By David H. Lippman

Lieutenant General Erwin Rommel, a rising star in Germany’s equally rising war effort, was tasked with saving Italy, Germany’s key ally, from a grave disaster in North Africa. He would do so and, in those victories, the “Desert Fox” would become a military legend that would continue to the present day.

By February 1941, the Axis situation in Africa was quite grave. A force of 30,000 Britons, Australians, and Indians making up three divisions had defeated an Italian army of 10 divisions in Libya, bagging 130,000 prisoners and capturing 850 guns and 400 tanks, for a loss of less than 2,000 men. The one-sided Allied victory boosted their morale, humiliated Fascist Italy, and put British troops a step away from conquering the entire colony.

With Italian troops also bogged down in a failed invasion of Greece, Adolf Hitler could afford no further humiliation of his ally and one-time mentor, Benito Mussolini. Even as Italian troops were fleeing westward to Tripoli, Mussolini pleaded with Hitler to provide a “blocking force” to protect Libya’s capital.

Hitler was planning a variety of offensives against the obstinate British—attacks on Malta, Gibraltar, Greece, and Crete—and sending two mobile divisions to North Africa would fit in well. He intended to fight his war in North Africa on the cheap, so as not to distract from his primary objective, the invasion of the Soviet Union.

Chosen to lead the force was Rommel, a bold Swabian and career military man, who had earned the Reich’s highest decoration for valor—the Pour le Mérite (now often referred to as the“Blue Max”)—by leading successful attacks in the Romanian and Italian mountains during the Great War. After Versailles, he stayed in the army, becoming a renowned instructor. He had published a collection of his lectures as a book, The Infantry in Attack, which had impressed Hitler. During the invasion of Poland, Rommel, now a major general, had commanded the unit that guarded Hitler and his retinue. A skillful self-promoter, Rommel had used that position to persuade the Fuehrer to give him command of the new 7th Panzer Division, preparing for the invasion of France. In that campaign, Rommel had gained ground and the attention of German propaganda efforts with his bold style, victorious battles, and frontline leadership. His private life was also appropriately wholesome. He was devoted to photography, stamp collecting, and his family. He seemed an appropriate choice for this high-profile assignment.

Two German divisions, the 15th Panzer and the 5th Light, both fully motorized units, were picked out and ordered to Tripoli to reinforce other Italian divisions already on their way there. All German and Italian mobile forces would come under Rommel’s command in what would be called the “Afrika Korps.”

Rommel himself arrived in Tripoli on February 12, to find Italian troops having thrown away their weapons to jam overloaded trucks and flee to the city, junior officers packing their bags to head for Italy, and the local commander dubious about holding the city.

Rommel wasted no time, boarding a Heinkel He-111 bomber for a personal look at the battlefield. Then he ordered the two arriving Italian units, the Brescia and Pavia Infantry Divisions of the 10th Corps, to halt the British advance. While they did so, Italy’s best armored unit, the Ariete (Ram) Division, under Gen. Ettore Baldasarre, would deploy its 80 obsolescent M13 tanks behind the infantry.

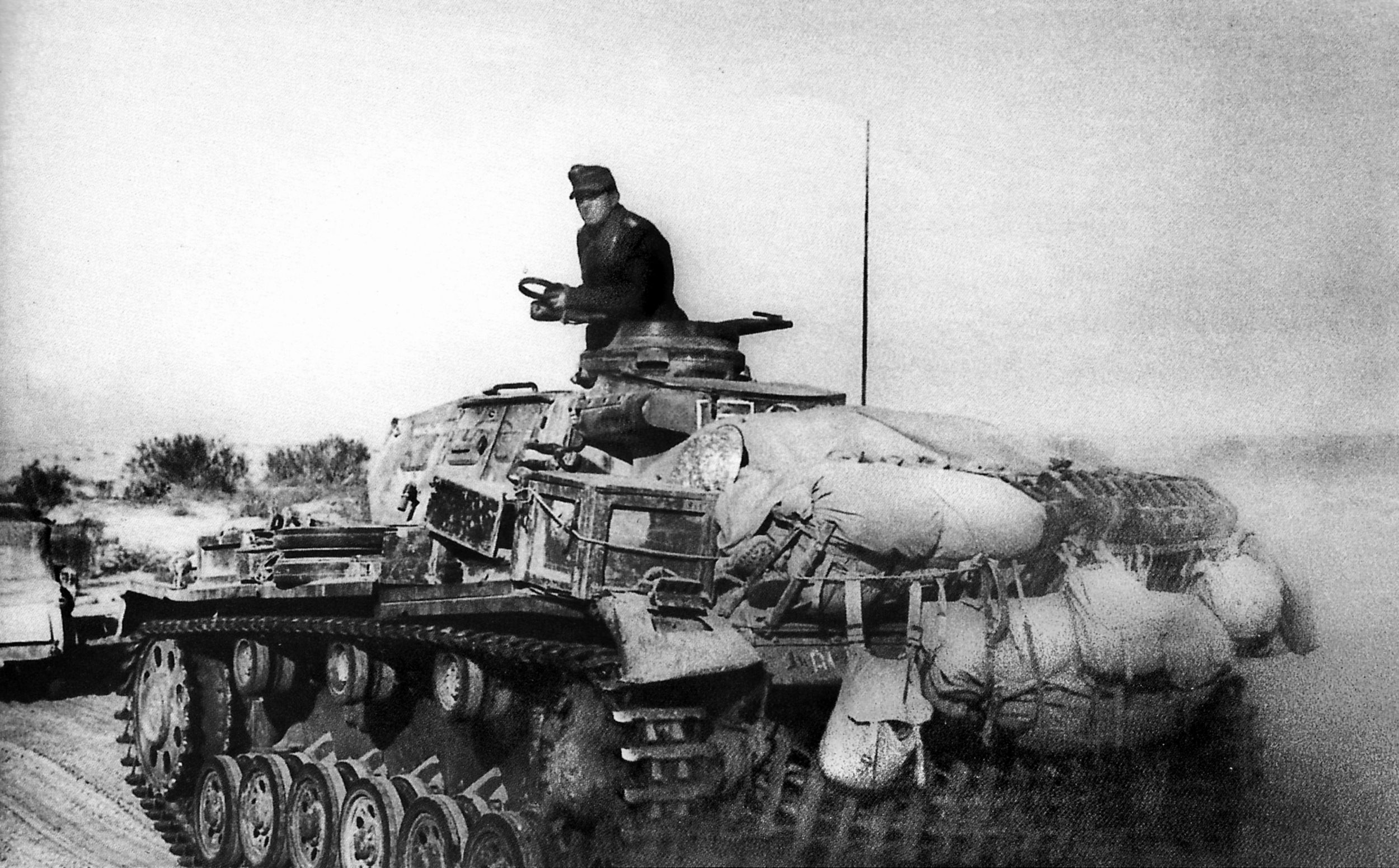

The first German units arrived in Tripoli on February 14, the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion and the 5th Panzer Regiment, part of the 5th Light Division, and Rommel ordered the port fully lit to speed the unloading. On the 15th, the German troops and their sand-painted vehicles paraded through Tripoli to buck up local morale, wearing uniforms designed for them by the Tropical Institute of the University of Hamburg. Aside from the uniforms, Rommel’s troops had no special training or equipment for the desert. They would have to learn the hard way.

Watching the parade was Rommel’s new aide, Lt. Heinz Werner Schmidt, who was impressed by the large number of tanks rolling past—until he noticed that one of the tanks clattering along in front of him was suffering the same fault in its tracks as a previous one he had noticed rumbling past. Rommel was trying to impress the Italians and fool the British by parading the same tanks two or three times to make them think he had thrice his actual numbers.

The numbers were pretty impressive—80 medium Mark III and Mark IV tanks and 70 Mark II light tanks—but Rommel had more deception in mind. He had his engineers turn Kubelwagen staff cars into dummy tanks with wood and canvas to further confuse the British. Knowing the British might bomb the decoys, Rommel told the commander of the fake tank unit: “I won’t hold it against you if you lose a few.”

At the parade, Schmidt was amused, but he was more concerned afterward, when the Italian tanks drove past. They got a better reception than the Germans. It was clear that the Italians were proud of their countrymen but barely tolerating the Germans. By day’s end, however, the 5th Panzer Regiment was on the road to Sirte, to prepare to face the British at El Agheila.

But while the Germans assembled for battle, their British opponents became disorganized and gave up the initiative as Field Marshal Sir Archibald Wavell, the commander-in-chief, was no longer focused on Libya, but on defending Greece. He had siphoned off the troops that had won the great victories, the Australian 6th Infantry Division and parts of the 7th Armored Division, to defend that nation. The rest of the tanks and vehicles of the 7th Armored—the famed “Desert Rats”—had been sent back to the workshops in Egypt desperately needing repairs. They had been replaced by two brigades of the 9th Australian Division, which lacked transport, was heavily equipped with captured Italian equipment—most of it actually reliable—and the determined leadership of Maj. Gen. Leslie “Ming the Merciless” Morshead, given that nickname for how his face scrunched up when concentrating on a problem. While unblooded, the Australian “Diggers” were well trained and heirs to a tradition of toughness that dated back to Gallipoli and the settlement of their nation.

The 3rd Indian Motorized Infantry Brigade benefited from long-serving Indian regular soldiers and officers and 200 trucks, but it had only half its allotment of Bren machine guns, and instead of the 42 Boys’ Anti-tank Rifles assigned to them, they had only 3.

Finally, the new 2nd Armored Division’s tanks and guns were mostly a hasty assemblage of outdated captured Italian equipment. The division’s 3rd Armored Brigade deployed 200 tanks, but two-thirds of them were light tanks, and the one regiment of medium cruiser tanks had only 23 “runners,” mostly Italian M-13s, which had already proved their inferiority in earlier battles. Some only mounted machine guns instead of 47mm cannon.

The entire force lacked signaling equipment, artillery, air support, and transport, which forced the British to rely on static dumps scattered around the Libyan desert to keep the men fed, fueled, and armed.

The British also suffered from weak leadership. The man who had led the desert triumph, Gen. Sir Richard O’Connor, had been sent back to Egypt to recover from his ulcer. In his place was Lt. Gen. Philip Neame, who held a Victoria Cross earned in the Great War and had gained a gold medal in shooting in the 1924 Paris Olympics, the only British or Commonwealth soldier to hold such a double distinction. He was an able man but nowhere near as skilled in mobile warfare as the brilliant O’Connor.

None of this seemed to matter to the British, though. Wavell’s intelligence, aware of the arrival of German troops in North Africa, did not believe they could be assembled, equipped, trained for desert fighting, and unleashed before April at the earliest. That would give Wavell time to prepare his men, deliver reinforcements, and bring up his own supplies.

But Rommel ignored Wavell’s timetables. He also ignored Hitler’s directives. The German plan for North Africa, Operation Sunflower (Sonnenblume), called for Rommel to maintain an active defense of Tripoli and its environs so as not to drain scarce German resources from the upcoming invasion of Russia.

Instead, Rommel prepared an offensive, determined to drive the British back into Egypt. He personally oversaw the measures, studying the desert hills and wadis from his Fieseler Storch reconnaissance plane and hustling, encouraging, and sometimes bullying his men to move troops, guns, vehicles, and supplies forward.

The efforts paid off on February 20, when a Marmon-Herrington armored car commanded by Corp. Harry Short of the King’s Dragoon Guards of the 2nd Armored Division was on a patrol led by Lt. Bill Williams (who would go on to become Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s chief intelligence officer), spotted an unusually heavy eight-wheeled armored car heading toward them.

The two armored cars raced past each other, skidded to a halt, and Short recognized the interloper’s design and crew caps as being of German manufacture. “My God! Weren’t those Germans?” Short yelled before the two vehicles exchanged fire and then raced back to their bases to report spotting the enemy.

Four days later, the battle heated up when a dawn British patrol at the abandoned Agheila fort found seven German tanks, three armored cars, and a section of troops on motorcycles waiting for them. The Germans shot up the lead armored car, wounding one man and taking two men as prisoners. Ten minutes later the Germans were riding off victorious with more armored cars blasted, POWs in hand, and a British staff car wrecked.

The tentative moves continued as March began. Rommel ordered Maj. Gen. Johannes Streich, commanding the 5th Light Division, to place minefields to prevent further British advances on Tripoli. By now, Rommel had 37,000 Italian and 9,300 German troops under his command. Most importantly, the Luftwaffe’s X. Fliegerkorps (10th Air Corps) had arrived in Sicily from Europe. Based in Sicily and Libya under Maj. Gen. Stefan Fröhlich, part of Fliegerführer Afrika’s mission was to support Rommel with 50 Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers as flying artillery and 20 Messerschmitt Me-110 twin-engine fighters as escorts. They were backed by the Italian Regia Aeronautica’s 90 fighters, 10 dive bombers, and 28 medium bombers, and while the Italian Army had suffered a bad reputation so far, nobody questioned the engineering of its aircraft or the courage of its airmen.

Rommel was pleased with how his men were training hard and adapting to the ghastly desert climate. The North African desert that Rommel and his men would fight in for the next two years was an incredible theater of war, stretching 1,200 miles from the River Nile to Tunisia and 1,000 miles from the Mediterranean to the southern edge of the scrubland. The western part of Libya was Tripolitania, dominated by the colonial capital of Tripoli, while the eastern half, Cyrenaica, was centered on the magnificent natural harbor and otherwise unmemorable town of Tobruk. Inland were endless sand seas and marshes like the Qattara Depression near El Alamein, across the Egyptian frontier. Near the coast were rugged escarpments difficult even for tracked vehicles. The only paved road was the Via Balbia, an Italian-built road that followed the seacoast. Inland, trails and tracks connected occasional wells, Ottoman-era forts, and oases.

Across this land was human emptiness—no towns, villages, people, or even drinking water. Ubiquitous rodents, scorpions, vipers, and flies were the only life. In summer it could become too hot to fight, especially in armored vehicles. German propaganda cameramen would make a great show of filming tankers frying eggs on panzer hulls but not revealing that the hull section had been doused in paraffin. At night, however, men had to wear overcoats as temperatures could drop 60 degrees.

Historian John Strawson noted that the Afrika Korps men expected to find endless soft sand. Instead they found “vast stretches of hard sand and of stony ground riddled with black basaltic slabs; there were bony ridges and ribbed escarpments and deep depressions; there were flat pans which held water after the rains…. There were wadi-fed flats which sprang overnight into flowery glory in spring; there were endless undulated sand and gravel dunes whose crests marched in rhythm, like waves at seas.” Rommel himself would compare desert fighting to sea warfare, regarding his panzers as battleships and ground merely as waves, possession of which was unimportant. What mattered was destroying the enemy’s army, something he grasped immediately while his opponents did not.

Heavy sandstorms that raced along as quickly as 90mph clogged rifle breeches, filled nostrils, buried food and equipment, and inflamed eyes. In winter, rain turned the dust-like sand into mud.

Water was the most precious item in the desert. In a 1942 battle, the Germans required three quarts per day per soldier, four quarts for each truck, and eight quarts for every tank. Both sides struggled to stay hydrated, drawing their drinking water from desert wells called “birs” and saving the stuff by washing clothes in sand and gasoline. The Germans had a superior water and gasoline pannier, while the British ones leaked. Very quickly the British started seizing captured German Einheits-Kanisters, and both British and American factories produced them under the name the British troops gave them: “jerrican.” They are being used in modern production forms to this day.

The jerrican was standard German army issue, but desert training was not. Rommel’s men had to add air and oil filters to their vehicles, adjust their carburetors to accept the lower-grade gasoline the Italians were providing, and even reorganize field ration packs to increase the amount of vegetables.

While this went on, Fliegerkorps 10 got down to business, hammering the British defenders of the King’s Dragoon Guards and the Tower Hamlets Rifles. Neither outfit was used to the Luftwaffe’s offensive style. The latter battalion’s officers were enthusiastic weekend soldiers, one of whom traveled with a bell-tent, carpet, and tin bath. The enlisted men were made up of London Cockneys, who were greatly worried about their East End families who were being bombed nightly by the Luftwaffe. Facing other Luftwaffe planes in North Africa, the Tower Hamlets men treated the incoming Stukas to both determined machine-gun fire and colorful East End invective.

Meanwhile, Rommel flew back to Berlin on March 21 to report on his progress, explain his plans, and receive the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves from Hitler for his feats in France. At the briefing with Army Chief of Staff General Walther von Brauchitsch and General Franz von Halder, Rommel was told to limit his offensive activity. Germany was about to invade the Soviet Union, and the North African war was to be a sideshow. However, the best defense was a good offense, and Rommel was ordered to take Agedabia, a hamlet beyond the British lines at El Agheila, and possibly Benghazi, and advance no further. Lengthening supply lines of an offensive would be intolerable. More importantly, Rommel was to wait until his second panzer unit, the 15th Panzer Division, had arrived in Libya and been acclimated before attacking.

Rommel protested and reportedly called Halder a bloody fool and asked him what he had ever done in war except sit on his backside in an office chair. Rommel flew back to Africa on March 23, and chose to attack anyway.

On March 24, Winston Churchill reacted to the sparring in the North African desert by sending Wavell a telegram that read, “I presume you are only waiting for the tortoise to stick his head out far enough before chopping it off.”

On March 31, Rommel answered Churchill’s telegram by unleashing the 5th Light Division against the 1st Tower Hamlets Rifles, hurling tanks and armored cars against their positions on the appropriately named Cemetery Hill and quickly pushing them back with sheer force amid 100-degree heat. With this done, the 5th Panzer Regiment stormed forward and met the 25-pounder guns of the 104th Royal Horse Artillery positioned behind the hill, firing over open sights. The Germans called down Stukas, but the British held the ground.

However, Rommel had already made a personal reconnaissance of the area in his Storch airplane and spotted an alternate attack route through the sand dunes along the coast. At 4:30 p.m., Streich led a battle group of tanks and infantry centered around Lt. Col. Gustav Ponath’s 8th Machine-Gun Battalion around the Tower Hamlets Rifles, broke through, and rolled up the British defenses.

However, the British had foreseen this, and the local commander called for the 6th Royal Tank Regiment (RTR) stationed in the rear to counterattack by night. The request went to Maj. Gen. Michael D. Gambier-Parry, commanding the 2nd Armored, and he vetoed it on the rational grounds that a night tank attack would be a disaster. Ironically, the 7th Armored Division, which his unit had replaced, specialized in night tank attacks. He chose to trade space for time and withdrew.

But Rommel had no appetite for a night tank attack, either, and he used the night hours to bring up troops, ammunition, and supplies. His offensive resumed on April 2, with his tanks and motorized infantry rolling up the Via Balbia, headed for Agedabia, 60 miles away. They ran into some 6th RTR cruiser tanks on their southern flanks and quickly destroyed seven of them and captured five more. By nightfall, the 5th Light was in Agedabia, one of a number of villages scattered the length of the Via Balbia.

That was as far as they were supposed to go under the orders given to Rommel. However, with 800 British POWs in the bag, Rommel sensed a complete victory. He took another calculated gamble, maintaining the offensive and splitting his forces into three columns. If the British had a concentrated armored force nearby, they could have destroyed him in detail, but the nearest such unit was an Australian brigade at Benghazi.

“One cannot permit unique opportunities to slip by for the sake of trifles,” Rommel later wrote.

Rommel sent his 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion on its three-man motorcycles with the Brescia Infantry Division on its left to Soluch and Ghemines. In the center, a column of tanks and motorized troops from the 5th Light and Ariete Divisions under the 5th Panzer Regiment’s Colonel Friedrich Olbrich would head across the central Cyrenaican tracks for the trail junctions of Antelat and Msus. On the right, the Ariete Division’s reconnaissance battalion and the German 8th Machine-Gun Battalion, under Col. Graf von Schwerin (who would later command the tough 116th Panzer Division in the Battle of the Bulge), would head at top speed across other tracks to cut off the base of the thumb of the Cyrenaican peninsula. Finally, the rest of the Afrika Korps and the Italian 10th Corps would follow along the coast road.

Most of Rommel’s columns would meet up at the track junction at Mechili, an oasis guarded by an Ottoman-era fort, which was also the largest British supply dump west of Tobruk with vast amounts of fuel stored in underground tanks. If Rommel captured the valuable stores, he would be able to keep driving forward. If not, his troops would be trapped in the barren desert.

Rommel’s plan was daring and simple. His mobile troops would drive across the Libyan desert toward Tobruk and cut off the British troops from behind. Italian General Zamboni protested, saying the desert route was a death trap. To prove him wrong, Rommel hopped into a staff car with two aides and drove along the track.

So the orders were cut, and the troops and vehicles roared off. The British withdrew, except for some cruiser tanks of 5th Royal Tank Regiment, which skirmished unsuccessfully with the 2nd Battalion, 5th Panzer Regiment, losing seven tanks for three panzers.

But logistics stopped the Germans where British shells could not. The Afrika Korps ran out of gasoline. Streich told Rommel that it would take at least four days to maintain the offensive. Rommel ordered all of 5th Light’s trucks and light vehicles to be unloaded where they were and sent back to the divisional fuel dump at Arco dei Fileni for gasoline, rations, and ammunition. For 24 hours much of the Afrika Korps was immobilized in the desert, potentially open to a devastating counterattack. It never came. Right after Agedabia fell, Wavell, aware of his shortage of troops and increasingly worried, flew to Neame’s headquarters at Barce, intending to replace the seemingly-hapless field commander with O’Connor, the victor of the earlier desert campaign, now recovered from his stomach ulcer.

Neame told Wavell that he had ordered 2nd Armored to move to an agreed deployment area near Antelat to cover routes to Benghazi or Mechili. Wavell countermanded that order, still convinced that Rommel did not have enough troops to take all of Cyrenaica. Benghazi had to be the only objective. The order was sent at 9 p.m., but Gambier-Parry did not receive it until 2:30 the following morning. By then, 2nd Armored’s vehicles were scattered, short of gasoline, and breaking down. The infantry was down to half strength.

Closer to the scene, Gambier-Parry figured the only thing he could do was disobey the order and regroup at Sceleidima. This habit of British generals regarding orders as suggestions to be digested rather than commands to be obeyed would continue through the North African campaign, resulting in many British defeats.

Next, O’Connor persuaded Wavell to leave Neame in charge. The quiet Anglo-Irishman could not “pretend I was happy at the thought of taking over command in the middle of a battle which was already lost.” O’Connor suggested that he function as an adviser to Neame. Wavell agreed. O’Connor would later describe it as “the worst proposal he had ever made.”

Wavell instructed Neame to fall back on a position near Benghazi if he was pressed and gave him permission to evacuate the city. The British simply lacked a powerful maneuver force that could counterattack the Afrika Korps. The troops who could do so were in Greece.

On the evening of April 3, Rommel drove to the northern flank, visiting the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion, and met with the battalion’s commander, Lt. Col. Baron Irnfried von Wechmar, who had a surprise for Rommel—an Italian priest who had slipped out of Benghazi to inform his countrymen and the Germans that the British were feverishly working to abandon the port.

Rommel changed the north column’s orders, telling Wechmar to drive straight for Benghazi, adding the reward of authorizing Wechmar to represent the Reich in the Benghazi victory parade.

Wechmar did so immediately, sending his scout cars, motorcycles, and trucks roaring north toward the city. In Benghazi, Neame ordered the demolition plans executed, and 4,000 tons of captured Italian ammunition exploded. By dawn, the harbor was an appalling mess of wrecked ships and harbor vessels. But Wechmar’s vehicles were in the city receiving a rapturous welcome from the city’s residents—the much-conquered Benghazi citizens greeted all their invaders warmly.

Meanwhile, Rommel headed back to his tactical headquarters to find an unexpected visitor, his nominal Italian superior, Gen. Italo Gariboldi, who commanded all Axis forces in North Africa. Gariboldi was furious with Rommel’s aggressive actions and violations of orders from Berlin—supported by Rome—which were unconventional and could easily lead to disaster. Gariboldi worried about Rommel’s flanks and supplies. As Rommel’s superior, he could halt Rommel dead in his tracks. Any further offensives had to be approved by the Italian Comando Supremo in Rome. Rommel flatly refused to obey any of Gariboldi’s orders and strictures.

Gariboldi started off by saying, “I am very displeased…”

Rommel cut Gariboldi off, saying, “I’m one up on you. I’m furious.”

As the two generals exploded at each other in harsher terms, a signals officer turned up with a message from Hitler—the one authority that nobody, German or Italian, could argue with. His reaction to Rommel’s offensive moves had been immediate and enthusiastic, and the Fuehrer, with Mussolini’s support, was now granting Rommel freedom of action in North Africa.

Rommel’s offensive had appealed to Hitler’s desire for unexpected, violent, and hard-driving attacks that rocked his foreign enemies back on their heels and annoyed his domestic detractors even more. The former lance-corporal enjoyed humiliating and berating generals. Just as important, victorious generals were good propaganda, and Hitler often saw battles, campaigns, and even military technology, purely in terms of their value as such. Rommel was good press and Hitler wanted more.

A livid Gariboldi turned on his heels and strode out of the room.

A buoyant Rommel wrote his wife that evening, “Dearest Lu: We’ve been attacking since the 31st with dazzling success. There’ll be consternation amongst our masters in Tripoli and Rome, perhaps in Berlin, too. I took the risk against all orders and instructions because the opportunity seemed favorable…We’ve already reached our first objective, which we weren’t supposed to get to until the end of May. The British are falling over each other to get away…. You will understand that I can’t sleep for happiness….”

On April 4, Rommel spent the morning harrying the 5th Light Division’s supply officers to resupply his tanks and ordering the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion, once finished with securing Benghazi, to head directly east for Mechili while the Brescia Division would tramp up the Via Balbia, suffering in the intense heat.

At Msus, a Free French motorized battalion had just arrived to guard the supply depot and saw tanks approaching. Assuming they were Rommel’s panzers, the Frenchmen blew the underground fuel dumps, and thousands of gallons of gasoline exploded in a spectacular ball of fire. The approaching tankers of the British 5th Royal Tank Regiment were not impressed. They needed the fuel to reach Mechili. They were down to 9 cruiser and 14 light tanks. As they clattered along to Mechili, more vehicles dropped out, and the survivors were refueled from the derelicts. By nightfall, the 5th RTR was down to eight tanks. The 6th RTR was in worse shape, down to two tanks.

In the face of Rommel’s drive, the British seemed both hapless and hopeless. Neame and O’Connor moved their headquarters from Barce to Maraua but could not stay in touch with their own men. The only capable leadership seemed to be Morshead, who kept his head and his Australian troops together.

By day’s end, Rommel’s 5th Panzer Regiment had occupied the village of Ben Gania, while the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion ran into three companies of the 2/13th Australian Battalion and a company of machine gunners from the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers holding the pass at Er Regima. The Germans pushed up the road but lost two tanks. With help from Ponath’s 8th Machine Gun Battalion, they forced the Australian-British force to withdraw as darkness fell.

The competing leadership styles were clearly visible. Rommel seemed everywhere at once, scouting the terrain and his troops’ movements from his airplane, visiting with frontline commanders and issuing orders on the spot, urging supply and transportation officers to keep vehicles moving. Meanwhile, Neame never left his headquarters at Barce, 50 miles northeast of Benghazi. He was an unseen figure to his troops, who called the conflicting orders and hasty withdrawals the “Tobruk Derby” or “Benghazi Handicap.”

On April 5, however, the Germans also began to suffer from confusion. The Ariete Division fell behind schedule. Olbricht’s 5th Panzer Regiment could not reach Msus on time, either. Fuel shortages and maintenance problems were the reason. German and Italian columns were strung over 20 and 30 miles of desert as vehicles broke down in the gritty terrain. Rommel sent his intelligence officer, Captain Baudissin, to fly over the battlefield in a Heinkel He-111 to find out what was going on, but he was shot down and captured.

Rommel once again imposed his formidable presence on his men. When Streich asked his boss for permission to halt the drive for four days for maintenance and resupply, Rommel snapped that the advance would continue.

“Impossible,” Streich answered.

“I couldn’t care less,” Rommel retorted. He called the request to halt a “ridiculous pretext” and told Streich to take the fuel from nonessential vehicles, which could wait until the tanker trucks arrived from the rear. The advance continued.

At 2 p.m., Rommel got word from the Luftwaffe that the British had abandoned the Mechili junction. He ordered Schwerin: “Mechili clear of enemy. Make for it. Drive fast. Rommel.” He flew off to take personal command of the leading 8th Machine Gun Battalion, reaching the column by late afternoon. He personally led their drive through the night, keeping their headlights on to spot minefields and wrecked vehicles in their path, ignoring the possibility of Royal Air Force attack.

At 6:30 a.m. on April 6, Rommel was 15 miles south of the old Turkish fort, but with only his machine gunners at hand. There was no sign of Streich and his tanks. Rommel dispatched aides to locate his division commander and found him miles from where he was supposed to be. Rommel raced back to find Streich and ordered him to attack Mechili at 3 p.m.

Streich refused. His division was scattered across 100 miles of desert, most of its vehicles with overheated engines or no gasoline. Rommel flew into a rage and called Streich a coward.

The 5th Light Division’s commander ripped his Knight’s Cross from his neck and roared, “Withdraw that remark, or I’ll throw this at your feet!” For once, Rommel realized he had gone too far and offered a halfhearted apology.

While the two generals argued, the 5th Light Division tried to sort out its difficulties and maintain its advance, finally taking the burned-out wreckage of Msus. But it had 85 miles to go before reaching Mechili, and all the fuel tanks at Msus had been destroyed.

The British were having their nightmares, too. Neame spent most of April 6 looking for Gambier-Parry in the Got Derva area east of Charruba, not knowing that the 2nd Armored Division’s commander had withdrawn to Mechili. It was clear that the headquarters of the Western Desert Force—now called the Cyrenaica Command—had to run for it. Neame offered a seat in his staff car to O’Connor, who lacked transport, let alone an official job, while sending his chief of staff, Brigadier John Harding, on separately with other officers. The two generals hopped into Neame’s Lincoln Zephyr staff car with Brigadier John Combe, another hero of the original campaign, and headed east with Neame driving. The regular driver was exhausted. Behind them was another staff car full of officers, including Neame’s aide-de-camp, Captain The Earl of Ranfurly.

As night fell, Neame and O’Connor took a wrong turn heading too far north. O’Connor was certain such was the case and said so three times to Neame, who said that the road was very twisty and the lack of traffic was because they had passed it all. As the night wore on, the driver recovered and took the wheel again while Neame and O’Connor slept in the back.

The officers came up to a long, slow-moving line of trucks and other vehicles. They started to overtake the column, but had to halt. Lord Ranfurly heard the strangers’ crews talking in a foreign language and asked his driver who they were.

“I expect it’s some of them bloody Cypriot drivers, sir!” the driver said, presuming they were members of transport companies drawn from the British Mediterranean island colony. Ranfurly climbed out and walked to Neame’s car intending to order the Cypriots to move along, but instead felt a submachine gun being shoved in his ribs by an Afrika Korps soldier. The soldier moved down the staff cars, and Ranfurly and Combe warned the two generals to get down on the floor so they might be able to slip out and crawl away.

It was too late. A posse of Germans descended on the two cars and took the whole lot prisoner—the top British field general in Libya, Neame, and perhaps Britain’s finest field commander of the entire war, O’Connor. Both would go in the bag for three years until they escaped Italian captivity and returned to British lines.

O’Connor would never cease to blame both himself and Neame for their capture—Neame for taking the wrong road, and himself for not insisting they take the right direction. Still, O’Connor wrote later: “I must confess that the possibility of being on the wrong track did not really worry me very much, as I felt that we should strike the Derna-Tobruk road rather further west than Martuba, and I had no idea whatever that there was any chance of meeting a German force in that area.”

O’Connor’s capture was a disaster of the first order, and the entire British leadership took it heavily. Wavell suggested to London that an offer be made to exchange six captured Italian generals for O’Connor, but the chiefs of staff were reluctant to do so. Wavell’s successor, Field Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck, said he was willing to trade as much as £20,000 for O’Connor.

Neither general quite fully recovered from the capture despite their courageous escape from captivity. After Neame returned to Allied hands in 1943, he was interviewed by General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Field Marshal Harold Alexander, and Prime Minister Churchill on his experiences but was offered no further wartime jobs. He became lieutenant governor of Guernsey after the war, gained a knighthood in 1946, and died in 1978. However, his son, also named Philip Neame, commanded D Company, 2nd Battalion, the Parachute Regiment, in the Falklands War, and rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel, commanding 10th Battalion, the Parachute Regiment.

O’Connor fared better. He was given command of the 8th Corps in the invasion of France, leading it in bloody and fairly successful fighting in Normandy and Holland, but was sacked by Montgomery in November 1944 for not being “ruthless enough” on American subordinates. He then served in India, coordinating supplies and logistics for the drive in Burma, and as aide-de-camp to King George VI until retiring from the army in 1948 after another row with the prickly Montgomery. Probably to soften the blow, he was installed as a Knight Grand Cross of the Bath, and in 1971, created Knight of the Thistle. Yet his tremendous victory over the Italians was never remembered properly. The force was called “Wavell’s 30,000” in popular press and histories, and he missed the chance to use his flexibility, superb tactical and operational skills, and deep understanding of warfare against Rommel and other worthy opponents.

While O’Connor and Neame went in the bag, one future top British leader narrowly avoided it, John Harding, who arrived at Tmimi on the morning of April 7 to discover that his bosses had vanished, he was the senior officer in the area, and the British position was collapsing.

Harding, a superb planner and future field marshal, moved immediately, working with Morshead to form a line of Australians from the 9th Division’s 18th and 24th Brigades to build up the defenses of Tobruk, restoring and strengthening the old Italian fortifications that had been damaged in the 1941 British offensive.

April 7 was no improvement for the German drive, either. The Italians, already behind schedule, fell further behind when they ran out of fuel. Rommel ordered all available fuel—35 cans—rounded up for them. Olbricht’s 5th Panzer Regiment got lost amid sandstorms in the empty desert, and Rommel flew off in his Storch to find them. He spotted a column and ordered the pilot to swoop down beside it, figuring it was 5th Panzer—they had even laid out a cross upon which to land. But it was actually a British column. The cross was meant to fool Rommel, and they greeted him with machine-gun fire, which hit the plane but did not wound the occupants.

It was not until the night of April 7, that Rommel’s forces were assembled before Mechili’s defenders, which consisted of elements of the 2nd Armored Division and its commander, Gambier-Parry himself. The British tried to extricate their troops but found themselves surrounded. Rommel wrote to Lucie that he was hoping for a modern-style Cannae.

At dawn, Rommel sent an officer to ask Gambier-Parry for his surrender, and the Briton refused. At 6 a.m., Streich opened the attack while Rommel gave overall direction from his Storch. Shortly after takeoff, Rommel’s plane flew over an Italian engineer battalion at a height of 150 feet. The astonished Italians opened fire on Rommel with everything they had but missed the Storch. “It did not speak well for Italian marksmanship,” Rommel wrote later. He flew to 3,000 feet to observe the battle better.

Rommel saw no sign of Olbrich’s force, which he presumed was still coming up, but did spot one of his 88mm guns a mile or two just west of the British. Rommel decided to land there to check on the advance. As the plane taxied to a sand hill, it piled up and became a write-off.

The gun commander reported that his gun had been attacked and shot up by tanks while arriving the previous day, and he was the only Axis unit in that neighborhood. Rommel observed an approaching dust cloud and asked the gunner to open fire on these advancing British vehicles, interested in the air crash. The gunner said the man who had gone off in their truck had taken the firing pin. However, they had another truck at hand. Rommel later wrote, “It was obviously high time for us to be off if we were not to find our way to Canada!” That nation was the final destination for most German POWs at the time.

All hands decamped, and Rommel found his way back to Afrika Korps headquarters. Once there, he headed out again to find his advancing troops and check on the attack. After this, he would not try to command battles from the sky.

Meanwhile, Streich’s attack had paid off. Not only was the old Turkish fort taken intact, so were the critical fuel dumps along with 3,000 British prisoners, including Gambier-Parry and Brigadier Edward Vaughan of the 3rd Indian Motorized Brigade.

Gambier-Parry was caught in his armored command vehicle (ACV), found on a slight rise along with two others, and as Lieutenant Schmidt and other senior Germans were looking them over, Rommel landed on the fort’s landing strip, dodging wrecked Italian and British aircraft. He strolled over to an ACV and inspected its immense tires, wireless sets, and desks for paperwork. He promptly seized two of them, calling them “Mammoths” for their large size, to use as his mobile field headquarters vehicles. The two Mammoths were dubbed Max and Moritz for two characters in German children’s stories.

Rommel also briefly interviewed Gambier-Parry and his command team and then looked through their abandoned gear. One item fascinated Rommel, a large pair of sun-and-sand antigas goggles. He grinned, and said, “Booty. Permissible, I take it, even for a general.” He picked them up and adjusted the goggles over the gold-braided rim of his cap peak. They would stay there, except when in use, pretty much for the duration of his war in the desert and became symbolic of his image as the “Desert Fox.”

Another part of the desert war’s image was established that day as well. A severely wounded British officer asked Schwerin to get word to his wife in Alexandria that he was alive but captured. Schwrin promised to try, and sent a message “in the clear” over the British radio frequency to that effect. The British acknowledged the message and an hour later radioed back that the message had been delivered. The desert campaign was becoming, as Rommel would later write, a “war without hate.”

With Mechili and Gambier-Parry in hand, Rommel turned his POWs over to Italian troops and ordered Olbrich to refuel his panzers and follow von Schwerin’s light forces to Derna, a small town near the coast northwest of Tobruk, which had been specifically created by the Italians as a colonial settlement—modern homes and shops with electricity and running water. Most of these homes and shops had fallen victim to the earlier battles and Arab looting, but some were still intact.

The advance did not take long. By 6 p.m., Rommel himself was in the battered community, connecting with Ponath and the Brescia Division. Also on hand was Maj. Gen. Heinrich von Prittwitz und Gaffron, commander of the 15th Panzer Division, which had started unloading in Tripoli. Having an experienced major general on hand, Rommel put Prittwitz in charge of the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion, the 8th Machine Gun Battalion, and the 605th Anti-Tank Battalion, ordering him to take this combined arms group along the coast road and quickly drive the Australians out of Tobruk. Prittwitz was happy to do so, having been an energetic panzer commander in Poland and France. They charged down the Via Balbia and took more than 800 prisoners in their advance.

Both sides knew the importance of Tobruk, an otherwise unimpressive community of barely 4,000 people living in a few hundred white houses. Tobruk had the best natural harbor on the Libyan coast and a water distillation plant that produced 40,000 gallons per day. Churchill ordered Wavell on April 7 to defend Tobruk “to the death, without thought of surrender.” Wavell’s response was to fly to Tobruk on April 8 and put Maj. Gen. John Lavarack, commander of the 7th Australian Division, in charge of Neame’s old command, providing him with troops by land and sea.

The 7th Australians had originally been set to reinforce the defense in Greece and Crete. Nazi troops were storming into Greece and Yugoslavia, and British forces there were being evacuated. A coup in Iraq had put a pro-Axis government in power in that nation, central to Britain’s oil supply. Other British forces were struggling to clear out Italian East Africa, whose defenders were proving surprisingly tenacious. Rommel’s advance in Libya could not have come at a worse time for the British.

Wavell asked Lavarack if he could hold Tobruk, and the Australian replied that he could. Wavell then said, “Well, if you think you can, you’d better get on with it!”

Under Lavarack were his 7th Division and two brigades of Morshead’s 9th Australian Division, four artillery regiments with 4.5-inch howitzers, reliable 25-pounder field guns, the Northumberland Fusiliers with their machine-guns, two anti-tank regiments, 75 antiaircraft guns, 45 tanks, a squadron of RAF Hawker Hurricane fighters, and a total of 36,000 men.

Those were not Tobruk’s only defenses. With the formidable engineering ability that had been the hallmark of the Italian Army since the Roman legions, the Italians had created a 16-mile perimeter defense around the town with a series of 128 concrete posts in two rows along with tunnels, underground chambers, anti-tank ditches, barbed wire, firing pits, and trenches. Behind this Red Line stood the Blue Line, two miles closer to Tobruk, with pits for mortars.

But these impressive defenses had not held up the attacking 6th Australian Division’s assault on the port for long in 1941, and had not been much improved. In fact, some positions were damaged from the previous battles. Rommel was aware of this and also aware that the defending Australian-British force, like the Italians in 1941, was regrouping after a demoralizing series of defeats and retreats.

Rommel ordered Prittwitz to attack Tobruk on the morning of April 10, from the west, while the Brescia Division’s infantry and Trento Division’s artillery provided a diversionary attack to the southwest. Rommel ordered Streich and his armor to head there as well, but both Streich and Olbrich made protests. Their tanks needed maintenance. Rommel flew to Mechili and ordered Olbrich to get his panzers moving. Then Rommel raced back to Prittwitz’s area, arriving at dawn. Rommel found Prittwitz had driven through the night to catch up with his command and had gone to sleep. Rommel ordered Prittwitz out of his bedroll, saying Prittwitz was giving the British time to do another Dunkirk, and ordered him forward.

Amid this tale of exhausted Germans struggling to advance, one German leader was still moving. Ponath and his 8th Machine Gun Battalion were within 16 kilometers of Tobruk when they reached a bridge that spanned a wadi. As they raced for it, sappers of the Australian 2/3rd Field Engineer Company hit their detonators, blasting the bridge and stopping the machine gunners cold. British artillery and Northumberland Fusiliers machine guns opened fire, delaying the Germans long enough for Prittwitz to arrive with Schwerin’s armored cars. Prittwitz set the German example, personally leading a charge down the highway amid sandstorms. The British set three cars on fire, and Prittwitz was killed by a direct hit on his vehicle from a British anti-tank gun. With that, having lost three dead and 30 wounded, the Anglo-Australian force withdrew into the fortress, leaving behind the first German general to die in North Africa.

The attack was poorly organized and coordinated and was a mark against Rommel’s generalship. So was his continued disdain for supply. His tanks and vehicles kept outrunning their fuel trucks, and he ignored his junior officers’ requests to take time to refuel and repair battered vehicles. Instead, Rommel would berate those officers for not maintaining the pace of the offensive. He didn’t seem to have much sentimentality for his officers at all. After Prittwitz’s death, Rommel met again with Streich and Olbrich, who argued with Rommel over the pointless death of Prittwitz. Rommel just said, “We probably tried too much with too little. Anyhow, we are in a better position now.”

The meeting had more unpleasantness. When Streich’s two-car convoy came up for the conference, Rommel saw them through his binoculars, identified the vehicles as British, and ordered his escort to get their 20mm antiaircraft gun ready to tear them apart in case it was a British raiding group. It turned out to be Streich in captured cars, and Rommel shouted that Streich should never have followed Rommel in a British car—he might have been shot.

Streich coolly replied, “In that case, you would have managed to kill both your panzer division commanders in one day, Herr General.”

Rommel sent the 2nd Machine Gun Battalion to the Bardia roadblock to release Wechmar, who was to drive on to Bardia and seize that coastal town. A mixed force of infantry was to dash to Sollum and cut off British escape routes to Egypt. With that, the encirclement of Tobruk was complete, and it was time to attack the port. However, Rommel and the Afrika Korps lacked decent maps of the place. While the Italians had created the entire fortified complex, their cumbersome bureaucracy was having a hard time locating the original maps and blueprints.

No matter. On Good Friday, April 11, Rommel would attack. After three days of moving vehicles, men, and fuel forward, the Luftwaffe had finally set up landing strips close enough to the battlefield for the dreaded Stuka dive bombers to operate. Aware that Tobruk’s defenders were growing stronger every day and that he lacked hard information on the defenses, Rommel ordered Olbrich to attack blind. Olbrich objected, citing that his tanks were not battleworthy.

“You will attack nevertheless,” Rommel snapped, adding that he would personally join the assault.

Olbrich’s tanks and Ponath’s machine gunners moved up the dirt road from El Adem airfield, Tobruk’s landing strip, in the afternoon against the 2/13th and 2/17th Battalions of the Australian 20th Infantry Brigade, fighting their first battle. Ponath’s men went in first, expecting that the green Australians would flee and leave behind their nation’s excellent beer to drink.

Instead, the Australians greeted the Afrika Korps with heavy fire, and the 8th Machine Gun Battalion had to hit the dirt and summon tanks. About 10 of them came rumbling up, hurling shells against the Australian bunkers. The Australians, lacking antitank guns, could not shoot back. But they did not need to. The German tanks clattered up to the Italian-built anti-tank ditch and stopped.

A frustrated Olbrich ordered his tanks to turn east and drive parallel to the massive ditch and find a way in. Meanwhile, the British responded, sending five cruiser and eight light tanks of the 1st Royal Tank Regiment, part of the fortress reserve, to counterattack. The British and German tanks traded salvos across the anti-tank ditches and fortifications like warships on the high seas. The battle lasted for half an hour with both sides blasting holes in each other’s tanks. At that point, British heavy artillery opened fire on the Germans, and Olbrich decided he had had enough, leaving behind three blasted tanks and Ponath’s men, trapped in bare rock and scraping hollows. These Germans remained in place until nightfall, when Pioneers of the 200th Engineer Battalion reinforced them with explosives for a night attack to penetrate the defenses.

The Australians had not been idle. They put out aggressive patrols that spotted the pioneers, and the Diggers struck back in the dark, forcing the pioneers to abandon the project. The pioneers shuffled back to their lines in the dark while Australian troops laid additional mines before their positions.

At dawn, Ponath’s men were still in position, lying under the burning sun, thirsty, covered in flies, suffering from heat and Australian small-arms fire. The Luftwaffe added humor to the situation by dropping leaflets calling upon Australian troops to surrender by displaying “white handkerchiefs” on their rifles. The Australians were in no mood to give in, and nobody had any white hankies, anyway, so they used the leaflets as toilet paper.

Rommel had to face facts and take time for supplies and maintenance, but berated Streich, saying “Your Panzers did not give their best and left the infantry in the lurch!”

Streich answered, “The panzers would have reached their objective despite strong anti-tank fire, if the whole sector had not been protected by deep and well-protected anti-tank traps.” There weren’t any such traps, but there was an anti-tank ditch.

Rommel said Streich and Olbricht “lacked resolution” and ordered the 5th Light Division’s commander to attack Tobruk, saying, “I expect this attack to be made with the utmost resolution under your personal leadership.” Rommel’s aide, Heinz Werner Schmidt, would accompany the attack to make sure Rommel’s orders were carried out.

The attack went off at 6 p.m. on April 13, Easter Sunday, with Schmidt riding with Streich in the latter’s staff car. Behind rolled a tank that Streich would mount to lead the attack. The division commander held the only operational map the 5th Light had and used it to figure out where he was in the desert wasteland. Schmidt seemed to have a better grasp of the terrain than Streich but was reluctant to tell the general what to do until they took a wrong turn, came under British fire, and all hands leaped into the tank.

With that, the panzers finally rolled forward, running late because of Streich’s wrong turn, and headed west to their assault area.

Meanwhile, Ponath’s machine gunners and pioneers tried again, backed by a battalion of antiaircraft guns. In the darkness they finally were able to create a breach in the minefield and demolish the anti-tank ditch.

The Australians counterattacked with heavy fire, and a patrol under Lieutenant Austin “Mummy” Mackell of seven men went out to find the Germans. Among them was an immense sheep farming corporal named Jack Edmondson, who put two German machine guns out of action with his grenades and bayoneted an enemy soldier, suffering wounds in the stomach and throat. When Mackell’s bayonet got stuck in the body of one German and his legs were held by that man, another German attacked Mackell from behind. Mackell yelled for help. Edmondson ran over and killed three Germans, freeing Mackell and sending the Germans packing. Edmondson then stood up and collapsed. His buddies carried him to the rear, where he died upon arrival. His valor earned him Australia’s first Victoria Cross of the war. He was buried in the Tobruk Commonwealth War Cemetery.

Ponath and his men finally established a bridgehead beyond the antitank ditch, got behind strongpoint R33, and promptly unleashed machine-gun fire on the Australian positions as the pioneers expanded the gap for the tanks.

By 5 a.m., Olbrich’s panzers were finally on the right course and headed for the bridgehead. The defending Australians held their fire while Olbrich’s infantrymen unloaded from their trucks and half-tracks and the tanks stopped advancing to wait for Streich himself to catch up with them.

At that point, the Australians opened fire with everything they had, and everybody, even Streich and Schmidt, was pinned down, first by Australian small arms and machine guns and then by British artillery. Morshead ordered two tank squadrons to counterattack, and they did so with gusto, knocking out 16 of Olbrich’s 38 tanks. Streich and Olbrich ordered their tanks to withdraw, leaving Ponath’s men trapped.

Rommel was enraged. Later he would sack both Streich and Olbrich. He ordered another attack, this one not to take Tobruk but to save the surviving men of 8th Machine Gun Battalion. The only force available was the Italian Brescia Division. German troops wagged that the Italian army was the bravest in the world because its men fought with the ghastly weapons they were issued.

The Brescia Division tried, but British shells and Australian bullets stopped them. “The confusion was indescribable,” Rommel wrote later. “The division broke up in complete disorder, turned tail and streamed back in several directions.”

Rommel could not save Ponath’s battalion, which dug in amid the stony terrain lacking food, water, and ammunition. Ponath himself was twice wounded. The Australian troops and British tanks began to mop up the exhausted machine gunners, and the Germans began to surrender—except for one individual who dropped his hands, picked up a gun, and shot Lance-Sergeant Hulme. Other Aussies gunned down this individual.

Ponath was among the Germans who died. There were a number of them, including one who suggested that he lead a last charge with 60 survivors to break through the British defenses. But the second-in-command, Captain Bartsch, recognized the futility of the situation and surrendered as many men as he had under his command to an Australian major standing on the field. The two officers met face to face and saluted. The Digger reached into his vest to produce a cigarette case and gave one to the German saying, “Good fight.”

Rommel had some kind words for the 300 survivors of the battalion who reached German lines or had been left out of the engagement, too. He told them that they should not let their heads hang down; getting killed and losing battles was the destiny of soldiers. Sacrifices had to be made, the material and manpower losses would be made good, and Ponath himself would receive a posthumous Knight’s Cross for his courage, which spoke for the entire battalion, living or dead.

Rommel’s words cheered the men up and told them why things had gone wrong—the breakthrough was on too narrow a gap. The Afrika Korps would attack again and win again. The men believed their commander. They had good reason to. In a mere two weeks, his rampaging force of one German light armored division, an Italian armored division, and an Italian infantry division had driven the British from Tripoli to Tobruk, shattered their defenses, wiped out a British armored division and a motorized brigade, captured their supply dumps, and even bagged three top British generals—one of them quite likely the best British general of the entire war.

In doing so, Rommel had established himself as a flawed master of the desert battlefield, driving mechanized forces at high speed across the terrain, doing what seemed impossible despite shortages of supplies, troops, and gasoline. He was now the image of Germany’s ability to wage successful blitzkrieg war, down to the sun goggles he had “liberated” from a British command vehicle.

The German propaganda machine was quick to capitalize on this with Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels making sure that images of Rommel in his gritty jacket, sun goggles, peaked hat, and World War I Pour le Mérite around his throat, would be prominent in newsreels and in newspapers and magazines. Soon Rommel’s opponents would be respecting him and honoring him as well, including Winston Churchill himself. Privately the prime minister snarled, “Rommel! Rommel! Rommel! What else matters but beating that man! But publicly, he called Rommel “across the havoc of war, a very great general.”

The Australians on the other side of the Tobruk defenses on the evening of April 14, 1941, were experiencing a different epiphany. They had just delivered the first defeat to German ground forces in World War II. While Rommel would attack again in his efforts to seize Tobruk, these assaults would also fail, and the port would remain besieged in a desert version of Great War trench fighting for 242 days until New Zealand troops of the British Eighth Army broke the siege on December 7, 1941, a feat obscured by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the Russian counteroffensive at Moscow the same day.

The Germans had been stopped. This had never happened before. The captured men of 5th Panzer Regiment and 8th Machine Gun Battalion knew it, too. The Australians tried to make them comfortable as they herded them back to POW camps, offering them cigarettes and tea. Some were in tears, others devastated, a few defiant, threatening the Diggers, saying, “You will pay for this.”

But some simply did not realize what was going on. “I cannot understand you Australians,” a German told his captors. “In Poland, France, and Belgium, once the tanks got through the soldiers took it for granted that they were beaten. But you are like demons. The tanks break through and your infantry still keep fighting.”

The Germans had never encountered anyone as tough as the Australians and the British in their conquest of Europe. It was a rude awakening.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments