By John Wukovits

President Franklin D. Roosevelt sat in his White House study, an aging leader suddenly appearing older and wearier. Only moments before, the Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, had informed him that much of the Pacific Fleet stationed in Hawaii now rested on Pearl Harbor’s bottom. Carrier aircraft from Japan had executed a devastating surprise blow to the U.S. military. Doubt and disbelief blanketed Roosevelt’s face.

The Secretary of Labor, Frances Perkins, could see the anger and dismay. “It was obvious to me that Roosevelt was having a dreadful time just accepting the idea that the Navy could be caught unawares,” she recalled.

The leader who had lifted the nation’s morale in the bleakest days of the Depression quickly rallied. With fire in his eyes and determination ringing in his words, Roosevelt vowed to gather the remaining forces and fight on until America’s factories could produce the weapons needed for the United States to emerge victorious from the conflict. As he wrote British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, “We must constantly look forward to the next moves that need to be made to hit the enemy.”

He wanted one of those moves to target the Japanese homeland. Roosevelt believed that such a strike would not only inflict a stunning blow to the enemy, but would also boost American morale at a time when it most needed a lift. Almost daily, Roosevelt prodded his top military leaders into finding some way to take the war directly to the Japanese.

He had his answer by January 10, 1942. Captain Francis S. Low, a member of the staff of Admiral Ernest J. King, the commander-in-chief of the U.S. Fleet, mentioned the revolutionary idea to King of bombing Japan by launching bombers from aircraft carriers. As he took off from a Norfolk, Va. airfield, he explained, “I saw the outline of a carrier deck painted on an airfield which is used to give our pilots practice taking off from a short distance. I saw some Army twin-engine planes making bombing passes at this simulated carrier deck at the same time.” Low put the two ideas together and rushed to King’s office once he landed in Washington, DC. He knew that bombers possessed the required range that fighters did not, and if carriers could take them close enough, they might be able to lift off and bomb Tokyo.

King liked the idea and ordered Low to discuss it with other top officers. By late January a tentative plan had been drawn up, and the head of the Army Air Corps, General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, called to his office the man he had selected to organize the operation.

Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle’s place in aviation history had already been assured by the time World War II erupted. A veteran test pilot, Doolittle established numerous flight records in the 1920s, including becoming the first pilot to cross North America in less than 24 hours. Arnold often sought his counsel in aviation matters, and he now asked the veteran pilot, “Jim, what airplane do we have that can take off in 500 feet, carry a 2,000-pound bomb load, and fly 2,000 miles with a full crew?” As Doolittle thought, Arnold added that the aircraft should be able to take off in a space only 75 feet wide. Doolittle responded that only one such plane existed—the North American B-25 Mitchell medium bomber.

Arnold then divulged the details of the mission he wanted planned. Army bombers would take off from aircraft carriers, bomb Japan, then fly on to airfields held by friendly Chinese forces under the command of General Chiang Kai-shek. He stressed that Doolittle was too valuable in Washington for him to actually lead the operation, but he wanted Doolittle to supervise its planning. Doolittle agreed and left to begin piecing together the mission.

Thousands of miles from Washington, DC, Admiral William F. Halsey walked into a room at the Pacific Fleet’s headquarters in Hawaii for a meeting with Rear Adm. Donald B. Duncan. Duncan informed Halsey of the daring Doolittle operation and asked if Halsey felt the plan could work. The aggressive carrier leader, known for never shrinking from any challenge, agreed it might be possible, but added, “They’ll need a lot of luck.” He then agreed to take the bombers within range and launch them against the enemy.

Halsey subsequently met with Doolittle to discuss the mission. They agreed that Halsey would transport the Army bombers to within 400 miles of Japan unless discovered before reaching that takeoff point. In that event, they would launch for an attack if they were still within range of Tokyo and had enough fuel to later ditch at sea. If they were discovered outside the range of attack, the bombers would be flown to either Midway or Hawaii, or if not in range of any land bases be shoved overboard so the carrier Hornet’s flight deck could be used by its complement of fighters.

Doolittle realized how important this mission could be to the war effort. Japan had never been assaulted by a foreign invader, and Tokyo assured its citizens that they had little to worry about concerning an attack on the homeland. A successful bombing raid over Japan would demolish the myth of invincibility that comforted the Japanese. At the same time, the mission would energize an American public too accustomed to military disaster. Doolittle wrote, “America had never seen darker days. Americans badly needed a morale boost. I hoped we could give them that by a retaliatory surprise attack against the enemy’s home islands launched from a carrier, precisely as the Japanese had done at Pearl Harbor.”

On March 3, 1942, Doolittle met with close to 140 pilots and crew members at Eglin Field in Florida. The men had volunteered to train with Doolittle even without knowing the details of the mission, and Doolittle could not divulge much more. He explained that the mission for which they had volunteered “will be the most dangerous thing any of you have ever done. Any man can drop out and nothing will ever be said about it.” He cautioned against discussing their work with anyone, even among themselves, and that “the lives of many young men are going to depend on how well you keep this project to yourselves.”

While the group practiced launching bombers from restricted distances for the remainder of the month, Doolittle tried to change Hap Arnold’s mind about his exclusion from leading the bombers to Japan. Doolittle was supervising the most exciting U.S. mission yet to come out of the war, and he was not about to be pushed to the sidelines after training. He met with Arnold in mid-March, when Arnold agreed that if his chief of staff, Brig. Gen. Millard F. Harmon, Jr., assented to Doolittle’s participation, he would also.

Arnold never intended to permit Doolittle to go along and only answered in this manner to get him off his back. He planned to communicate over a squawk box with his chief of staff and tell him not to give the flier permission before Doolittle walked down to his office, but Doolittle sensed what Arnold was doing. He raced over to Harmon’s office before Arnold had a chance to call, told Harmon that Arnold said it was all right for him to go on the mission as long as Harmon thought it was fine, and received permission. As Doolittle left, he heard Arnold’s angry voice over the squawk box admonishing his chief of staff.

Back at Eglin, Doolittle’s crews solved a few minor problems that arose. Some worried over the absence of tail guns in the bombers, which would hand enemy fighters an easy avenue of attack. One pilot suggested they install in each tail two broomsticks painted black, figuring that from a distance the mock guns would appear real. To increase the planes’ range, mechanics added three extra fuel tanks, including a 60-gallon tank that replaced the bottom gun-turret mechanism and a collapsible 160-gallon tank placed in the crawlway.

Doolittle had difficulty solving another issue. Civilian mechanics worked far too leisurely to suit the officer, but he could not tell them why they had to increase the pace of their efforts because of the mission’s top-secret status. Doolittle contacted Arnold and said, “I’d appreciate it if you would light a fire under these people. They’re treating this whole project as ‘routine’ and that won’t get the job done.” A single telephone call had the desired results.

On March 23, Doolittle announced the names of the 80 members selected for the 16 bombers. Each aircraft carried a pilot, copilot, bombardier, navigator, and gunner. He thanked those not chosen and cautioned them against mentioning their work to anyone at home. To those remaining, he explained that they would soon be aboard a carrier and on their way, but he could not yet let them in on the mission’s details.

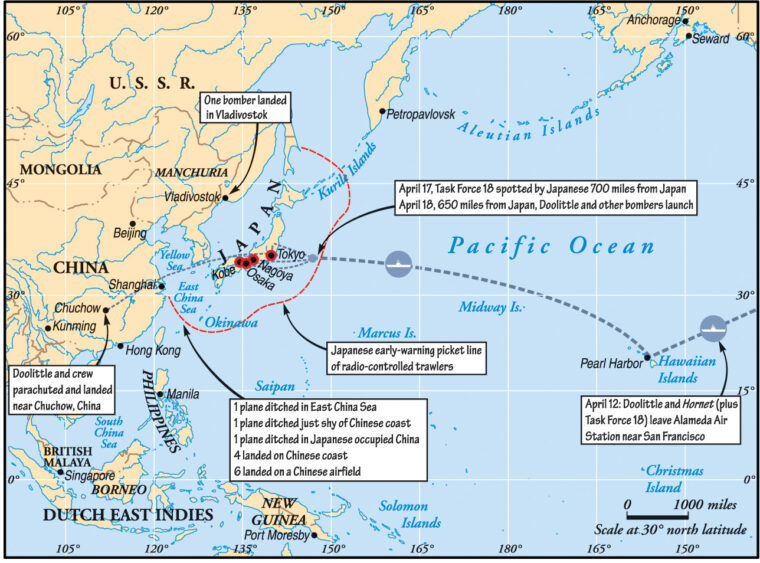

On April 2, Hornet departed from Alameda Air Station near San Francisco, accompanied by two cruisers, four destroyers, and one oiler. Gleaming on her decks, in plain view of civilian spectators along the shoreline, stood the 16 B-25 bombers to be used for the mission. They were being ferried, so military authorities explained to the press, to Hawaii. The aircraft so packed the carrier’s deck that the tail of the last bomber protruded over the stern of the ship.

Once safely aboard and away from shore, Doolittle gathered his men and divulged the complete details. As the excited crew members listened, Doolittle explained that the 16 bombers, led by himself in the first plane, would approach Japan over a 50-mile-wide front and blast targets in Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe. They would then fly on to Chinese airfields alerted to receive them. Doolittle ended his talk by giving each man another opportunity to drop out of the dangerous operation, which everyone hastily declined.

As Doolittle met with his men, the commander of the task force shuttling the bombers to the Pacific announced the purpose of their excursion to his naval personnel. Doolittle recalled, “Cheers could be heard all over the ship.” Navy seamen and officers realized they were finally getting a crack at the enemy right in the heart of his homeland.

The first half of the trip across the Pacific proved uneventful. Doolittle had to correct some of his crew members one day when he overheard them talking about bombing the Japanese Emperor’s palace. He emphatically warned against hitting either the palace, residential areas, hospitals, schools, and other nonmilitary targets. “There is nothing that would unite the Japanese nation more than to bomb the emperor’s home,” he asserted.

Otherwise, Doolittle liked what he saw about the men. The few spare crew members who had been brought along in case of illness or injury to the others repeatedly tried to convince those going to trade places with them, but they received no takers. Doolittle sensed an urgency in the young men’s looks and actions, a determination to make this mission count.

As they steamed toward Hawaii, another task force headed out of Pearl Harbor to take up escort duty with Doolittle. Commanded by Halsey, Task Force 16’s two heavy cruisers, four destroyers, and one oiler flanked the aircraft carrier Enterprise. The unit was to rendezvous with Hornet and Task Force 18 and escort them to the launching point.

The two forces merged off Hawaii on April 13 and set course for Tokyo. Doolittle’s men attended lectures on such items as sanitation and meteorology, practiced shooting at kites, honed their navigation skills with the Hornet’s navigator, and played card games.

To enjoy the best odds for success, the ships had to arrive at the launching point 400 miles off Japan’s coast without being detected. However, signs indicated the enemy may have picked up traces of the plan by April 16. On that day some of Halsey’s men monitored a Tokyo radio broadcast scoffing at a British news story that three American bombers had dropped bombs on Tokyo. “This is a most laughable story,” declared the Japanese transmission. “They know it is absolutely impossible for enemy bombers to get within 500 miles of Tokyo. Instead of worrying about such foolish things, the Japanese people are enjoying the fine spring sunshine and the fragrance of cherry blossoms.” Doolittle worried that the erroneous report would place Japanese forces on high alert to counter such a possibility.

One day later, while still 700 miles from Japan, Enterprise’s radar spotted two ships 12 miles away. Halsey changed the task force’s course and evaded the vessels, but the contact caused concern that they would be discovered long before arriving at the launching point. Later in the day a search patrol plane sent word that it might have been seen by a small boat below, and shortly afterward lookouts on the Hornet sighted another ship.

What they had seen were Japanese ships that formed a picket line established by Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto 600 to 700 miles out to sea as an early-alert network to warn of approaching American forces. Aboard the Nitto Maru, Seaman Second Class Nakamura Suekichi awakened the ship’s captain, Gisaku Maeda, to inform him, “There are two of our beautiful carriers now dead ahead.” The captain hurried on deck, looked through binoculars in the direction of the sighting, then said, “Yes, Suekichi, they are beautiful but they are not ours.”

More ships appeared when they had sailed only six miles farther. Halsey ordered his cruisers to sink the vessels to prevent transmissions to Japan, but they overheard one of the ships sending an alert to Tokyo. All doubt about their existence had now been removed, placing a difficult decision in Halsey’s lap. Despite being 650 miles from Japan, Halsey knew he either had to immediately launch the bombers—even though the longer range might preclude most aircraft from reaching safety in China—or turn back. Halsey called Doolittle and ordered the planes into the air on April 18.

Doolittle and his crews rushed about the Hornet to ready their planes for the long trip. Captain Marc A. Mitscher handed Doolittle five medals given to different officers by the Japanese government during an earlier voyage to Japan, and asked that they be attached to the bombs and returned. Crewmen scribbled messages in chalk on the bombs stating, “I don’t want to set the world on fire, just Tokyo,” and “You’ll get a bang out of this!”

Doolittle held a final briefing with his men during which he again asked if anyone wanted out. No one did. One man wondered what to do if shot down, and Doolittle replied, “I don’t intend to be taken prisoner. I’m 45 years old and have lived a full life. If my plane is crippled beyond any possibility of fighting or escape, I’m going to have my crew bail out and then I’m going to dive my B-25 into the best military target I can find. You fellows are all younger and have a long life ahead of you. I don’t expect any of the rest of you to do what I intend to do.”

The 80 men removed pieces of identification, letters, or diaries that linked them to the Hornet in case of capture. After placing them in self-addressed envelopes for mailing at a later date, they grabbed their gear and hurried toward their bombers.

Halsey sent a message to the Hornet reading, LAUNCH PLANES X TO COL. DOOLITTLE AND GALLANT COMMAND GOOD LUCK AND GOD BLESS YOU. As noted Hollywood director John Ford set up cameras to record the historic moment, Doolittle prepared to be the first off. A stiff wind buffeted his bomber, and seas intermittently stormed over the carrier’s ramps, but Doolittle stared with fierce determination at the brief distance separating him from the ship’s edge. He knew everyone on deck, as well as his fellow pilots, was watching. If he failed to successfully lift off, the effect could be catastrophic. As he wrote in his memoirs, “If I didn’t get off successfully, I’m sure, many thought they wouldn’t be able to make it either.”

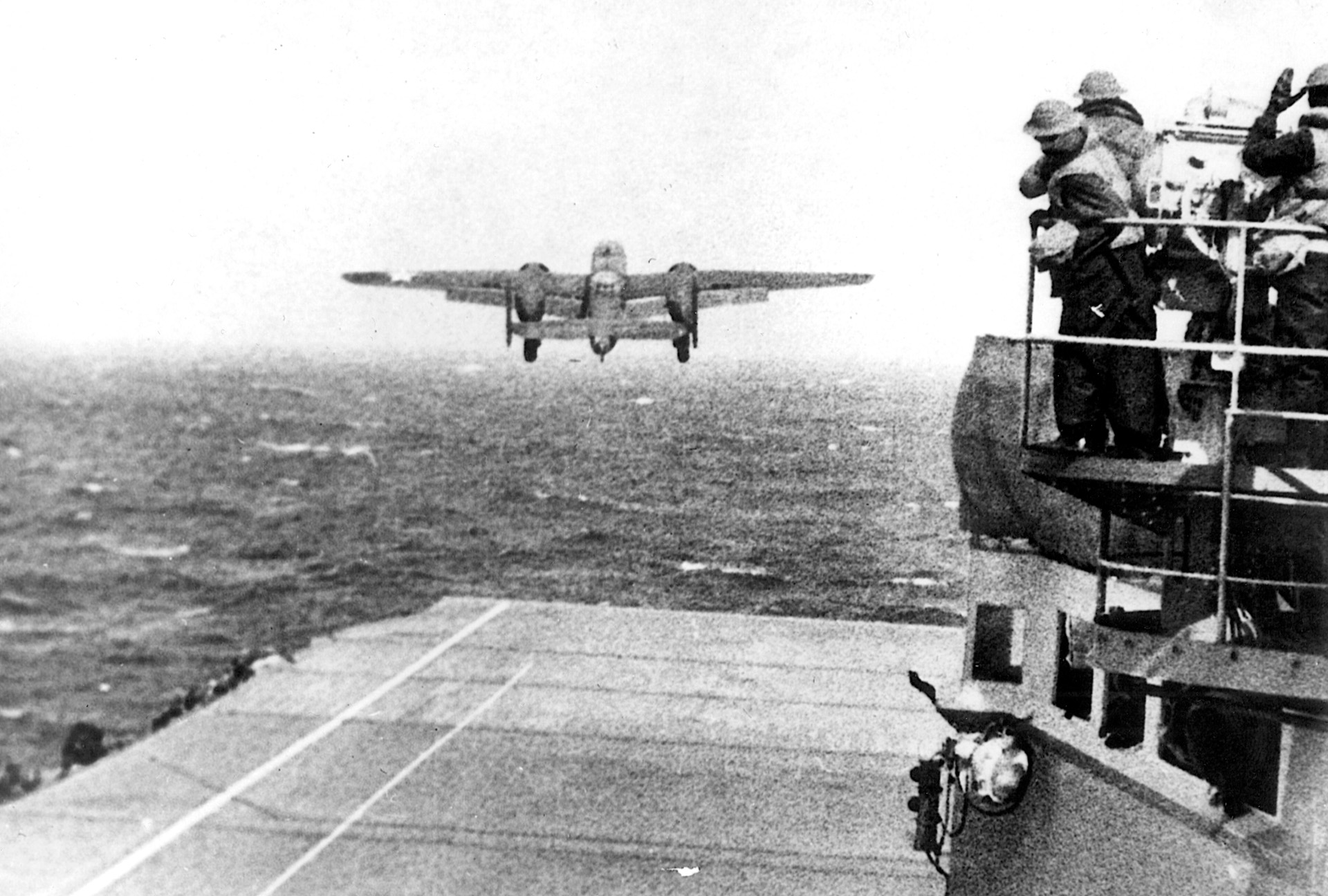

At 7:20, Doolittle flashed the thumbs-up signal to the deck launching officer indicating he was ready. Crew members pulled the chocks away from his wheels; Doolittle nudged the throttle forward and waited for the deck to lift upward in the heavy swells, then released his brakes and lurched ahead. He steered the aircraft down the white line that had been painted along the carrier deck so he would not scrape the bridge with his wing and lifted into the sky with room to spare. Doolittle circled low over the carrier while the crew waved and cheered, then turned toward Tokyo.

The other 15 B-25s followed in quick order. Only the final plane experienced any difficulties. As it taxied into position, a member of the Hornet’s crew, Seaman Robert W. Wall, slipped and was blown by the preceding plane’s blast into the propeller of the 16th aircraft. Other deck hands quickly took him below for medical help. An arm was badly mangled. Wall survived, but the incident rattled the bomber’s pilot. Momentarily distracted, the pilot accidentally put his flap-control lever in retract instead of neutral. Instead of a smooth takeoff, the plane sputtered forward, lifted off the carrier, then plunged seaward. Witnesses expected the plane to crash, but somehow the pilot regained control barely above sea level, gained altitude, and chased after the others already on their way to Tokyo.

The Japanese expected an air attack because of the earlier sightings, but they concluded it could not occur until the next day. The American carriers, they thought, would have to pull within the short range required for fighters, about 300 miles off Japan, and before that time a strong welcoming force under Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo would intercept them. Such a strong conglomeration—90 fighters, 116 bombers, two flying boats, 10 destroyers, six heavy cruisers, five carriers, and nine submarines—headed out for a confrontation that, had Halsey continued to even the original 450-mile launching point, he might not have escaped. Had he lost the two precious carriers, half the remaining U.S. carrier power in the Pacific, the war’s fortunes could have taken a disastrous turn.

The Japanese never located the Americans. They searched for Halsey as he raced back to Pearl Harbor, coming so close a few times that the aircraft registered on the Enterprise’s radar, but they never found him. Halsey refrained from sending aircraft against the search planes because he did not want to reveal his position.

The American admiral heard one welcome piece of information. Each ship tuned its radios to monitor Tokyo broadcasts, and as they listened to one propagandist praising the nation’s navy for keeping enemy forces away from its shores, the sounds of air-raid sirens could be clearly detected. Halsey knew that Doolittle had arrived over the target.

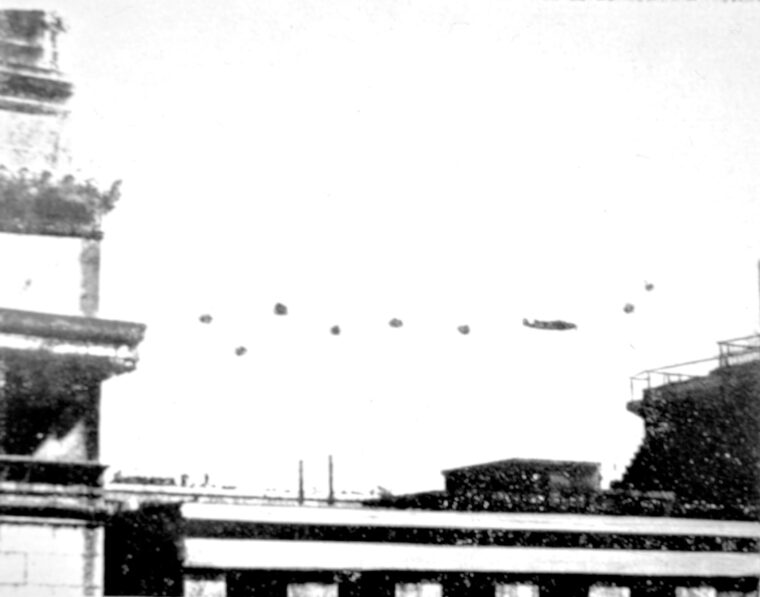

The American bombers experienced an easier time than expected. A Japanese patrol plane sighted a portion of the squadron, but officials in Tokyo discounted the report. Doolittle flew over the Japanese coast 80 miles north of Tokyo, dropped to treetop level, veered south, and sped toward the capital while Japanese men and women on the ground waved toward what they assumed was a friendly aircraft. Doolittle arrived over Tokyo shortly after its citizens had gone through one air-raid drill, and they now assumed that the bombers that suddenly appeared were just a part of another drill.

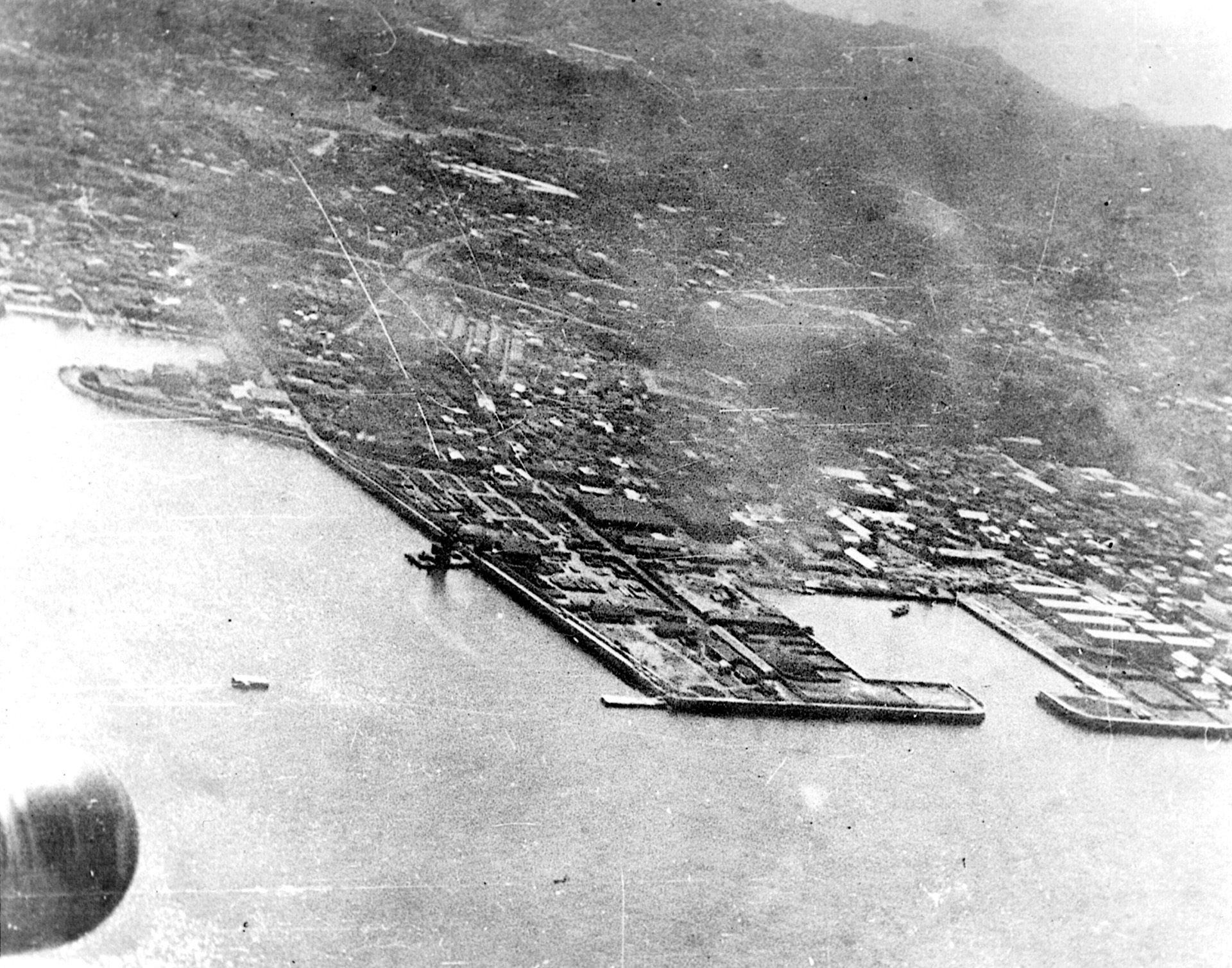

As he neared the city at 12:30 pm, Doolittle pulled up to 1,200 feet and dropped his bomb load on some large factory buildings. As he recorded in his log, he then “lowered away to house tops and slid over western outskirts into low haze and smoke. Turned south and out to sea.” Against surprisingly light opposition, Doolittle had invaded the deepest recesses of Japan’s capital city and hit targets mere miles from the Imperial Palace. The other 15 bombers achieved similar results and headed for airfields in China, praying that they had enough gasoline to reach their destinations.

After evading five enemy fighters that apparently failed to spot him, Doolittle flew across to China, where he climbed to 8,000 feet because of mountainous conditions, fog, and rain. With gasoline tanks running perilously low, he attempted to contact an airfield at Chuchow, but repeated efforts met only silence. Somewhere in the foggy conditions below lay his destination, but without a homing beacon to guide him in he was flying a blind aircraft. Doolittle had no choice but to abandon the plane and hope he and his crew landed in territory held by friendly forces.

As the gauges neared the zero mark, Doolittle placed the bomber on automatic pilot, remained inside while the other crew members parachuted, then jumped. He worried that a hard landing might injure his ankles, which he had broken in an earlier accident, but a soft touchdown in a rice paddy alleviated his fear. He did not feel as comforted as he could have, though, because animal waste blanketed the terrain.

Doolittle knew he could not locate the other crew members in the dark, so he found a water mill in which he took refuge for the night. He had trouble sleeping due to the intense cold, so he performed a series of calisthenics all night to keep warm. When daylight broke, he left the water mill and cautiously approached the first Chinese he saw. The individual led Doolittle to a Chinese major, who gave him food and a place to rest.

The Chinese reunited Doolittle with his crew, who had landed nearby, and the group boarded a boat to Chuchow. There they met an American named John Birch, a young missionary familiar with the Chinese language, who traveled with the men through Communist-held territory into land controlled by Chiang Kai-shek, and on to Chungking to meet with Colonel Claire Chennault, the commander of American aviation forces in the region.

On April 30, Doolittle and his men met Chiang Kai-shek in his palace. “We wore a varied assortment of coveralls, leather jackets, and khaki uniforms spattered with mud and grease,” Doolittle later wrote in his memoirs. Their dress hardly mattered to the assembled dignitaries, who welcomed them as heroes. Chiang Kai-shek presented medals to each of the Americans.

Although he received a warm welcome from the Chinese, Doolittle worried that his superiors back home, as well as the American public, considered his raid a failure. He knew nothing of what had happened except to his aircraft, and he thought if the other 15 crews encountered heavy opposition en route, were shot down, or captured by the Japanese, the raid would show nothing for the tremendous efforts exerted.

One day in China, he discussed the issue with crew member Paul Leonard, who asked Doolittle what he thought would happen when they returned to the United States. “Well, I guess they’ll court-martial me and send me to prison at Fort Leavenworth,” he replied. Leonard listened for a moment before disagreeing. “No, sir. I’ll tell you what will happen. They’re going to make you a general. And they’re going to give you the Congressional Medal of Honor.” Doolittle appreciated the encouraging words but still believed that he would be seen as a failure. “I felt lower than a frog’s posterior,” he wrote.

Most of Doolittle’s men safely made their way back to the United States. One plane, piloted by Captain Edward York, landed in Vladivostok in the Soviet Union when he decided the bomber lacked enough fuel to reach China. Since the Soviet Union was not then involved in the war against Japan, authorities detained the men and held them for the rest of the war.

The other 14 bombers crash-landed in China. Three men died, the Japanese apprehended eight, and the remainder escaped to friendly lines.

Japanese military and political officials suffered extreme embarrassment over the raid. After repeated assurances to their Emperor and countrymen that the enemy could never violate home soil, a daring raid had brought war to their doorsteps. Admiral Yamamoto felt such deep shame that he retired to his room and placed command in the hands of his chief of staff, Admiral Matome Ugaki. Ugaki later scribbled in his diary, “Today the victory belonged to the enemy.”

The Japanese could not immediately retaliate against the Americans, but they vented their anger toward innocent Chinese men and women. Japanese soldiers scoured the Chinese countryside seeking the Americans, leaving a trail of smoking, ruined villages in their wake. Raped women and bayoneted or beheaded men littered the roads and paths. An irate Chiang Kai-shek informed President Roosevelt that the Japanese searched 20,000 square miles of territory and slaughtered 250,000 Chinese.

The vicious response terrified the local Chinese. The Japanese killed one man’s three sons and his wife, and drowned all his grandchildren before killing him. When they apprehended another Chinese farmer who had helped the Americans, they wrapped him in a gasoline-soaked blanket and forced the farmer’s wife to ignite it.

Some of the eight captured Doolittle raiders faced similar treatment. All eight were tortured in various ways in efforts to obtain information on the surprise attack. The Japanese placed bamboo poles behind their legs and forced them to squat for hours on the floor. They rammed large amounts of water down their throats, stretched them on the floor, then jumped on their stomachs. Finally, on May 22, the eight relented, gave details of the mission, and signed a document confessing to war crimes.

A mock trial in August found the eight guilty and sentenced them to death, but it was not until October 14 that the men learned who, indeed, had been selected to pay with their lives—Dean Hallmark, William Farrow, and Harold Spatz.

In letters home the three were permitted to write, the condemned poured out their final thoughts. “I hardly know what to say,” penned Hallmark to his mother and sister in Dallas. “I am a prisoner of war and I thought I would be taken care of until the end of the war. I did everything that the Japanese have asked me to do and tried to cooperate with them because I knew my part in the war was over. Try to stand up under this and pray.”

Harold Spatz reminded his father in Kansas of the love he felt for him and that he “died fighting for my country like a soldier.” William Farrow asked his mother to keep her spirits up and mentioned, “I will see you again in the hereafter.” He then thanked his fiancée for bringing love into his life.

On October 15, a Japanese firing squad executed the three men. The other five Americans spent the remainder of the war in prison, during which two died. When Admiral Halsey learned that three men had been executed, his face turned red with anger. According to an officer standing near Halsey, “He stuck out that ram-bow jaw and he ground his teeth. Those eyebrows of his began to flail up and down. All he could choke out was, ‘We’ll make the bastards pay! We’ll make ’em pay!’”

Jimmy Doolittle arrived in Washington, DC, on May 18. A waiting car sped him to the Pentagon for a meeting with Hap Arnold, then the two walked to General George C. Marshall’s office to debrief the Army chief of staff.

Unknown to Doolittle, Arnold arranged for his wife to be flown to Washington and taken directly to the White House. Arnold, Marshall, and Doolittle drove over to the president’s residence, where they informed a stunned Doolittle that Roosevelt was about to award him the Medal of Honor. Doolittle had barely absorbed this information when his wife, Josephine, walked into the room. The two hugged and spoke a few words, then walked into the Oval Office to meet Roosevelt. An excited president congratulated Doolittle for raising the nation’s morale, pinned the medal on his uniform, then asked Doolittle to say a few words. As Doolittle later remembered, “I felt then and always will that I accepted the award on behalf of all the boys who were with me on the raid.”

Although the damage inflicted was relatively minor, 90 buildings damaged and 50 civilians killed, the Doolittle Raid produced magnificent results. The Japanese military command hurriedly altered plans in the Pacific. Troops meant for other destinations instead headed for China to hunt for air bases in the region, and four fighter groups were shifted from outlying Pacific air bases to the home islands.

Most important, all opposition in the Japanese High Command to Yamamoto’s next major offensive, against Midway in June 1942, disappeared. Scheduled operations to seize Samoa, Fiji, and New Caledonia in the South Pacific, which could have seriously hampered the American effort by severing lines of communication with Australia, were postponed so that the Imperial Japanese Navy could muster its strength for the massive Midway attack. In their desire to redeem national honor and wreak vengeance on the Americans, the Japanese hastily implemented a plan at Midway that proved complex and cumbersome and helped lead to a decisive defeat from which Japan never fully recovered.

In the United States, morale soared with news of the event. A Los Angeles Times headline read, DOOLITTLE DO’OD IT, and the public basked in the glow of one of the few bright spots to emerge from the early days of the Pacific war. When asked in his first press conference after the raid from where the bombers had come, President Roosevelt humorously replied Shangri-La, the fictional paradise that was the subject of a recent popular novel. The country regained optimism that its military forces could fight back, that the nation had something with which to fight back, and that it would eventually succeed.

The Doolittle Raiders have long been remembered for their gallant efforts in April 1942. The military bestowed various honors on the men, including promoting Doolittle directly to brigadier general. Hollywood produced a noted movie about the mission, Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, and veterans from the group are frequently asked to speak to schoolchildren and military gatherings.

Each April 18, on the anniversary of their raid, the surviving Raiders gather for a reunion. Waiting in a room are 80 silver goblets flown in from their trophy case at the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colo., each cup bearing the name of one of the 80. The survivors drink a toast to those who have died, then invert the cups of the men who passed away in the past year.

Only a handful of men remain. Doolittle died in 1993, and each year the list of those alive dwindles. What will not be forgotten is the contribution they made to victory when their nation was down. They picked it up and showed that the American fighting spirit would prevail.

John Wukovits is a veteran writer on WWII in the Pacific and is the author of several books, including a biography of Admiral Clifton A.F. Sprague.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments