By Duane E. Shaffer

The road to Fort Driant began for the United States Third Army when it landed on Utah Beach at 3 pm on August 5, 1944. The Third Army had been activated four days earlier in England under the command of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr.

The four corps that made up the Third Army were VIII Corps under Maj. Gen. Troy H. Middleton, XII Corps under Maj. Gen. Gilbert R. Cook (later replaced by Maj. Gen. Manton S. Eddy), XV Corps under Maj. Gen. Wade H. Haislip, and XX Corps under Maj. Gen. Walton H. Walker. Walker was one of Patton’s personal favorites, and he once said of Walker, “He will apparently fight anytime, anywhere, and with anything that I will give him.” That opinion would be put to the test during the Lorraine Campaign that autumn.

Once the army became operational, it did not take Patton long to engage in the hard-driving cavalry tactics that he loved best. The Third Army was able to break out of the French hedgerow country and by August 20 had entered Argentan just southeast of Falaise. The only part of Third Army that was tied down was the XV Corps fighting against the tough German defensive positions in Brittany.

On August 25, the 80th Division began its move to eastern France with an advance of 280 miles in one day. The division then concentrated around Collemieres and two days later crossed the Seine, Aube, and Marne Rivers. By the end of August, the XII Corps had advanced to the high ground east of the Meuse River near St. Mihiel. This place had special significance for Patton because he had been wounded there during World War I. Problems began for the Third Army when Patton was informed by General Omar Bradley, who commanded 12th Army Group, that there would be no more gasoline shipments until September 3. For a highly mobile army like Patton’s, this became a problem of catastrophic proportions. A total of 400,000 gallons of gasoline had been requested and only 32,000 delivered. This shortage alone was enough to bring Patton’s eastward advance toward the frontier of the Third Reich to a standstill.

Combined with the increasingly bad weather in early September, the gasoline shortage allowed the Germans time to build their defenses in front of the Third Army. As Patton’s offensive operations gradually slowed, German counterattacks on Third Army’s flanks increased. It was apparent that the Germans were in a full fighting withdrawal. Their operations focused on defending and delaying actions while units of all types were massing in their rear. Remnants of the German Army were now engaged in delaying actions east of the Moselle River and concentrated armored counterattacks against Third Army’s bridgeheads.

After these attacks were blunted by the Third Army, Hitler replaced Col. Gen. Johannes Blaskowitz as commander of Army Group G with the tough campaigner from the Eastern Front, General Hermann Balck. Hitler had considered Blaskowitz too passive and favored Balck, who, having many of the same characteristics as his adversary Patton, would conduct an aggressive and ruthless campaign against the Americans. Balck, as an ardent Nazi, was more than willing to carry out his Führer’s directives. Instead of fleeing to the West Wall (Siegfried Line), he dug in around Metz and the Moselle and Seille Rivers. He was prepared to make the Americans pay for every yard.

Third Army’s intelligence section had already determined that the Germans intended to make the most of the ring of forts around Metz, the ancient gateway city through which so many invading armies had passed. Metz was to be the linchpin in the Germans’ defensive strategy. An army had not directly taken Metz since 1552. It had been captured after a 54-day siege during the Franco-Prussian War and had been fortified by the Germans in World War I. However, after the Great War the string of fortresses were left in ruins.

When it became apparent that the Allies were going to plunge through France, the fortresses were reoccupied and slightly renovated. They would provide security for the retreating German armies and the advance of the Allies. Metz was to be Balck’s anchor for the German Line of defense that paralleled the Siegfried line to the west.

With the Allied advance literally stopped cold, Patton decided, against his own better judgment, to test the defensive qualities of the German positions around the southern half of Metz. It became clear that any gains made along the Moselle near Metz could not be exploited without doing something about the German defensive positions in the forts.

Fort Driant, in particular, with its 150mm guns, could bring down flanking fire and was already producing casualties among XX Corps personnel as Walker’s men tried to throw bridges across the Moselle. Patton decided that while it might not be able to continue an offensive posture, Third Army was not going to remain idle during the lull. Third Army would conduct a reconnaissance in force, and if anything broke open the gains would be exploited.

It became the task of Patton’s XX Corps, and its commander, Maj. Gen. Walker, to take Metz and its fortification system. It was quickly ascertained that the key to Metz was Fort Driant, and on September 17 an excited Walker came up with a plan for its capture, code-named Operation Thunderbolt. This was to be a combined air and ground assault against Fort Driant.

Operation Thunderbolt called for close support from the XIX Tactical Air Command and the use of massed formations of medium bombers. The air attack would then be followed by an intense artillery barrage and a combined assault by armor and infantry. Ground attack aircraft would provide close support as needed. Walker advocated this plan to Patton partially because he did not want Eddy and the XII Corps to get all the glory with their operations outside Nancy. Operation Thunderbolt was conceived when Colonel Charles W. Yuill of the 11th Infantry Regiment in Maj. Gen. S. Leroy Irwin’s 5th Division suggested that Fort Driant could be taken by storm with only a few regiments.

The key to the success of the attack on Fort Driant was to be massed attacks from the air. Patton had high hopes that the bombing would work but probably underestimated the defensive edge afforded by tons of well-placed concrete. Two events that occurred before the attack threw a shadow of doubt upon the success of the operation. The 12th Army Group placed the use of its bombers on a day to day basis and could not commit them long-term to a protracted operation, but far worse, the weather became cold and rainy. Mobility was hampered, and air support would be limited.

Patton later became disappointed with the results obtained from the use of air power. He should have seen this going into the operation because of the ineffective results of massed bombing on the German heavy defenses in Brittany. Operation Thunderbolt was slated for anytime after September 19. The 2nd Battalion, 11th Infantry was kept on alert and told that it might be called upon to go in at a moment’s notice. Because of a lack of ammunition of all types, the concept of a massed attack on the fort was abandoned and air power would be parceled out to different areas of the front on a daily basis.

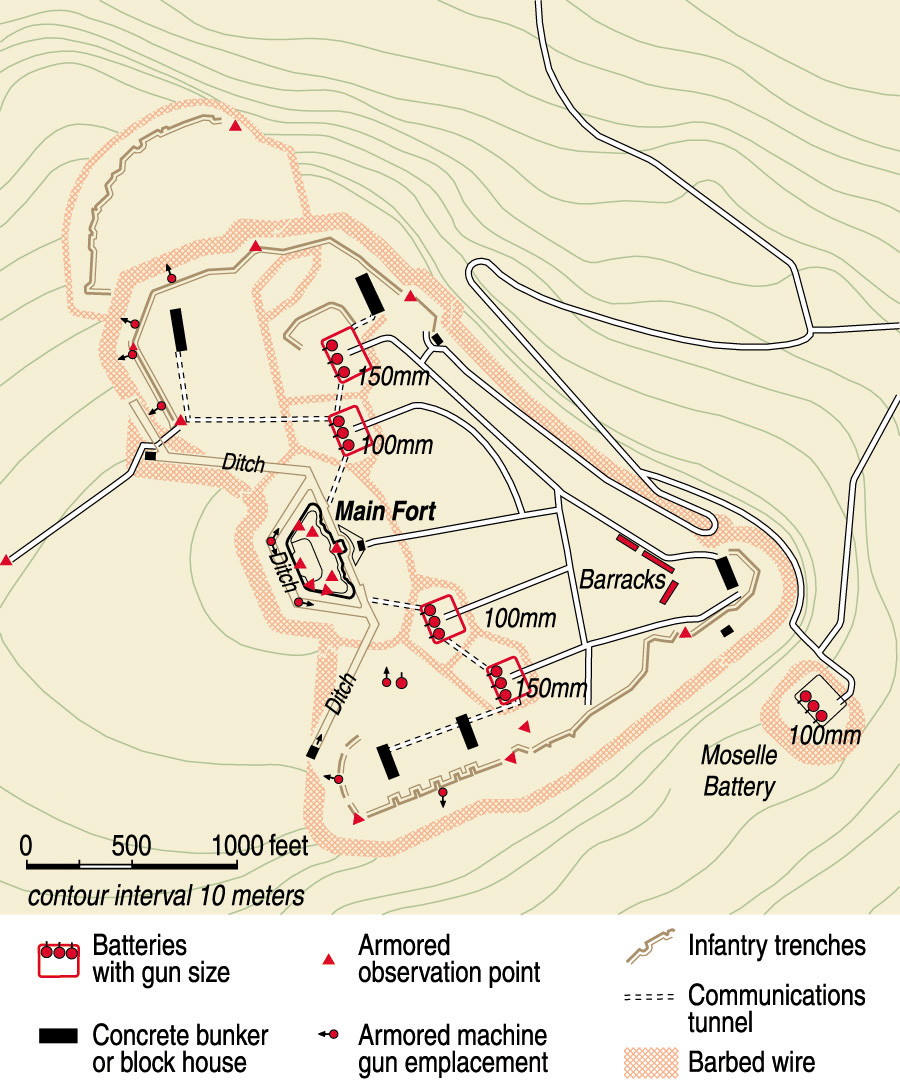

Named after a French officer who had died at Verdun in 1916, Fort Driant sat atop a 360-meter hill, facing southwest. Known originally as Feste Kronprinz, the French changed the name in 1918 to Groupe Fortifie Driant. With a frontage of 1,000 yards, it contained four artillery casemates and five bunkers that could each hold 300 men. The Allies had little more intelligence about the fort other than it covered all the approaches to the Moselle and probably had a small garrison of poorly supplied second-line troops.

Detailed maps and plans of the fort were provided by a French officer who hid them in Nancy during the 1940 German attack. The fort was surrounded by a belt of thick forest, which is where the American attack would begin. The fort itself was 700 yards deep, and each of the casemates contained a three-gun battery of 100mm or 150mm guns. Sprinkled throughout were armored observation posts and pillboxes that were all connected by a maze of underground tunnels. The entire fort was surrounded by a 60-foot dry moat with a further 60 feet covered by an interwoven mass of barbed wire. The Germans made sure that the fort was well supplied with adequate amounts of food, water, and ammunition.

The air attacks against Fort Driant began on September 15 but provided only minimal results. The XIX Tactical Air Command (TAC) scored several direct hits with 1,000-pound bombs against the fort, but inflicted little damage. The Allies brought up several heavy 240mm artillery pieces and fired on Fort Driant, but also produced little damage.

September 27, 1944, was a clear and dry day. At 2:15 pm P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers dropped napalm and high explosives. Some of the fighter-bombers ran the gauntlet of the intense flak curtain thrown up by the Germans and dropped as low as 50 feet to ensure the accuracy of their hits. No appreciable damage was observed, and another wave of fighter-bombers dropped bombs into trenches and on top of the fort. Next, 155mm howitzers opened up on the fort with their massive shells. Explosions were seen directly on pillboxes and the front slope of the fort. It was literally like throwing tennis balls against a wall. None of the artillery or air bombardment had inflicted significant damage.

Next, two companies of infantry from the 11th Regiment and a company of tank destroyers moved out under a smoke screen. The force soon encountered the dry moat and the heavy concentration of barbed wire. The Germans held their fire until the Americans drew close then unleashed a storm of machine-gun fire and mortar rounds. The tank destroyers drove forward and engaged the pillboxes one on one with no effect.

Several platoons of infantry succeeded in getting through the wire and around to the west side of the fort. Here they were met with a barrage of small arms and machine-gun fire causing them to withdraw. Finally realizing that the fort was far more complex and dangerous than previously assumed, General Irwin gave Colonel Yuill permission to withdraw his force at 6:00 pm. The American attack had been stopped cold, and the Allies were forced to rethink how they would take the fort.

Patton, Irwin, and Walker met on September 28, but there was no mention of abandoning the attack—only that a new approach was necessary and the 4th Armored Division needed to rest and regroup. In fact, Walker remembered Patton saying at the time, “We have put our hands to the plow; we must finish the job.” Several of Patton’s aides recommended breaking off the attack and commencing a double envelopment of Metz. The suggestion was overruled by Patton’s desire to continue fighting during the lull and Walker’s determination that the fort would eventually be carried.

The next attack on the fort would feature a larger role for the combat engineers. It was scheduled for October 3, and in that time the army would receive as much training as possible in attacking fortifications. On the morning of October 3, the weather was rainy and miserable. The promised air support did not materialize, and Irwin, not wishing to wait any longer, ordered the attack to commence. The tanks moved forward and attacked the fort with high explosive, concrete-penetrating shells. The engineers went into action with satchel charges, pole charges, and bangalore torpedoes. Specially designated tanks called tank-dozers pushed forward long pipes filled with explosives known as snakes.

The attack began to unravel almost immediately. The snakes broke apart and could not be properly placed. Accurate German artillery and machine-gun fire ripped large holes in the American infantry lines. The engineers got through the entangling barbed wire and tried repeatedly to place their charges but could not blast through the concrete. Roving German patrols that popped out of the fort’s tunnels mowed down many of the engineers.

Company B was able to work its way around the obstructions and create a gap for other troops to pass through. By nightfall, infantry and tank reinforcements began coming through. The attack then quickly developed into a confusing mass of small unit actions with Germans appearing from nowhere and destroying American tanks and infantry with panzerfaust antitank weapons and machine-gun fire. Company B did manage to reach its objective and had a tentative hold on its position in the southwest corner of the fort by 2 pm.

Captain Harry Anderson of Company B assisted his radioman by clearing one of the bunkers with several hand grenades. The two men entered after the explosions and, instead of finding dead Germans, they found that the enemy had escaped down one of the many interconnecting tunnels. Anderson ran back to bring more men forward in order to exploit their gains. Coming upon another bunker, Anderson tossed in more grenades that were followed by explosions. This time six stunned Germans tumbled out the blast door waving small pieces of white cloth in surrender.

The American attacks stalled briefly but were reenergized by an enlisted man. Private First Class Robert W. Holmlund climbed on top of one of the barracks, kicked off one of the ventilator shafts, and then shoved a bangalore torpedo down into the room. The thunderous explosion caused the Germans to evacuate the building quickly. Holmlund said he “could hear ’em swearing and trampling over one another trying to get out. ” Holmlund was killed later that night and received a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross. All through the night, the scattered American forces took more casualties and became more disorganized.

At dawn, Irwin told Yuill to hang on and wait for reinforcements. He then sent in Company K, 2nd Infantry to hold the line and replace the 110 men lost during the first day of the attack. Throughout the day, American soldiers tried in vain to enter the fort but were stopped by machine-gun and sniper fire. Special flamethrower and engineer units were cut down before they could get near the central core of the fort.

It had long become clear to the Americans that the defenders of the fort were not the old men and boys that they had been told manned the defenses. Instead, among the defenders was a unit from a nearby officer candidate school comprised of fanatical Nazis. The rest of the garrison was made up of ex-Navy and Air Force men.

By nightfall on October 4, an attempt was made to reorganize the American troops that were badly scattered throughout the area. Again, teams of German soldiers emerged from the fort to disrupt any units that tried to regroup. Some of the fighting had moved underground, removing the American tanks from the tactical picture.

At dawn on October 5, the German-held forts that surrounded Driant all opened fire on Driant itself, catching many American units on the surface and producing more casualties. Irwin decided to send in more reinforcements. This probably was done on the advice contained in a message from Captain Jack Gerrie of the 11th Regiment. Gerrie stated, “The situation is critical—a couple more barrages and another counterattack and we are sunk. We have no men, our equipment is shot and we just can’t go … enemy has infiltrated and pinned what is here down. We cannot advance … the enemy arty is butchering these tr [sic] until we have nothing left to hold with.”

By the afternoon of the 5th, Companies B and G were reduced to less than 100 men. Irwin decided it was time for decisive action and formed what was called Task Force Warnock. This force was composed of the 10th Infantry Regiment minus Company A. The task force was committed on the night of October 5-6 and relieved the badly mauled troops on top of the fort. Many of the wounded were evacuated since the German fire had decreased in intensity.

By October 6, Patton’s enthusiasm for the operation was beginning to wane. He said, “Things are going very badly at Fort Driant; we may have to abandon the attack since it is not worth the cost. ” Still, he balked at the idea of canceling the attack since he did not want to lose any perceived momentum in the area. The First Battlion of the 10th Infantry was committed at 10 am hours on October 7. One of the rifle companies was able to take four pillboxes but was unable to hold its position. A German counterattack at 4:15 pm cut the men off, and the survivors withdrew. A single platoon made it into an underground tunnel with a long and narrow passage. Engineers were brought forward to blow open a large iron door. Having accomplished this, the exhausted soldiers found that the Germans had piled old machinery and other wreckage in their path.

Orders were sent back to bring up cutting torches, and these were delivered the next morning. Cutting through the debris and pushing it aside, the men moved forward to find yet another door. Hearing the sounds of digging nearby, the Americans feared that the Germans were undermining the tunnel in order to collapse it on them.

A large 60-pound charge was quickly placed at the far end of the tunnel to discourage the German effort. The explosion’s only result was to release deadly fumes into the room and cause the soldiers to scurry for their gas masks.

The men could hear the approaching Germans and could do little more than pile up some sandbags and wait. Sergeant Dale H. Klakamp of the 7th Engineer Battalion, 5th Infantry Division was later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his heroic actions in the tunnel. While his comrades were in a panicked confusion, Klakamp started erecting the sandbags that would save many of his fellow soldiers, lives.

The Germans soon arrived and peppered the men with machine-gun and small arms fire. Engineers on the German side were passed to the front with satchel charges of their own. One of these charges went off near Klakamp’s platoon and produced more American casualties. Many of the Americans in the tunnel were sickened by the fumes or wounded and needed to be evacuated. Once again, the tactical situation had disintegrated into uncoordinated attacks and general confusion.

Corporal C. F. Wilkinson, a messenger for the 284th Field Artillery, having become completely lost in the maze of tunnels, blundered directly into the main German command post. He was able to beat a hasty retreat before the Germans could capture him.

Warnock had planned an additional attack against two of the southern casemates for the next day but canceled it because of the lack of success already experienced. The entire operation gradually settled into a stalemate with the Americans unable to achieve any further gains and the men hanging on desperately to what had been won in the hard fighting. Food, water, and ammunition were running out, and the men holding positions underground were exposed to the dust and fumes of the tunnels.

By October 9, Patton’s attitude about the attack on Fort Driant had changed completely. He said, “The show is going sour. We will have to pull out. ” It had quickly become a no-win situation for the Americans because both daylight and nocturnal assaults had failed. Daytime attacks were vulnerable to the deadly fire that rained down on Fort Driant from the adjacent forts. At night, assaults were quickly broken up and driven into confusion when the German squads emerged from their underground tunnels.

German resistance stiffened even more on October 11, when the defenders began converting knocked-out tanks into makeshift pillboxes. German self-propelled assault guns appeared to lay down harassing fire on the Americans. On the night of October 12-13, the remaining American forces were withdrawn from Fort Driant. The casualties in the operation had been inordinately high and can be blamed on the Americans’ complete lack of training for such operations. The Third Army suffered 64 men killed, 547 wounded, and 187 missing, assumed captured.

The attack on Fort Driant was the only battle ever lost by General George Patton. Questions linger as to why the fort was attacked when the Third Army had little or no gasoline and could have been spending the time resting, regrouping, and preparing for the coming invasion of Germany. The XX Corps had failed to take Fort Driant, but Patton’s XII Corps enjoyed some success south of Metz in its line-correcting operations along the Seille River.

Attacking the fort may have appeared to be a costly blunder, but Patton could not resist the temptation to try out the defenses. If he had done otherwise, he would have surrendered the valuable momentum his army had gained in its drive across France. The cost of the operation must be measured against the gains of keeping the army at a high level of combat readiness and giving the soldiers valuable on-the-job training against fixed fortifications. The cost to the Germans was far higher, with Balck suffering the loss of 43,200 men during the October fighting. Furthermore, the Germans lost valuable tanks and other equipment that could not be easily replaced.

Attacking the fort may have appeared to be a costly blunder, but Patton could not resist the temptation to try out the defenses. If he had done otherwise, he would have surrendered the valuable momentum his army had gained in its drive across France. The cost of the operation must be measured against the gains of keeping the army at a high level of combat readiness and giving the soldiers valuable on-the-job training against fixed fortifications. The cost to the Germans was far higher, with Balck suffering the loss of 43,200 men during the October fighting. Furthermore, the Germans lost valuable tanks and other equipment that could not be easily replaced.

By the end of November, all the forts had capitulated except Fort Driant. It eventually fell on December 8 after the Third Army had completely enveloped Metz. Although the attack on Fort Driant was a tactical loss for Patton, the overall strategic picture favored Third Army.

Compared with the Third Army drive in previous months, Patton advanced only a short distance in the foul weather, crossing swollen rivers. However, he succeeded in his goal of an offensive-defense and inflicted massive casualties on the German Army.

It became evident that Patton’s role in the European Theater of Operations was far from over when on December 16 he received a frantic call from Bradley informing him that the Germans had mounted a major offensive in the Ardennes. This was a role that Patton savored; the Third Army would be the cavalry and come to the aid of the besieged 101st Airborne in the city of Bastogne. Finally, George S. Patton Jr. and his army could move again.

Duane E. Shaffer is a library director and a graduate of Duquesne University. He dedicates this story to the memory of his uncle, Pfc. William Paul Kennedy, who was killed in action outside Les Quatre Fers on October 8, 1944.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments