By Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

It was early spring, ad 235, on the Rhine frontier. In the imperial tent of a Roman encampment, 26-year-old Emperor Severus Alexander wept at his mother’s side. Around them were gathered friends and followers. Fear was in everyone’s eyes. Severus’s mother, Julia Mamaea, had been the emperor’s faithful adviser for a 14-year reign that had brought peace and stability to the Roman Empire. Now, she had no more advice that could save her son, or herself, or anyone else in that tent. Outside, soldiers spat insults, calling the emperor a “timid little lad tied to his mother’s apron strings.” A tribune with a number of centurions burst into the tent. Cold blades flashed in their hands. Screams resounded and blood splashed on the ground. It was all over in an instant.

Severus, his mother, and their followers died because of the discontent born of his indecisive forays against the Persians and, most recently, his shameful offerings of gold to the Germanic Alemanni in exchange for peace. It was an unsettled time for the Roman Empire, with every province seemingly afflicted by barbarous invaders and military despots. Greatest among these barbarians were the Goths, who in a long trek from their Scandinavian and Pomeranian homelands had reached the shores of the Black Sea by the close of the second century. In ad 238, the Danube frontier was hit by the first major Goth raid. The Roman outpost at Histria was sacked. By that time, Severus’s usurper, the towering veteran soldier and bodyguard Maximinus, commanded a Roman army that was exhausted from victorious wars against the Alemanni and the Carpi. Maximinus, who was himself of Goth and Alan blood, was the first of the so-called soldier-emperors. Nevertheless, he was forced to buy the Goths off with a tribute. Maximinus planned to use the time to reorganize his defenses, but the city of Aquilei revolted. Maximinus led his crack field army in a lengthy siege. Reduced to starvation, Maximinus’s own legions murdered him and his son. His desecrated body was thrown to the dogs.

Maximinus was followed by many more usurpers and counter-emperors. The year of his death saw the brutal death of no less than four other emperors and caesars (secondary co-emperors). Fortunately for Rome, the capable general M. Tullius Menophilius managed to restore order along the frontier for three years. The Goth raids resumed when a renewed Persian conflict in ad 242 turned Rome’s attention to the east. Under their war chief Argath, Goth attacks reached a high point in 244. That year, M. Julius Philippus, “Philip the Arab,” became emperor of Rome. Philip bought peace from the Persians and the Moors of North Africa. He then cancelled the tribute paid to the Goths and made war on them and the Carpi. In 248 he took the bombastic titles Carpicus Maximus and Germanicus Maximus. When Philip celebrated Rome’s 1,000th birthday, 1,000 pairs of gladiators, 32 elephants, 10 tigers, 60 lions, 30 leopards, 10 hyenas, 60 wild asses, horses and zebras, six hippos, and one rhino were thrown at each other in an orgy of killing for the amusement of the blood-crazed Roman mob. The lavish festivities convinced Rome’s plebeians—for a time—of the Empire’s undiminished power.

The Fall of Philip the Arab

In reality, provincial revolts in Syria were ongoing, and another major barbarian offensive was unleashed by the legendary king of the Goths, Ostrogotha. In ad 248, Ostrogotha’s great warlords, Argath and Guntheric, led an army of Goths, reinforced by Germanic Taifali and Vandals, Dacian Carpi, and Celtic Bastarne, into Moesia. The heterogeneous nature of the Goth army was reflected in the Goths themselves. Throughout their travels from Scandinavia and on the Black Sea, the Goths had assimilated various other tribal groups and were joined by like-minded barbarians. Their ranks were swelled by Sarmatian tribesmen, Germanic groups, Balkan peoples, Celts, and even Roman deserters. The Goths were more a barbarian coalition led by various warlords than a national entity.

The barbarian army rumbled across the land, a chaotic mass of marching footmen, horsemen, camp followers, livestock, and carts, joined en route by throngs of reinforcements. Hairy, bearded barbarians marched barefoot and bare chested; others were clad in ragged furs or tunics, bows slung over their shoulders, knives in their belts, and clubs hanging at their sides. Most warriors had at least some clothing and weapons looted from the Romans. Wild Alan horsemen draped the skins of fallen enemies over their horses. Sarmatian heavy horsemen in scale mail or “dragon” armor of cloven horse hoofs carried heavy, two-handed lances and deadly composite bows of horn, antler, bone, and sinew. Even their horses were armored. The Carpi footmen boasted the feared two-handed battle scythe that could cut through virtually any armor, and they slung spears over their shoulders, along with oval shields painted with floral motifs. Other barbarians carried wooden rectangular shields and axes.

The barbarian cavalry was usually the best equipped. Among them were the nobles, their bodyguards, and famed warriors. They boasted immaculate ring mail, helmets, axes, spears, and pattern-welded swords forged by master German smiths. They wore fine furs, brightly colored cloaks and tunics; and their weapons, armor, and jewelry gleamed with abstract animal designs of gold and garnets. Dragon and animal trumpets, flags, and standards bobbed over the multitude, who moved slowly but inexorably toward the western border of the Roman Empire.

The thinly spread Roman garrison troops of Moesia could do little but look on as motley Goth bands ravaged the hamlets of the bountiful countryside. Panicked locals abandoned their homes and sought refuge in ancient fortified hilltop shelters. Argath and Guntheric marched to the gates of the city of Marcianople, extorting a hefty tribute. The very size of the booty brought home by the Goths ignited the envy of another Germanic tribe, the Gepidae. Fastida, king of the Gepidae, consequently led his army against the Goths of the elderly Ostrogotha. Although loath to fight his people’s kinsmen, Ostrogotha would not give up his lands without a fight. Savage battle ensued. At last the Gepidae were beaten, establishing the Goths as the dominant barbarian power in the Danube region.

Overstrained by the barbarian raids of ad 248, the Roman legions in the Danube rose up against Philip, who appointed Gaius Messius Decius, prefect of Rome, to bring the region back into order. The 48-year-old Decius was a native of Pannonia and a former governor of Moesia. The local legions killed their rebel leader before Decius’s arrival at their outposts. Assuming command, Decius proceeded to restore order along the frontier. Impressed by Decius’s leadership, his soldiers offered to make him their emperor—or else kill him. Decius reluctantly chose the purple and led his Danube veterans to victory against Philip’s more numerous but less experienced Imperials at Verona in June 249. Philip died on the field of battle, and back in Rome the Praetorians murdered his son and heir. The Senate showed its approval by naming Decius Trajanus after the great second-century martial emperor. Decius soon got his chance to show if he was worthy of the lofty title.

King Cniva Pushes into the Empire

The few soldiers left on the frontier nervously patrolled the forests or kept watch on the ramparts of their outposts. In ever greater numbers, the Goths were again prowling the border like hungry wolves. The legionaries and auxiliaries had more than themselves to worry about. Various settlements had grown up around the legionary fortresses, containing not only shops, taverns, and brothels but also the homes of the legionaries’ wives (many of whom were former slaves) and their children. In ad 249, the fears of the Roman soldiers turned into reality. Ostrogotha’s successor, King Cniva, broke into Roman Dacia with bands of Goths and Carpi. While the Carpi ravaged the villages and wheat fields of their Roman-occupied Dacian homeland, Cniva led his Goth horde across the Danube. Cniva’s army pillaged through the Moesian countryside. Smoke billowed into the sky from villages put to the torch. Rather than risk their lives and those of their families, many Roman soldiers deserted to Cniva, swelling his ranks to 70,000 warriors. Meanwhile, a second group of Goths struck through the Dobrudja marshes, breaking into Thrace to besiege the great city of Philippopolis.

Cniva marched his army to the very gates of Novae but decided to break the siege when he heard that the governor of Moesia, C. Trebonianus Gallus, at the head of his troops, was approaching from the east. Cniva figured that the capture of Novae was not worth weakening his army in battle against Gallus’s forces. Instead, he continued west along the Danube. Ahead of him, masses of locals fled toward Nicopolis, the so-called city of victory. Notably, Gallus made no effort to pursue the Goths. He retained his troops in the defense of Novae and Oescus. Even the approach of the emperor’s youthful son and caesar, Herennius Etruscus, could not induce Gallus to stir. Herennius was bringing with him the Danube legions, which had remained in Italy ever since their battle against Philip’s forces.

At the same time, Decius began the year 250 with yet another brutal persecution of the Christians, whom he blamed for the decline of the Roman virtues. He forced the Christians to pay tribute to Rome’s pagan gods on pain of death. Martyrdoms and upheaval followed Decius’s edicts. The Christians were given a much-needed respite when the worsening situation on the frontier demanded Decius’s personal presence. Decius joined his son before the Roman army closed in on Cniva at Nicopolis. This time Cniva did not run, and battle erupted. Decius inflicted heavy casualties on the Goths, but the outcome of the battle was indecisive and the Romans also suffered heavy casualties. Mass graves were dug for the rank and file, single graves for centurions, officers, and soldiers who had distinguished themselves in battle. Since the Goths were forced to retreat at Nicopolis, their dead remained behind unburied. Bodies of the slain Goths were looted by Roman soldiers and camp followers, and their carcasses left as food for dogs, wolves, crows, ravens, and eagles.

To the south of the battlefield, Cniva audaciously led his barbarians farther into the Empire. His goal was to unite with the second Goth army at Philippopolis. Decius, for his part, remained strong enough to press after the Goths. First the Goths, then the legions, trekked across Shinka Pass on the 4,000-foot-high Balkan plateau. The rough, sloped terrain wore down man and beast. Near Borroea, along the southern foot of the Balkans, the Roman soldiers set up leather tents as Decius stopped to rest his weary army. He guessed that the Goths were far ahead—he guessed wrong. Cniva and his Goths had doubled back to await the Romans. The well-rested Goths lurked in the hills above, watching the Romans for the right time to attack. Suddenly a wild roar and the drone of the bull battle-horn erupted from the hills. Streams of Goths poured down on the Roman encampment. Sentries cried out, trumpets blared, and exhausted soldiers snatched up helmets and spears, but it was too late. Having had no time to dig entrenchments or throw up a rampart, the legions were nearly overwhelmed by the barbarian tide. Decius barely managed to escape into the mountains and reach the safety of Novae with the remnants of his army.

With Decius suitably humbled, Cniva was free to join the second Goth army in the siege of Philippopolis. The city held out for a long time, but there appeared no sign of succor. The desperate Thracian garrison made an offer to the city governor, Titus Julius Priscus. They would proclaim him emperor if he could negotiate a peaceful surrender to the Goths. Priscus, who was the brother of the late Emperor Philip and had a reputation for brutality, was only too ready to turn against his brother’s usurper. It was too late for bargaining, however. Cniva’s barbarians overwhelmed the weakened garrison in a final, violent assault. Once the Goths breached the walls, chaos ensued. Some 100,000 citizens were said to have been massacred in an orgy of raping, looting, and killing. Cniva captured a number of nobles of senatorial rank, including Priscus. With the loot of Philippopolis now in Goth hands, Cniva decided to proclaim Priscus emperor after all. Further dissension among the Romans could only aid Cniva. Priscus did not survive his treachery for long. Soon afterward, he disappeared from the scene, probably killed by Cniva after another change of mind.

Attack is the Only Retreat

While Cniva wintered his army at Philippopolis, Decius joined Gallus’s forces at Oescus. Too weak to march south and confront Cniva, Decius wisely used the time to reorganize his army, recruit new troops, and restore discipline. Decius did manage to intercept and defeat a number of Carpi venturing too far south. The Danube fortifications were also strengthened, and Gallus was sent to guard the crossing at the mouth of the Danube. Decius stood guard farther west with the main army, while proven officers were sent to picket the mountain passes and make sure no new reinforcements could reach Cniva.

Cniva began his trek home with the first green grass of 251. Unlike Decius, Cniva found his army in inferior shape from the previous year. The casualties suffered during the siege of Philippolis had not been replaced, and the countryside had proven incapable of sustaining the Goth army during the winter. Cniva tried to bargain with Decius, offering to surrender the spoils of Philippopolis and the captives in return for safe passage back north across the Danube. Decius, however, would only accept unconditional surrender. To the Goths this meant certain slavery. They had little choice but to fight their way out. Cniva marched his army back north, slowed by ranks of hapless captives and heaps of loot. His thoughts focused on the well-supplied Roman troops that awaited them north of the Balkans.

The Roman pickets stationed at Shinka Pass warned Decius that the Goths were drawing near. Before he reached the Danube, Cniva was intercepted by Decius near the city of Forum Terebronii, called Abritta by the Goths. By this time, Decius’s army had been reinforced by the bulk of Gallus’s troops. Leaving nothing to chance, Decius also curried the favor of the gods by offering sacrifices. After scouts reported that Cniva’s army had entered the nearby swamplands of the Dobrudja, Decius decided to follow them and finish them off.

“Let No One Mourn”

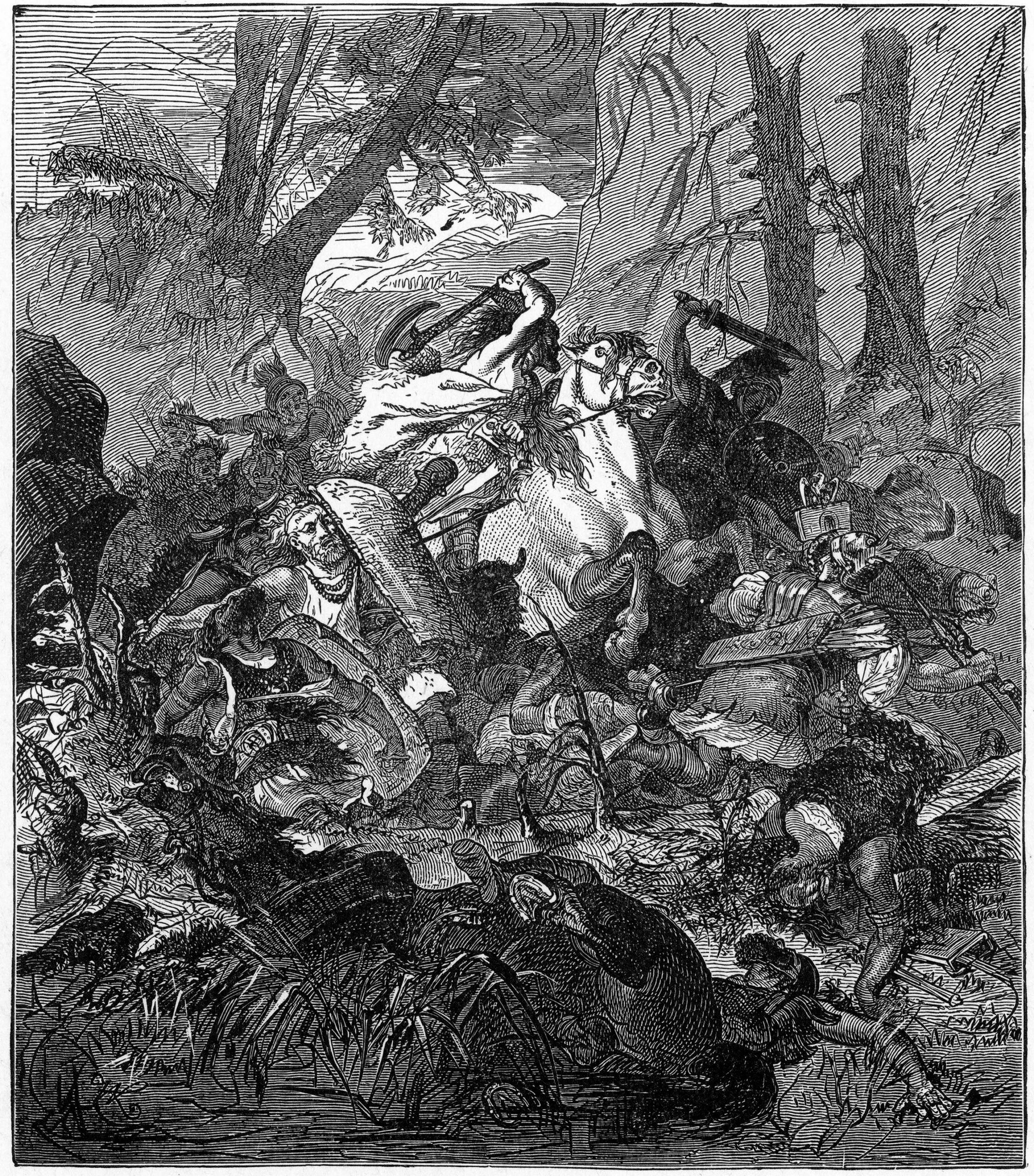

What Decius did not consider was that Cniva might be drawing him into the swamp on purpose. Two centuries earlier, the Roman legions had sustained one of their worst defeats when they were ambushed by the Cherusci in the Teutoburger forest. Like the Cherusci, the Goths were familiar with fighting in the swampy wilderness, terrain that could negate the superior Roman discipline and equipment. Cniva divided his army into two bodies and a smaller reserve force. He planned to surround the Romans.

The Goth divisions watered their horses and bundled up rations as they prepared to cross the swampy ground separating them from Decius’s army. Somehow their approach went unnoticed by the Romans. Goth archers strung their bows, notched their arrows, and drew back the strings. With a sudden swoosh, a cloud of missiles showered the Roman lines, thudding into wooden shields, glancing off iron helmets and mail, and penetrating flesh. One arrow pierced Herennius, who had recently been elevated to co-leadership by his father. His reign would be a short one. The Goths charged into the startled Romans, who frantically sought to form their lines. Barbarians poured over Herennius, plunging spears into his wounded body. The first shock wave nearly broke the disheartened Roman lines. Decius, seeing his soldiers falter at word of his son’s death, cried, “Let no one mourn. The death of one soldier is not a great loss to the republic.” Centurions in red officers’ tunics rallied their men and held their ground. Roman swords and heavy javelins thrust from behind a wall of oval, brightly painted shields.

Despite his brave words, Decius was overcome with grief and anger. He would not rest until all the Goths were killed or he had joined his son in death. Decius led his legions into the Goths and ripped their ranks to pieces. Roman cavalry galloped through the marshy ground, hoofs flailing up clumps of dirt. Keen spears and long swords hacked down the barbarians. Here and there, lone Goths remained fighting against the Roman onslaught until the thunder of cavalry hoofs resounded over the swamp as the second Goth division entered the fray. Once more, hordes of wild barbarians hurled themselves against the Roman lines. Again the Romans repelled the attackers. The swamp was strewn with dead and dying barbarians.

The battle was won. Decius roused his battle-weary troops to pursue the third and smallest Goth division. Centurions bellowed orders as worn-out soldiers formed behind standards borne by the bearskin-draped aquilifers. The legionaries gritted their teeth. Robust and often around six feet in height, most of them hailed from provincial farming communities and were used to a life of hardship. Seventeen-year-old recruits took comfort in the resolute professionalism of veterans, some of whom had served beyond their required 26 years. The cohorts trudged deeper into the swamp, but with each mile there were more pools of water to wade through and deeper mud to sink into, draining strength from the heavily burdened Romans.

Barbarian survivors drifted into Cniva’s camp, exclaiming that their first two divisions had been routed. Decius was coming after them, but he had lost his way and foolishly led his legions into a virtual quagmire. Cniva must have smiled; he would snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. Gathering the survivors of the first engagements, he led his last reserves against Decius. The legionaries cursed as they lifted one exhausted leg after another from the sucking mud. Sweat poured relentlessly into their eyes. Mosquitoes stung their skin, buzzing and crawling through their helmets’ guards. The Romans’ assortment of armor grew heavier and heavier. Suddenly, from all sides, throngs of barbarians ran to within javelin range. Volley after volley of missiles peppered the strung-out Roman ranks. Tired arms lifted shields to protect against the barrage. Most of the arrows and javelins sliced into the water, but many found their mark.

Wounded legionaries collapsed into the mud, gasping for air as they were swallowed by the morass. Overcome with anger, the Romans used their last reserves of energy to come to grips with their foes. They broke rank and charged after the barbarians. The Goths simply retreated into the wilderness, leading their pursuers into ever-deeper pools of water and separate ambushes. When the Roman army was worn down and fragmented by the relentless missile fire, the barbarians closed in. Spears stabbed through mail, fire-hardened clubs bashed in helmets, swords and axes split skulls and chopped off limbs. The waters ran crimson. No one was spared, not even the emperor. Decius’s body was never found. He was the first—but not the last—Roman emperor to be slain by the Goths.

“The Age of Thirty Tyrants”

When news of the disaster spread to the troops to the north, they proclaimed Gallus the new emperor. The purple around his shoulders, however, did nothing to aid Gallus against the Goths. With the main Roman army destroyed, Cniva was now in a position of total power. The way was clear for barbarian reinforcements, eager to capitalize on Cniva’s success, and more deserters flocked to Cniva’s banner as well. Cniva no longer desired to return home. He turned instead to ravage Moesia, Thrace, and Illyria. The Roman troops left to Gallus were no match for the Goths. To rid Roman soil of the barbarian scourge, Gallus not only let the Goths keep their booty and captives but also promised to pay the Goths a sizable annual tribute in gold.

Back in Rome, Gallus’s concessions proved unpopular with the citizens. That they had to pay the barbarians with gold was an outrage. Gold was all the more valuable since Roman coinage, the denarii, had become so devalued that some coins were little better than base metal with silver wash. As it turned out, loss of prestige was the least of Rome’s worries. Usurpers, Persians, and barbarians caused the empire to loose control over vast territories. After the Battle of Abritta, Roman fortunes spiraled down. Gallus’s successor, Publius Licinius Ignatius Gallienus, faced so many pretenders during his reign that it was exaggeratedly called “the Age of Thirty Tyrants” (actually there were only 19). In 260, one of these tyrants, Cassianus Latinius Postumus, set up his own independent Roman Gallic Empire and gained the allegiance of Britain and Spain.

Persia’s King Shapur eagerly exploited Rome’s weakness. Shapur found an excuse for war when his tribute was cancelled owing to the new tribute that Gallus had to pay to the Goths. Shapur assassinated the pro-Roman Armenian King Choreses, replaced him with one loyal to Persia, and rampaged through the Roman province of Syria, the bulwark of the Roman defense in the Near East. The Roman reprisal, led by Gallienus’s father and co-leader, Publius Licinius Valarian, ended in a colossal Roman defeat in ad 260 on the Euphrates River. Valarian was killed and his body stuffed and put on display in a Persian temple.

Gallienus had no chance to avenge his father. Plague swept through the Roman Empire in 262, killing up to 5,000 people a day in Rome, and the Rhine and Danube frontiers were enflamed by warfare. Individually, the barbarian armies were not large, but there were many different people invading at many different points. In 258, the Alemanni drew so dangerously close to Rome that the Praetorians were unleashed to ward off the invaders. The pretender Postumus managed to restore Roman authority in Gaul, but six years after his death in 268, the Franks captured more than half the towns in Gaul. Rome’s bitter enemy, the Marcomanni, also reappeared, conducting numerous forays into Pannonia and forcing Gallienus to cede part of the region to them.

The Beginning of the End of an Empire

Nothing compared with the threat of the Goths. Gallus’s tribute only enticed the Goths’ greed for more. Although little more was heard of Cniva, other warlords led Goth hordes on land and seaborne invasions. Rome still managed to win the occasional victory, but the Empire was unable to prevent the looting of its eastern territories. The Goth attacks threw Greece into such a panic that the walls of Athens, neglected for more than three centuries, were rebuilt. The same year, the Sarmatian Borani, allies of the Goths, forced a Roman vassal, the Kingdom of Bosporus, to surrender its fleet and crews. On flat-bottomed timber barks, with only a shelving roof for cover, the Borani sailed to the city of Pityus on the western slopes of the Caucasus. Pityus’s Roman garrison hurled back the invaders from its stout walls and chased them off. A year later the Borani were back, together with the Goths. This time they seized Pityus, whose valorous garrison was recalled to Rome.

The Goths next appeared below the double walls of the opulent city of Trapezus. The city boasted a garrison reinforced by 10,000 men, most of whom unfortunately spent the nights in drunken festivities. No one noticed the Goths, who stealthily climbed the walls at night, using trees they had felled for the purpose. The shocked population awoke to the terror of barbarians killing, raping, burning, and looting through the streets. The cowardly garrison soldiers managed to flee out an opposite gate. The spoils of Trapezus were immense. Its holy temples were stripped bare, and endless throngs of captives marched to the Goth and Borani fleet. Chained to the oars, they rowed their conquerors back to Bosporus. Their appetite for loot not yet stilled, the Goths returned to loot the cities of Bithynia’s western coast. Only the fall equinox, after which the Black Sea turned treacherous, recalled the sea raiders to their northern homes.

For 10 years the Goths stirred little as they lived off the rich spoils of their plunder until their old Scandinavian neighbors, the Heruli, appeared on the Black Sea. In 267, together with the Heruli, who were expert seamen, the Goths broke through the Dardanelles and sailed into the Aegean and the Mediterranean seas for the first time. Their way south open, Goths and Heruli landed near Thessalonica, ravaged Attica, and looted the hinterland of Asia Minor. Their naval spearheads reached as far as Rhodes and Cyprus. Swarms of barbarians roamed through the luxuriant theaters, temples, and baths of the Empire’s cities, taking what they wished, burning and looting what they could not take. Their greatest prize was the destruction of the famous temple of Diana at Ephesus, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

The Goth triumph at Ephesus proved to be the high-water mark of their third-century invasions. Emperor Marcus Aurelius Valerius Claudius struck back with a spirited naval and land counteroffensive that was so complete that it eliminated any major Goth threat for the next 100 years, earning Claudius the victorious name Gothicus. Claudius and other able soldier-emperors restored the security of the Empire, although Dacia was permanently lost to the Goths. By the time of Diocletian and Constantine the Great, Rome seemed destined for a new Golden Age. But if the Goths were temporarily cowed, other barbarians were not. When the Goths did return, in the latter half of the 4th century, they carried all before them. Finally in 410, Rome, unconquered for 800 years, fell to their spears, heralding the final dissolution of the Roman Empire.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments