By Mark Albertson

On September 14, 1939, Igor Sikorsky attained stability and control with the initial flight of an open cockpit test bed known as the VS-300. Thus, Sikorsky introduced to the world the first working single rotor helicopter and fostered the basic design for rotary wing aircraft that has endured to the present day.

On May 26, 1940, Sikorsky arrived at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio. He showed a film on the VS-300 to an audience from the Army Air Corps’ Material Division. The pitch to get Washington to open its wallet worked. Funds, though, were limited since the Army was already invested in the XR-1 from the Platt-LePage Aircraft Company. However, the Platt-LePage offering was plagued by controllability issues. Nevertheless, Sikorsky submitted a proposal to produce another design, the VS-316, for $50,000. The Army agreed, and a contract was signed on January 10, 1941.

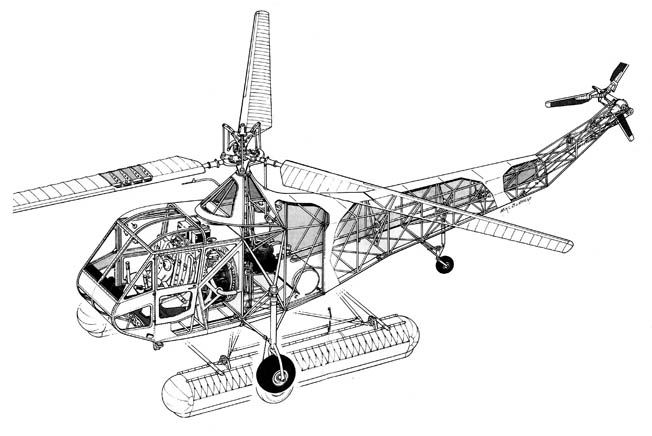

The original VS-316 design featured three tail rotors, a vertical rotor mounted in the center flanked by horizontal rotors. The design change to a single vertical rotor added $10,000 to the original contract. Approximate development costs for the follow-on experimental XR-4 amounted to some $200,000.

The first flight of the XR-4 was on January 14, 1942. In an effort to demonstrate controllability, test pilot Les Morris auto-rotated the platform. Then on April 20, 1942, the XR-4 was flown before an audience representing a variety of interests. The impressive demonstration included the XR-4’s vertical capabilities, such as ascents and descents, and the ability to hover as well as flying backward and sideways. The potential for amphibious operations was augured with the addition of floats, enabling both landings and takeoffs from land and water. A passenger entered and exited the hovering XR-4 by use of a rope ladder, offering a glimpse into rotary wing rescues. The future of battle zone transport was forecast when Sikorsky’s design hoisted a payload of more than 700 pounds.

The demonstration was followed by a discussion on possible roles and missions for the helicopter such as medical evacuation, light transport of personnel and stores, aerial artillery fire direction, aerial photography, observation and reconnaissance, rescue duties, wire laying, and other tasks.

The successful April demonstration set the stage for a record-breaking flight by a rotary wing aircraft. The Army wanted the XR-4 flown from the Sikorsky plant in Stratford, Connecticut, to Wright Field in Dayton. Up to this point, the XR-4 had been hardly a mile from the assembly line in Stratford. Morris made a number of short hops to make sure the helicopter was mechanically sound, and on May 13, 1942, he lifted off.

Factory personnel tailed Morris in a car, offering tools, spare parts, and assistance. However, Morris made it to Dayton, touching down on May 17 after covering more than 760 miles in five days. Total elapsed flight time was 16 hours and 10 minutes. The longest stretch was in Ohio, from Mansfield to Springfield, 92 miles flown in one hour and 50 minutes. Following this impressive demonstration, the Army agreed to accept delivery on May 20.

The Army ordered 15 XR-4 models for development. Another 14 XR-4s followed in January 1943. Later that same year a production contract for 100 R-4Bs was issued by the U.S. Army Air Forces.

Lieutenant Colonel Frank Gregory of the Army Air Forces was an avid proponent of the helicopter. He is reputed to have advised Igor Sikorsky to change the tri-rotor tail assembly on the VS-316 to a single rotor. On May 6 and 7, 1943, Lt. Col. Gregory endeavored to prove that the helicopter could operate from a ship. A tanker, the Bunker Hill, was anchored in Long Island Sound, a couple of miles east of Stratford Point Light. Operating to and from a 78-foot long section of the tanker’s deck, Gregory took off and landed 23 times, proving the helicopter could operate from ships at sea.

The Coast Guard, too, performed yeoman service in the development of the helicopter, and Commander Frank A. Erickson proved an eager advocate, believing that the potential inherent in the helicopter afforded it advantages over fixed-wing aircraft when tracking or shadowing submarines. Helicopters could hover, operate vertically and horizontally, and drop sonar buoys or depth charges. Escort vessels or merchant ships could carry helicopters, supplementing escort carriers assigned to convoy protection.

Erickson also saw in the helicopter the agent of mercy for the wounded. And he was able to prove this supposition in a Sikorsky HNS-1 (R-4).

At 0615 hours, January 3, 1944, the destroyer USS Turner (DD-648), while riding at anchor in Ambrose Channel off Sandy Hook, New Jersey, was rocked by an explosion near the number 2 5-inch magazine and handling room. Fires raged forward, and the tincan became an inferno. Many men were killed, including the Turner’s skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Henry S. Wygant. Then a second detonation, this time near the number 1 5-inch magazine and handling room, sent flames racing through the stricken ship. Oily plumes of smoke roiled off Sandy Hook. In minutes 20mm ready ammunition began to explode, sending tracers skyward. The destroyer settled into the shallows at 0827, taking 15 officers and 138 sailors to a watery grave. Just two officers and 163 bluejackets remained, many horribly burned.

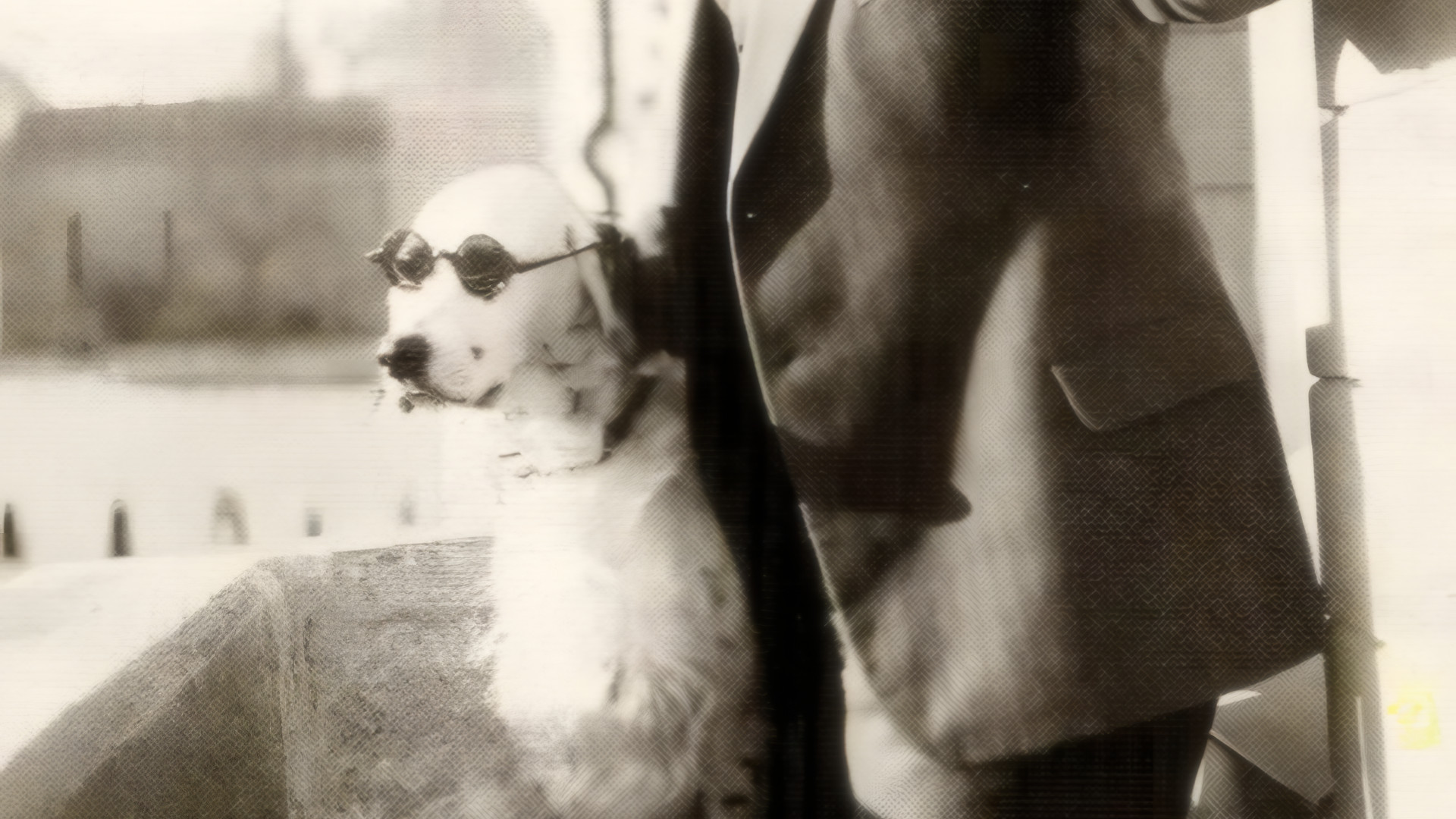

Stricken sailors were rushed to the hospital in Sandy Hook. Owing to the nature of the injuries, supplies of plasma quickly ran low. Enter Lieutenant Frank A. Erickson, who secured two cases of plasma to the floats of his HNS-1 and lifted off. Through gusty winds and driving snow, the intrepid Coast Guardsman weaved his way through the concrete canyons of New York City. He reached Sandy Hook and touched down. Erickson saved many a sailor in what is reputed to be the first lifesaving mission flown by a helicopter.

But the Coast Guard cannot take all the bows. The first rotary wing combat rescue in history goes to the Army Air Forces, April 26-27, 1944.

On April 21, 1944, Technical Sergeant Ed Hladovcak crashed his L-1 Vigilant observation plane in Burma, miles behind Japanese lines. Aboard were three British commandos, all of whom were wounded. A prowling L-5 Sentinel liaison aircraft overflew the crash site, but there was no place set down for a rescue.

Sergeant Hladovcak and his charges melted into the jungle. Japanese soldiers swarmed the wreck. They found no bodies and began to beat the bushes for survivors. Hladovcak and the commandos held their collective breath as Japanese soldiers poked and prodded the undergrowth.

Later in the day, an L-5 from the 1st Air Commandos pinpointed the quarry, and the pilot dropped a note: “Move up mountain. Japanese nearby.” Another message drop told of a sandbar on a nearby river, which had been secured by British commandos and was large enough for an L-5 to set down and pick up the stranded men.

The condition of the wounded worsened, which meant a trek through the jungle was out of the question. So Colonel Philip Cochran, famed commanding officer of the 1st Air Commandos, made a decision. “Send the eggbeater in!”

Earlier that month, four helicopters, together with crews and mechanics, arrived in Lalaghat, India, attached to the 1st Air Commandos. Within weeks, owing to mechanical deficiencies and crashes, only one was still flying. This left Lieutenant Carter Harmon as the sole rotary wing pilot flying the only helicopter available.

Harmon was ordered to take off from Lalaghat and head for Taro in northern Burma, a trek of 600 miles. This was 500 miles beyond the range of the R-4. Harmon acquired four Jerry cans of fuel, giving him another 21 gallons.

Harmon lifted off for the first leg of the journey. The eggbeater passed its first real test by clearing a 5,000-foot-high mountain range. Between refueling stops, it took Harmon another 24 hours to reach Taro.

Harmon was ordered to proceed another 125 miles south to a temporary landing strip known as Aberdeen, a 1st Air Commando base behind Japanese lines. To give Harmon an edge, mechanics scrounged a gas tank from an L-5 and installed it in the R-4. Harmon took off, arriving at Aberdeen on the morning of the 25th. The plan called for Harmon to leave Aberdeen and rendezvous with the waiting L-5 at the sandbar. From there, Harmon would have to extricate the unfortunates and return to the sandbar for the L-5 to fly them out. Harmon would have to traverse a jungle infested with Japanese, attempting an untried concept in an inhospitable environment in an aircraft that, at this juncture, was suspect at best. Harmon could lift just one passenger at a time. Burma’s excessive heat and humidity so limited the YR-4B that Harmon could barely hover with only himself on board.

Harmon employed a technique familiar to many of today’s helicopter pilots who have survived similar situations. Jerking the vertical lift controls caused the helicopter to pop momentarily in the air. Nosing the aircraft forward quickly but gently from the top of this pop would probably provide sufficient forward speed and airlift to fly away if he did not crash first. Harmon’s “field expedient” takeoff was successful. Harmon plucked one of three commandos and shuttled him to the waiting Stinson. Then he went back for another. He had no trouble retrieving his second passenger, but upon arriving at the landing zone there was a sickening “clunk” followed by a smell that indicated trouble. The engine was overheating. Harmon set the R-4 down. Sikorsky’s creation needed to cool. Harmon and the eggbeater spent the night on the sandbar.

A low ceiling greeted the new day. Otherwise, the weather was favorable. Harmon picked up the remaining commando, dropped him at the rendezvous, and then started back for the last man, Ed Hladovcak.

The downed airman heard the approach of his taxi to freedom. Harmon cleared the trees and began to descend. Suddenly, uniforms broke from the tree line. Harmon waved frantically and shouted. Japanese troops were closing in.

Harmon touched down. Hladovcak jumped in. The Sikorsky lifted heavily from the jungle floor. The enemy soldiers swarmed beneath the chopper. Then the R-4 seemed to heave as if ready to convulse. The two men held their collective breath. There was no clunk, no aroma of disaster. Both rescuer and rescued were on their way. Harmon flew Hladovcak back to Aberdeen.

There was a tragi-comic irony to Hladovcak’s rescue. The troops overrunning the landing zone were not Japanese, but Chindits braving the jungle in a vain attempt to deliver those who had been trapped.

Harmon’s feat set in motion a trend. Other rescues followed as the helicopter was beginning to prove itself on the battlefield, gaining converts and generating interest in that ungainly aircraft Phil Cochran had so winsomely called the eggbeater.

But the helicopter’s case would be fueled, in part, with the advent of a weapon that would change the face of war, the atomic bomb. In July 1946, Operation Crossroads, the atomic tests at Bikini Atoll began. Among those in attendance was Lt. Gen. Roy S. Geiger, commander of the Fleet Marine Force in the Pacific. Geiger was an experienced amphibious assault officer, having commanded the III Amphibious Corps. Geiger did not believe that the United States would retain its monopoly on the atomic bomb. On August 21, 1946, he wrote to General Alexander Vandergrift, Commandant of the Marine Corps:

“Since our probable future enemy will be in possession of this weapon, it is my opinion that a complete review and study of our concept of amphibious operations will have to be made…. It is quite evident that a small number of atomic bombs could destroy an expeditionary force as now organized, embarked and landed…. I cannot visualize another landing such as was executed at Normandy or Okinawa.”

This communication led to a special board headed by Maj. Gen. Lemeul C. Shepherd, Jr.

The objective was to research the effect of atomic weapons on amphibious operations. The result was the concept of vertical assault relying on rotary wing aircraft as an alternative to moving troops from ship to shore in amphibious operations.

The Army, too, would follow suit. During the Korean War, the helicopter was used to move stores and supplies, evacuate wounded, and shuttle troops to and from the battlefront.

In 1944, Lieutenant Carter Harmon showed the potential of the helicopter once again in the steaming jungles of Burma. Twenty years later, the helicopter would go on to become the poster child for the American effort in Vietnam. Sikorsky’s R-4 set the basic design cue for helicopters to the present day. Beginning with the cockpit, plexiglass was featured throughout. Doors with roll-up windows provided entry and exit from each side of the cockpit. Seating was side by side, but the pilot was positioned on the right. When the R-4 was used for training, the instructor moved to the left seat while the student pilot sat on the right side.

The 200 horsepower Warner Super Scarab, 7- cylinder, air-cooled radial powerplant sat just abaft the cockpit. Mounted backward, a drive shaft stretched rearward and connected to a short drive shaft running to the main gearbox. Shafts from the gearbox drove the main and tail rotors.

The fuselage was of two-piece construction bolted together just aft of the powerplant. “The aft structure was almost entirely round steel tubing, but the forward part also included square-section steel tubing and wooden stringers,” commented one aircraft expert. “The after framework was covered with doped fabric to reduce drag. Zippers were sewn into the fabric at various locations to allow access to components for inspection and maintenance. The forward structure, containing the engine compartment and cockpit, was covered with removable panels made from thin sheets of dural (hardened aluminum alloy) or magnesium alloy. The fuselage framework was constructed almost entirely of 4130 chrome-molybdenum steel thin wall tubing.”

The XR-4 was initially designed with three tail rotors, a single vertical tail rotor flanked by a pair of horizontal rotors. This configuration gave way to a single vertical antitorque rotor. The main rotor was three blades, 38 feet in diameter and tapered. “The blades were primarily of wooden construction,” said author Thomas H. Lawrence. “The main rotor blade had a steel tube at the quarter chord location. Ribs, built-up from plywood, were placed along the spar using brackets to hold against the centrifugal force. The forward part of the airfoil was covered with this plywood to provide a smooth surface and increase stiffness, while the aft part was covered with fabric to reduce weight and maintain the blade center-of-gravity forward of the quarter chord location. The training edges of the ribs were tied together by steel strapping to maintain the airfoil contour and resist edgewise bending caused by Coriolis forces.”

The landing gear of the R-4 featured a tail wheel plus two other wheels mounted on struts that were affixed to each side of the fuselage abaft the pilot and observer. A skid was available for the nose to prevent rollovers, or the wheels could be removed and replaced by a pair of pontoons.

Author Mark Albertson resides in Norwalk, Connecticut.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments