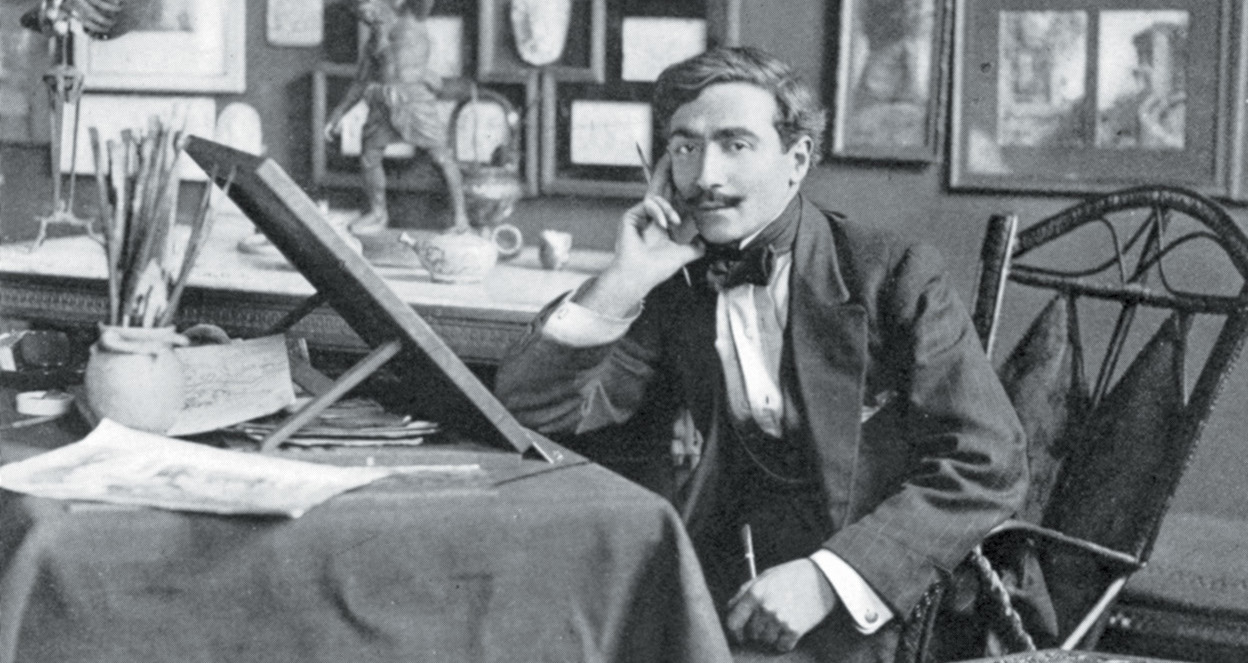

By Peter Harrington

In the annals of war photography, Roger Fenton stands with Mathew Brady, Alexander Gardener, and James Robertson as one of the pioneering spirits. His name is ever linked to the Crimean War. The work he did in that period built his reputation and sustained him until his death in August 1869.

Commissioned by the publishing company Agnew and Sons of Manchester, England, Fenton set sail on December 26, 1854, with the sole intention of compiling a photographic record of the “seat of the war” in the Crimea. This represented a large investment for Agnew’s, but they were hopeful of big returns from the sale of Fenton’s photographs. Although war photography was still in its infancy (some of the earliest images were taken during the Mexican War of the late 1840s), people saw its advantages over engravings and were eager to adopt it. Several weeks before Fenton’s departure, the British government had dispatched an official photographer, Richard Nicklin, with two soldiers to assist him, but they perished off the port of Balaklava when their ship, the Rip Van Winkle, sank during a hurricane that hit the coast of the Crimea in November.

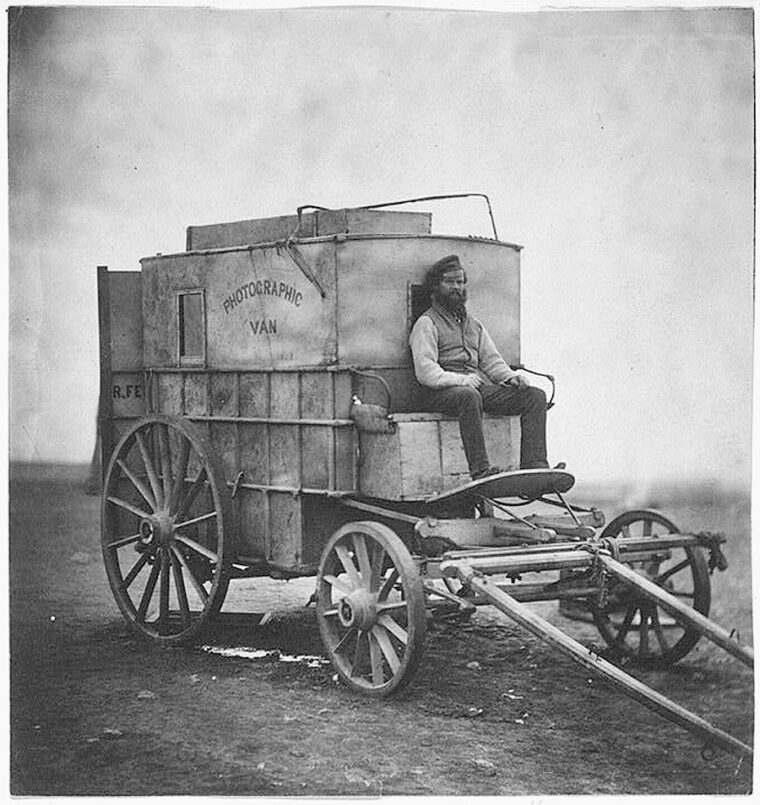

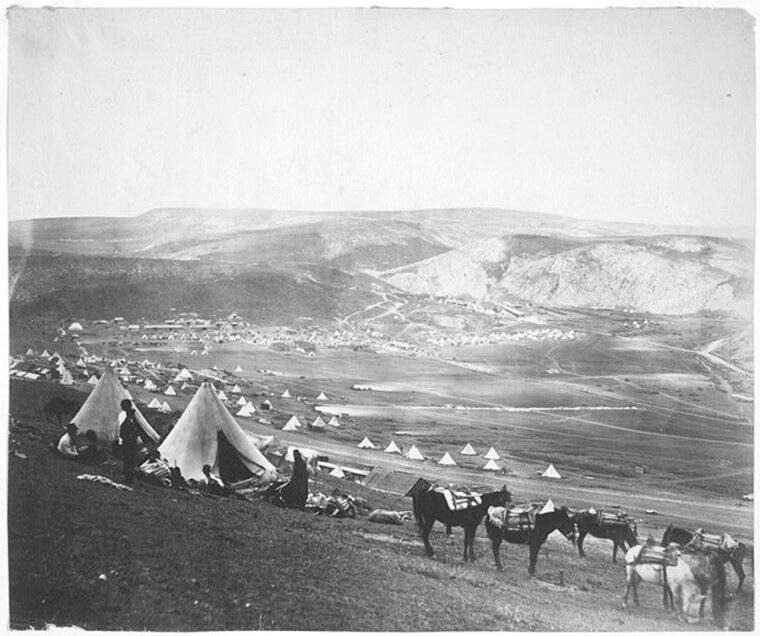

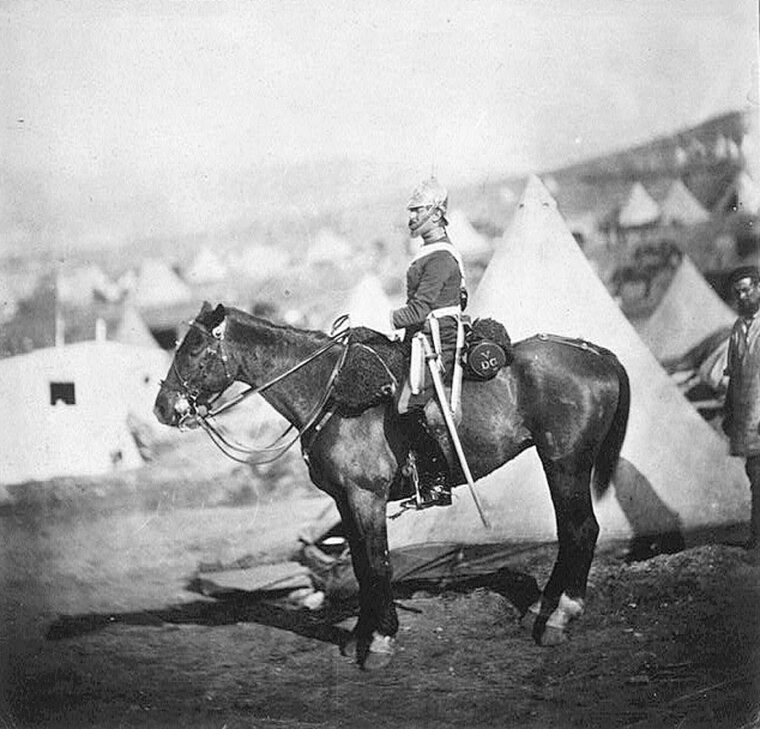

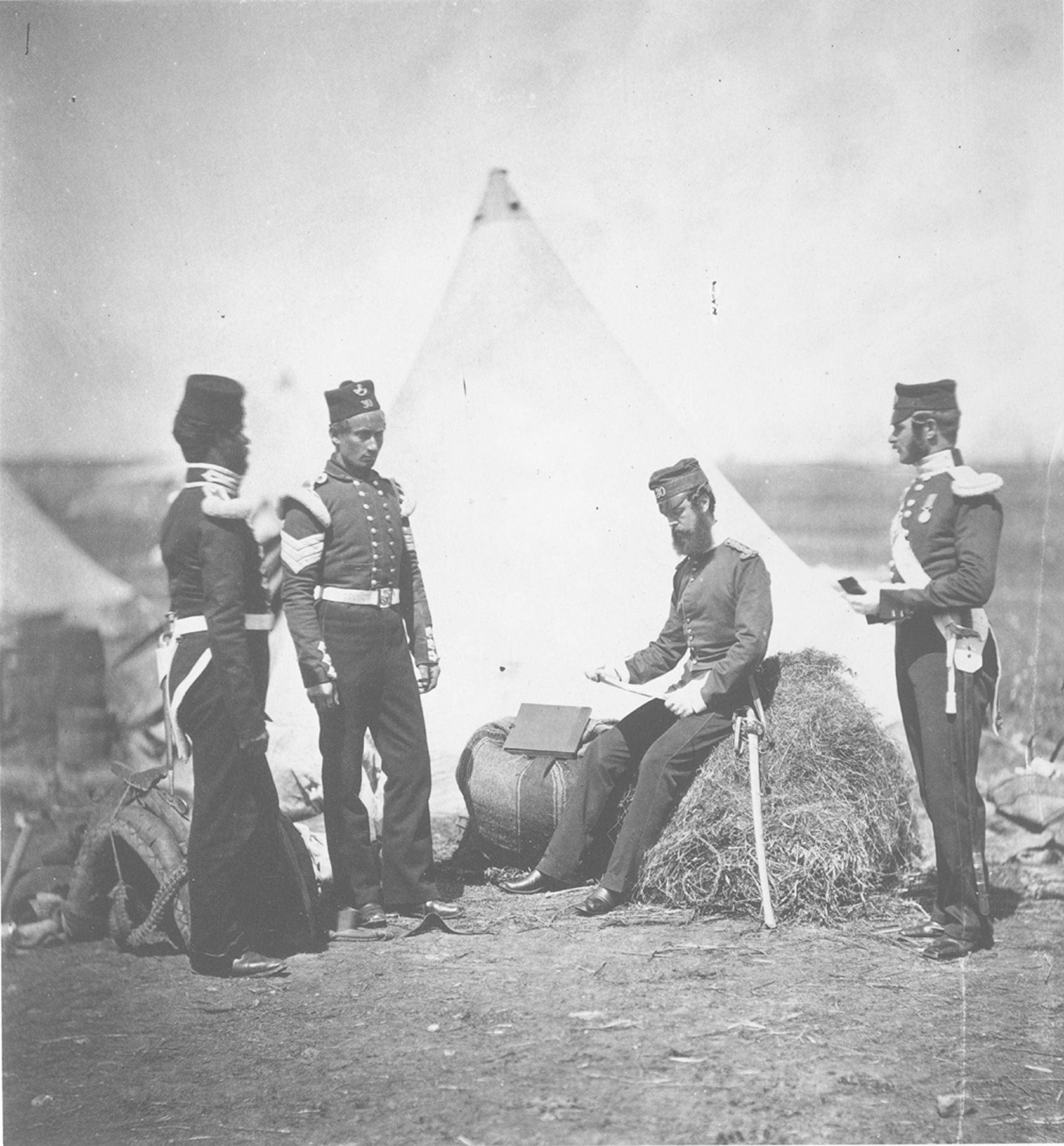

Upon his arrival at Balaklava aboard the Heckla on March 8, 1855, along with his two assistants and his horse-drawn photographer’s van, Fenton presented his letters of introduction, including one from Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband. He quickly became popular with the various British commanders and officers who sat for his photographic portraits. Colonel Edward Cooper Hodge noted in his diary of April 28, 1855: “I have had a sketch [photograph] made of my hut and camp by Mr. Fenton, the photographer to the British Museum, who is out here. It is of course very correct, but it should be coloured to give you a good idea of the beauty of the rocks and hills.” These photographs were sent to the soldier’s mother two days later and were among the first of Fenton’s photographs to reach England.

Fenton used the wet cullodian process by which a glass plate was first dipped in a sensitizing bath. While still wet, it was exposed in a large, bulky box camera, removed, and developed. The weather conditions, particularly during the summer in the Crimea, meant it was impossible to work after 10 am owing to heat, dust, and flies. All the developing work was done in Fenton’s photographic van, which had been converted from an old wine merchant’s wagon. This traveling “darkroom” also contained 700 glass plates and five cameras, all stored in 36 chests, along with tanks of water, tools, stoves for cooking, and his own supplies of tinned food.

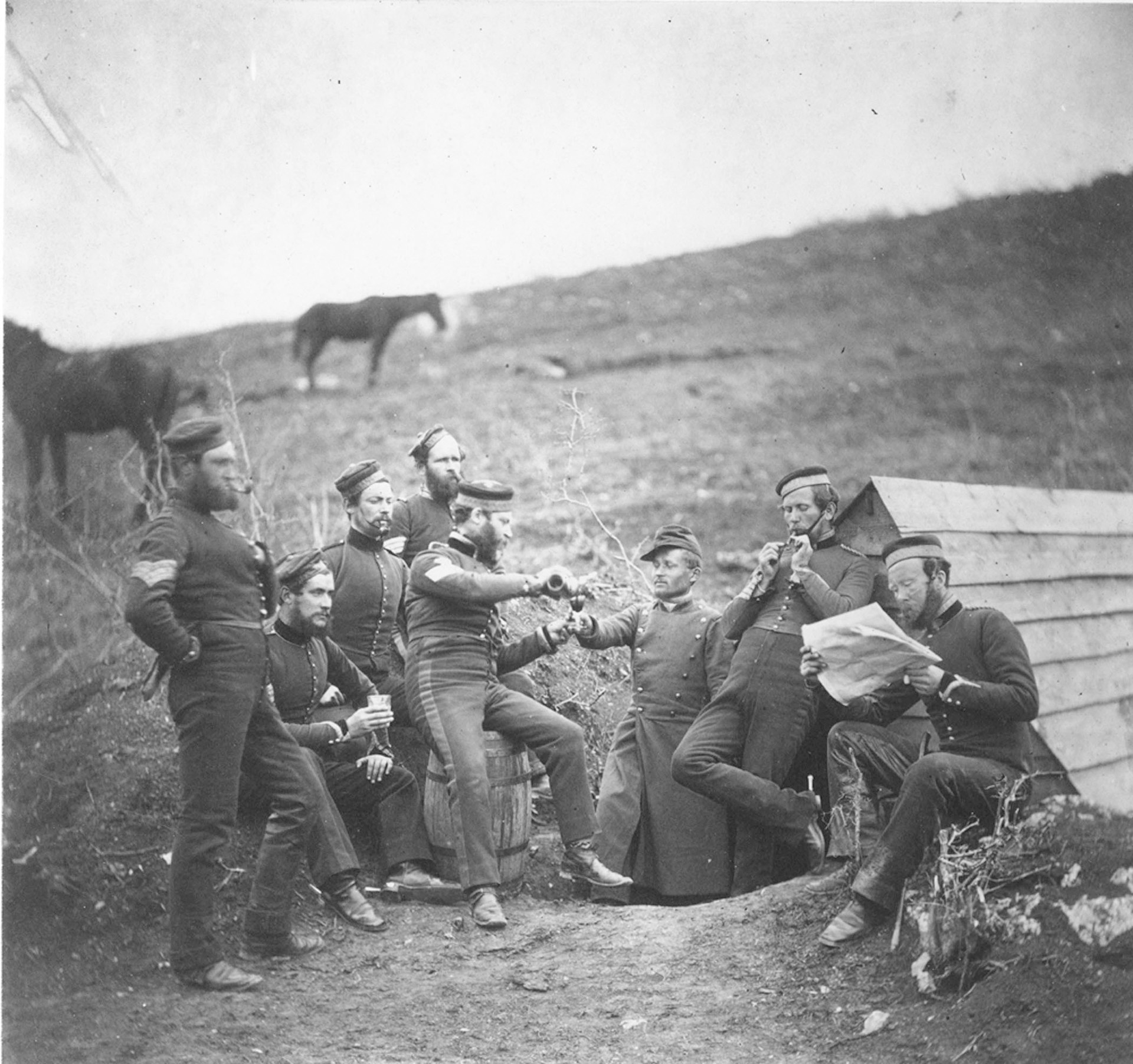

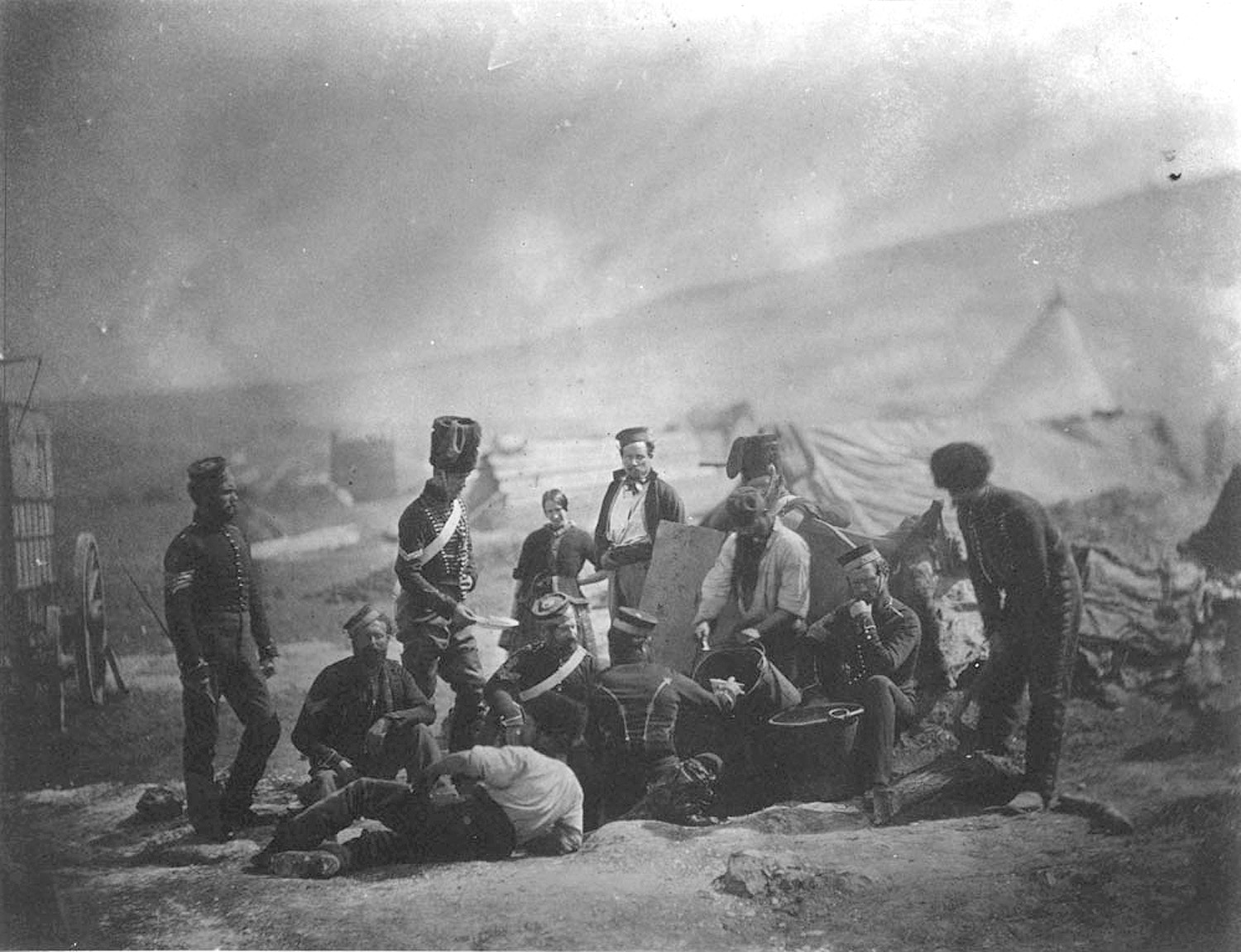

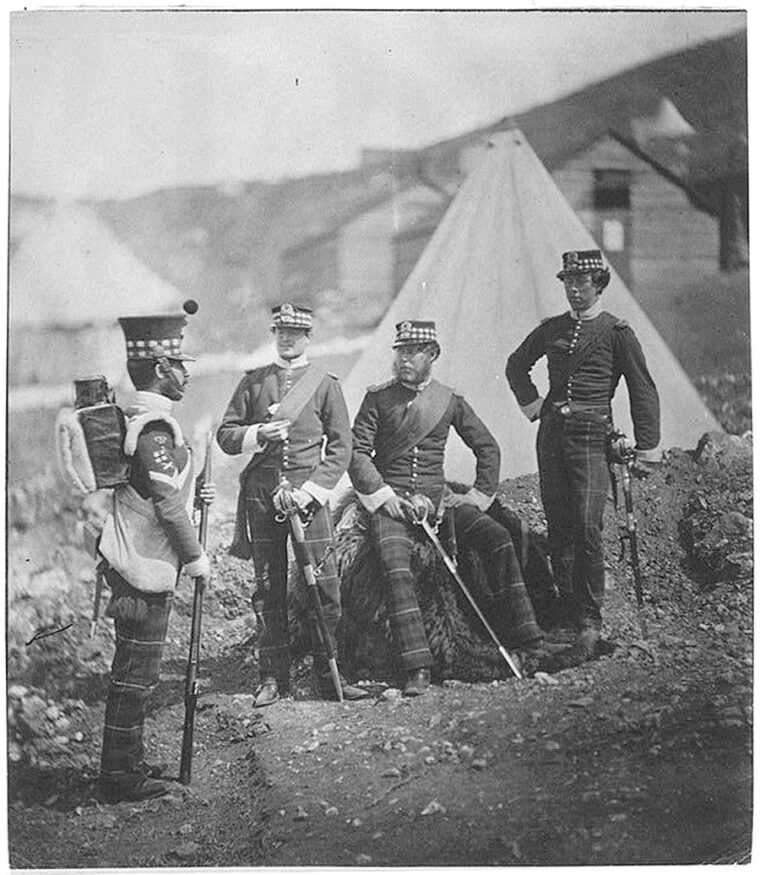

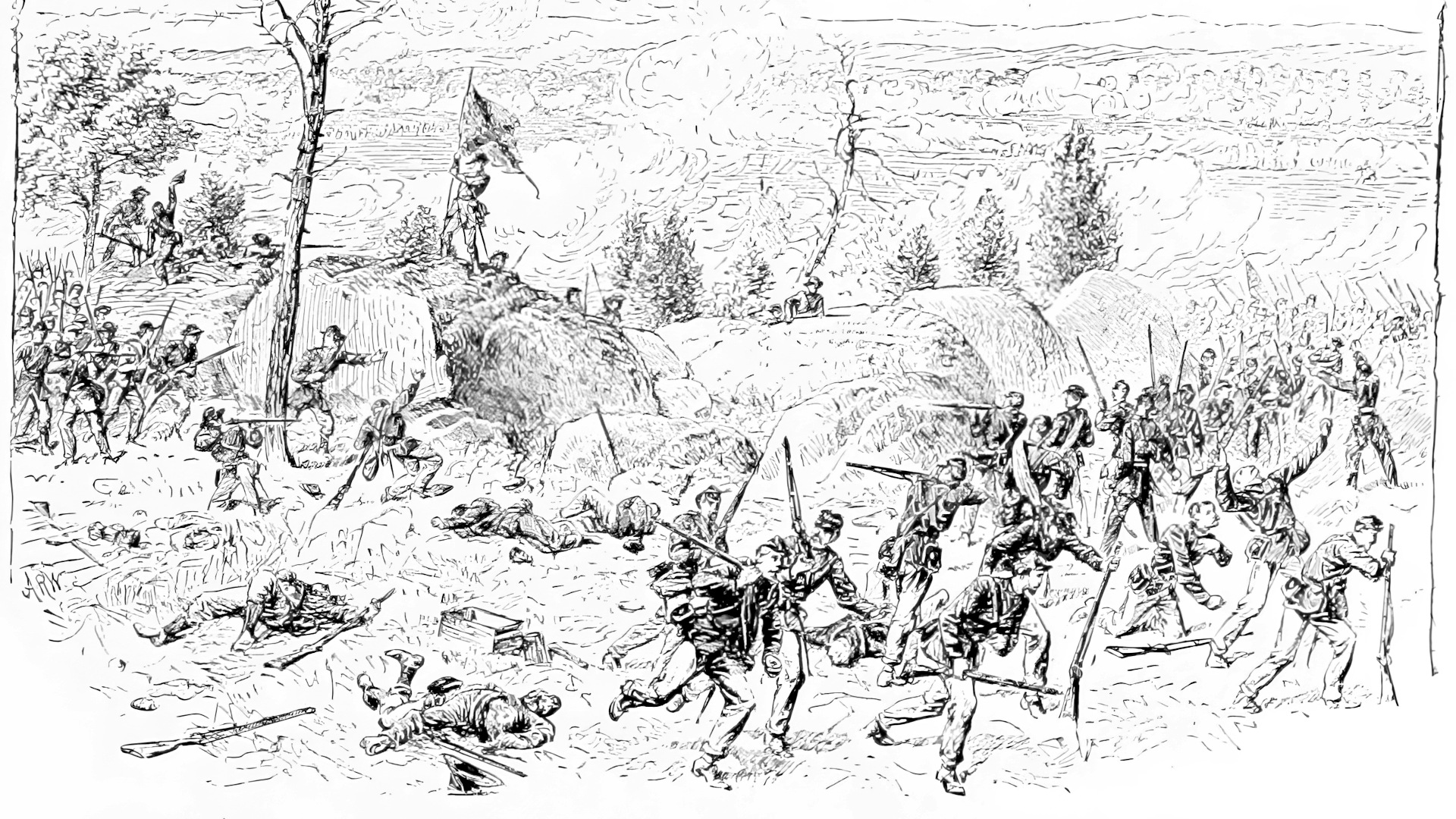

Fenton’s Photographs: No Violence or Dead Bodies

Agnew’s had specifically requested that Fenton refrain from photographing dead bodies or violent scenes. But even if he had wanted to capture a charge or battle scene, the primitive technology of photography at the time meant that any movement would have blurred the image. Therefore, all his scenes showing people had to be posed with everyone standing as still as possible. His early plates took from 10 to 20 seconds to expose, but he managed to whittle this down to a few seconds by the summer of 1855. While developing his plates, his van—mistaken as an ammunition wagon—was frequently the target of Russian shells.

Unfortunately, Fenton came down with cholera and was forced to quit the Crimea before the war’s finale. Sebastopol fell on September 8, 1855, by which time the photographer was en route home. He reached England on the 19th with some 350 exposed glass plates. He had already sent a group of prints on ahead before he left and these went on exhibition at the Old Watercolour Gallery in Pall Mall, London, in September 1855. It was one of the “must see” events of the London summer season and was notable for the numerous distinguished guests who honored the show by their presence. Naturally, these included a number of significant officers who had left the front before the final victory, such as the now infamous Lord Cardigan, General Burgoyne, and French General Bosquet. Fenton was invited to show his photographs to the French emperor, Napoleon III, and in 1856 Agnew’s published a compilation of 60 of his photographs entitled Incidents of Camp Life “taken under the patronage of Her Majesty the Queen.”

Images Strikingly Different From His Competitors

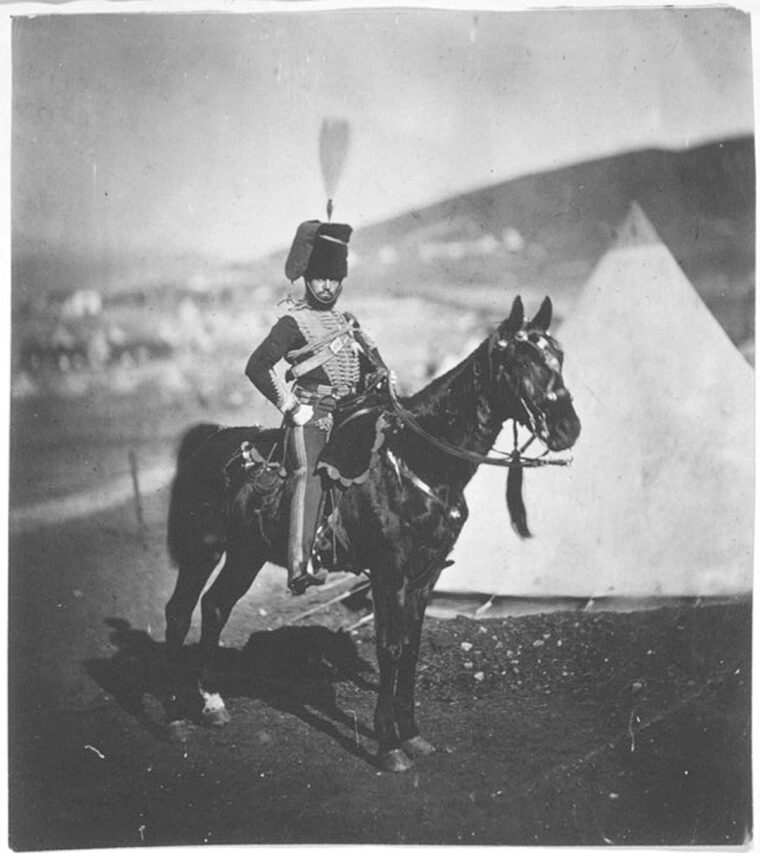

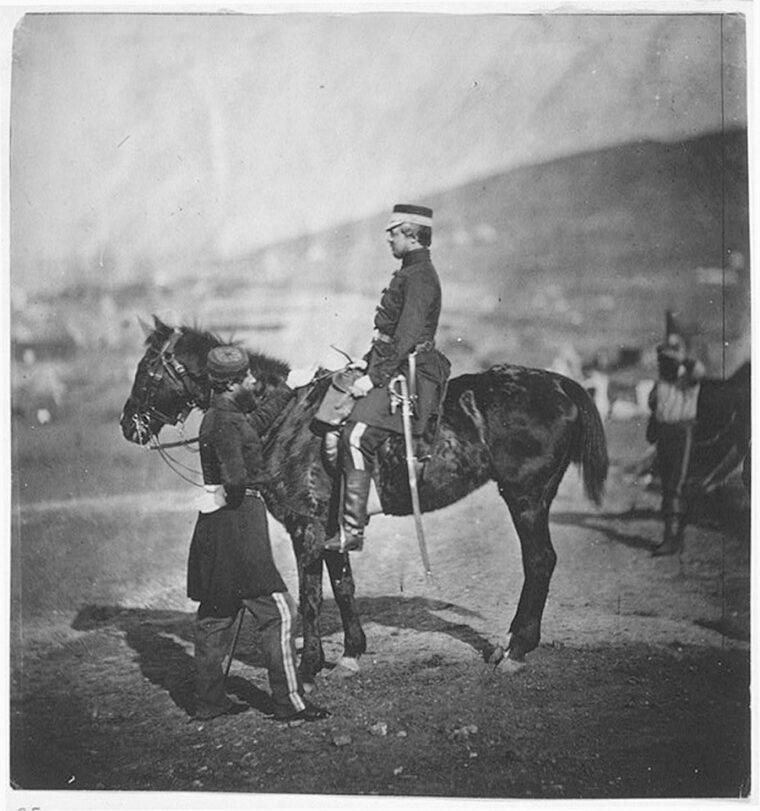

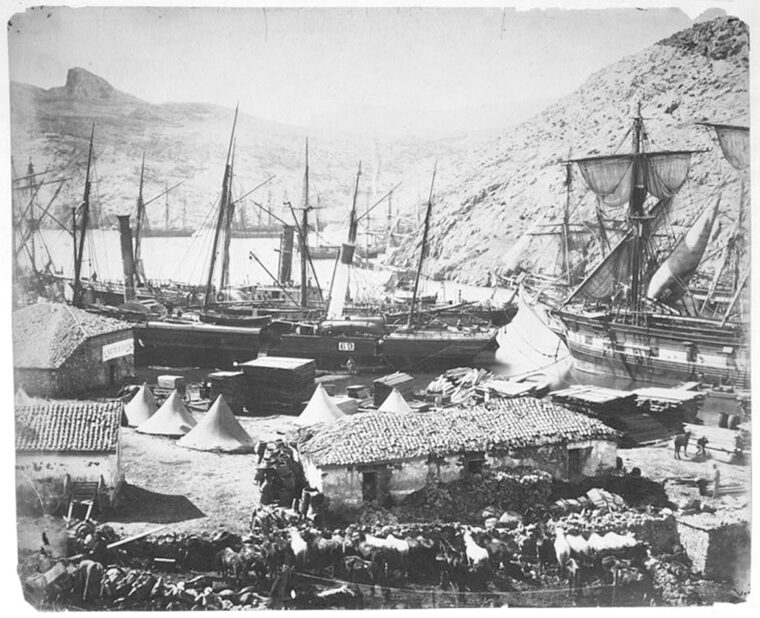

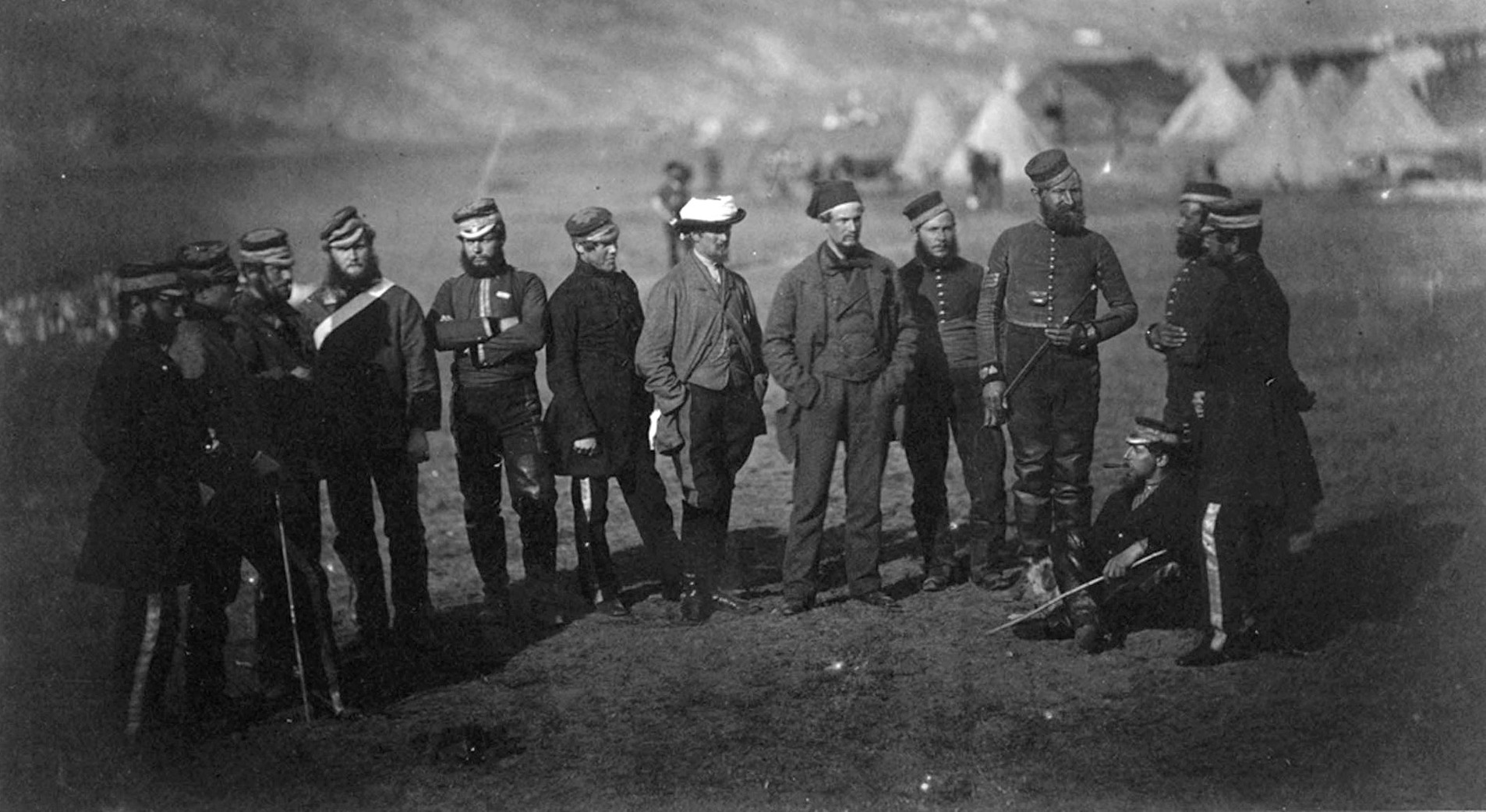

Within a few months, Fenton’s competitors were displaying the products of their own photographic endeavors, but the difference between their images and Fenton’s was striking. Although he did include views of the port of Balaklava and its surroundings, along with some panoramas, Fenton focused primarily on photographing groups of officers and commanders, single portraits, and gatherings of soldiers. The fact that he left the front before the fall of Sebastopol meant he had no photos of the city itself. In contrast, James Robertson and G. Shaw Lefevre had stayed on and were able to reap the benefits. Both took their cameras into the captured place and photographed the scenes of various actions, notably the interiors of the Redan attacked by the British and the Malakoff seized by the French.

Following the war, several committees of inquiry were called to examine the conduct of the Army and its many failures. Numerous members of the general staff were criticized for not concerning themselves with their soldiers’ welfare. Others were chastised for quitting the front before the conclusion of the campaign. While the common soldiers suffered tremendous hardships during the fighting, many of the officers lived in relative luxury. To a great extent, Fenton mirrored this in his photographs. We see officers enjoying the relative comforts of life on campaign. In one notable scene, Lt. Col. Hallewell reclines on the ground as his servant tops up his drink.

Providing a Window Into Life at the Front

Although Robertson and others showed more of the action of the war in their photographs and offer greater historical detail, Fenton’s pictures complement them. His images provide a window into life at the front. We see many characters—Turks, Croats, Montenegrins, and French zouaves—wearing a variety of uniforms. The role of women is portrayed in several plates, including images of French cantinières. Fenton gives us a strong feeling for the open, rugged landscape of the region and the scenes inside Balaklava.

In short, the photographer has given us valuable images of real people caught up in a war rather than imaginary engravings or woodcuts. For almost the first time one can glimpse what it was like to fight in a mid-19th-century war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments