By Mark Carlson

In 1982, Captain Bert Earnest and Commander Harry Ferrier were present at an event to commemorate the 40th Anniversary of the Battle of Midway. The guest of honor was George Gay, the lone survivor of the doomed Torpedo Squadron 8. Gay talked about the battle and his lost squadron mates. Eventually one man noticed Earnest standing nearby and asked him who he was.

“Oh,” said Earnest, glancing at Ferrier, “we’re the other ‘lone survivors’ of Torpedo 8.”

The June 1942 Battle of Midway has sparked its share of legends, but the most enduring is the tragedy of 15 obsolete TBD Devastators of USS Hornet’s Torpedo 8 flying into a swarm of Japanese Zeros and antiaircraft fire as they attempted to launch torpedoes at Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s carriers. Of the 30 men of Torpedo 8 who took off from Hornet that morning, only Ensign George Gay survived. Gay became an immediate celebrity. Featured in newspapers, wined and dined by movie stars and politicians, he was the symbol of the doomed aviators of Torpedo 8.

But contrary to popular belief, Torpedo 8 was not destroyed. Lieutenant Commander John Waldron only led half of the squadron. They flew the slow and vulnerable Douglas TBD Devastator, which was even then being replaced by the newer, faster and more powerful Grumman TBF Avenger. The rest of the squadron was still on Naval Air Station Ford Island at Pearl Harbor with their new TBFs. Torpedo 8 was the first squadron to receive the new torpedo plane. The other pilots and gunners were under the command of Lieutenant Harold “Swede” Larson, an Annapolis graduate who ruled with an iron fist. They had arrived from Norfolk with their planes aboard two transports the day after Hornet left Pearl, too late to participate in the carrier battle.

Ensign Albert “Bert” Earnest, who had joined the squadron six months earlier, was a 25 year old from Richmond, Virginia. He had started flight training at Pensacola in February 1941. Upon receiving his wings in November, he reported to VT-8 at Norfolk three days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. “The Hornet was leaving in about a month,” Earnest said. “Commander Waldron decided who would go with the ship. The newest men would remain behind to be trained on the new TBF-1. When we finally reached Pearl at the end of May, the Enterprise and Hornet were already gone, and Yorktown was still in drydock. The next morning Yorktown was gone.”

Earnest loved the TBF. With close to 90 hours of flight time he felt good about the power and speed of the new bomber. “The Devastator was a fairly good airplane but its time was long past. It was quite slow especially after you put on a torpedo. That slowed it down a great deal. The TBF was much, much faster and carried the torpedo internally.”

Even as the American carriers raced to place themselves in harm’s way, another desperate phase of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s daring scheme was underway at Midway. A motley collection of Army, Marine, and Navy planes were being hastily assembled to beef up the island’s air strength. Among them would be six of Torpedo 8’s new TBFs. Larson was ordered to choose the six planes and their crews that were most ready for combat and send them to Midway. But Larson was not to go with them. The leader of the detachment would be 32-year-old Lieutenant Langdon Fieberling. The TBFs would carry long-range fuel tanks for the 1,200-mile flight to Midway, where they were to be ready for an attack on the Japanese striking force. It was a tall order. None of the pilots or airmen had ever been in battle. Few had ever dropped a live torpedo or even had experience in long over-water flying. But they went to Midway to do their part in the most desperate battle of the Pacific war.

The Grumman TBF, which did not yet bear the name “Avenger,” had been developed as the most advanced long-range torpedo and level bomber for the Navy’s carrier fleet. The prototype had first flown in August 1941. They were only now rolling off the Grumman assembly line on Long Island. Built to the Grumman “Iron Works” rugged standards, it was a massive plane with a 54-foot wingspan and towered over 15 feet high. A Wright Cyclone R-2600 1,950-horsepower engine drove the five-ton bomber and her three-man crew for 1,000 miles at 275 knots. The payload was a single 2,000-pound torpedo or a ton of bombs or depth charges. For defense, the early models carried twin forward-firing .30-caliber Browning machine guns in addition to the single .50-caliber in the dorsal ball turret and .30-caliber in the ventral position. They saw service throughout the Pacific War and participated in some of the most important campaigns against Japanese ships and land installations. But in June 1942, they were an unknown entity in the air war.

At 0600 on June 1, the six planes were fueled. Each was painted in the light blue and pale gray scheme used by the Navy in 1942. Larson made up some large decals bearing the squadron’s emblem of a clenched fist with the word “attack!” With a wave, Fieberling led them off NAS Ford Island at 0700 hours. The new Wright Cyclone engines pounded out the smooth cadence of power as they climbed to 1,500 feet and took up a compass heading of 270 degrees to the west. Fieberling was leader of the first three-plane element with Bert Earnest trailing on his left wing and Ensign Charles Brannon on his right. Behind them were Ensign Ozzie Gaynier with wingmen Victor Lewis and Darrell Woodside trailing behind.

Unlike most of his squadron mates, Earnest had actually dropped a torpedo during training at NAS Quonset Point in Rhode Island. He thought that may have been why he had been selected to join the detachment. Seated in the turret at the rear of the canopy was Gunner’s Mate Jay Manning, and in the lower compartment under the turret was Radioman Harry Ferrier from Springfield, Massachusetts. Both were still in their teens. In fact, Ferrier was only 17, having altered his birth certificate to join the Navy at 15. Ferrier could only see out of the small side and back windows of his ventral position. Below the TBF was a vast, empty blue ocean.

“I never saw a ship on that entire flight,” he later recalled. Eight hours after leaving Pearl Harbor, the big Grumman planes approached Midway. The antiaircraft gunners were warned of the incoming torpedo planes. “What’s a TBF?” one gunner had asked. “What does it look like?”

“It looks like a pregnant F4F Wildcat,” he was told. When Fieberling’s planes arrived over the island, not a finger touched a trigger.

Ferrier saw the runways on Eastern Island lined wingtip to wingtip with 16 B-17s and four brand-new Martin B-26 Marauders, as well as 20 Consolidated PBY Catalinas, 26 Marine fighters, and 32 dive bombers. Ferrier said that there were so many it seemed they would barely have room to land. Yet some of the planes were long past their prime. The Marine F2A Brewster Buffalo fighters were woefully obsolete, while the Vought Vindicator dive bombers had surgical tape patching the control surfaces.

After the VT-8 men found cots in tents along the airfield perimeter, they learned that a huge Japanese fleet was coming to attack and invade Midway. The tiny atoll was where the U.S Navy had chosen to make its stand. Earnest wasn’t scared. He knew his job, and the TBF was the best plane for that job. He was sure they could hold their own when the battle began. “We were told that the carriers were protecting the Hawaiian Islands. We shouldn’t expect any help from them. We were on our own.”

Ferrier and Manning had an idea. They affixed wide masking tape to the leading edges of the wings, about where machine guns would be on a fighter. Then they inked black holes on the tape to appear as gun ports. They hoped this might make some Zero pilot think twice about attacking it.

The Americans knew what was coming, but were hardly able to stop it. At 0430 on the morning of June 4, the first wave of 36 Japanese A6M Zeros, 36 D3A Val dive bombers, and 36 B5N Kate level bombers took off from Nagumo’s four carriers. At that moment Earnest was awakened by the heavy roar of big radial engines as the 16 B-17s took off. He headed to his TBF and began preflighting it. Ferrier and Manning checked their guns and equipment. To the left and right the other pilots and crews did the same.

The dawn sky lightened as the Torpedo 8 aircrews waited for orders to take off. Somewhere out there, a huge battle was about to be fought. At 0555 the SQR-270 radar picked up a series of contacts at 175 miles, coming south toward Midway. Instantly the alarms went off and the island’s Navy and Marine defenders took their positions. In the air went the Wildcats and Buffalos of Major Floyd “Red” Parks’s VMF-221. Their job was to intercept and shoot down as many of the incoming bombers as possible.

Then, amid the howling sirens, Earnest watched as a jeep drove up and a Marine officer called out to Fieberling that the Japanese fleet had been sighted. “Another Marine yelled up to me that the Japanese force was at 320 degrees, 150 miles,” said Earnest. “We started the engines and took off right after the [Marine] fighters. But we were on our own. No fighters at all. They were needed for the defense of Midway.” In the radio gunner’s compartment, Harry Ferrier looked out the small window and saw the island fall away as they banked to the north.

Lieutenant Langdon Fieberling was easygoing and unruffled in the most trying of circumstances. He was the perfect man to lead his small detachment into battle for the first time. His TBFs were to join up with the B-26s and Marine dive bombers to make a combined attack on the Japanese fleet. But this would prove to be impossible. The mixed bag of Navy, Army, and Marine planes flew at different altitudes and speeds. The Vindicators were 100 knots slower than the new TBFs. But some of Waldron’s independent nature had worked its way into Fieberling’s own personality. In the end, he told his pilots they would find the enemy carriers and attack, alone if necessary. Their planes were armed with a single Mk 13 aerial torpedo. The Mk 13 weighed 2,200 pounds with a 600-pound Torpex warhead. Having a range of 6,000 yards, it could do great damage to a thin-hulled aircraft carrier. But carriers were fast and maneuverable, and the only way to guarantee a hit was to move in low and get as close as possible before dropping the “fish.”

They climbed to 2,000 feet and took up the heading of 320 degrees at 160 knots. Then a formation of enemy planes passed them and one Zero peeled off to make an attack but was apparently recalled. That was the first Japanese plane they had ever seen. It would not be the last. Just as the island disappeared over the southern horizon the first wave of Japanese bombers and fighters began their attack on Midway. Bright blasts of exploding bombs and antiaircraft guns punctuated the columns of black smoke that rose into the morning sky.

They climbed to 4,000 feet into the scattered clouds. At 0655 hours Earnest, farthest to the left, saw a single ship headed south. It looked like a transport. Then suddenly the whole ocean was covered with ships. “It looked like the whole damned Japanese Navy,” he said. “A massive battleship was just ahead and beyond that, he saw two big carriers steaming side by side.”

The two carriers were the Akagi, flagship of Admiral Nagumo, and Hiryu, steaming 5,000 yards apart, while the other two carriers, Kaga and Soryu, were 10,000 yards behind. Their course was 140 degrees, about south-southeast. Their flight decks were packed with fighters and bombers being fueled and readied for a possible attack on any U.S. ships that might be in the area.

Unknown to the Torpedo 8 detachment they were in fact the spearpoint of the entire American attack. But instantly the Torpedo 8 men were no longer alone in the sky.

“Enemy fighters!” Jay Manning called over Earnest’s interphone. The turret’s .50-caliber began banging away as Manning turned and aimed at the darting Zeros. Earnest had never seen such nimble and swift fighters. “There were so many they were getting in each other’s way. I triggered my nose guns but nothing happened.” Nagumo’s carriers were protected by at least 24 A6M Zeros, veterans of the attack on Pearl Harbor. They had six targets. Cannon shells and 7.7mm machine-gun bullets tore into the big TBFs. Earnest felt and heard the thump and zing of enemy fire tearing through his plane.

Still holding formation, the Americans moved in at full power. Fieberling began his attack run, diving at the sea towards one of the carriers.

Then Jay Manning’s gun stopped firing. In the ventral compartment, Ferrier felt something warm and sticky running over his head and shoulders. It was Manning’s blood. A 20mm cannon shell had exploded in his chest, killing him instantly

Fieberling’s TBF leveled off at 200 feet as the Zeros followed them down. Earnest saw his leader’s bomb bay doors open, and he followed suit. More bullets lanced into Earnest’s plane, and the howl of the 250-knot airstream added to the din of aircraft engines and gunfire. Tracers streaked all around them as he tried to concentrate on the Hiryu which grew larger with every passing second. Suddenly, he felt a sharp blow on his neck as shrapnel hit him. Blood sprayed over the instrument panel. Another Zero moved in behind the TBF.

Ferrier was about to fire when the tail wheel fell, blocking his view. The hydraulic system had been hit. Unable to fire, he could only wait. The big Grumman was taking fierce punishment as dozens of bullets tore into the thin aluminum skin. Earnest felt the plane slipping out of formation as his control cables were shredded. Pulling back on the control stick had no effect. He could not climb or dive. Then a cannon shell exploded in the instrument panel. Unable to control the TBF, he knew they were going down.

The five remaining torpedo planes were boring in amid a swarm of fighters and increasing antiaircraft fire. Just then one of them burst into a ball of orange flame and spun into the sea with a titanic splash, but the others tried to get as close as they could to the huge ship. Two of them managed to release their torpedoes, but the Hiryu was able to avoid them. One by one, the rest of Earnest’s squadron fell from the sky and crashed into the sea. Not one torpedo hit the ship. Fieberling, Brannon, Gaynier, Lewis, and Woodside were all dead, along with their gunners. They had died before Lieutenant Commander Waldron’s 15 Devastators had even launched from the Hornet. The first casualties of the attack on the Japanese fleet had been men of Torpedo 8.

But Bert Earnest and Harry Ferrier were still alive. Against all odds, their shot-rent and shattered TBF was still flying. Earnest had no elevator controls, no hydraulics, no radio or navigational instruments. He still wanted to try and sink an enemy ship. Just ahead to the left was a cruiser, antiaircraft guns blazing away. With a kick on his left rudder, he cobbled the crippled TBF around and aimed at the enemy ship and triggered the switch to release the torpedo. Expecting to feel the sudden release of weight he was surprised that nothing happened. He tried the emergency release with the same results. The torpedo would not fall free of the plane. The big plane slipped closer and closer to the rolling swells, and there seemed no way to stop it.

Then Earnest did something that had become a habit during training. “I had my hand on the elevator trim wheel and the plane suddenly jumped up. I realized I could still control the elevator that way. But I had two Zeros coming at me. Then they left. I don’t know why. They had me dead to rights.”

That was when the USAAF B-26 Marauders bored in on the carriers with their own torpedoes. After that came the Marine dive bombers. Earnest was north of the fleet, with the Japanese between him and Midway. “I decided to head south until I was past the fleet until I figured I was west of Midway.” But all his navigational instruments, including his compass were shot away. “The sun was relatively low in the sky so I knew where east was. I climbed to about 4,000 feet.” There were several planes in the distance heading south but he had no way of knowing who they were. They were probably Marine dive bombers returning home after being savaged by the Zeros.

Somehow Earnest’s damaged plane kept going. The big Wright Cyclone, despite being hit several times, never faltered. With no compass or airspeed gauge, he was going to have to be extremely lucky. If he missed Midway, he and Ferrier were doomed to vanish into the empty sea. As he coaxed the crippled TBF south, Ferrier came on the interphone. “He said he had been knocked out but was okay. I asked if he could see if the torpedo was gone, but there was so much blood from Manning covering the small window into the bomb bay he couldn’t see.”

About an hour after leaving the enemy fleet behind, Earnest turned east. Eventually he saw a smudge of dark gray, which resolved itself into columns of black smoke rising from the island. He lowered his altitude and lined up on the runway for a landing. But his troubles were not over. “I couldn’t get one wheel down,” he said. “I didn’t have any flaps or hydraulics.” With consummate skill, the aviator managed to bring the battered TBF into a one-wheel landing, skidding to a noisy stop just off the runway.

The main attack by the carrier-based Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers was then wreaking havoc on the first three Japanese carriers. All but one of the VT-8 men that left with Waldron were dead. But the bloody day had been an American victory.

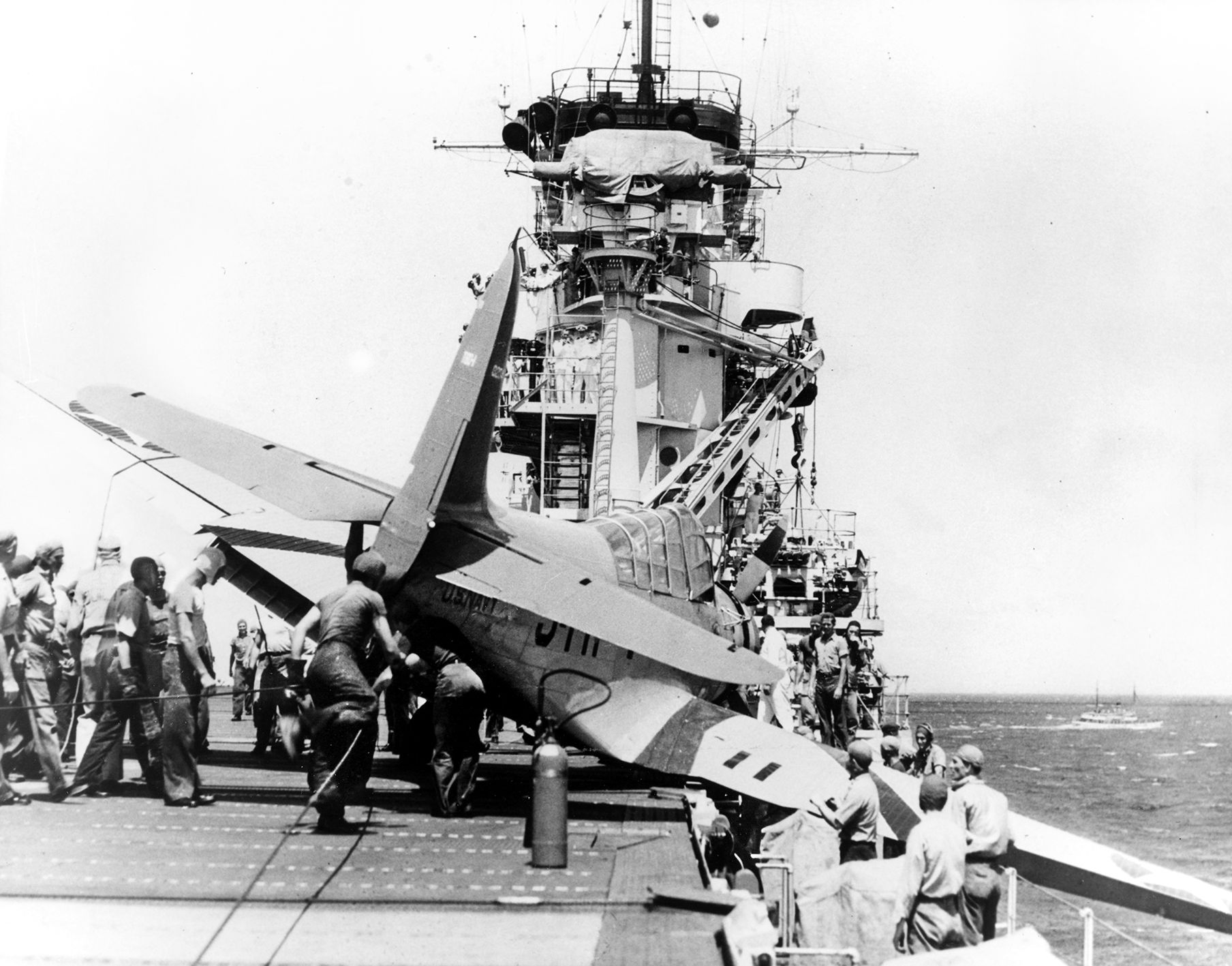

After landing, Earnest found the torpedo had released. The single surviving TBF was found to have nearly 100 holes from small and large caliber shells. Even all three propeller blades were riddled. But that tough Grumman beast never let its pilot and crew down. It was shipped back to Pearl, where Grumman aeronautical engineers examined it with respectful awe. After the battle, the name “Avenger” was given to the new plane.

As for Torpedo 8, the squadron reassembled in Hawaii and shipped out on the USS Saratoga in August. They were headed for a small island in the Solomons called Guadalcanal. The war had just started for the men of VT-8.

After the long and desperate Guadalcanal campaign, Earnest served 30 years in the navy, rising to the rank of captain. He flew B-17s as a hurricane hunter and commanded the Naval Air Station at Oceana, Virginia. Harry Ferrier continued to fly Avengers throughout the war, seeing combat from the Enterprise. He was commissioned as an Ensign in 1945, and retired as a commander in 1970.

The author highly recommends Robert Mrazek’s excellent 2008 book A Dawn Like Thunder—the True Story of Torpedo Squadron 8.

Mark Carlson writes on numerous topics related to World War II and the history of aviation. He lives in San Diego, California.

Thanks for a good article. For an honest description of the scandalous operations of the Bureau of Ordnance’s insistence on using a poor excuse for a naval torpedo read “The Unknown Battle of Midway” by Alvin Kernan. The developoment of this main weapon, and the conditions of its use, are well described, and the time it took to remedy the situation despite the pleas of those on the front lines, are well documented. We have to always honor the extreme sacrifice made by those brave aviators, knowing that their chances of success were extremely small but pressing on ahead anyway.