By Dante Brizill

In a message to the Red Ball Express in October of 1944, Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote, “To it falls the tremendous task of getting vital supplies from ports and depots to combat troops, when and where such supplies are needed, material which without armies might fail. To you drivers and mechanics and your officers, who keep the Red Ball vehicles constantly moving, I wish to express my deep appreciation. You are doing an excellent job.”

This was high praise coming from Eisenhower, who knew how important logistics was to the success of his armies in Europe and to the eventual defeat of Nazi Germany. He had seen first-hand over the previous two months how the Red Ball Express had prevented a logistical nightmare in the Allies’ thrust across France.

Judging from these remarks, Ike recognized that no matter how well-trained or numerically superior his forces were, they would be helpless unless they could be adequately supplied with food, fuel, and ammunition.

Conceived in an emergency, the Red Ball Express was an express trucking-supply service that allowed Eisenhower’s armies to keep their foot on the gas at a crucial point during World War II. It is no overstatement that these unsung heroes helped to win the war.

As the theater commander, Eisenhower had some unique, first-hand experiences with army logistics and movement in his years rising up the ranks. His first occurred in 1919, when the young officer was part of a logistical effort to cross the United States in a military convoy.

That year, the U.S. Army Motor Transport Corps embarked on an ambitious project that had two main objectives: to encourage the construction of highways and to demonstrate to the American public the efficiency (or lack thereof) of military vehicles and their performance. It took almost two full months for the convoy to reach San Francisco from Washington D.C.

Along the way, as an observer, Ike noticed numerous breakdowns in discipline, training, and usage of the vehicles. That experience, and the myriad problems he observed, stayed with him even into his presidency over three decades later, when he conceived the idea of an interstate highway system.

The second logistical experience that shaped Eisenhower’s thinking was his participation in the 1941 Louisiana Maneuvers prior to America’s entry into World War II. (Ike was Chief of Staff to General Walker Krueger during the maneuvers.) These exercises were designed to weed out ineffective leadership, evaluate training, and rate commanders and logistics in the Army.

In his wartime memoirs, Crusade in Europe, Eisenhower noted “the efficiency of American trucks and the movement of troops and supply, demonstrated so magnificently three years later in the race across France.”

After the success of the Normandy landings, the Allies had a rough two months battling the Germans in the French hedgerows and bocage country. After being caught by surprise on D-Day, June 6, 1944, the Germans put up strong resistance for the rest of June and most of July in a deadly game of attrition that threatened to parallel the bloody stalemate of the Western Front in World War I.

By late July, with the assistance of massive carpet bombing by Allied airpower, the American and British armies were finally able to break out and pursue the Germans eastward across France. By the beginning of August, Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley turned George Patton’s Third Army loose on the Germans—thus allowing Patton to use his armor, artillery, and airpower in open warfare to devastating effect, employing the same tactics that the Germans had used to conquer most of Western Europe in 1940.

But Patton soon faced a problem: His Third Army was outrunning its supply lines. Enter the Red Ball Express.

The logistical challenge that Patton faced in late August 1944 was due to the Transportation Program implemented prior to D-Day. The crux of this plan was to destroy and disable the French rail, road, and bridge network in northern France in the weeks prior to the D-Day landings.

Without question, the debacles at Dunkirk and Dieppe, as well as the intense German resistance to the landings at Salerno, Italy, still had to be fresh in the minds of the Allied leadership. No repeat of those would be allowed at Normandy.

As Supreme Allied Commander, Eisenhower demanded control—on threat of resignation—over Allied airpower in Europe before the landings. It was essential, he argued, that the Germans—who were masters of the counterattack—not be allowed to rush reinforcements to the Normandy beachhead and interfere with the landings and buildup of the bridgehead.

By May 1944, so much damage had been done by Allied tactical airpower to the lines of communication, particularly the railroads, that movement was almost at a standstill in France. The plan had worked; the Germans could never move enough of their troops to Normandy to seriously threaten to push the Allied Armies back into the English Channel.

But by late August, with the German Army in full retreat eastward across France and the Allies hot on their heels, logistics had become a serious problem for the Allies. The Germans were still holding the major ports at Calais, Le Havre, Brest, and Dunkirk with orders from Hitler to fight to the last man. Cherbourg was in Allied hands, but heavily damaged and in need of time-consuming repair.

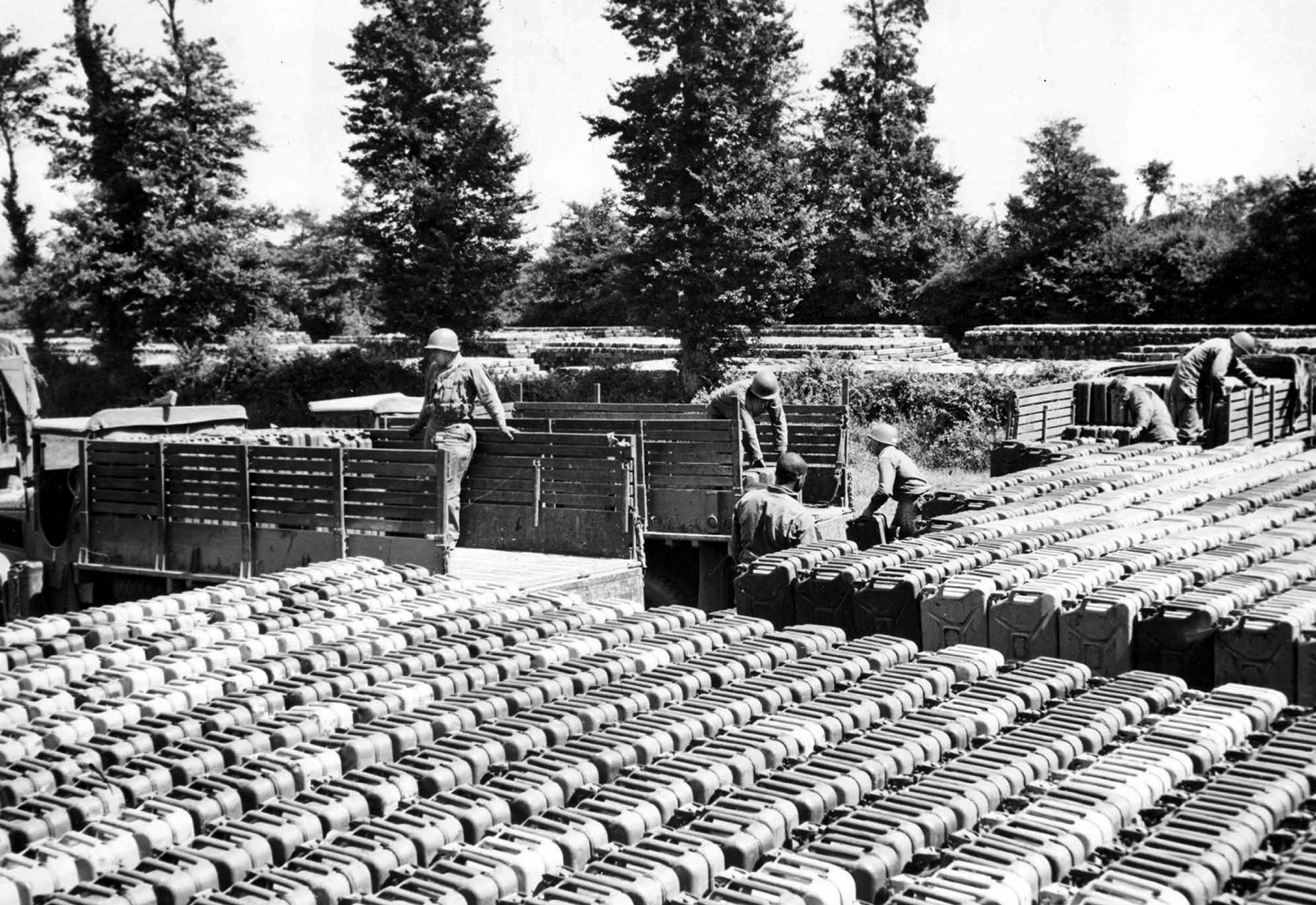

There was a critical shortage of supplies, particularly gasoline. First and Third Armies both consumed as much as 400,000 gallons of gasoline a day, and almost all of the supplies were based in Normandy, with just a few supply dumps nearer the forward areas, which were still several hundred miles away.

It was decided that an emergency trucking system was needed to keep the advancing armies supplied with the essentials. The planners of Operation Overlord did not foresee the front lines moving so fast and so far and had initially planned for a buildup using captured ports and pipelines in the Normandy area. By August, this was no longer a workable plan.

The Red Ball Express was created under these dire circumstances. The term “Red Ball” had origins that harkened back to the 19th century to indicate express rail cargo. Allied commanders put their heads together and in 36 hours created this quick delivery system on August 25, 1944.

This massive new operation would be supervised by Lt. Col. Loren Ayers of COMZ (Communications Zone). Known as “Little Patton,” his job was to gather vehicles and drivers. At first there were not enough trucks, but Ayers scoured units for vehicles and formed provisional truck units for the Red Ball. Then came the matter of drivers. At Ayres’s request, the Army ordered units to turn over soldiers whose duties were not critical to the war effort so they could be trained as drivers—23,000 of them. The majority of these were young African Americans.

Existing Quartermaster units would operate this transport service. The route would start from supply depots in St. Lô and end in the LaCoupe area outside of Paris. Since the French roads, clogged by civilian and military vehicles, were inadequate to support two-way traffic, a one-way loop was set up, with the northern half reserved for the loaded vehicles heading east. Two parallel highways between the Normandy beachhead and the city of Chartres were set aside exclusively for Red Ball Express use.

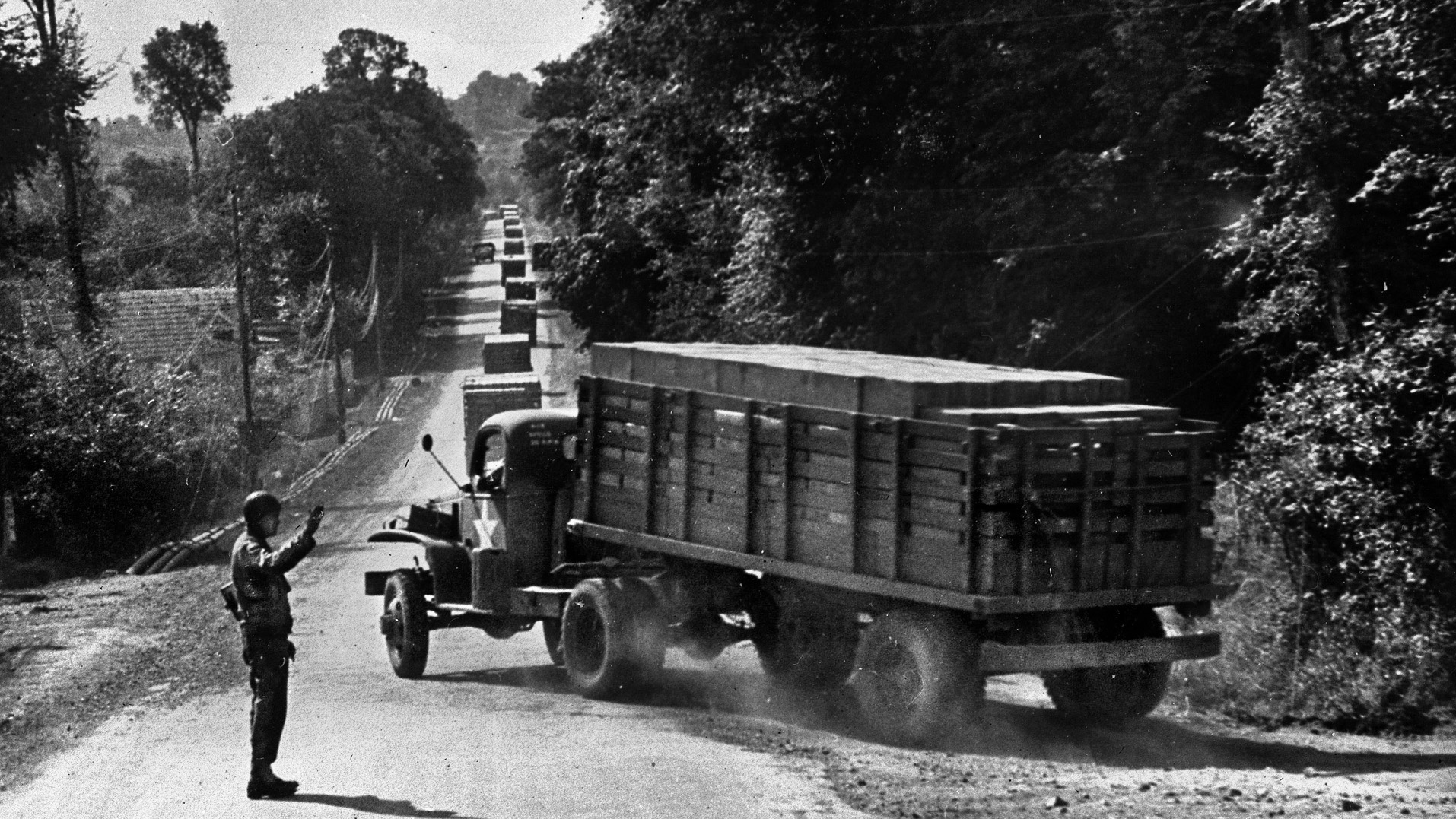

According to the U.S. Army Transportation Corps Museum, “The rules were clear: Trucks were to travel only in convoys. Each convoy was to have no fewer than five trucks each. Each truck was marked with a number showing its position in the convoy, and the trucks were to stay 60 feet apart and travel at 35 m.p.h.” (This speed limit was regularly ignored.)

The Express initially started with 67 truck companies, which ballooned four days later into 132 companies with 23,000 drivers and mechanics. This easy transition to truck transport was due in part to the industrial might of the United States, which produced over two million of the heavy haulers during the war.

Although the Transportation and Quartermaster Corps ran the operation, many branches were needed to make the operation run effectively. Military police played the role of traffic cops, engineers helped to maintain the roads and bridges, and ordnance teams repaired disabled vehicles. Army tactics and doctrine prior to the war emphasized mobility and maneuver, which were put to effective at a time when the German army still relied on horse-drawn transport to ferry some of its equipment.

Three out of four of the men of the Red Ball Express were African American. This was no accident and reflected the deliberate effort by the military during World War II—with a few notable exceptions—to keep African Americans in non-combat and service-related roles.

The second-class citizenship assigned to African Americans in civilian life was reflected in the military, whose leadership did not want to be involved in any “social experiments.” This meant that blacks—serving in mess halls, laundry facilities, janitorial positions, maintenance units, motor pools, and the like—were not to be entrusted with combat.

Assumptions about the mental inability of African Americans to perform effectively in combat predominated among the military brass. Apparently, the honorable service of African Americans in every war since the American Revolution did not amount to much.

The Marines and Army Air Corps refused to admit African Americans until later in the war. The increasingly vocal black press and civil-rights leadership in America persistently pressed President Roosevelt, and the military soon opened more doors to blacks and to provided them opportunities to fight.

Labor leader and civil-rights activist A. Phillip Randolph threatened a march on Washington if defense jobs continued to be inaccessible to blacks, prompting Roosevelt to sign an executive order banning racial discrimination in American war industries.

Segregation was not to be tampered with too much, but the war planted the seeds for its eventual dismantlement within the military after the war. The late Stephen Ambrose, one of the leading historians of World War II, identified the irony of America’s fighting Nazi Germany while maintaining a segregated military when he stated in Citizen Soldiers how “the world’s greatest democracy fought the world’s greatest racist with a segregated army.”

On the home front in 1942, the legendary Pittsburgh Courier initiated the “Double V” campaign in response to a letter it received from a 26-year-old African American cafeteria worker in Kansas, who asked the question, “Should I sacrifice my life to live half American? Will things be better for the next generation to follow?”

The “Double V” campaign represented two battles that had to be fought: racism at home, and fascism abroad. Despite the obstacles, though, by 1943 African Americans were serving in all branches of the military—albeit, in many cases, in supporting roles.

Over 2.5 million blacks registered for the draft, and one million black men and women served in uniform. In the Red Ball Express, they especially shined. The story of the Red Ball Express is one of those underreported gems of World War II that needs to be taken out and polished.

The prejudice that African American troops fought against at home followed them to England, the staging ground for the Allied assault on Nazi-occupied Europe. Interestingly, black soldiers were welcomed by the British population, in many cases with open arms. This brought scorn from many of their white officers and fellow soldiers. British pub owners resisted the Jim Crow customs that some attempted to be imposed on them. Numerous clashes between black and white soldiers occurred around bases in Britain in 1943-44.

Once in France, where the sounds of the guns and bombs could be heard, it was all business for black and white soldiers alike. As a result of the need for drivers for the Red Ball Express, the manpower was there, ready and waiting to be called upon. Many of the men who became drivers had never operated a car before in civilian life and had to be trained quickly to become proficient at their new roles.

The truck most commonly used by the Red Ball Express was the “Jimmy” or “deuce and a half.” This two-and-a-half-ton behemoth with a five-ton cargo capacity was the mainstay cargo transport vehicle of the war and, later, in Korea and Vietnam.

The drivers routinely ignored regulations about maintenance schedules in order to keep the trucks moving and meet deadlines. A common saying was, “Red Ball trucks break, but don’t brake.”

The mechanics often altered the carburetors to make the trucks go past the 50-m.p.h. factory limit. British soldiers joked about quickly scrambling to get off the road when Red Ball trucks approached, and French pedestrians and cyclists also knew to get out of the way of approaching convoys.

Along the journey, the trucks passed the devastation of war: dead and decaying livestock, bombed-out villages, fallen enemy soldiers, burned-out vehicles, and occasionally hungry civilians begging for food. At night, the drivers had to drive slowly using dim lights known as “cat eyes” to avoid being spotted by the enemy.

The men of the Red Ball Express operated with a sense of urgency, knowing how badly their cargoes of ammunition, rations, clothing, spare parts, and medical supplies were needed at the front. According to the Transportation Corps Museum, “An American infantry division required 150 tons of gasoline per day, and an armored division 350 tons per day.”

At its peak, the Red Ball Express operated nearly 6,000 vehicles that carried over 12,300 tons of supplies a day.

Race was generally forgotten by front-line troops in combat. A tank commander whose Sherman was operating on fumes, or a machine gunner who was down to his last belt of ammunition, could not have cared less about the color of the skin of the men who were bringing his precious supplies to him.

As Patton’s army advanced rapidly across France, the drivers often made their own roads so they could unload the supplies his men would need when they got there. Patton’s military police were under orders to make sure that the Red Ball Express drivers were clear to go over roads and not to be stopped.

There could be real danger driving for the Red Ball Express. Karl Koller spoke to the author about his grandfather Rudolph Koller’s service. This Philadelphia native started off driving trucks just after D-Day and later served as a truck dispatcher as part of the 3594th Quartermaster Truck Company.

He recounted a scene that he witnessed: “A column of trucks delivering supplies in Belgium reached a bend in the road. The first two trucks cleared the bend only to be destroyed by a German 88. When the rest of the column stopped, a captain ordered them to continue. The drivers responded that they would only proceed if he led them in his jeep. After pondering their request, the captain decided to find a more secure route.”

African American Cleveland native Lavada Hall served as a first sergeant in the 3715 Quartermaster Truck Company. His grandson Benjamin Hall recounted to the author a story his grandfather told of how “on more than one occasion commanding officers had sent them into areas that were suspected to have enemy soldiers in them, to sort of check and see, because the lives of Black soldiers were not considered as important.”

Mines could be a problem, as well. Sergeant Hall witnessed their devastating effects as recounted by his grandson: “His unit was taking a break to use the bathroom and have lunch. They were pulled over on the side of the road. He went and got his K-ration and returned to his Jimmie. While he was sitting on the bumper eating, one of his soldiers was walking past him. The soldier stepped on a land mine and blew up within feet of where he was sitting.”

Due to the danger from mines, trucks were required to steer to the middle of the highway in areas that had not yet been cleared by mines by the engineers. Drivers often packed sandbags on the trucks’ floors to absorb blasts.

As the armies and the Red Ball Express advanced closer to Germany, the truckers sometimes had to deal with the threat from the air from the Luftwaffe. Even though by this point in the war the German air force was a shadow of what it had been, the Luftwaffe could still be a deadly menace to the Red Ball Express. The planes would appear suddenly and strafe the convoys, forcing the men to quickly exit their trucks and leap into ditches alongside the roads and into the fields.

By the fall of 1944, the Germans had been defeated in France and were pushed out of the Low Countries that they had conquered in 1940. By now, the Allies had seized and repaired the channel ports they needed to bring in supplies to the continent, and the French rail system had been repaired. The opening of the strategic port of Antwerp also greatly increased the flow of Allied supplies in Europe.

Vast convoys of trucks were no longer needed as they once were, and the Red Ball Express no longer had to make the long journey from the Normandy beaches. The Express became a victim of its own success and was officially ended in November 1944. But it would soon face another crucial test that it would pass with flying colors.

On December 16, 1944, Hitler launched one last, desperate operation to win the war in the West—or at least give the Americans and British such a bloody nose that they would agree to a separate armistice.

His armies delivered a surprise attack against American forces in the thinly held Ardennes Forest in Belgium, catching the Allies off guard. In the first few days of the battle, the German forces were able to push themselves deeply into the American lines, creating a “bulge” on the situation maps. Henceforth, the name of the battle would forever be known as the “Battle of the Bulge.”

Because the Red Ball Express had delivered huge quantities of supplies to forward supply dumps in the months before the battle, these were now available to the American soldiers under attack. Another contribution to the victory by the Red Ball Express was the evacuation of thousands of gallons of fuel away from the forward areas. This evacuation successfully kept the fuel out of the hands of the attacking Germans, whose thirsty, gas-guzzling tanks could have used it to exploit their initial breakthroughs.

Early on in the battle, Eisenhower decided to deploy the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions around Bastogne, Belgium, and, once again, the Red Ball Express came to the rescue by transporting thousands of troops into the battle, including the above-mentioned paratroops.

The speed with which these men were moved into the fighting proved to be decisive. The quick action, availability, and speed of the Red Ball Express was a powerful tool that helped to turn the tide of battle.

After the Bulge, the services of the Red Ball Express were no longer required. The U.S. Army Transportation Corps’ Pictorial Handbook of Military Transportation, published in August 1945, contains scores of photos but none of black soldiers; the contribution of blacks is not even mentioned. Given the attitudes of segregation during that era, this is sad but not surprising.

The Red Ball Express might had faded into obscurity had it not been for Hollywood. The movie capital of the world took a stab at telling the Red Ball Express story in 1952. The movie Red Ball Express, starring Jeff Chandler, features an early on-screen appearance by the now-legendary actor Sidney Poitier. The Defense Department, which provided Maj. Gen. Frank S. Ross, Chief of Transportation in the European Theater, as technical advisor to the production, advised the studio that the film should emphasize positive race relations. But the film’s director, Budd Boetticher, claimed that “the Army wouldn’t let us tell the truth about the black troops, because the government figured they were expendable.”

a change of drivers at a makeshift service station near St. Denis, France, September 7, 1944.

From 1973-1974, a short-lived TV series entitled Roll Out, which was based on the Red Ball Express and starred black actors Garrett Morris, Stu Gilliam, and Hilly Hicks, aired on CBS. The series highlighted the daily grind and adventures of the fictitious 5050th Quartermaster Truck Company of the U.S. Third Army. Intending to capitalize on the success of M*A*S*H, the series was designed to be a commentary on race relations during World War II, but only 12 episodes were broadcast.

Nothing was more essential in the summer and fall of 1944 than the pursuit and destruction of Nazi Germany’s military machine. How ironic that a group of men—who could not be served a hamburger or a cup of coffee in some of their hometowns—supplied our armies in Europe with the essentials in the pursuit of victory.

What the Red Ball Express achieved was nothing short of a landmark in the history of military logistics. Initially scheduled to have lasted only two weeks, the service they provided was so crucial to Allied success that it went on for 82 days and delivered over 400,000 tons of gas, oil, lubricants, ammunition, food, medical supplies, and other necessities to supply points near the front lines.

These achievements, of course, came at significant human cost. Scores of black drivers and assistant drivers were killed or injured by enemy fire, land mines, aerial attack, and accidents.

As Eisenhower wrote to the Red Ball Express in October 1944, “The struggle is not yet won. So the Red Ball Line must continue the battle it is waging so well, with the knowledge that each truckload which goes through to the combat forces cannot help but bring victory closer.”

The men of the Red Ball Express helped to win the war, and they remembered their service with pride. These unsung heroes of World War II deserve the gratitude of our nation.

Adapted from the author’s book, Red Ball Express: Greatness Under Fire, published through Amazon KDP in 2020.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments