By Kevin Hymel

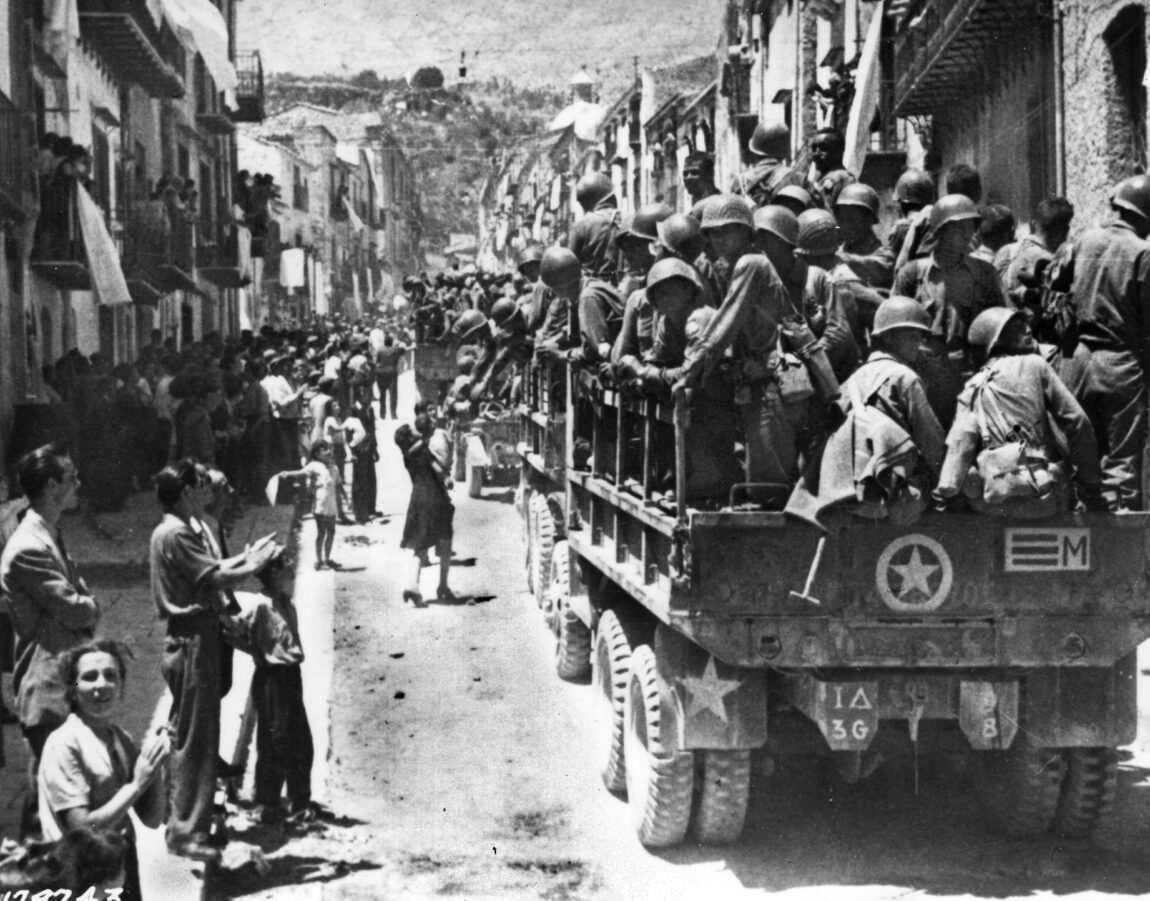

When the Sicilian port city of Palermo fell to Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Seventh Army on July 22, 1943, his soldiers were surprised by their reception. Women dressed in their finest clothes kissed, hugged, and shook the GI’s hands. Jeeps, trucks, and tanks came under showers of flowers, almonds, apples, and lemons. Some people ran forward to offer melons, others offered advice on where mines and booby traps were hidden in Palermo harbor.

The infantrymen of the 3rd Infantry Division, tankers of the 2nd Armored Division, and paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division enjoyed the cheering crowds. In some places policemen had to restrain the enthusiastic populace. Reporter Alexander Clifford remembered being swarmed by happy civilians. “Our hands were wrung until they were limp and sore,” he wrote. “Men and women kissed us—it was noticeable that there was no shortage of garlic.” The locals stuffed the reporter’s pockets with nuts and fruit and offered him a seemingly endless supply of wine. They slapped him on the back and cheered him with what little English they knew: “You are welcome,” or “America, England, Sicily, I come!” Clifford even noticed a few Italian soldiers joining in the merriment.

The surrender was made official when Patton entered the city that night at the head of an armored column. Civilians cheered “Down with Mussolini!” and “Long live America!” They tossed flowers at him. “It is a great thrill to be driving into a captured city in the dark,” he later confessed. Patton’s column rolled to the Royal Palace, where he congratulated his commanders and passed a flask around to celebrate.

Clifford summed up the excitement of the day’s events when he reported, “Hitler and Mussolini should have been here today. They would have learned a lot.”

The father of a good friend was a medic with the 2nd armored division the whole war from North Africa to V.E. day. He saw horrific things and had to perform gruesome duties. He no doubt had battle fatigue or what we now call PTSD. I don’t know what kind of shape he was in immediately after the war, he received at least 1 bronze star and went on to become a doctor. He was the nicest kindest man you could hope to know. We talked a little about the war but not in great detail but it wasn’t till later when I read “An Army at Dawn. ” by Rick Atkinson that I understood more of what George had endured and what a tremendous person he truly was.