By Patrick. J. Chaisson

Admiral Soemu Toyoda needed answers. The newly appointed commander in chief of Japan’s Combined Fleet, Toyoda found himself facing several unpleasant facts. By May 1944, Allied naval and air strength in the Pacific Ocean was growing at an alarming rate. Already, fast-moving enemy forces had advanced far across northern New Guinea and into the Admiralties and through the Marshall Islands in the Central Pacific.

Toyoda could not yet determine whether the next American thrust would head north into the Marianas or continue west toward Palau and the Philippines. The six carriers, 10 battleships, and 40 other warships of his First Mobile Fleet could crush an enemy advance, but those vessels carried only enough fuel for one decisive sea campaign. Before sending Japan’s last remaining surface force into battle, Toyoda required hard evidence of American naval activity and intentions.

Much had changed since the heady days of 1941 and early 1942. Japanese long-range patrol aircraft, once able to roam far into Allied territory, could now only rarely penetrate the enemy’s air defense umbrella. Radio interception, so useful during the war’s first months, was rendered virtually useless by advanced American communications security procedures. That left submarines as Toyoda’s sole reliable means of reconnaissance.

Unfortunately, Japan’s largest, most capable fleet subs—the oceangoing I-class boats—were increasingly being pressed into service as transports hauling food and supplies to Imperial Japanese Army garrisons marooned by leapfrogging Allied forces. Scouting duties would have to be performed by the smaller Ro-class submersibles of Rear Admiral Noboru Owada’s Submarine Squadron Seven. These vessels were designed for coastal patrol, however, and lacked the surface radar systems Owada deemed so necessary for conducting reconnaissance missions.

What their crews did not lack was courage. Each Ro-class boat then anchored at Saipan in the Marianas held between 40 and 60 sailors, the cream of the Imperial Japanese Navy undersea force. Combat veterans all, these well-trained seamen posed a substantial threat to any Allied vessel caught in their periscope sights.

Yet Owada’s orders were to locate and report enemy warships not sink them. He directed his boats to picket a 200-mile track between New Guinea and the Caroline Islands labeled the NA Line. Should they spot an Allied armada steaming toward the Philippines, these scouts were sure to radio back with positive confirmation. Armed with this intelligence, Admiral Toyoda could then order his Combined Fleet into the climactic battle he believed would win victory for Japan.

On May 15, 1944, the seven Ro-class boats of Submarine Squadron Seven departed Saipan to take up stations along the NA Line. Their 650-mile voyage would take six days and was tracked closely both by Owada’s staff on Saipan and Combined Fleet headquarters in Japan.

The progress of Squadron Seven was followed by another group of naval officers, listening from a heavily guarded facility at the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. These men belonged to Fleet Radio Unit-Pacific (FRUPac), the top-secret signal intelligence center responsible for collecting and decoding all enemy radio communications intercepted by the U.S. Navy. Already FRUPac had helped win a stunning American victory at Midway, not to mention its role in Operation Vengeance, the ambush of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto by U.S. Army Air Forces Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters in 1943. This brilliant team of mathematicians, puzzle solvers, Japanese linguists, and electronics experts was about to change history once again.

A routine radio transmission, made on May 13, 1944, set in motion what would become one of the most epic battles in the annals of antisubmarine warfare. This short, encrypted message came from Lt. Cmdr. Yoshitaka Takeuchi, captain of the fleet sub I-16. Takeuchi’s report, plucked from the airwaves by American technicians, advised Admiral Owada that his vessel was due to arrive with food and supplies for the bypassed garrison at Buin on the southwest tip of the island of Bougainville on May 20.

FRUPac analysts deciphered enough of Takeuchi’s dispatch to estimate his course and time of arrival at Buin. This information quickly made its way to Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey’s Third Fleet headquarters, also at Pearl Harbor, for action. Halsey had to move fast, though, since intelligence such as this was extremely perishable. Countless factors from weather to mechanical breakdowns to unpredictable sea conditions might put I-16 miles from where the Americans thought it was. And just because FRUPac knew the whereabouts of an enemy sub did not mean the U.S. Navy could get hunter-killer teams there quickly enough to find and sink it.

Fortunately for the Allies, a small group of destroyer escorts (DEs), purpose-built to attack submarines, was then awaiting orders at Purvis Bay off Florida Island in the lower Solomons. The group, designated Escort Division 39, consisted of USS England (DE-635), USS George (DE-697), and USS Raby (DE-698), all newly commissioned Buckley-class vessels on their first war cruise. Kept busy thus far with routine convoy escort duties, few sailors aboard these three DEs had yet seen combat.

A series of events would rapidly transform them into seasoned veterans. On May 18, a communiqué from Third Fleet arrived directing Escort Division 39 to intercept a “Japanese sub believed heading to supply beleaguered forces at Buin.” After posting its estimated location, the electrifying message concluded: “He is believed to be approaching this point from the north and should arrive in that area by about 1400 [hours] 20 May. Good hunting.”

Each of the three DEs in Escort Division 39 measured 306 feet in length with a beam of 36 feet. Fully combat loaded, a Buckley-class destroyer escort displaced 1,740 tons. Two General Electric turbo-electric engines drove the vessel to a top speed of 24 knots, while maximum cruising range exceeded 5,000 miles. A ship’s company typically included 15 officers and 198 enlisted men.

A suite of electronic sensors assisted the crew in its mission of locating enemy targets. SL search radar helped find surface vessels, while SA “bedspring” radar identified possible aerial threats. But the DE’s primary detection system was QSL-1 sonar, which sent a pulse of high-intensity sound called a “ping” into the water. Echoes reflected off such solid objects as a submarine returned to the ship, where trained sound operators could then determine the contact’s range and bearing.

The destroyer escort also packed a lethal punch. Apart from 20mm Oerlikon and quad-mounted 1.1-inch antiaircraft cannons, each Buckley-class DE came equipped with three Mk 22 3-inch/50-caliber deck guns—two forward and one aft. Three 21-inch torpedoes in a triple tube launcher mounted atop the superstructure deck were intended for surface vessels, while a battery of depth charge projectors on the ship’s fantail could devastate plunging submarines with a string of “ashcans” each containing up to 600 pounds of high-explosive filler.

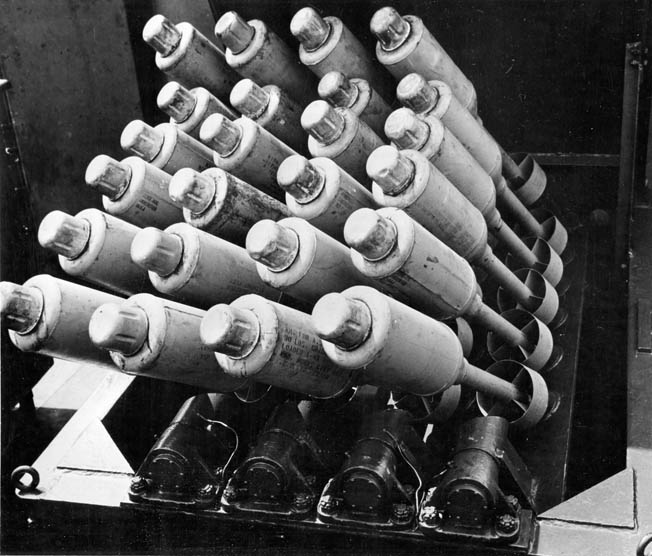

Just entering service in the Pacific that spring was a new and deadly weapon, the Mk 10 “Hedgehog” forward-firing spigot mortar. The DEs of Escort Division 39 all carried this British-designed projector, which fired a salvo of two dozen 24-pound contact-fused charges intended to fall in a circular pattern up to 270 yards ahead of the ship. Hedgehog rounds could be aimed to fall slightly right or left of center line and would only explode if they struck a submarine. By 1944, Japanese submarine captains had learned how to evade blindly dropped depth charges; Hedgehog-equipped destroyer escorts could now track a target on sonar throughout their attack and thus greatly increase the chance of a precision kill.

Sub hunting was a complicated, intricate task that required every officer, NCO, and bluejacket—from soundmen to Hedgehog gunners to the engine room gang—to work together as a team. Even the newest hands in Escort Division 39 knew their only chance to defeat the foe was through relentless training, and aboard one of those DEs training had become an obsession.

Since its commissioning in December 1943, the USS England, named for Ensign John Charles England, killed at Pearl Harbor, had earned the reputation of being a “taut ship.” Her crewmen devoted themselves to achieving excellence in equipment maintenance, ship handling and, above all, proficiency with the vessel’s weapons systems. They knew theirs was a kill-or-be-killed profession; coming in second against a Japanese submarine meant violent death on the lonely ocean.

Leading the England’s company to excellence was an unlikely taskmaster. Lieutenant John A. Williamson, a 26-year-old from Birmingham, Alabama, served as the ship’s executive officer (XO). Taking a reserve officer’s commission in 1940, Williamson soon found himself aboard the destroyer USS Livermore in the North Atlantic. Although the United States was then technically not at war, fully armed American warships on the “Neutrality Patrol” regularly shepherded convoys to and from Great Britain during the height of the U-boat peril. During his nine months of escort work, Williamson often witnessed firsthand the horrific toll that German subs were taking on Allied merchantmen.

Lieutenant Williamson next served as an instructor at the Subchaser School in Miami, where he helped train the Navy’s next generation of sonar operators. He then skippered a wooden-hulled patrol craft along the East Coast before receiving orders to join England for duty in Pacific waters. As XO, Williamson brought to his new ship a remarkable combination of battle experience, technical knowledge, and passion for excellence.

The England’s captain, Lt. Cmdr. Walton B. Pendleton, was a middle-aged career Navy officer who practiced an unusual hands-off style of command. Recognizing his executive officer’s leadership talents, Pendleton wisely gave few orders while allowing Williamson the freedom to prepare England for wartime service. The combination worked; months of incessant drills had made her crew supremely confident, even cocky. Lieutenant Williamson and the few other veterans on board knew, however, that combat would prove to be the ultimate test for this little warship and her spirited crew.

Shortly before dusk on May 18, 1944, the three DEs of Escort Division 39 set out to find and sink I-16. Along with Lt. Cmdr. Pendleton aboard England, Lt. Cmdr. Fred H. Just commanded George, while Lt. Cmdr. James Scott II skippered Raby. Commander Hamilton Hains, acting as Officer in Tactical Command, controlled division operations aboard George.

By noon the next day, England, George, and Raby were northwest of Bougainville, steaming in a line 4,000 yards apart with sonars actively sweeping the ocean. At 1325 hours the England’s junior soundman, Roger Bernhardt, suddenly reported, “Contact!” In disbelief, the officer of the deck concluded that Bernhardt must instead have heard some fish—I-16 was supposed to be miles away.

But the young sonar operator stood his ground. “Echoes sharp and clear, sir,” Bernhardt replied. “Sound is good!” With that, the crew of the England sprung into their well-practiced action drill, only this time it was for real. Pendleton and Williamson made for the bridge while all over the ship crewmen rigged for battle.

George and Raby stood by while England pursued the target. A dry run convinced her skipper that this was indeed a submarine; on the next approach Lt. Cmdr. Pendleton launched a salvo of Hedgehog projectiles. Soundman Bernhardt did not hear them detonate but doggedly maintained sonar contact with the wildly maneuvering I-16.

A second volley of Hedgehogs discharged at 1350 hours yielded one muffled explosion. They had hit the sub but not fatally. Two more attacks proved fruitless; in frustration, Pendleton turned the conn over to Lieutenant Williamson. The ship’s captain would observe while his battle-tested XO maneuvered England around for her fifth run against the wily Japanese supply boat. When he judged the time right, Williamson ordered “Fire!”

At 1433 five or six Hedgehogs struck I-16, resulting in a series of rapid thuds. Two minutes later a giant underwater blast shook England, lifting her fantail completely out of the water while knocking sailors to their knees. “At first,” Williamson remembered, “we thought we had been torpedoed.”

In fact, it was the end of Lt. Cmdr. Takeuchi and the 106 other submariners aboard I-16. Soon, proof of its destruction began rising to the surface. Search parties from George and Raby discovered bits of cork, a chopstick, and other wooden debris, while the sudden appearance of a dozen thrashing sharks served as a grim reminder of war’s human cost.

The recovery of a 75-pound bag of rice convinced Commander Hains that his DEs had indeed killed a Japanese supply submarine. England, George, and Raby held station well into the night while all around them grew a massive oil slick, some three miles wide and six miles long, marking the last position of I-16.

Escort Division 39 was not the only Allied force sent out in search of I-16. American patrol planes also scoured the region, flying well into the zone where Admiral Owada had sited the seven Ro-class subs of his NA Line. On May 17, one of these aircraft spotted Ro-104 toward the northern edge of that track and radioed a contact report.

While nowhere near as capable as their adversaries, Japanese signal intelligence operatives could easily intercept and translate plain voice transmissions such as this radio call. The sighting convinced Owada that his picket force had been compromised, so he sent out coded instructions directing the boats of Submarine Squadron Seven to shift their positions 60 miles westward.

FRUPac heard every word. A team of cryptanalysists at Pearl Harbor immediately began work to decipher Owada’s message; within 48 hours they had plotted the exact latitude and longitude of each sub on the relocated NA Line. A courier then delivered this white hot intelligence to Admiral Halsey’s staff for immediate action.

Escort Division 39 was perfectly positioned to intercept Owada’s boats. Late on the afternoon of May 20, Third Fleet sent Commander Hains an exhilarating order: “Seven Japanese submarines are believed to be preparing to form a scouting line in a position between Manus and Truk. Subs 30 miles apart on line. Seek out —attack—and destroy.”

As his destroyer escorts got underway, Hains considered how they would roll up the enemy patrol track. His plan was simple: find the northernmost submarine, sink it, and then swing southwest to snare the remaining boats one after the other. This meant crossing the boundary between Admiral Chester Nimitz’s Pacific Ocean Area and General Douglas MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area, but Hains was authorized to do so if he found himself in hot pursuit of fleeing enemy vessels.

In the early morning murk of May 22, one of George’s radar operators detected a surface contact 14,000 yards off her starboard bow. It appeared to be a submarine, and all three DEs raced forward at flank speed to catch their vulnerable quarry on top. George managed to illuminate the conning tower of Ro-106, commanded by Lieutenant Shigehira Uda, but the submarine crash dived before she could bring her torpedoes or deck guns to bear.

England and Raby circled while their sister ship acquired the target on sonar. George let go one salvo of Hedgehogs at 0414 hours but then mournfully reported that she had lost contact. England’s soundmen heard Ro-106 just fine, though, and Lt. Cmdr. Pendleton soon received permission to take over. Their first run, at 0433, yielded no hits. Either exasperated or superstitious, Pendleton abruptly gave the bridge to Williamson, who had led England to success on her first kill.

Overtaking Ro-106 from its stern, England loosed a Hedgehog volley at 0444 hours. Eighteen seconds later three 24-pound warheads detonated 275 feet below. As before, a huge deep-water explosion marked the final moments of Lieutenant Uda’s boat and its 49 crewmen. England had scored again.

At dawn, watchstanders aboard George sighted an oil slick and some wood fragments adrift in the vicinity of England’s attack. This was sufficient confirmation of Ro-106’s demise, so the tiny flotilla of sub killers turned toward a rendezvous with its next target: Ro-104, Lieutenant Hiroshi Izobuchi commanding.

By sundown, the hunter-killers of Escort Division 39 had closed in on their unsuspecting prey. Nightfall called for a new tactic, and the trio of DEs opened its interval to 16,000 yards between ships to better detect a surfaced submarine. It worked—at 0600 hours on May 23, Raby reported: “We have a radar contact bearing 085 degrees, range 8,000 yards.” The fight was on.

Warned by its electronic emissions receiver, Ro-104 dived in time to avoid Raby’s deck guns but could not stop the aggressive DE from lashing it with sonar pulses. Rapidly changing speed, direction, and depth, the cagy Izobuchi avoided three of Raby’s Hedgehog attacks as well as another four from George. Ro-104 even used its own sonar to ping on the Americans’ frequency, spreading confusion above as the submarine made good its escape.

It was now 0819 hours. Weary of this futile two-hour battle, Hains told Raby and George to sheer off. “Give way to the England,” he ordered with a note of annoyance in his voice, and once more this deadly little warship moved in for the kill. With Lt. Cmdr. Pendleton at the conn, England fired a salvo to starboard that missed. Again, the captain yielded tactical control to his good-luck XO for a second run.

Under Williamson’s direction, England launched a full pattern of Hedgehog rounds at 0834 hours. Fourteen seconds later her soundmen reported at least a dozen hits followed by the now familiar deep-water crash of a dying submarine and the 58 souls aboard it. At Hains’s request, England then dropped 13 depth charges to finish the job.

Within a few hours, telltale debris from Ro-104 along with a spreading oil slick began to surface. England’s whaleboat crew recovered pieces of deck planking and cork stoppers as well as small pieces of wood with Japanese characters imprinted on them. Ravenous sharks also made their appearance, casting a somber mood over England’s company. Jubilation over their recent victories was muted by the knowledge that dozens of human beings were perishing in each attack.

Lieutenant Williamson learned of the crew’s new mood later that day when a young seaman encountered him on his way to the wardroom. After requesting permission to speak, the bluejacket asked how many enemy sailors were on those submarines England had been sinking.

“It depends on the type of sub,” Williamson replied. “Probably somewhere between 40 and 80.”

“Sir,”’ the youth then questioned, “how do you feel about killing all those men?”

The XO could only say that war is about killing, and the more ships they sank the sooner it all would be over. This seemed to reassure the fresh-faced rating but continued to trouble Williamson for the rest of his days. Already England had taken the lives of more men than she had aboard.

Putting aside for the moment such thoughts, England’s company continued its run down the NA Line with the other warships of Escort Division 39. At 0122 hours on May 24, George’s radar detected another surface contact dead ahead at a range of 14,000 yards. This was Ro-116, skippered by Lt. Cmdr. Takeshi Okabe, which crash dived the moment its warning sensors identified George’s distinctive radar emanations.

Okabe fought his boat masterfully. As the trio of DEs passed overhead he kicked his vessel’s rudder into a fishtail maneuver that disrupted the Americans’ firing runs, all the while counterpinging to distract sonar sensors. Okabe also employed rapid up and down movements to further confound the hunter-killers on his trail.

Recognizing he was up against an unusually skilled opponent, Lt. Cmdr. Pendleton wasted no time in putting his executive officer at the helm. Also tracking Ro-116 was lead soundman John Prock, who together with Roger Bernhardt had helped England find and fix three earlier targets. Now Prock suggested a ruse that might keep this bothersome submarine still long enough to enable a Hedgehog attack. During a firing run, the sound crew would normally increase their rate of sonar pulses to more accurately fix a sub’s location. This tactic alerted the enemy below that England was about to attack; Prock recommended keeping a steady ping rate on the next approach.

They gave it a try. At 0214 hours, Lieutenant Williamson yelled, “Fire!” and a flurry of Hedgehogs reached out for the elusive Japanese submarine. A few seconds later, three to five charges exploded at a depth of 180 feet. This time there was no resounding crash to mark Ro-116’s death, but dawn revealed conclusive evidence of its doom in the form of insulating cork, decking, and patches of fuel oil floating around nearby. Scavenging sharks were also sighted. Later, Navy intelligence confirmed that Ro-116 had gone down with all 56 hands.

At this point, Commander Hains needed to make a major decision. His DEs had been fighting hard for six days. Supplies of fuel and especially ammunition were now down to critical levels. Moreover, they were about to enter General MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area, a zone labeled “off-limits” to Third Fleet vessels unless in active pursuit of an enemy sub. Should his flotilla continue on, head for the nearest friendly port, or return to Purvis Bay for resupply?

Hains’s choice was made for him by the arrival on May 26 of Task Group 30.4, centered on the escort carrier USS Hoggatt Bay (CVE-75). Captain William V. Saunders commanded this force sent by Admiral Halsey to assist in antisubmarine operations. After learning of Escort Division 39’s extraordinarily productive week, Saunders directed Commander Hains’s warships to make for Seeadler Harbor at Manus in the Admiralty Islands. This was MacArthur’s territory, and here Lt. Cmdr. Pendleton saw an opportunity to continue the winning streak. Rather than head straight for Manus, Pendleton suggested, why not bend the track “coincidentally” on the same bearing as the enemy’s NA Line? The other skippers agreed.

Now authorized to cross into the Southwest Pacific Area, Escort Division 39 resumed its hunt. That evening, Raby reported a surface contact bearing 180 degrees, range 14,000 yards. One minute later, at 2304 hours, England also acquired the target on radar. It was Ro-108, Lieutenant Kanichi Obari commanding.

All three destroyer escorts charged in, but when Raby fell out of position England took over for a rare surface engagement. Just as her crew was about to launch torpedoes, however, Ro-108 submerged. With John Prock at the sound tower and England’s engine gang slowing her to 10 knots, Lieutenant Williamson maneuvered the agile warship into a bow-attack position. At 2323 hours, he let fly a salvo of Hedgehogs, exactly half the projectiles remaining on board. Any error now would prove embarrassing, if not fatal, for the high-scoring DE.

Williamson need not have worried. A series of muffled blasts from 250 feet down signaled the annihilation of Ro-108 and the 58 men who died with it. The next morning search teams found a huge oil slick as well as numerous pieces of flotsam drifting in the vicinity of England’s attack. Polished mahogany fragments from a chronometer case convinced the crew that one of their Hedgehog charges had struck the enemy sub’s conning tower.

Commander Hains’s warships then made for the American base at Manus, arriving there by 1500 hours on May 27. Awaiting them at Seeadler Harbor was the destroyer escort USS Spangler (DE-696), which had sailed from the Solomons with a welcome resupply of Hedgehog rounds. After spending the night to take on fuel, ammunition, and provisions, the destroyer escorts—now accompanied by Spangler—headed back into the patrol area where Task Group 30.4 was now operating.

The next two days passed uneventfully, but early on May 30, one of Captain Saunders’s destroyers acquired a target and pressed in with depth charges (at this point in the war, fleet destroyers were not equipped with Hedgehogs). George and Raby were close enough to offer assistance; Commander Hains ordered them in while directing England and Spangler to sweep a sector about 30 miles to the south.

So began a two-day battle against one of the most able submarine officers in the Imperial Japanese Navy. Captain Ryonosuke Kato had made Ro-105 (skippered by Lieutenant Junichi Inoue) his flagship and was now ducking every punch the hunter-killers of Escort Division 39 could throw at him. Both George and Raby made multiple attacks throughout the morning, even scoring a few Hedgehog hits, but the stubborn Ro-105 refused to die.

Kato employed every ruse he knew, jettisoning oil and debris while blowing air from his boat’s tanks in an attempt to deceive the prowling DEs overhead. Just after sunset, Captain Kato took more direct action. Snapping briefly to the surface, Ro-105 loosed a brace of torpedoes at its tormentors. All missed but served notice to the Americans that this was an exceptionally dangerous opponent.

Doubling their efforts, George and Raby continued to hound Ro-105 all night. Their crews knew that sooner or later the Japanese boat would run out of breathable air or battery power and be forced to surface. Shortly after 0300 it did—directly between the two DEs. Neither of them could get off a shot, but Raby briefly managed to lay a searchlight beam on the nettlesome submarine before it once again slipped beneath the waves.

That shaft of light caught the attention of England’s lookouts, still 30 miles to the northwest. Together with Spangler, the veteran sub-killer rushed in to offer assistance. At first it was not welcome. “We’re not telling you where we are,” a prickly voice taunted Williamson over talk-between-ship radio. “We have a damaged sub, and we’re going to sink him. Don’t come near us!”

Commander Hains offered a more measured response, keeping England and Spangler off at 5,000 yards while his other two DEs continued to track Ro-105 on sonar. At first light the attack resumed. First George then Raby went forward with Hedgehogs; both missed. “It’s your turn, Spangler,” Hains ordered. She ran in and fired a volley of projectiles, which also failed to connect.

“Okay, England, it’s your turn,” Commander Hains said with resignation. The 30-hour battle came to a close at 0736 hours on May 31 when at least 10 well-aimed Hedgehog charges exploded 180 feet below the surface. Five minutes later a resounding undersea boom sounded the death knell for Ro-105 and its 55 crewmen. Soon too came up the usual field of fuel and wooden detritus accompanied by 10 or so frenzied sharks.

The USS England had just sunk six submarines in 12 days, an unprecedented feat in the chronicles of naval warfare. Yet her mission was not over. FRUPac had reported a total of seven enemy boats on the NA Line; England and her companions spent the next two weeks vainly searching for any remaining subs. Unbeknownst to them, Admiral Owada had once more repositioned his boats. Ro-109 and Ro-112 thus escaped the deadly American hunter-killer teams then combing South Pacific waters.

England’s triumph was more than just an amazing feat of seamanship; it held strategic consequences as well. After learning that most of his submarine pickets had been destroyed, Admiral Toyoda became convinced the American fleet was heading south toward Palau or the Philippines. Issuing orders for Operation A-Go, his decisive sea campaign, Toyoda began moving Japanese forces from the Marianas southward. Consequently, many ships and planes needed to defend the islands of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam were not available when a U.S. invasion fleet appeared off those islands in mid-June.

For this reason, historian W.H. Holmes considers England’s 12-day battle as “the most brilliant antisubmarine operation in history.” Admiral Ernest King, chief of naval operations, expressed his satisfaction in another way. “There’ll always be an England in the United States Navy!” King exclaimed in an uncommonly exuberant congratulatory message.

Security concerns meant the exploits of England and her fellow DEs could not be made public for months. In fact, the key role FRUPac played in this campaign was not recognized until decades later when the U.S. Navy finally declassified its operational records. Great credit also belongs to the crews of George and Raby. While their sister ship made all the kills, these DEs provided invaluable assistance by detecting and running down several enemy submarines.

For their outstanding combat performance, the men of England were awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, making them one of only three destroyer escort crews in World War II to be so recognized. Receiving the Navy Cross and promotion to commander, Walton Pendleton left the ship he loved to command an escort division in Alaska until war’s end.

And John Williamson, the officer who had contributed so much to England’s record of accomplishment, received the best prize of all. When in September he again took USS England out to sea, Williamson did so as her newly assigned commanding officer.

Patrick J. Chaisson is a retired military officer who writes from his home in Scotia, New York.

Mr. Patrick Chaisson,

My father, Lt. Charles J. Spletter, was the Recognition Officer aboard the USS George during this operation. He joined the ship on May 15, 1944, a day or two before Escort Division 39 embarked on this highly successful mission. I have his binoculars he used on deck or in the “Crow’s Nest”. I also have many of his original navy orders during his enlistment.

The USS George’s cook, Richard Hillyer, wrote a book (and I have a copy) about these exploits and maintained that the USS England got only four of the six Japanese subs. He offers proof of this fact. Interesting!

That is very interesting. You have an amazing personal connection to this story, not to mention a valuable historical artifact (your father’s binoculars). Thank you for your comment. I will look for Hillyer’s book. — PJC

Did the other two commit Hary-Kary?