By David H. Lippman

To those that met him, Lieutenant General Arthur Percival was uninspiring and gloomy, seeing difficulties rather than opportunities; one who was weak and hesitant when a decision was needed.

He was a thin man with two protruding teeth that made him look like a rabbit. When he wore his Wolseley tropical pith helmet, his men ridiculed him behind his back. He was neither ruthless, nor brilliant, nor hard-driving. He had no experience of top-level leadership when he was given the Malaya command.

He was a meticulous staff officer who could write reports to perfection. There was no question of his battlefield courage: he suffered five wounds in the Great War. He was an excellent athlete, too: winning cross-country runs and excelling in equestrian events.

Such was the man who would lead the Commonwealth ground forces in Malaya to the greatest defeat in the history of the British Empire.

Percival was born on December 26, 1887, in Aspenden, Hertfordshire, attended Rugby School, and clerked for an iron-merchant company in London. When the Great War broke out, Percival joined the Bedfordshire Regiment and gained an immediate commission. Gallant in action, he was awarded a Military Cross, Distinguished Service Order, Croix de Guerre, and the brevet rank of major, along with five wounds.

After surviving the trenches, he was assigned to the 46th Royal Fusiliers, part of the ill-conceived Allied intervention in North Russia. Percival gained a bar to his DSO in those actions. From there, he joined the 1st Essex, gaining both the IRA’s hatred and an Order of the British Empire—both for his efficiency, mostly in gaining information from captured suspects.

A man with his field experience was a logical choice to attend the British Army Staff College at Camberley, where he ran cross-country and learned that the defense of Malaya would be based on the Army holding off Japan until the “Main Fleet” and aircraft arrived at the bases being built on the peninsula and Singapore.

He married Betty McGregor in 1927, and the union resulted in daughter Dorinda and son James. Percival drew more important appointments: studying at the Naval Staff College; instructor at Camberley, where he impressed Field Marshal Sir John Dill; student at the Imperial Defense College; promotion to full colonel in 1935.

Percival was then assigned as General Staff Officer One (GSO1) to the Malaya command, then under Major General William Dobbie. His work was planning the defense of Singapore, doing so with meager funds and fewer troops. His appreciation supported Dobbie’s views that Malaya could be conquered by a Japanese drive from the north, down the west coast roads, and besieging Singapore. Dobbie also pointed out that the many airfields the RAF had constructed in north Malaya could not be defended with the forces presently assigned and firmer steps needed to be taken.

Dill, now commanding at Aldershot, was impressed by this report. When war broke out, Dill was assigned as commander of the British Expeditionary Force’s 1st Corps, and he took Percival to France with him as Brigadier General Staff. Percival was soon promoted to command the 43rd Infantry (Wessex) Division, training in Wiltshire, as a major general.

He didn’t last long there. When the 44th Infantry (Home Counties) Division staggered home from Dunkirk, Percival was put in command, and he put it through anti-invasion duties through March 1941. Then he received the fateful news that he had been promoted to lieutenant general and appointed General Officer Commanding Malaya.

Percival arrived in Malaya to find his command in poor shape. The peninsula was defended by the 11th and 9th Indian Divisions and the 8th Australian Division. In theory, they were the finest elements of the British Empire. In reality, the Indian forces lacked veteran NCOs and skilled officers—the best had been sent to North Africa. The Australians had similar problems. Many of their troops were badly trained and described as “sweepings off the streets of Melbourne and Sydney.”

Almost none of them had any serious jungle training. All the leaders would look at maps, see jungles and swamps, and concentrate on defending the many roads—which would prove critical to the Japanese assault.

The promised aircraft to defend the bases never arrived. The F2A Brewster Buffalos were outclassed by Japanese Zero and Oscar fighters. Malaya’s Supreme Commander, Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, a Great War flying ace, said, “Let England have the Super-Spitfires and Hyper-Hurricanes. We can get along all right with what we have here.”

Brooke-Popham’s attitude to defense reflected that of the British Malayan and Singapore population. Malaya may have been part of the British Empire, but there was no urgency at any level to replicate the intense defensive measures of England, from Air Raid Precautions to hiring labor to build defense lines, to creating sabotage teams to attack invaders after their advance. Despite being General Officer Commanding, Percival made no effort to change this mentality.

Though legendary, the Singapore Fortress had a critical weakness. It wasn’t the popular myth that the guns could not fire northward—they could. Its magazines were filled with armor piercing shells— useless against infantry.

Nonetheless, Percival planned in accordance with his own pre-war appreciations. Malay and Singapore troops backed up the immobile artillery of the Fortress. The 8th Australian Division’s two brigades defended the east coast against Japanese assault. The 3rd Indian Corps set up on the Thai border, against a Japanese invasion of the southern corner of the nation and a drive down Malaya’s west coast. If that happened, the British plan was Operation Matador: to hurl the Indian troops into Thailand and hold “The Ledge,” a hilly outcropping facing potential invaders.

All seemed academic in Singapore—the real war was in Europe and North Africa. Nobody bothered with civil defense precautions, air defense systems, or training troops for the jungle. The 3rd Indian Corps commander, Lt. Gen. Lewis “Piggy” Heath, resented that Percival, a junior officer in peacetime, outranked him. Major General Gordon Bennett, who commanded the 8th Australian Division, resented his own officers, senior officers, British officers, and Percival in particular.

On December 8, 1941, the Japanese preempted the British discussions by invading the Kra Peninsula with three infantry divisions totaling 38,000 men of Lt. Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita’s 25th Army, backed up by swarms of army and navy aircraft, ignoring a monsoon. They stormed into Thailand and south to Malaya.

Now Percival was in the fire, and he proved unequal to the task. British troops were supposed to move north into Thailand to occupy “The Ledge.” Percival dithered. The Indians didn’t move, instead squatting in the rain, awaiting the Japanese. “The Ledge” was taken by the Japanese.

The 11th Division was assigned two roles: offensive and defensive. Percival chose neither. Percival’s own pre-war appreciation said that the RAF airfields built in northern Malaya could not be defended. They were neither defended nor properly abandoned, and the Japanese soon seized them and made use of both their runways and supplies. Brigadier Ivan Simson, Percival’s Chief Engineer, repeatedly pressed the need of building entrenchments in Singapore and anti-tank training for the troops, using bundles of manuals on hand. Percival said that doing so would be “bad for morale.”

Some disasters were beyond Percival’s control. When Japanese aircraft attacked Singapore on the first night of the war, they found the city fully lit. The chief electrician was at the movies with his keys to turn off the power plant, and nobody could find him. Once they did, gas lamplighters had to walk around Singapore, shutting the gas lights off one at a time. RAF fighters that survived the loss of their airfields to the north were soon chopped up by Japanese planes. The only good news was that Brooke-Popham and his mustache were fired and replaced by the capable Field Marshal Sir Archibald Wavell.

Things got worse. Percival could not control the battle. Yamashita’s men took the initiative and took to their bicycles at once, thundering down Malaya’s paved roads. From Fort Canning in Singapore, Percival could not effectively coordinate and communicate with his men. Civilian telephone operators went to lunch or cut his calls, and he made no efforts to rectify the situation. At meetings, Percival arrived tired and worn out, unable to lead. The British official historian summed these conferences up well: “Bennett would…take the floor putting forward impracticable proposals until Heath would break in with a sensible suggestion based on sound military considerations, which Percival would act upon.”

The Japanese moved around road-based British defenses, sloshing through mangrove swamps and thick jungles. When the 11th Indian Division disintegrated at Jitra, historian Arthur Swinson pronounced it “a disgrace to British arms.”

Percival tried to defend the Slim River, hoping to hold it until the 18th British Division could arrive in Singapore, bringing fresh troops, unfortunately trained for desert warfare. Once again, Japanese tanks and infantry blasted the Anglo-Indian defenses, sending the men fleeing in disorganized mobs. The Japanese killed 500, taking 3,200 prisoners and vast quantities of intact supplies.

Blame for this catastrophe fell on Percival’s head for failing to replace the battered and demoralized 11th Indian Division with relatively fresh troops that were still in garrison in Singapore.

After this, Wavell flew to Singapore to find out what was going on for himself and was unimpressed. Wavell found Percival “an uninspiring leader, weak and gloomy.” However, the field marshal could find no replacement, given that the British had already fired a number of division and brigade commanders in Malaya.

Yet Wavell privately told Percival’s subordinates of his lack of confidence in their boss. Nor did Wavell stamp out the bickering between Heath and Percival. Wavell’s only move was to put Bennett and his Australians in northwestern Johore and Heath’s 3rd Indian Corps in southeastern Johore. This, Wavell determined, would be the decisive battle for Singapore. Wavell intended that the Australians, with their aggressive jungle fighting tactics, would buy time for the 18th Division to arrive. However, Percival wanted to fight a more conventional battle and sabotaged Wavell’s plan.

Yamashita attacked the British defenders, who now outnumbered him, relying on air superiority and captured supplies. The Australians fought hard, but the Indian troops less so. The Japanese Imperial Guard Division crushed the 45th Indian Brigade and cut off two Australian battalions, which took heavy casualties in their breakout. Bennett and Heath blamed each other, and Percival made no effort to resolve the debate.

Australian and Indian troops streamed across the Johore Causeway into Singapore Island, joining the 18th British Division already there. Percival had lost 19,123 killed, wounded, and missing, along with vast amounts of supplies. London told Wavell and Percival that Singapore had to be held as long as possible. Australian replacements—some barely trained—were sent to Singapore. They joined other ill-disciplined men in an orgy of looting. Again, Percival failed to act. Wavell again reminded Percival to build trenches on Singapore’s north shore. Again, Percival said they would be “bad for morale.” Nor did Percival build air raid shelters for civilians. He did not act to resolve disputes over pay for coolies to dig them.

Now Percival had to figure out where the Japanese would attack his 220 square miles of flat land. Wavell ordered Percival to deploy the fresh 18th Division at the island’s northwest corner, amid the mangrove swamps, where the Japanese were likely to attack. But Percival’s intelligence officers argued that Yamashita had 150,000 men and 300 tanks—more than double their actual strength—and Percival placed the 18th Division and the best Indian units in the east, leaving the northwest coast to Bennett’s weary or poorly trained Australians.

The Japanese launched their assault on Singapore on February 8, at dusk—against the Australians in Singapore’s northeast corner. They blasted through the exhausted Australians, who gave way after weeks of determined and hopeless defense. Percival overestimated the Japanese attack at 23,000 men rather than the 12,000 it really was. Admiral Jack Spooner, the Royal Navy’s senior officer, “tried to ginger up Percival to send reinforcements from anywhere and risk a second attack as the chances were the Japs wouldn’t know the troops had been moved for some time. But no—he had no fight left.”

Australian leadership disintegrated, too, with one of their brigadiers saying he was going to urge Percival to surrender. Wavell, a firmer voice, flew into Singapore on February 10, and told Percival that his troops outnumbered the Japanese and “the honor of the British Empire and of the British Army is at stake.”

It didn’t help. British Imperial troops deserted and found succor in wine stocks. Japanese troops advanced. On February 13, the top British commanders met at Fort Canning’s air-conditioned “Battle Box,” where Bennett and Heath said that further resistance was futile. “I have my honor to consider and there is also the question of what posterity will think of us if we surrender this large Army and valuable fortress,” Percival said.

Heath had a harsh retort: “You need not bother about your honor. You lost that a long time ago up in the North.”

At 9:30 a.m. on February 15, Percival summoned his commanders for a last meeting at the Battle Box. There was just one day’s supply left of water, gasoline, and artillery ammunition. There was no possibility of a counterattack. Continued resistance would mean death not only for troops but Singapore residents. Percival announced his decision to surrender.

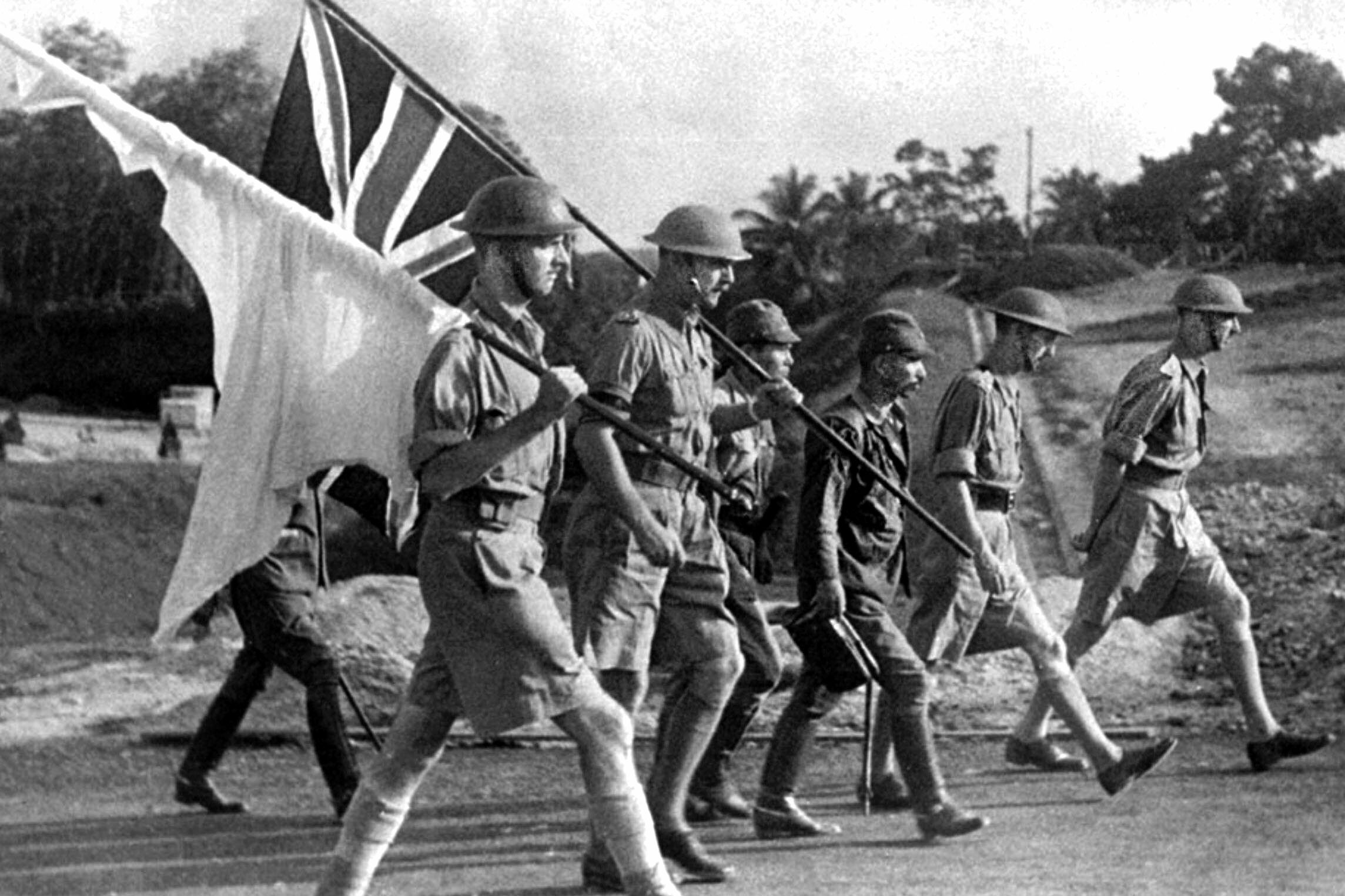

The scenes that followed remain iconic, the tin-hatted Percival, looking dazed, and his defeated party marching out under white flags to the Ford Factory at the Bukit Timah Road to surrender to Yamashita, the angry negotiations in which the Japanese general bellowed “Yes or no?” either at Percival or his own interpreter, and surrendered Australian troops sweeping Singapore’s streets while Japanese troops marched in.

It was the greatest military disaster in the history of the British Empire, and the British lost about 130,000 men, most of them POWs, who would suffer unparalleled cruelty and torture while building the “Burma-Thai Railway.”

Bennett did not go “in the bag”—he fled to Australia, claiming the nation needed his knowledge—but Percival did.

Initially, Percival was held at Changi Barracks, a giant pre-war British Army base, with many of his men. Depressed, he sat quietly outside a small house or walked the camp’s perimeter, accompanied by his former aides, reviewing his ill fortune. The Japanese recruited 10,000 Indians and Sikh prisoners into the Indian National Army, and these renegades served as camp guards, happy to mistreat their old officers. If a British officer failed to salute an INA guard, the guard would set the Briton straight with a beating by a rifle butt. Officers were forced to do menial tasks.

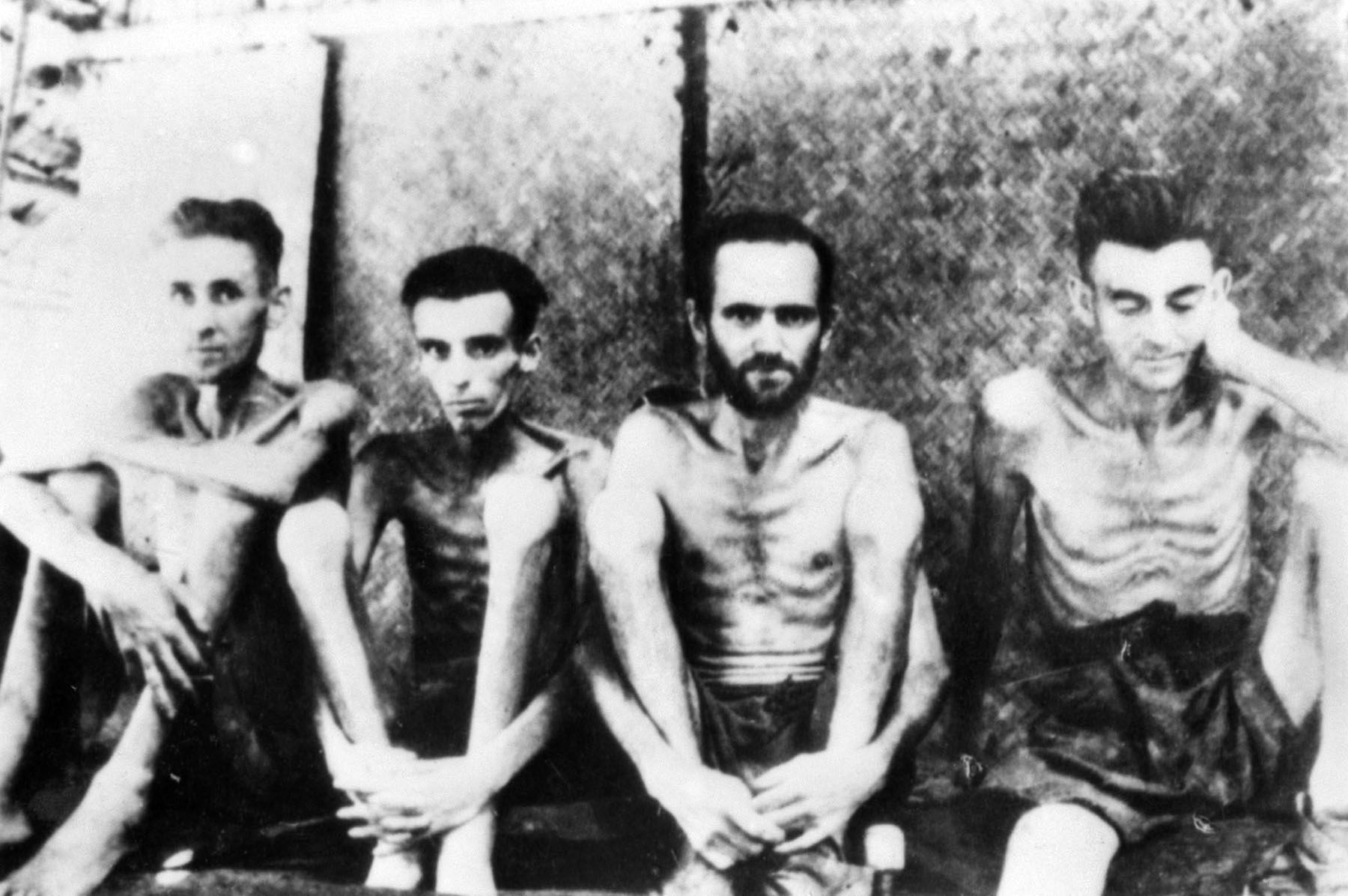

The Japanese also starved their prisoners, seeing them as dishonorable for surrendering.

As senior POW, Percival showed moral courage. He did not oppose the Japanese requirement to salute all guards but stood up for POW welfare, complaining about their inadequate accommodations, rations, and medical treatment. When the Japanese asked Percival for British technicians to repair captured antiaircraft guns, he refused, saying that would be aiding the enemy. The Japanese repeated the threat later, with a similar result. The Japanese threw Percival into solitary confinement for 17 days. Eventually, they simply asked him if he knew where the guns were located. Percival said the Japanese must know where they were as well as he did by now, and that ended the punishment.

When three British artillerymen were caught in a failed escape attempt, the Japanese shot them, though Percival protested that such punishment was illegal.

Percival wrote in his memoirs of the Japanese hypocrisy on hygiene: “They will insist on fingernails being clean, but a fly-covered refuse dump adjoining a kitchen means nothing to them. They seem to have absorbed Western ideas but not how to apply them.”

On August 13, 1942, Percival and other officers and civilian leaders were shipped to Taiwan on the cargo steamer Tanjong Maru. The officers sweltered in the holds, enduring diarrhea and dysentery, with few latrines. The Japanese did little about it, and the suffering did not end until August 31, when the POWs were unloaded and taken to Heito Camp—officially Taiwan POW Camp No. 3—which held American generals bagged in the Philippines, including Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, who had endured the cruel duty of defending and surrendering the archipelago after General Douglas MacArthur was ordered to escape.

The Japanese ordered their captives to sign “no escape” declarations. Aware that British officers were under strict orders from London to make every effort to escape, Percival and his men refused. Percival was marched off to the guardroom. The parade remained formed up for three hours in the rain until sunset.

Percival asked to meet with his men and agreed to the Japanese terms, regarding the document as meaningless. After that, he and his men were sent to their barracks, which had brick walls, palm leaf roofs, and bamboo partitions, with wooden shelves to sleep on—but no mattresses.

The Japanese commanding officer was Lieutenant Tamaki, a vicious sadist who cared little for the welfare of his prisoners. Tamaki provided no medical care. He told them he would “fill the camp cemetery.”

In September, the British and American officers were moved to Karenko Camp in Taiwan, the collecting point for all prominent POWs, including Dutch generals and admirals from the East Indies and Britons from Hong Kong. Despite their high rank, treatment was “disgraceful,” in the words of Hong Kong Governor Sir Mark Young. Senior officers, regardless of age and health conditions, were required to perform manual labor. Percival found himself sharing a room with Simson, one of his old antagonists from Singapore.

Japanese troops treated generals and governors as mere coolies, beating them and slapping them on any pretext. Oddly, the work was not that hard—mostly gardening—but the abuse was continuous and sadistic. Guards would conceal themselves in bushes on the path to the latrine, leap out, and beat senseless a POW who had failed to see and salute them. After that, the guards would stand around laughing at the POW’s plight.

The Japanese appointed Percival “squad leader” for his room, and soon he was fired from that exalted post for constantly standing up to his captors on many issues. He protested everything: living conditions, food, guard assaults, and abuse. The Japanese ignored him.

The food was bad…thin vegetable soup, cooked rice, and occasional meat. Percival and his men wasted away. To supplement their meager diets, the POWs planted vegetables.

In his spare time, Percival took pencil and paper and began writing an account of the Malayan campaign, knowing that London would need it sometime. He had to write it from memory and with the support of his fellow POWs, which led to a lot of rehashings of old arguments.

While this was going on, Japanese officers regularly beat and physically abused the captured generals for refusing to give up secrets in interrogations or cooperate in making propaganda statements.

In late 1942, the Japanese brought in reporters to interview the prisoners, hoping the defeated generals would say that Japan was going to win the war.

Percival and some of his fellow officers, including Wainwright, were taken to the home of the mayor of Karenko for tea. “But then the trick was exposed,” Percival wrote. “Cameras were produced and photographs taken of the Allied prisoners ‘enjoying tea and a smoke in their comfortable quarters.’ That was typical of the Japanese methods.”

Beatings continued—Japanese troops pounded Heath, who was unable to stand at attention due to his withered arm. Percival protested the evil deed and its savagery, and a Japanese orderly officer and sergeant interpreter strode up to Heath. The officer spoke at length in Japanese. The interpreter said, “You have now received an apology.” The two left.

Percival was not frightened of, or cowed by, the Japanese bullying tactics. He met with the camp commandant’s executive officer—the CO never deigned to meet with POWs—and demanded better supplies for all ranks. The Japanese told him that “the sentries were right in beating prisoners and that Japanese internees were being beaten by the English and Americans.”

In addition to fighting the Japanese, Percival also had to stand up to exhausted and physically and mentally weakened POWs who were ready to appease their captors, in an isolated environment, where they had no news of the war or letters from home.

In April 1943, the Japanese moved their prisoners to Tamasata, and astonished their senior prisoners by issuing Red Cross parcels, giving a Swiss Red Cross representative a potted 30-minute tour of the new camp with no opportunity to speak to prisoners individually. But at a conference, Percival told him of their needs.

Thirty minutes after the Red Cross man left, the POWs went straight back to Karenko and a brand new camp for the most senior officers, called Moksak. This camp had a library and a record player “liberated” from a British resident of Taiwan. The commandant pressured Percival and Wainwright to take part in Japanese propaganda films. They refused. The Japanese tried bribery, offering Percival a caged canary as a pet. He let it escape, unable to see another creature in a cage, particularly a bird.

The Japanese offered to let the officers go fishing. They did so, to cope with the monotony, and found a battery of film cameras waiting for them, along with a live fish in a bucket, attached to a rod, to prove they could really catch fish.

The Japanese also let their captives listen to the radio—but the stations were all Japanese. However, the POWs translated the broadcasts and discovered that while the Japanese were winning “tremendous victories,” they were all taking place closer and closer to their homeland, suggesting they were on the retreat.

The propaganda stunts having failed, Percival and his company were moved back to Karenko, where beatings grew worse. Emperor Hirohito declared that Japan’s military situation was “truly grave” on October 26, and prison guards scapegoated their captives.

From there, the POWs moved to Shirakawa, where beatings continued. A Japanese soldier decided a British general was not standing at attention properly and pounded him with his rifle butt. The orderly officer stood by, laughing heartily. Percival wrote that the Japanese “are almost all of them subject to fits of uncontrollable temper. But I would say that the most outstanding characteristics are ignorance of world affairs and narrow-mindedness. Perhaps this is not surprising when one remembers that it is little more than 80 years since Japan emerged from isolation. I believe there were few people in Japan who had any conception of the resources of the Western Powers.”

Beatings were a major menace to the prisoners, but so were health issues, with overflowing latrines and rivers of sewage near the kitchen. More than 60 British and American colonels were ordered to empty the latrines with buckets.

However, by October 1944, the war was finally catching up with Taiwan, and the U.S. Navy and Army Air Forces were subjecting it to regular bombing. The most prominent POWs were moved to the relative safety and bitter cold of Japanese-occupied Manchuria—for fear they might be liberated and tell the truth about the horrors they endured.

Required to take minimal kit, Percival was forced to burn his carefully compiled reports. Now that every Japanese ship moving in the Pacific was a fat target for American submarines, Percival and his colleagues were flown to Sian, near Shenyang (then called Mukden).

As winter approached, the exhausted POWs found that the Japanese had actually thought ahead and provided them with Red Cross parcels. Brutality was replaced with boredom. Percival received his first letters from home, posted years ago, including one from Dill, saying, “I constantly think of you. Do not think that you are forgotten.” Shortly afterward, Percival found out that Dill had recently died.

However, while the Japanese were treating Percival tolerably, if not well, they continued to commit vile atrocities on lower-ranking POWs. Tokyo ordered that they be massacred to prevent the advancing Allies from learning about the mistreatment. At Palawan in the Philippines, Japanese troops hurled gasoline into air raid shelters full of prisoners and set them on fire. On other islands, death marches took care of Australians and Britons.

The war turned into a race for survival between the prisoners and the Japanese, and the U.S. Army Air Forces ended it on August 9, 1945, dropping the second atomic bomb on Nagasaki. Simultaneously, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, and millions of battle-hardened Russian troops stormed into Manchuria. This double whammy forced Emperor Hirohito to accept the Allied unconditional surrender demands, which included, in writing, the unharmed release of every single remaining Allied POW, from Percival to the lowest-ranking private. Japanese generals ordered their camp staff to turn over the facilities to their captives, burn records of atrocities, and order guards who had committed the gravest crimes to shed their uniforms and flee Allied retribution.

Now came the hard part of evacuating exhausted, sick POWs from Japanese camps across the Pacific. Japanese generals, summoned to American-held Okinawa to organize the occupation of the homeland, were ordered to bring complete lists and particulars of the camps.

On August 16, 1945, Percival and fellow prisoners saw planes fly over and parachutes drift down near their camp. The Japanese provided no information. That evening, six armed white men in unfamiliar uniforms arrived at the camp, went straight to the guardroom, and met with Japanese officers. After that, the Japanese relaxed their tight discipline in the camp, and prisoners were allowed to walk around all night, smoke, and even take cigarettes from sentries.

At 7 a.m. the next day, the Japanese commandant summoned the top Allied officers and told them the Empire had signed an “armistice” with the Allies on August 15. Even now, the Japanese could not use the word “surrender.”

The six parachutists were a team from the American Office of Special Services, sent in to care for the POWs and ensure their safety.

The U.S. Army Air Forces began parachuting containers of food, clothing, and medical supplies to camps throughout Manchuria, and a more authoritative form of liberation came when Soviet tanks crashed through the gates of many prison camp and English-speaking Russians offered to kill any Japanese guards who had mistreated Allied POWs.

Percival was flown to Chongqing (then Chungking) on August 27, where he was greeted by General Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart, Britain’s liaison officer to China. In a fresh uniform, the gaunt Percival was flown to Tokyo, where he stood by Wainwright on the deck of the American battleship USS Missouri, behind General MacArthur, as the Supreme Commander Allied Powers signed Japan’s surrender with six pens. MacArthur gave the first to Wainwright, the second to Percival.

Percival’s next stop was the Philippines, where he sat across the table while his old nemesis, Yamashita, surrendered the archipelago he had defended to the Americans. When the Japanese general entered the room, a half-smile flickered across his face.

That was the end of Percival’s military career. He flew home to write a long dispatch for the War Office on his defeat, posed for the press with his wife and MacArthur’s pen, and wrote his memoirs, The War in Malaya. However, unlike the Americans, who hailed men like Wainwright as heroes, the British offered Percival neither promotion nor a knighthood.

Government ministers and historians alike found much fault in the general’s conduct: he had shown very little personal leadership, made bad, poor, or no decisions; and crumbled under pressure, defeated by an army he outnumbered three to one. Admittedly, Percival’s force was poorly trained, badly equipped, and not motivated, so that even a Slim or a Montgomery would have had a difficult time leading the motley crew, but Percival was a weak man playing a weaker hand.

One group of men never lost faith in Percival—that was the survivors of his command, now the Far East Prisoners of War Association (FEPOW), who elected him their Life President as FEPOW No. 1. They remembered how he had stood up for their welfare against the Emperor’s sadists.

In the 1950s and 1960s, he did the same, advocating tirelessly for medical benefits and compensation for his men. The Japanese finally paid each POW a measly £1,500, hardly enough for a lifetime of suffering the after-effects of starvation and beatings. In 1991, with most of the surviving FEPOWs dead, Prime Minister Tony Blair paid the remainder £10,000 each. The FEPOWs were bitter that the money did not come from Japan, but from British taxpayers—including themselves.

Percival was not present to see this bizarre finale. He died on January 31, 1966.

Author David Lippman resides in New Jersey and writes frequently on a variety of topics for WWII History.

Nothing surprising here: Percival was a bully, a coward (WWI decorations awarded by fellow aristocrats notwithstanding) and absolutely incompetent as a commander. He and his brutal and undisciplined Essex regiment terrorized civilians during the Anglo-Irish war. He was known to have personally applied sadistic tortures to captured or suspected Irish resistance fighters. What goes around comes around.