamp. At dawn on February 9, the 8th Brigade’s North Shore Regiment mounted their Buffalo amphibious armored-transport vehicles and drove through the water to Kekerdom, clearing three factories. They had lost one officer and nine other ranks (enlisted men in U.S. parlance) killed, another officer and 12 other ranks wounded, and captured 95 Germans.

The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada passed through them and met no opposition in the rising water, capturing 11 lost German soldiers and freeing two trapped civilians.

Meanwhile, 8th Brigade was facing a major defense point called “Little Tobruk,” which consisted of a blockhouse, a concrete pillbox, and field defenses all surrounded by dugouts and barbed wire. The 1st Canadian Scottish (Can Scots) got the job, but they had to advance across the narrow Querdamm over flooded ground, making the advance difficult. Even so, they overran several dugouts and sent back 23 POWs. Now they faced the blockhouse, and Lt. W.G. MacIntosh ordered his No. 10 Platoon to advance. German MG42s opened fire with their distinctive buzzsaw sound to deadly effect, wounding several men and killing Lance Cpl. Edwin Fiddick and Cpl. Arthur Sidney Low. Private Mayeso Mayes tried to rescue Low and was cut down himself.

The company’s PIAT (antitank) team took aim at the bunker, but their shells only scratched the concrete. MacIntosh realized he could not take the bunker from the front and called on 11 Platoon to get its Buffaloes to the edge of the dam near his company HQ. MacIntosh wanted them to turn a Buffalo into a floating bunker-buster. He loaded Sergeant L.A. Cummings and five men from 12 Platoon aboard, armed with Bren medium machine guns and a PIAT. The Buffalo was equipped with 20mm and 50mm guns. While the Canadians loaded up the Buffalo, No. 10 Platoon cleared a house to the pillbox’s right, capturing five Germans and eliminating a machine gun.

Now Cummings’ Buffalo made a wide circle in the dark and drove down on Little Tobruk from the left and rear, opening fire with everything it had. As they did, No. 10 Platoon leaped up and attacked the pillbox. Caught in the vise, Little Tobruk was doomed, but not without the loss of Private George Robertson, a platoon old-timer.

The assault had taken all day, and B Company moved on, with No. 12 Platoon clearing out Little Tobruk’s defenders. Twenty-four-year-old Sergeant David Janicki of Vernon, British Columbia, one of the platoon’s few D-Day veterans, led his section up the length of the dam and broke into the battered blockhouse, capturing three officers and 61 soldiers while killing a good number more. While Janicki sorted out the prisoners, a German sniper shot him dead.

Major Earl English, commanding B Company and overseeing the final operation, studied the new prisoners and found one of the captured captains was very nervous. English ordered his men out of Little Tobruk and down a dam embankment. Moments later, German shells blasted the pillbox. One of the last German radio messages out of it before surrender had been to announce that fact and to request a bombardment on the position to kill the incoming Canadians. English’s alertness had saved his men—and the POWs.

The Can Scots had more work to do. Their attack had begun in the dark with Buffaloes taking the troops into battle, each carrying 20 men. The Buffaloes battled ground obstacles—underwater fences, shrubs, and terrain that would jam the vehicles’ tracks and spin them around, putting them off course.

The strange flotilla finally hit terra firma too far to the right on a road running into the tiny village of Germenseel, a mile and a half south of Niel. A Company’s Captain Joseph Andrews and D Company’s Major Dave Pugh convened to figure out where they were and what to do. Andrews hopped back on a Buffalo and probed the village from the north while Pugh sent a patrol along the raised road to enter it directly. Andrews found an anti-tank ditch ahead of him, and his maps showed he was at Germenseel—they were attacking the wrong village. Worse, they couldn’t report the mishap to the Can Scots’ commander, Lt. Col. Desmond Crofton, as their radios weren’t working.

Meanwhile, Crofton wasted no time. He loaded up his HQ team on two Buffaloes to find out what was going on and reached Niel, where they came under Panzerfaust fire. A German rocket hit the lead Buffalo, setting it ablaze, killing its British driver and Can Scot Privates Bernard Merlyn Krislock and Max Bradie Brown. Crofton suffered a bad compound fracture himself. The following Buffalo tried to assist the men in the leader but was turned back by heavy fire. Crofton and his injured colleagues crawled into a nearby barn and took cover, waiting 12 hours for assistance.

Meanwhile, Corporals R.G. Allen and O. Quesseth swam, waded, and crawled past the buildings to a road covered in three feet of water. From there they waded back to the battalion’s CP and reported to Maj. Larry Henderson, who would now have to take over the battalion in Crofton’s wounding and absence. He sent an amphibious Weasel to rescue the HQ’s wounded.

However, A Company and D Company maintained their attack on Niel in the cold, hard rain and dense cloud cover. A Company moved in from the southwest and D Company from the northwest; their junction point was the church. More than 100 Germans defended Niel but were in no mood to hold the flooded town, and they quickly surrendered. A few diehards fought on until 7 AM, when A Company raised its battle flag on top of a building to honor its first successful action on German soil.

The two company commanders repaired to the church to make dispositions, and as they talked, German artillery near Cleve hurled shells at them. A Company’s leadership went unscathed; Pugh and his runner fell gravely wounded, and Pugh’s acting second-in-command, Lieutenant Donald Neville Fergusson, and Private Eric Sekov Hansen were killed. That was the only bombardment Niel suffered; Buffaloes then rumbled in to haul off the wounded and POWs. The remaining Can Scots soon realized that the town they had taken was being flooded.

The Can Scots climbed into higher stories of the village’s buildings and watched the water swirl past them below. Their job now was to hold on while the Royal Winnipeg Rifles clattered by in their Buffaloes for the attack’s next stage. The Can Scots had lost one officer and seven other ranks killed, three officers and 14 men wounded, and one missing.

As February 9 closed on the Reichswald, the rain kept pouring. The British advance was slowed by mud, traffic jams, and German resistance, but Horrocks could count on several gains—the 15th Scottish Division was moving on Cleve, 2,700 German POWs in shabby mud-covered uniforms were shuffling into “the bag,” the guts of the Reichswald forest had been cleared, and the first-phase advance line—a reverse letter “L” from Gennep to Asperden to Cleve—was taken.

The next day, reinforced by the 43rd Wessex, Horrocks’ men were to crack the main Siegfried Line. On the right, the 51st Highland Division would clear Gennep and Hekkens in preparation for the attack on Goch, Udem, and Weeze. The 53rd Welsh would drive on the Cleve-Goch road. The 43rd Wessex would finally pass through the 15th Scottish, wheel right, and capture Goch. The 15th Scottish would clear Cleve and move on Emmerich and Calcar. Most importantly, the southern half of the great pincer, Operation Grenade, would open on the 1st Canadian Army’s right, tying down the Germans.

Crerar’s intelligence summary forecast the German reactions thusly: “If he has forces available either from the Hochwald (a smaller forest east of Cleve) or from across the Rhine he will be tempted to regain Cleve or at least seal it off. If he cannot do so, then he must hold Goch and also cover the nearest Rhine crossings.”

But on the 9th, the US 1st Army, under Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges—south of the 9th Army—attacked toward the massive Schammeneauel Dams, which held back millions of gallons of water from the Roer River. The 9th Army was to attack across the Roer on the 10th. The Americans intended to seize the dam before the Germans could blast it open and set off a torrential flood on the Roer that would drown the 9th Army’s offensive. The Germans didn’t blast the dam open; instead, they released the sluice-outlet gates that held its reservoir, which set off a gradual flood of 100 million tons of water down the Roer, heading north, raising the river by five feet. This would make it impossible for the Americans to throw pontoon bridges over the Roer.

Montgomery went to Simpson’s HQ to review the floods, situation, and maps, and agreed with Simpson that the Americans would have to postpone the assault by a minimum of 11 days. The Germans would thus be able to send in reserves to stop Horrocks’ attack.

The Americans released two of their own divisions to the British sector, which in turn enabled Montgomery to assign two more divisions to XXX Corps, the 52nd Lowland Division and the 11th “Black Bull” Armored Division.

So as the rain fell, mud deepened, floods worsened, and troops became exhausted, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander, penned a realistic assessment of the situation to the Combined Chiefs of Staff in Washington, describing the battle as a “bitter slugging match in which the enemy had to be forced back yard by yard.”

February 10 called for the 53rd Welsh, like all British divisions, to continue their attacks, but communications were a complete mess. The main divisional axis was closed to all vehicles but top-priority traffic. Every man available was ordered to create road surfaces, and the combatant men restricted themselves to patrolling.

That day, the 15th Scottish, 43rd Wessex, and the 9th Armored Brigade finally took Cleve. The 43rd Wessex had a fine combat record under Thomas. They had spent the years from 1939 to 1944 training hard under difficult conditions so that combat would seem easy in comparison. Many believed the Wessex men were the most “over-exercised” division in the British Army, but when put to the test, they hammered the Germans in Normandy, Falaise, and all the way to the Dutch border, suffering 10,000 casualties.

The 129th Brigade attacked first, with the 4th Wiltshire (Wilts) riding into action on the tanks of the Nottinghamshire Yeomanry (known as the Sherwood Rangers) amid icy rain and heavy mud, moving in fits and starts, delayed by massive bomb craters left by the RAF Bomber Command’s savaging of Cleve the night before the assault.

The 4th Wilts grabbed 75 POWs quickly, but then a Sherman tank appeared from the east. This turned out to be a “Trojan Horse”—a captured tank in German colors leading an enemy assault force. The Wilts opened fire and stopped the attack.

The fighting was ferocious. Even 129th Brigade HQ was caught in the battle, which raged in the town’s buildings as well as the Siegfried Line’s emplacements. Twenty-nine Germans were found dead in the Brigade HQ’s back garden. When two Germans broke away to surrender, their comrades shot them dead.

The 94th Field Regiment’s gunners, following the infantry attack, set up shop in the Siegfried Line using its trenches and dugouts. They were impressed at how deeply they were constructed, including electric lights and bunks.

Sydney Jary of 4th Wilts plodded past 15th Scottish men and noted how they were “strangely silent.” In a short time, they were facing a Mark V Panther tank, and Private Tipple hit it with his PIAT. The wounded tank shuffled away, but German paratroopers in their mottled uniforms engaged the 4th Wilts with their MG42s from positions in the rubble.

In another artillery duel, Sergeant Les “Bozzy” Bosworth and his entire anti-tank gun’s crew were killed when a German shell hit their ammo supply. Bosworth’s death greatly upset his comrade, Corporal Doug Proctor, as the pair had played piano duets to entertain their buddies.

In the fighting, an officer and 20 gunners of the 29th Anti-Tank Regiment cornered and captured a German officer and 78 men.

The 129th Brigade’s commander, Brigadier Hubert Essame, a veteran of World War I and Dunkirk, said that February 10 was distinguished “by a traffic jam of huge and bewildering proportions.” All communications with Essame’s brigade were totally broken down, and vehicles, tanks, and guns of the 15th Scottish and 43rd Wessex were intermingled in the mud and flooding.

The two divisions battled in Cleve amongst ruins and bomb craters. Isolated groups of Wessex men regularly faced being overrun by German paratroopers but held on, fending off the attacks.

Despite the chaos, Thomas pushed his 214th Brigade forward, the 5th Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry (5th DCLI) and the divisional-reconnaissance regiment leading the way down a white sand track and into open ground east of a forest near the Materborn feature. German troops opened fire, knocking out some British vehicles while others bogged down in the mud. The 5th DCLI got to work, storming the small village ahead at dusk. Thomas’s third outfit, the 130th Brigade, could not advance at all.

The whole 43rd Division was supposed to be clear of Cleve. Instead it was held in place by massive traffic jams, cratered terrain, mud, and German defenses. This situation made the 15th Scottish’s task almost impossible. The division and its supporting specialized armor were to move up a road jammed by the 214th Brigade’s vehicles. Unit commanders got into arguments over which unit had priority.

But the British kept trying despite the chaos. The Royal Scots Fusiliers cleared the bare top of the Cleveberg hill, a mile and a half from Cleve’s center. Seeing troops on the feature, 43rd division guns treated it to a bombardment, resulting in casualties from friendly fire. It was clear the two divisions would have to spend February 10th regrouping before pushing on.

To the south, the 51st Highland Division on the right flank maintained its attack. The 2nd Seaforths had to take their usual objective, a well-defended strongpoint on the Siegfried Line. This one consisted of three large pillboxes made of four-inch steel and two-foot concrete, packed with mines and trip wires. The 2nd Seaforths attacked with what was now becoming their usual method, using smoke to blind pillboxes followed by high-explosive shells directly into the embrasures. After that, an AVRE Petard—a tank whose main weapon was a giant mortar—would fire its “dustbin” shell at the embrasure, blasting open a hole. The flamethrowing Crocodiles would then burn out the defenders. Through this grim and somewhat time-consuming method, the 2nd Seaforths accomplished the task. The 5th Seaforth was less lucky; they met heavy defensive fire, but eventually took 35 prisoners.

After that, the 152nd Brigade drove on Hekkens, intending to take the village and wheel right. Instead, the whole brigade was pinned down in a ditch just 50 yards from the German positions. The 154th Brigade moved up through the muck to add power to the assault. In the evening, the 153rd Brigade loaded two battalions into assault boats to cross the River Niers, now swollen 100 feet wide by the Roer Dam spill, and the 5th Black Watch gained the dubious honor of finally taking Hekkens.

On February 11, the German reserves—47th Panzer Corps with its two divisions, the 15th Panzergrenadiers on the left and 116th Panzer on the right—headed north, arriving in their assembly area that evening. Neither division was as tough as it had been earlier in the war, having been worn down by the Battle of the Bulge; the entire corps mustered only 50 tanks. But it still had plenty of other armored vehicles and veteran troops, and the tanks were superior to their British opponents.

Two British and one Canadian division resumed the offensive on February 11. To the north, the 3rd Canadian took the town of Duffel before dawn and headed east, mopping up German resistance by early evening along the Spoy Canal.

The 15th Scottish and 43rd Wessex Divisions had spent a day struggling to sort out their administrative issues, and now moved to sort out the Germans. The 15th Scottish hurled a two-pronged attack on Cleve, with the 227th Brigade and Scots Guards tanks on the left and 44th Brigade and Grenadier Guards tanks on the right. The Germans counterattacked against 44th Brigade but failed; the 44th took 180 POWs. These steps allowed some of the exhausted frontline Tommies of the 43rd Division who were fighting in Cleve to stand down and get their first hot meals and real sleep in more than 50 hours.

The 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers led the 44th into Cleve, defeating German Panzerfaust teams as they advanced. The fighting for the ruined town went on all day. Scottish troops wrecked Cleve, creating or finding what the 4th Wiltshires historian described: “There were bomb craters and fallen trees everywhere, bomb craters packed so tight that the debris from one was piled against the rim of the next in a pathetic heap of rubble, roofs, and radiators. There was not an undamaged house anywhere, piles of smashed furniture, clothing, children’s books and toys, old photographs and bottled fruit, were spilled in hopeless confusion from the sagging crazy skeletons of houses.”

Neither the men of the 15th nor the 43rd were particularly bothered by wrecking Cleve. Captain Woollcombe wrote: “So our first night in Germany came down in utter destruction and the crackling of fires. It is hard to reflect the violence of it. Always there was one more river, and during the opening days of the Veritable offensive, a wave of bitterness swept through the streets as never before. At last it was Germany. The thought never left you: Germany. It did not matter what damage we did.”

The 43rd Division’s 214th Brigade ordered a set-piece attack to finally overwhelm the Materborn Ridge, doing so with a heavy artillery barrage followed by a tank-infantry attack by 5th DCLI and 4th/7th Dragoon Guards. The massed assault demolished the German position, but the surviving paratroopers showed their usual enthusiasm for last-ditch stands, and did so in the face of the 7th Somerset Light Infantry (“Sets”), which stormed Materborn under fire from German self-propelled guns, houses crammed with infantry, and heavy sleet.

Private Len Stokes of the Sets described the day’s work: “We had spent the whole night on the tanks; it was bitterly cold, icy rain, and driving sleet. I could not find any footholds and could only just manage to hold on with my fingers. We could not sleep for fear of falling under the following tank. Breakfast consisted of one tin of self-brewing soup divided between two men. I shared with the Company Sergeant Major. My hands and arms were useless, must have been in the last stages of frostbite. The CSM fed me. Later orders were given for the Somersets to cross the start line at 1600 hours to attack along the Goch road and capture the village of Hau. Delay because the crossroads were being shelled. The road was straight for hundreds of yards. Everyone was by now exhausted in the cold, wet, and sleet, and very dark between farms. B Company got into the cellar of a house where we reached our first objective, a farm at 0430 hours following two nights on the road and 13 hours of night fighting without sleep. During the rest of the night and all the next day, 12 February, we were heavily shelled and mortared.”

The day’s final objective, Hau, was still another half-mile away, but the Sets pressed on, tanks unable to follow. For five hours they struggled to push down the road. By midnight all ranks were exhausted, and the commander tried one last shot—a drive straight down the Goch road to a bend south of Hau. Hand-to-hand fighting went on all night.

The 5th Seaforths, pinned down all day on the 11th, now tried to break the German defenses in Hekkens, which consisted of an anti-tank ditch and the usual array of mortars and machine guns, the latter firing at stomach level. Mortar shells exploded in trees. The only cover was a narrow road ditch; men had to lie three deep to avoid being shot. They could hear German paratrooper NCOs giving orders to their men.

Lieutenant Colonel John Sym, the 5th Seaforth’s CO, was hit in the neck by a rifle grenade but refused to evacuate. He called for tank support but was told it wouldn’t reach him until the morning of the 12th. Meanwhile, stretcher bearers risked their lives to carry wounded men back through the mud.

When the tanks arrived, a German 88mm anti-tank gun opened fire, forcing them back. At noon, the exhausted Sym collapsed, and the 5th Seaforths were ordered to withdraw, covered by the surviving tanks. They had suffered 94 casualties.

Having battered the Seaforths, the Germans prepared to withdraw, but the Black Watch surprised them with a charge on Hekkens, backed by artillery. The Germans were stunned by the violence of the barrage and the Scots. Without any British casualties, more than 300 Germans surrendered. Major Landale Rollo interrogated a German officer soon afterward. “He told me, ‘If you had been 10 minutes later, you wouldn’t have got us.’ But we were so close behind the bombardment that we were still all in the cellars. We got in just as it lifted. Another few minutes and they would have got away.”

That evening, Montgomery signaled to the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke: “Enemy resistance against ‘Veritable’ is becoming greater and the operation is drawing up north most of the immediately available reserves…We have made steady progress. We now hold the road center of Cleve securely and own the whole of the Reichswald Forest and have pushed the enemy well south of Gennep at which place we are building a Class 40 bridge which will be ready for use on Thursday morning. Our prisoners now total 5,000 and our casualties total 1,100.”

It was steady progress, but unbelievably slow. The flooding of the Roer dams, the German reinforcements, and the unceasing rain were turning a blitzkrieg into a crawl. The battle was far from over.

Author David Lippman resides in New Jersey and writes frequently on a variety of topics for WWII History.