By Kevin Seabrooke

As darkness fell along the upper Saigon River in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta region, one of two River Patrol boats of the U.S. Navy’s “Operation Game Warden” River Patrol Force cut its engines and nosed up to the riverbank. Three figures leapt from the boat and disappeared into the thick jungle. The second boat continued ahead, then did the same and three more figures disappeared. The men were part of an Army Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol (LRRP), a six-man ambush team that would search for Viet Cong and provide security for the waterborne two-boat guard post watching for enemy traffic on the river.

It was August 2, 1969, and 21-year-old Petty Officer David Larsen was the gunner’s mate aboard Patrol Boat, River (PBR) 775, one of the two boats that would wait there until dawn. In the beginning of Operation Game Warden, the boats would move quietly along the channels and canals, but in the silent darkness, the engines were too loud even at the lowest rpms. So now the tactic was to wait near a suspected enemy crossing, tied up at the bank, or under some trees, maintaining radio silence. Watching and listening for the whispers and small splashes of the enemy crossing the river, more often waiting for hours with nothing happening.

The River Patrol Force (Task Force 116) was created in December 1965 by the U.S. command in Vietnam to stop the flow of men and materiel flowing from Cambodia into the Mekong Delta. By March 1966, Operation Game Warden was underway, using 31-foot fiberglass river patrol boats with enlisted crews of four to stop and search river traffic.

Based on a commercial design by the Hatteras Yacht Company, the Mark I and Mark II PBRs were built by United Boat Builders of Bellingham, Washington. The fiberglass hulls were impervious to marine boring creatures and didn’t produce wood splinters or metal shrapnel like other boats when hit by enemy fire. It weighed 14,600 lbs. with a draft of 26 inches and was powered by two General Motors 220-horsepower diesel engines, with a top speed of 20 knots. Two jacuzzi water-jet pumps propelled and steered the Mark I, making it highly maneuverable, able to stop quickly and turn around completely. It was equipped with a Raytheon Pathfinder surface search radar and two AN/VRC-46 radios. For armament, it had three .50-caliber machine guns—two in a turret at the bow and one mounted at the stern. They usually carried an M-60 machine gun, a 40mm grenade launcher amidship.

The PBRs usually worked in pairs, with one boat intercepting and boarding sampans, junks and other river craft, while the other stood off watching for ambushes. At night, the PBR crews had more latitude in dealing with river traffic—all of which was assumed to be hostile as there was a dusk to dawn curfew. They crews could radio in for permission to fire on a vessel but, if fired upon, they were free to return fire without direct orders.

Once the patrol commander was sure the enemy was in the water, both boats opened fire with their machine guns and grenade launchers. Artillery or air support could also be called in.

By 1967, working with heavily armed Bell Aviation UH-1B and UH-1M Huey helicopters, these PBR patrols were limiting enemy activity on South Vietnam’s larger rivers. Nicknamed “Seawolves,” the Helicopter Attack (Light) Squadron Three (HAL-3) provided close air support for the Game Warden River Patrol Force as well as armed reconnaissance and fire support for Navy SEALs.

In addition to the PBRs and other U.S. resources flowing into South Vietnam for Operation Game Warden, the River Patrol Force oversaw an increasing number of SEALs. Three 14-man platoons each from the Atlantic Fleet’s SEAL Team 1 and Team 2 were deployed in the delta region.

The main role for the SEALs for Task Force 116 was intelligence gathering—location and capabilities of enemy units and possible attack plans. The highly trained six-man SEAL units avoided combat, if possible, but carried out many ambushes in day or night and ran raids to kill or capture Viet Cong leaders or couriers. Though SEALs could use a wide variety of craft on the rivers, they were often transported by River Patrol Force PBRs or the HAL-3 helicopters, which also provided armed support and stood by to pick them up after their operations.

In July 1968 an officer in tactical command of a SEAL detachment described operations in the vast mangrove swamps of the delta south of Saigon known as the Rung Sat Special Zone. In an end-of-tour report, he wrote that “the foliage is so thick that it is not unlikely for a patrol to be within a Viet Cong base camp and not realize it. Visibility is sometimes only 5 to 10 feet and silent movement is practically impossible. . . . In a firefight with a concealed enemy at a range of 5 to 10 meters the possibility of losing at least the first two members of a friendly patrol is great.”

Up on the Saigon River, sometime after dark on the night of August 2, Petty Officer Larsen and the crews of the two PBRs heard shots and then the explosion of rockets. Larsen and the rest of the crew took their stations, ready to provide cover for the retreating ambush team. Their orders required them to stay on the boats.

Soon after the explosions split the night, a call came over the radio asking the PBR crews for help. The ambush team had engaged four enemy soldiers who turned out to be part of what was later estimated as a force of 35-50 men, who returned fire with rockets, killing or critically wounding five members of the team.

Larsen said later that he grabbed the M-60 machine gun and jumped, almost falling off the boat as his crew tossed him ammunition belts.

Arriving just as the ambush team was about to be overrun, Larsen fired the M-60, killing one enemy soldier, forcing the two others to flee.

Larsen maintained a one-man perimeter defensive position under continuous enemy fire until help arrived.

The citation for the Navy Cross describes Larsen as “the first man to take his post on the perimeter established to provide security for the medical evacuation helicopter. By his extremely courageous one-man assault in the face of direct enemy fire, Petty Officer Larsen was responsible for saving the lives of three fellow servicemen, and for protecting his shipmates as they administered aid to the wounded.”

Eight men earned Bronze Stars that night, though they broke the rules in leaving the boat.

“At the time, it just comes to you that you need to do it to get the job done,” Larsen would later say.

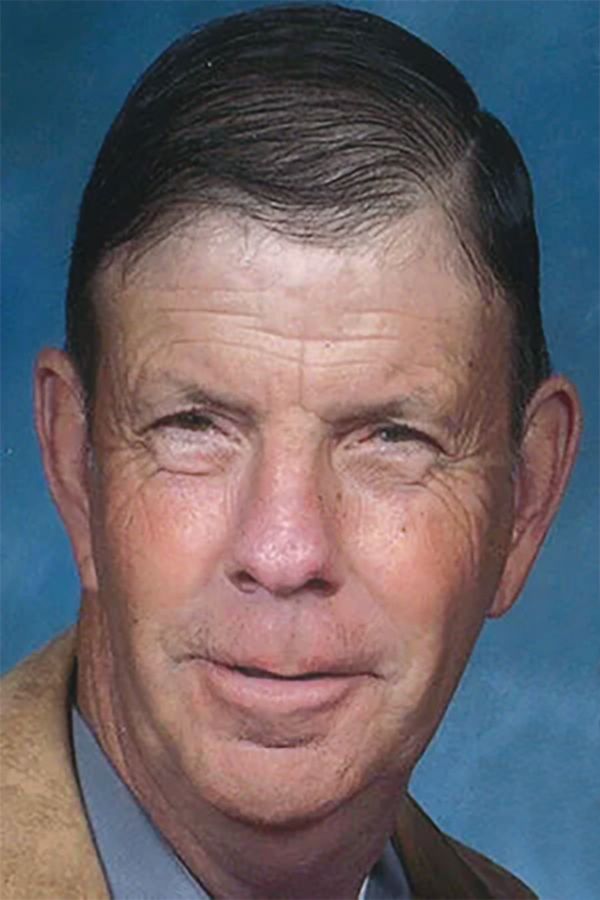

Larsen grew up in Kansas and joined the Navy in 1966 right out of high school. He went to boot camp in San Diego, California. After boot camp, he was at Bremerton, Washington, before serving a tour of duty aboard the USS Ranger in Vietnam. From there he went to Korea when the USS Pueblo was captured.

He returned stateside for survival, evasion, resistance and escape training and language school in San Diego. Training complete, he was sent back to Vietnam where he served a year on a PBR in River Division 593, River Patrol Flotilla FIVE, Task Force 116 (TF-116).

During his tour on the river, Larsen would receive not only the Navy Cross, but also a Bronze Star and two Purple Hearts, as well as several other medals and awards. He completed his fourth year of enlistment stationed about the USS Oriskany in San Diego and would serve one year in the Navy Reserves.

Throughout his life, Larsen would maintain that during his time in Vietnam, he really only had one goal: “stay alive and make it back to Kansas.”

Larsen would return to Parsons, Kansas, where he was born, and live an active life in the community, serving as a volunteer firefighter, a member of the Parsons Planning Commission and Parsons City Commission. He also was a past president of U.S. Gamewardens Association of Vietnam, as well as a member of the U.S. Gamewardens Board of Directors.

The City of Parsons proclaimed November 12, 2001, as “David R. Larsen Appreciation Day” and named a street after him. His experience in Vietnam has been mentioned in several books and his actions on August 2, 1969, have been featured in two television shows, The

Discovery Channel’s “Battle Zone,” in 2007, and an episode of The Smithsonian Channel’s “Weapon Hunter” in 2015.

Larsen died at home in Parsons at the age of 75 on November 2, 2022.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments