By Michael E. Haskew

As French resistance to the Nazis collapsed following the lightning invasion of May 10, 1940, General Charles de Gaulle chose exile in Great Britain, cloaking himself in the mantle of guardian of his nation’s honor. De Gaulle had held but a lowly office in the government of Prime Minister Paul Reynaud. When Reynaud was succeeded by octogenarian Philippe Pétain, a hero of World War I, and his collaborationist Vichy regime, de Gaulle became a wanted man in his own country for refusing to participate in a tragedy of unspeakable shame.

From London, de Gaulle delivered a stirring address to his countrymen on BBC radio, galvanized opposition to the Vichy government and the Nazis in French colonies around the world, and organized the Free French movement. In the process, de Gaulle managed even in defeat and destitution to maintain France’s position among the preeminent nations of the world. Few men in history have displayed such single-minded purpose and succeeded against such long odds.

Michael E. Haskew, editor of WWII History magazine, has researched the life of Charles de Gaulle extensively, and the following is an excerpt from his book De Gaulle: Lessons in Leadership from the Defiant General, recently released by Palgrave Macmillan.

In leaving for London, de Gaulle had crossed his personal Rubicon. With the 84-year-old Pétain in power, he had effectively turned his back on the government of France. By refusing to be a party to an armistice with the Nazis, he had stepped back from much of what he held sacred, including the discharge of his duties as an officer in the French Army. He chose exile and had no legitimate claim to authority or to represent his country. He had come to Britain totally dependent on the goodwill of his hosts and until a few days earlier had been an obscure brigadier general.

Considering his situation, de Gaulle later reflected on his intentions while writing his memoirs. “I was nothing to begin with. But this very destitution pointed out my line of conduct. It was by taking up the cause of national salvation, without troubling about anything else at all, that I might acquire authority. It was by acting as the unbending champion of the nation and the state that it might be possible for me to gather agreement and even enthusiastic support among the French and to obtain respect and esteem from foreigners. In short, although I was so restricted and alone, and indeed because I was so restricted and alone, I had to reach the heights and never come down again.”

After sizing up the situation, de Gaulle was informed that Churchill would meet with him that afternoon. Working under the shade of the trees in the garden at 10 Downing Street, the prime minister greeted the French refugee warmly, and the two men conferred briefly. Each of them wanted to keep France fighting as long as possible, and it was apparent to Churchill that having a Frenchman in London to help cultivate a resistance movement against the Nazis would be a benefit.

The most effective means of reaching and rallying the French people would be by radio broadcast over the BBC, asserted de Gaulle. Churchill agreed, but he had to persuade several members of his war cabinet, who believed that there was no solid ground on which de Gaulle could stand. Britain still maintained relations with the Pétain government, they reasoned, and the more proper course of action might be to see how its negotiations with the Nazis proceeded before allowing de Gaulle access to the BBC.

Churchill disagreed but intended to allow Pétain to add legitimacy to de Gaulle’s intended broadcast by announcing his intent to parlay with the Germans. If Pétain made such an announcement, it would be seen as a breach of the agreement with Great Britain and would further rally those Frenchmen who did not share the old marshal’s defeatist sentiment. Pétain obliged, broadcasting from Bordeaux on the afternoon of June 17. He intoned, “I give to France my person to assuage her misfortune. It is with a broken heart that I tell you today it is necessary to stop the fighting.”

One of de Gaulle’s associates in France had given him the keys to a small apartment in London, and there he began to write the text of his address, which would come the following evening. Courcel had already contacted a longtime friend, Elisabeth de Miribel, who was working at the time in the Economics Mission at the French Embassy, and asked her to come to the apartment to do some typing of a very important nature.

De Gaulle wrote and rewrote the text of his address, which came to be known as the Appeal of June 18. Just before 6 pm, he and Courcel arrived at Broadcasting House, the BBC headquarters. The Frenchmen were greeted by Stephen Tallents, the head of the BBC News.

Elizabeth Barker of the BBC remembered that de Gaulle was “a huge man with highly polished boots, who walked with long strides, talking in a very deep voice … above all, icily contained within himself—not at all what one imagines a Frenchman to be. There was something different about him, different from other men. One could sense that straight away. I don’t mean the ‘man of destiny’ business, but he was most remarkably self-possessed.”

When he reached Studio 4B, on the fourth floor of the building, two announcers, Maurice Thierry and Gibson Parker, were present, and Thierry was reading the news. De Gaulle was asked to give a voice level and said only two words, “La France.” The level was acceptable.

In that clear, resonating voice for which he was known, de Gaulle delivered his first address to the French nation. Its duration was only about four minutes, and it was given during a time slot generally reserved for a news broadcast to France. The BBC personnel had been given scarcely an hour’s notice that de Gaulle was coming, and no arrangements for a recording were made. Few people were reported to have actually heard the appeal as it was broadcast; however, it was reproduced in print.

De Gaulle stared at the microphone and began: “The leaders who have been at the head of the French armies for many years have formed a government.

“This government, on the pretext that our armies have been defeated, have made contact with the enemy in order to cease the fight.

“Certainly we have been, we are, overwhelmed by the enemy’s mechanical strength on land and in the air.

“Far more than the numbers of Germans, it is their tanks, their planes, and their tactics which have taken our leaders by surprise and brought them to where they are today.

“But has the last word been said? Must hope be abandoned? Is our defeat complete? No!

“Believe me when I tell you that nothing is lost for France. I speak in knowledge of the facts. The same means which have defeated us can bring us victory one day.

“For France is not alone! She is not alone! She is not alone! She has a great empire behind her. She can unite with the British Empire which rules the seas and is continuing the fight. Like Britain, she can make unlimited use of the immense industrial resources of the United States.

“This war is not restricted to the territory of our unhappy country. This war has not been decided by the Battle of France. This war is a world war. All our errors, all our delays, all our sufferings do not alter the fact that the world contains all the resources needed to overwhelm our enemies one day. Struck down today by mechanized might, we can conquer one day in the future by superior mechanized might. The fate of the world turns on that.

“I, General de Gaulle, now in London, call on all French officers and soldiers now present on British territory or who may be so in the future, with or without their arms; I call on engineers and specialist workers in the arms industry now present on British territory or who may be so in the future, to get in touch with me.

“Whatever happens, the flame of French resistance must not and will not be extinguished.

“Tomorrow, as today, I shall speak on the radio from London.”

This four-minute appeal, heard by few, and delivered without fanfare, was by no means the commencement of a Free French movement. There was the ring of defiant nationalism, however, and in it the last vestige of any willingness to serve a collaborationist government. The Vichy leaders, preparing to sign an armistice with the Nazis, had ordered their armed forces to cease resistance. An obstinate junior officer had refused these orders, fled to the protection of another country, and was urging others to do the same. Each, in the eyes of the other, had committed high treason.

For the British, June 18 did not present a moment of realization that Charles de Gaulle was the last or even the best hope for rallying the French nation to continue the fight. Actually, Monnet had persuaded Churchill to organize yet another mission to France to seek the support of any senior French soldier or diplomat who might be willing to return to Britain and lead the nation. Among them were Reynaud, Weygand, Lebrun, and former prime minister Leon Blum. There were numerous men with political standing who might have stepped forward to accept the challenge. For various reasons, none did.

The spacious flying boat, with room for more than 30 passengers, which Churchill had provided to fly French leaders to Britain departed virtually empty. Some Frenchmen had invoked the flimsy prospect that a resistance government might still take root in North Africa. Indeed, on Friday, June 21, the liner Massilia was released by Admiral of the Fleet and de facto commander of the entire French Navy, François Darlan, and set sail for Casablanca. Chief among the passengers was former prime minister Daladier, and those aboard may well have believed that they were headed to North Africa to continue the fight.

Meanwhile, the drama of capitulation played out in the forest of Compiegne. Hitler and the Nazis had seen fit to exact their retribution for the armistice of November 1918, which had ended World War I, with a spectacle to humiliate the representatives of Pétain and the entire French nation. The old railroad car in which the Germans had signed the earlier armistice was brought from a museum in Paris, and the French delegation was led to it in the same place where the signing had occurred nearly a quarter century earlier.

Hitler denied Mussolini’s request that Italy be awarded territory including the port cities of Toulon and Marseilles, the valley of the River Rhone, and dominion over Corsica, Tunisia, and Djibouti, a city in the horn of Africa that was adjacent to Italian-held Ethiopia. Instead, the Führer had opted to present the French with 23 conditions for the end of hostilities, none of which, he hoped, would induce them to continue armed resistance.

Intending to separate France from Britain, Hitler sought to “secure, if possible, a French government functioning on French territory. This would be far preferable to a situation in which the French might reject the German proposals and flee abroad to London to continue the war from there.”

While the British had been rightly concerned with the disposition of the French Fleet, and Churchill had been repeatedly assured that it would not be surrendered to the Germans, Hitler had conversely determined that the fleet should not fall into British hands. In order to assuage any French concern on this point, he offered a dubious assurance to the delegation in the surrender terms. “The German government solemnly declares to the French government that it does not intend to use for its own purposes in the war the French fleet which is in ports under German supervision…. Furthermore, they solemnly and expressly declare that they have no intention of raising any claim to the French fleet at the time of conclusion of peace.”

At 7 pm on June 22, General Huntziger signed the armistice agreement on behalf of the Pétain government. When they heard that the armistice had been concluded, those French officials aboard the Massilia en route to Casablanca attempted to persuade the captain of the vessel to change course and sail for Britain. However, the request was refused. When the ship arrived in North Africa, its passengers were placed under arrest and confined to the ship in the harbor.

In London, a politically astute de Gaulle moved to establish himself as either the legitimate leader of the French resistance or as a willing subordinate to the authority of a more senior officer or diplomat. Debate continues as to his actual motivation. Regardless, he did send a telegram to the headquarters of General Auguste Nogues, in Rabat, Morocco, on June 19 stating, “Hold myself at your disposal, whether to fight under your orders or for any step which might seem to you useful.”

Nogues, the commander of French forces in North Africa, had expressed a sentiment to resist the Nazis but abruptly changed course when the armistice was signed, as evidenced by his request for instructions on dealing with the diplomats aboard the Massilia. Curiously, he maintained a degree of independence under the Vichy government and kept his Moroccan troops, the fierce Goums, armed and under his personal control. Eventually, these troops were released to Allied command and fought with distinction in Italy. On this occasion, however, de Gaulle received no reply of substance.

Further, on June 20 de Gaulle appears to have parted with his standard course of action and swallowed his pride in a personal letter written to Weygand, whom he detested. “I feel that it is my duty to tell you quite simply that I do wish for the sake of France and for yours that you may be willing to remove yourself from disaster, reach colonial France and continue the war. At this time, there is no possible armistice with honor. I could be of use to you or to any other prominent Frenchman who is willing to place himself in command of a continued French resistance movement.”

The letter, which was sent to Weygand through the French military attaché in London, was returned to de Gaulle three months after it was written. Along with it was a note that advised the sender to communicate with Weygand through appropriate government or military channels.

With the outward appearance of a willingness to be led, Charles de Gaulle had invited another individual, someone better known and possibly better received by the governments of Great Britain and the United States, and more important, someone to whom the armed forces of the far-flung empire would rally, to come forward and assume the role of leader of the resistance. One tantalizing question lingers. How would he have reacted if a notable Frenchman had done just that?

As it was, shock and paralysis gripped the diplomatic and military leadership of France. As Pétain capitulated and the Vichy regime was born, not a single person came forward to contest de Gaulle for the role he had always believed himself destined to play.

As he had promised, he took to the BBC microphone again on Wednesday, June 19. This time, his tone was much more emphatic. “Faced by the bewilderment of my countrymen,” he said, “by the disintegration of a government in thrall to the enemy, by the fact that the institutions of my country are incapable, at the moment, of functioning, I, General de Gaulle, a French soldier and military leader, realize that I now speak for France.

“In the name of France, I make the following solemn declaration: It is the bounden duty of all Frenchmen who still bear arms to continue the struggle. For them to lay down their arms, to evacuate any position of military importance, or to agree to hand over any part of French territory, however small, would be a crime against our country…. Soldiers of France, wherever you may be, arise!”

This second appeal was delivered while Monnet was in Bordeaux on his last-ditch British-sponsored mission to find a prominent Frenchman to come to London. Apparently, de Gaulle was also keenly aware of his opportunity to move while Monnet was absent. Although the two had been cordial, they disagreed on the method and the means by which to shape a cohesive French resistance to the Nazis.

Monnet saw events as moving too rapidly and was concerned that de Gaulle’s declaration that he represented the country might alienate the leadership of the French empire across the globe. Such a situation would only make matters of resistance more difficult. He also believed that any resistance movement organized and centered in London would look to all the world as a puppet of the British government.

For de Gaulle, the moment to act was at hand. His intense nationalism trumped the perceived need for consensus among Frenchmen outside the immediate reach of the Pétain government. Monnet later chose not to join de Gaulle and the Free French, but accepted an appointment by the British government to work with its purchasing mission in Washington, D.C.

When news of the armistice reached London, there was undoubtedly a final acknowledgment that a resistance movement was the best hope for Frenchmen to continue fighting. On June 23, the British government issued two landmark statements. The first condemned the separate peace, and the second, without specifically naming de Gaulle, expressed its intent to work with French leaders in exile.

“The Armistice which has just been signed, in violation of the agreement solemnly concluded between the allied governments, places the Bordeaux government in a state of total subjection to the enemy, depriving it of all freedom and of any right to represent free French citizens. Consequently, His Majesty’s government no longer considers the government of Bordeaux as that of an independent country,” read the initial communiqué. This was followed by the announcement that Britain had become aware of a “plan for the formation of a provisional French National Committee” that would represent those “independent French elements resolved to fulfill the international obligations contracted by France” and that it “would recognize … [and] discuss with it all matters connected with the prosecution of the war.”

Of course, the head of this French National Committee was to be Charles de Gaulle, who was given as office space the third floor of the St. Stephen’s House along the bank of the river Thames and near the House of Commons. There was to be an oath—to serve this newly and largely self-appointed leader with honor, fidelity, and discipline. A number of French government officials shied away, including Corbin, who chose retirement in South America rather than partnership with the Free French, as the committee soon came to be known. Those who chose early to enlist with de Gaulle occupied offices near their leader, on the third floor of a somewhat dingy building in a foreign country.

By June 26, any ambiguity as to the British position with regard to the Free French and its de facto leader was erased. A British diplomatic mission to Morocco had been rebuffed, and Churchill called de Gaulle to his quarters at 10 Downing Street. “You are all alone,” said the prime minister. “Well then, I recognize you all alone.” This was followed by a declaration that “recognizes General de Gaulle as leader of all the Free French, wherever they may be, who join him in the defense of the Allied cause.” Although this aroused some protest within the government, it was at long last done. In an evening radio address, de Gaulle stated boldly, “I take under my authority all the French who are now living in British territory or who may arrive later.”

Setting about the business of government—or something similar to government—posed great challenges for the fledgling Free French. The 100,000 francs contributed by Reynaud were exchanged for only 100 pounds sterling, a paltry treasury at best. Diplomatic relations with the British were entrusted to Gaston Palewski, who had been personally summoned to London from Tunisia. As for the military, remnants of French Army units were scattered in London and southern England, some of which had been ferried to safety from the debacle at Dunkirk.

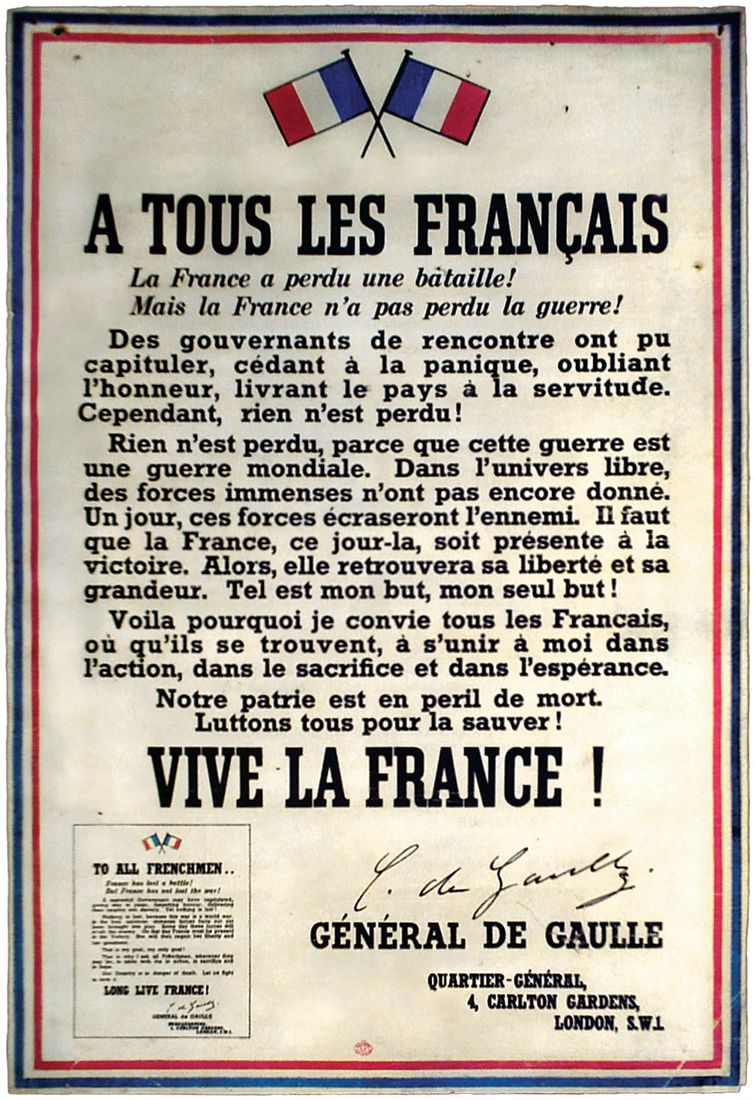

Altogether, about 20,000 French soldiers were in Britain, including the 13th Demi-brigade of the Foreign Legion, a light division of mountain troops, a few dozen pilots, and an odd collection of volunteers. Only a trickle of men came to the Free French recruiting station at Olympia Hall. A poster bearing the French Tricolor was printed, and the message was from the leader in exile. “To all Frenchmen,” it read. “France has lost a battle, but France has not lost the war. Some chance-gathered authorities, giving way to panic and forgetting honor, may have surrendered, delivering the country over into bondage. Yet nothing is lost! That is why I call upon all Frenchmen, wherever they may be, to join me in action, in sacrifice and in hope.”

Soon, the Free French adopted the Cross of Lorraine as their symbol. It was a reminder of the province of Lorraine, which had long been disputed territory and was now again under the control of the Germans. Perhaps even more powerfully, it reminded the French people of the emblem under which Saint Joan of Arc had fought an occupying enemy centuries earlier.

A division, which had been involved in an unsuccessful campaign in Norway, arrived as well. Its commander, General Émile Béthouart, was for a time the senior French Army officer in Britain. He declined to join de Gaulle or to subordinate himself to his junior. Instead, he eventually made his way to North Africa and fought on, serving capably. Before he departed, Béthouart arranged for de Gaulle to address several units and enlist their support for the Free French cause. Following one address, de Gaulle was reportedly successful in persuading 1,000 men to join him. Nevertheless, the recruiting process was painfully slow.

One of Béthouart’s junior officers, Captain André Dewavrin, sought the Free French headquarters on his own and finally reached St. Stephen’s House after a confusing journey that had been all the more complicated because road signs had been removed or camouflaged. Courcel received the young officer and presented him to de Gaulle.

Years later, Dewavrin remembered the meeting: “I walked into a spacious well-lit room. Two large windows opened onto the Thames. The huge form unwound and stood up to greet me. [The General] made me repeat my name and then asked me a series of short questions in a clear, incisive, rather harsh tone:

‘Are you on the active list or the reserve?’

‘Active, sir.’

‘Passed staff college?’

‘No.’

“Where were you?”

‘The École Polytechnique.’

‘What were you doing before the mobilization?’

‘Professor of Fortification at the École Spéciale Militaire de Saint Cyr.’

‘Have you any other qualifications? Do you speak English?’

‘I have a degree in law and I speak English fluently, sir.’

‘Where were you during the war?’

‘With the expeditionary corps in Norway.’

‘Then you know Tissier [newly appointed chief of staff]. Are you senior to him?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Very well. You will be the head of the second and third bureau on my staff. Good day. I shall see you again soon.’

The conversation was over. I saluted and went out. The reception had been glacial.”

The Vichy government did not sit idly by while the spectacular Free French affront developed. By the end of the month, de Gaulle’s temporary rank of general had been rescinded, he had been forced into retirement and summarily stripped of his French citizenship, and a message delivered through the French embassy in London ordered him to report to prison in Toulouse within five days in preparation for trial on charges of disobedience. This tribunal found him guilty, sentenced him to four years in prison, and levied a fine of 100 francs.

In a second trial held in early July, he was found guilty of desertion and undertaking to serve a foreign country. This tribunal voted five to two to convict and sentenced him to death in absentia. Although Pétain voiced his agreement with this verdict and the sentence, he was reported by some to have vowed that the death sentence would never be carried out.

De Gaulle responded to the events at Vichy with disdain, saying that he considered its actions null and void and that he would have a discussion after the war with those who pronounced his guilt and his sentence. Only de Gaulle could actually grasp the potential personal consequences of the path he had chosen; however, it was not time to count the cost. There was a swirl of activity and business at hand.

Meanwhile, Yvonne had reached London and eventually decided to relocate to an unpretentious home outside the city. Charles would commute via Victoria Station on those occasions when he was able to see his family.

Even as efforts to establish the Free French organization were bearing some fruit, events occurred that nearly stopped the progress in its tracks. The Vichy government had already reneged on its pledge to transfer captured German airmen to British custody in order to prevent their taking part in the coming Battle of Britain, and indeed these pilots and crewmen were active once again with the Luftwaffe. The disposition of the French Fleet remained an open question, and Darlan, commander of the Vichy armed forces, was not to be trusted.

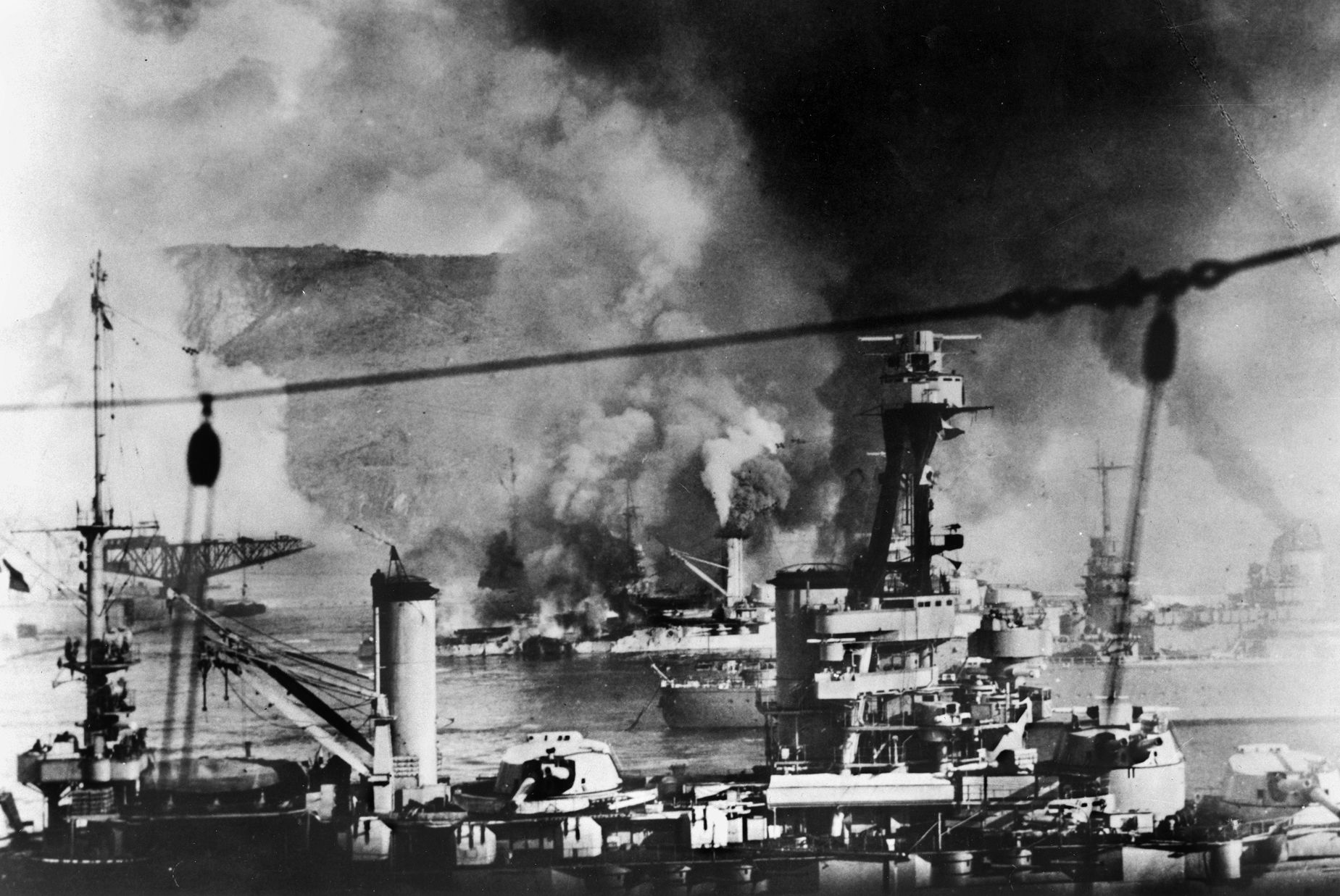

Churchill decided to take action to maintain the preeminence of the Royal Navy, particularly in the Mediterranean. Elements of the French Fleet were already in the British ports of Plymouth and Portsmouth, and these were seized on the morning of July 3, with Royal Navy and Marine boarding parties taking control and marching the French crews to internment. Four British participants were wounded, and a French sailor was killed. A total of 130 French vessels were taken under British control.

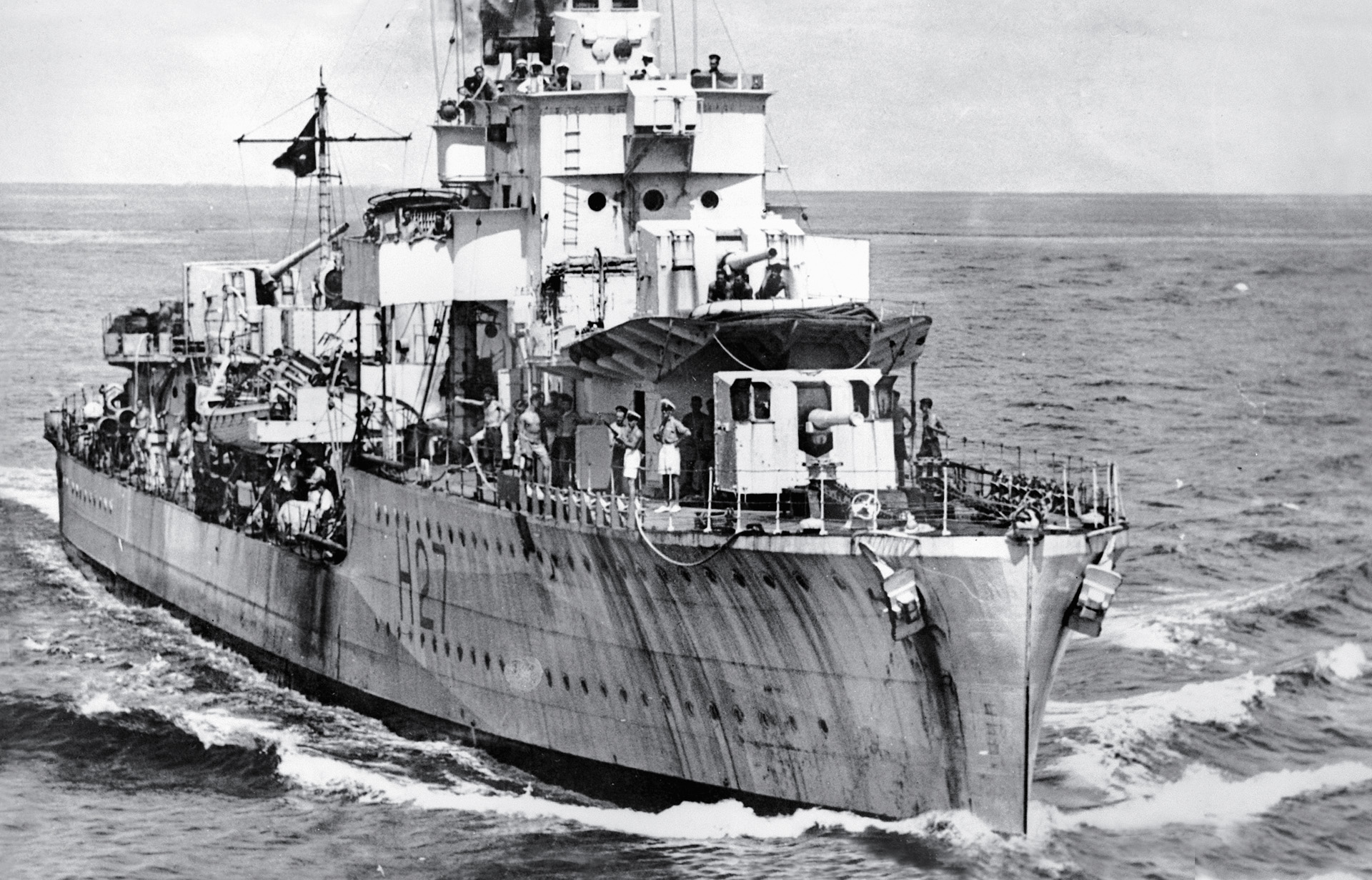

Other French warships were under either German or Vichy control at Cherbourg, Toulon, and Brest, or scattered in North African ports. The most substantial concentration of French naval assets was located at the port of Mers el-Kébir, in Algeria. These included the battleships Strasbourg, Dunkerque, Bretagne, and Provence, six destroyers, and a complement of support vessels and submarines.

Churchill ordered Admiral Sir James Somerville to sail from Gibraltar with an ultimatum for the French commander, Admiral Marcel Gensoul. The French could sail with the Royal Navy warships and continue to resist the Germans; sail to British ports with reduced crews, tender their ships, and be repatriated to France; or sail to the island of Martinique in the West Indies, where they would be disarmed and out of the reach of the Germans.

Somerville, whose Force H consisted of the battleships Valiant and Resolution, the battlecruiser Hood, the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, and several cruisers and destroyers, reached the French anchorage on July 3 with firm instructions from Churchill to conclude the difficult task by the end of the day. A British destroyer entered the harbor and delivered the message to Gensoul. Its conclusion was ominous should the French choose not to comply with one of the three options offered: “We must with profound regret require you to sink your ships within six hours or it is the orders of His Majesty’s government to use whatever force may be necessary to prevent your ships from falling into German or Italian hands.”

Gensoul, who took his orders from Darlan, rejected the ultimatum, and just before 6 pm the British opened fire on the anchored French ships. Only the Strasbourg and an escorting destroyer managed to raise steam and escape from the carnage. Nearly 1,300 French sailors were killed and more than 350 wounded. It was a moment of supreme and tragic irony, in which the defenders of freedom had come to blows and the oppressors would find fodder for their propaganda machine.

Churchill regretted the decision to fire on the French but considered it a necessity. He later wrote, “Here was Britain, who so many had considered down and out, which strangers had supposed to be quivering on the brink of surrender to the mighty power arrayed against her, striking ruthlessly at her dearest friends of yesterday and securing for a while to herself the undisputed command of the sea. It was made plain that the British War Cabinet feared nothing and would stop at nothing.”

De Gaulle received word of the Mers el-Kébir tragedy on the evening of June 3 and erupted in both anger and anguish. As the leader of the Free French movement, supported by Great Britain, he appeared at worst to have potentially been a party to the terrible event. At best, it was those on whom he depended who had placed his entire effort in jeopardy. Recruiting to the cause would only be more difficult, and even more troublesome, he would be required to speak to the situation on the BBC. Prolonged silence would be unacceptable. He would gather himself and do what was necessary.

Churchill, at times a harsh political realist, understood the precarious position in which the action at Mers el-Kébir had placed de Gaulle and invited the Frenchman to lunch at 10 Downing Street. Together with Mrs. Churchill he conversed with de Gaulle, and inevitably the discussion turned to the unfortunate situation. Fluent in French, Mrs. Churchill expressed a hope that the navies of the two countries might yet work together. De Gaulle responded that the French Fleet might gain its greatest satisfaction by actually turning its guns on the British.

When Mrs. Churchill replied in perfect French that the remark was unbecoming for an ally or guest of Great Britain, the prime minister intervened and attempted to settle the conversation down. However, Mrs. Churchill persisted and stated, “No Winston, it is because there are certain things that a woman can say to a man which a man cannot say, and I am saying them to you, General de Gaulle.”

Taken aback, de Gaulle, for one of the few times in his life, apologized to Mrs. Churchill and sent a large basket of flowers to her the following day. The general and the lady remained friendly from that time on, and it was said that she was an advocate for him with her husband whenever possible.

On July 8, a resolute de Gaulle took to the radio once again. His higher calling had not diminished the sorrow and frustration of Mers el-Kébir, but somehow he knew that it was bound to happen. Perhaps on that evening he displayed his finest diplomatic ability of the entire war. “Though seeing this tragedy as what it is, I mean as lamentable and hateful, Frenchmen worthy of the name cannot be unaware that the defeat of England would confirm their bondage forever. Our two ancient nations, our two great nations remain bound to one another. They will either go down both together or both together they will win.”

As horrific as Mers el-Kébir had been, it served to strengthen the bond between the Free French movement and Great Britain, and certainly the personal ties between Churchill and de Gaulle. Despite the fact that the Vichy government would use Mers el-Kébir as a propaganda weapon, it also severed political ties with Great Britain, a development that further legitimized and strengthened de Gaulle’s authority. He had contemplated giving up and relocating to a quiet life in Canada, but only momentarily. Capable of comprehending the noble purpose that lay ahead, de Gaulle chose leadership and vision rather than a base, reactionary response. Therein lay the foundation of greatness.

Within weeks of the appointment of Free French staff officials, agents were secretly sent to France to contact those pledged to resist the occupiers from within. A coordinated resistance, embryonic though it was, began to take shape. On Bastille Day, July 14, 1940, the Free French, such as they were, gathered in Grosvenor Gardens. There were actually more British than French in attendance, but all joined in a rendition of “La Marseillaise,” the French national anthem. The moment bolstered de Gaulle’s confidence that he had won the admiration of the British people. To many of them, he stood out as the only Frenchman willing to continue an armed resistance against the Nazis, the only man who would work to restore his country’s honor, and the only man who understood the solemn pledge his nation had made to fight side by side with Britain to the end.

While the Vichy government might posture and pronounce, its reach would prove limited. Its soon to be vilified collaborationist prime minister Pierre Laval might push for even greater cooperation with the Nazis, but with each passing day the prospect of a quick British surrender became less likely. It was to vanish altogether with the Battle of Britain. Further, the will to resist was revived in the French empire. The distant New Hebrides had declared an allegiance to the Free French by the end of June. The governor of Chad, Félix Éboué, pledged his support as well. There were also stirrings in the French Congo. Emissaries were dispatched to secure these colonies.

By August, the Free French and the British government had concluded an agreement for continuing cooperation, including the financing of the Free French movement with the equivalent of $40 million from the British treasury.

De Gaulle had also sought guarantees from the British for the restoration of France and its empire, control over the Free French armed forces that he was actively recruiting, and an understanding that French soldiers fighting under the command of British officers would not be required to fight other Frenchmen. Churchill was in no position to fully guarantee these points. After all, the outcome of the war was far from certain. Britain’s own colonial empire was at risk, and a guarantee of French colonial possessions was quite a stretch. As for Frenchmen fighting Frenchmen, the question would sort itself out should Free French soldiers confront those of Vichy on the battlefield.

While he did not achieve the full measure of his requests, de Gaulle had successfully solidified his hold on the leadership of Frenchmen in exile. The British would deal with him. He would shape the future course of French resistance.

With the heroic defense of the skies over Britain ongoing, Churchill was on the offensive. Hitting the Germans by some means was attractive, and involving the forces of the Free French might enhance the movement’s prestige around the world. At the western tip of the continent of Africa was the port city of Dakar, which had been a French possession since 1857. Although strong-willed pro-Vichy governor Pierre Boisson was in firm control, a joint military operation involving British and Free French troops might succeed in capturing the port, hopefully without bloodshed, and could bring all of French West Africa into the Allied sphere. From the beginning, de Gaulle had misgivings about such an operation, acknowledging that Dakar might be strongly defended. However, he decided to move forward believing that if he did not act the British might do so on their own in the future to prevent Dakar from becoming a haven for German U-boats operating in the Atlantic.

In late September, a naval task force arrived off Dakar with de Gaulle himself aboard one of the ships and 2,500 Free French troops and two battalions of Royal Marines poised to land. Boisson, however, was resolute. Appeals for peaceful cooperation were flatly rejected, and Free French sympathizers in Dakar had already been rounded up and jailed. Under a flag of truce, de Gaulle approached the shore only to be informed that an order for his arrest had been issued. An argument ensued, and it became apparent that no progress would be made. As the Free French delegation backed out of the harbor, machine guns opened fire and injured at least one person.

Fog hampered the operations of Royal Navy warships, which exchanged gunfire with the French battleship Richelieu moored in the harbor. An attempted landing was aborted when the escorting Free French warship was hit by fire from shore batteries. To make matters worse, a Vichy submarine slipped from the harbor and slammed a torpedo into the British battleship Resolution. At last, the invasion force was compelled to withdraw to Freetown in the British colony of Sierra Leone. The entire adventure had ended in failure and colossal embarrassment for Churchill. Most of the blame, though, fell unjustly on the shoulders of de Gaulle.

Although postwar German naval records confirmed that neither Vichy nor German authorities had been aware of the Dakar operation ahead of time, rumors of security breaches among the Free French were rampant. It followed that de Gaulle and company might not be trustworthy or even capable of cooperating in any future military endeavor. Doubtless, Dakar was the low point of the Free French movement.

Churchill defended de Gaulle to the best of his ability and told the House of Commons that mistakes had been made at Dakar. De Gaulle, despondent over the failure, contemplated suicide. Nevertheless, the Allied reception elsewhere in equatorial Africa was more enthusiastic. During the coming weeks, de Gaulle traveled through the French colonial possessions in the region. Aware that the British and Vichy governments were in contact with one another through diplomatic channels, this was a bold step that reached beyond the scope of de Gaulle’s understanding with the British government. It also rattled the British Foreign Office, which had hoped to keep Vichy from completely changing sides and entering the war as an Axis minion.

Continuing his efforts to rally support for the Free French movement among France’s colonies, de Gaulle imperiled his tenuous relationship with the British government. He asserted control that had been granted by no real authority. De Gaulle was filling a power vacuum with decisive, rapid, and independent action.

On October 27, 1940, at Brazzaville, in the French Congo, de Gaulle issued a declaration announcing the formation of a Defense Council of the Empire, which was tantamount to the establishment of a dictatorial government of French possessions, and asserted, “Decisions will be taken by the leader of the Free French, after consultation, if the need arises, with the Defense Council.” A few days later, a second communiqué declared that the government of Pétain was unlawful. De Gaulle had not consulted with the British prior to issuing the declaration, and to compound the difficulty he contacted the U.S. consulate at Leopoldville in the Belgian Congo, hoping to open a discussion of the administration of French colonies in the Western Hemisphere.

While it was true that more and more of colonial France and well-known officers in the French military were rallying to the Free French, it was also apparent that de Gaulle was quickly tiring of simply being the head of a national committee backed by the British. His was to be a government with full diplomatic standing and recognition among nations. For their part, the Americans were not at war in the autumn of 1940 and had little interest in de Gaulle or the Free French. In their estimation, the Vichy government was the government of France. Dakar had done nothing to change their opinion, and now the upstart de Gaulle had the audacity to communicate as a head of state. There is no record of a reply from the U.S. State Department.

De Gaulle returned to London on November 12, following a rather curt communication from Churchill, which read in part, “I feel most anxious for consultation with you. Situation between France and Britain has changed remarkably since you left…. We have hopes of Weygand in Africa and no one must underrate advantage that would follow if he were to be rallied. We are trying to arrive at some modus vivendi with Vichy which would minimize the risk of incidents and will enable some favorable forces in France to develop…. You will see how important it is that you should be here.”

Since the debacle of Dakar in September, Charles de Gaulle had no doubt been keenly aware of the danger that existed. For as much as the Free French might need the British, an overture from Vichy or the rise to greater prominence of someone of stature, such as Weygand, who had in fact been sent by Pétain to assume the post of Delegate General of the French North African colonies, could prove his undoing.

Therefore, his action at Brazzaville is understandable. The growth of the Free France movement with the pledge of allegiance from possessions in the Pacific, the Indian subcontinent, and equatorial Africa would make any deal that excluded de Gaulle from a prominent place at the table more difficult. De Gaulle also realized that he needed the British but remained wary of both Churchill’s government and the Americans throughout the war years and beyond.

In the mid-1950s, he wrote in his memoirs, “To start with … I was nothing. Not the semblance of a force or an organization was behind me…. But my very poverty showed me the line to take…. Only if I acted as the inflexible champion of the nation and the state could I win support among the French and respect from foreigners. The critics who persisted in frowning on my intransigence refused to see that I was controlling countless conflicting pressures and that the least yielding would have led to total collapse. Precisely because I was alone and without power I had to climb the peaks and never afterwards descend from that level.”

Constantly intending to prove that he was no puppet of the British, de Gaulle clashed with his hosts over military and diplomatic issues in the Middle East, quelled dissent against his course of action and rivalry among the members of his own national committee, and managed to stir the anger of even his closest friends in the British government. During one sharp exchange with his liaison officer, General Spears, he spewed venom. “I do not believe that I will ever get along with the English. You are all the same, absorbed in your own interests and business, and very insensitive to the requirements of others. You believe that I am interested in England winning the war? I am not! I am only interested in the victory of France.”

From 1941 on, the relationship between the Free French and the British and American

governments was one of wary suspicion. The strained relationship was heightened

when America entered the war in December of that year.

During the summer of 1941, British and Free French troops fought side by side in a successful campaign to secure Syria and Lebanon from pro-Axis regimes and potential occupation by the Germans. Meanwhile, however, terms were concluded with the Vichy forces in the Levant by British military commanders who did not fully appreciate the delicate nature of Anglo-Free French relations. The interests of the Free French were virtually dismissed. An amended agreement was signed and a crisis averted. Again, the hand of de Gaulle had been inflexible, and his policy of intransigence had paid a dividend.

There were other rifts between Churchill and de Gaulle, not the least of which had to do with an interview the Free French leader granted to George Weller, a reporter for the Chicago Daily News. In the published article, de Gaulle criticized the British.

“England is afraid of the French fleet,” Weller quoted.

“What in effect England is carrying on is a wartime deal with Hitler in which Vichy serves as a go-between. Vichy serves Hitler in keeping the French people in subjection and selling the French empire piecemeal to Germany. But do not forget that Vichy also serves England by keeping the French fleet from Hitler’s hands. Britain is exploiting Vichy the same way as Germany, the only difference is in purpose. What happens is in effect an exchange of advantages between hostile powers which keeps the Vichy government alive as long as both Britain and Germany are agreed that it should exist.”

Churchill fumed and refused to see de Gaulle until he had sufficiently cooled off. During a subsequent meeting, the prime minister warned the Frenchman that he should be careful in cultivating concerns that he was anti-British. Such was the nature of the tempestuous relationship.

Three weeks after Pearl Harbor, de Gaulle also wrangled with the U.S. government over the tiny islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon, off the coast of Newfoundland. Concerns had arisen as to the possibility of weather equipment transmitting information that might be useful to the Germans. While the islands were French possessions, the United States objected to Free French forces from Halifax, Nova Scotia, occupying them. Instead, the Americans had agreed to a Canadian operation. When de Gaulle was informed, he ordered his small force to the islands ahead of the Canadians. The hostile U.S. response was soothed by Churchill, who worked out a compromise allowing the parties at odds to save face. Still, de Gaulle had done little to endear himself to the Americans.

Since their early communications with the British government and their ongoing effort to support Weygand in North Africa were seen as the best hope to keep Vichy out of the war, the American government was reluctant to vest de Gaulle with any specific endorsement of substance. In the autumn of 1941, Free French representative René Pleven had traveled to Washington, D.C., and requested a meeting with Roosevelt or Secretary of State Cordell Hull. Neither would receive him. The reception from Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles was icy.

After U.S. entry into the war, the Roosevelt administration assumed a somewhat more pragmatic approach to de Gaulle and on July 9, 1942, issued a statement that affirmed the contribution of the Free French movement to the war effort and pledged military and humanitarian aid. The United States maintained the stance that the French people should be allowed to freely elect their governing officials after the war. Whether de Gaulle would play a role in the postwar government was for the French voter to decide.

As the war continued, Free French forces fought with distinction in the desert at Bir Hacheim and elsewhere, participated in the abortive Commando raid on the French port city of Dieppe, and supported covert resistance operations inside the Vichy-controlled region of France, which the Germans occupied on November 11, 1942, following the Allied landings on the coast of North Africa three days earlier.

Operation Torch, as the landings were code-named, involved the first offensive action of American troops on the ground during the war against Nazi Germany. U.S. and British landings were to occur on the North African coast at the major cities of Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers. It was hoped that the Vichy forces in control in these areas would quickly surrender and potentially rally to the Allied cause. The long-term goal was to crush German forces under Field Marshal Erwin Rommel between the British Eighth Army, which was advancing westward from the Egyptian frontier under General Bernard Law Montgomery following its victory at El Alamein, and the Americans in the west.

Although the Americans had initially pushed for an assault on the European continent, British military planners prevailed, and it was decided in July 1942 that French North Africa would be the location of the Allied offensive. However, there can be no doubt that Churchill otherwise accepted that the center of Allied power had shifted from London to Washington, D.C., when the United States entered the war. The continuing mistrust of de Gaulle by the Roosevelt administration contributed mightily to a concerted effort to marginalize Free France, or Fighting France, as the movement had been renamed in June.

Hitler had launched his invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, and during subsequent discussions with Soviet officials de Gaulle had promised to urge the opening of a second front in Europe as soon as possible. However, when Roosevelt and Churchill made their decision for North Africa, they also concluded that the Free French were not to be consulted, their aid would not be solicited, and above all, de Gaulle was to know nothing of Operation Torch.

By the summer of 1942, relations between Churchill and de Gaulle reached another low point. British troops had landed on the island of Madagascar, off the coast of East Africa, two months earlier, and de Gaulle had not been made aware of the operation even though he had proposed a joint effort to capture the island as early as December 1941. Perhaps the most adversarial meeting of their careers occurred at 10 Downing Street in September, and both men were smarting from its bitter conclusion, with Churchill even threatening to abandon de Gaulle in favor of another more agreeable French leader.

At the same time, the Roosevelt administration had embarked, with Churchill’s quiet agreement, on a course to identify another prominent Frenchman who might supersede de Gaulle as the leader of the Free French. Further overtures to Weygand were thwarted when the general voiced his lasting allegiance to Pétain and evaporated when the Germans demanded his recall to France following the Torch landings.

The Americans then settled on General Henri Giraud, under whom de Gaulle had served at Metz in 1938. Giraud had escaped from a German prison and made his way to Vichy, where he declared his support for Pétain in glowing terms. Giraud was contacted by Allied agents, and heated negotiations ensued, with Giraud finally withdrawing his demand that he be placed in command of all Allied forces landing in North Africa. He agreed to command only French troops and to attempt to halt any Vichy resistance to the Torch landings. In exchange, he would be named governor general of North Africa.

It turned out that Giraud was every bit as difficult to deal with as de Gaulle might have been. To complicate matters, Admiral Darlan, commander of all Vichy armed forces, was coincidentally in Algiers on the day of the Torch landings. He had visited his son, who was suffering from polio, and his presence there did trump, to a great extent, any authority Giraud might attempt to exert over Vichy forces.

De Gaulle, meanwhile, had been made aware as early as August that something was afoot in North Africa. That warning may have come from the Soviets, who formally recognized the French National Committee as the “executive body” of Fighting France with the authority to organize French participation in the war.

On the morning of November 8, de Gaulle was awakened in London to the news of the Torch landings. “I hope the Vichy people will fling them into the sea! You can’t break into France and get away with it!” he snarled.

It fell to Churchill to brief the Fighting French leader on what was taking place, and by the time of their lunch appointment at Chequers, de Gaulle had cooled down a bit. In his memoirs, he recalled Churchill explaining, “We were forced to accept it. You can be sure that we are not in any way renouncing our agreements with you. As the business takes on its full extension, we British are to come into action. Then we shall have our word to say. It will be to support you. You were with us during the worst moments of the war. We shall not abandon you when the horizon clears.”

De Gaulle explained in a meeting with the National Committee that Churchill assured him that Giraud would play only a military role; however, it cannot be fully accepted that the politically astute de Gaulle was willing to simply take Churchill at his word. The Americans were running this show, and their man was Giraud. The days ahead might find de Gaulle without standing, and he knew it.

When he took to the BBC microphone on the evening of November 8, 1942, de Gaulle had completely changed his tune from the anger of the morning. It was evident that the liberation of France had begun with this offensive in North Africa. His comments were both reflective of his conviction that the future still held a prominent role for him and of the fact that the rank and file of the Fighting French and the French people as a whole needed a leader to stand firm.

“The Allies of France have undertaken to draw French North Africa into the war of liberation,” he remarked.

“They are beginning to land enormous forces there. It is a question of so ordering matters that our Algeria, our Morocco and our Tunisia form the base, the beginning point for the liberation of France. Our American allies are at the head of this enterprise.

“The moment is very well chosen. Our British allies, seconded by the French troops, have just expelled the Germans and Italians from Egypt and they are making their way into Cyrenaica. Our Russian allies have definitively broken the enemy’s supreme offensive. The French people, gathered together in resistance, are only waiting for the moment to rise up as a whole. So French leaders, soldiers, sailors, airmen, officials, and colonists rise up now! Help our allies!

“Come! The great moment is here. This is the time for common sense and courage. Everywhere the enemy is staggering and giving way. Frenchmen of North Africa, let us, through you, return to action from one end of the Mediterranean to the other. Then, the war will be won, and won thanks to France.”

The Allied landings in North Africa were met with varying degrees of resistance, and after nearly three days of fighting negotiations with Vichy France’s Admiral Darlan ended in a cease-fire. However, the deal brokered by General Mark Clark, chief of staff to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the overall Allied commander, raised a considerable degree of ire. Darlan was to be installed as the High Commissioner of France for North and West Africa with Giraud as his military commander.

Eisenhower had seen what was coming and told his senior commanders that he would accept responsibility for the political fallout that was certain to follow. Darlan was mistrusted and had commanded Vichy forces that had fired upon Allied troops—not to mention that de Gaulle was to once again be left out of the political picture. The Darlan fiasco hung like a cloud over the Allied governments, and sharp criticism was raised from every quarter. Although his motive remains unclear, a young assassin, Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle, shot Darlan twice as he entered his office on December 24, killing him and removing a major embarrassment.

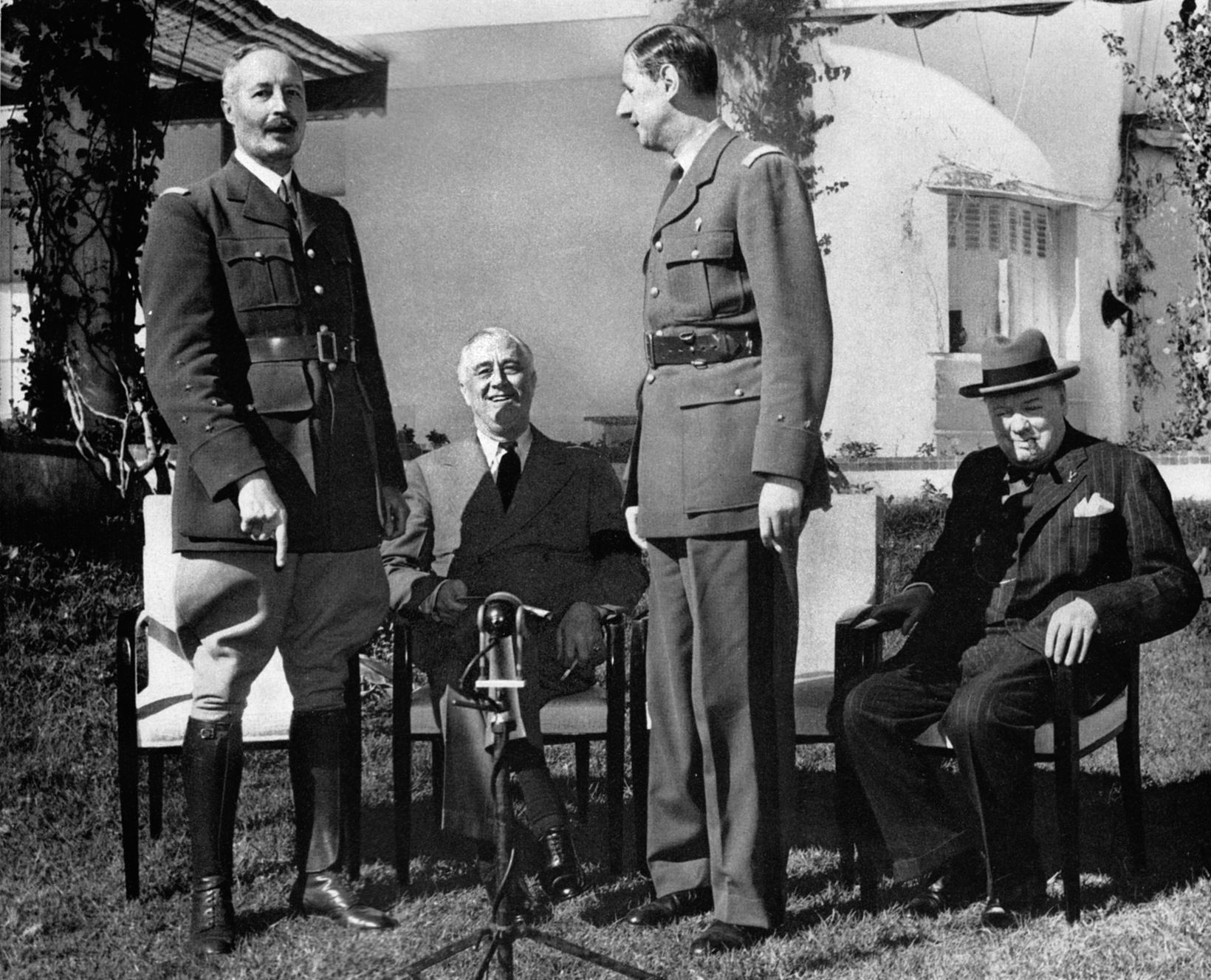

Darlan’s body was barely cold when Giraud was installed as civil and military commander in French North Africa. Immediately, de Gaulle began to push for a meeting of the two French leaders to discuss the future. However, while Giraud delayed, Churchill and Roosevelt decided to meet at Casablanca and invited both Frenchmen to join them. When de Gaulle declined, Churchill twisted his arm, threatening to cut off financial support of the French National Committee if he refused. When he did come to Casablanca, Giraud had already been present there for five days. Roosevelt chided Churchill that he had been able to produce the bridegroom, Giraud, but that Churchill was having difficulty coaxing the bride, de Gaulle, to the altar. When the conference was over, there had been no shotgun wedding.

De Gaulle arrived on January 22 and was presented with a proposal that a council be formed with Giraud, de Gaulle, and General Alphonse Georges, a prominent officer in North Africa who had refused to swear allegiance to Vichy, serving as copresidents. The council would include old Vichy enemies of de Gaulle, including Nogues and Boisson, who had resisted at Dakar and during the Torch landings. De Gaulle refused such a proposal, which would in effect have given Free France over to Giraud, the vassal of Britain and the United States.

In an attempt to salvage something, Roosevelt asked de Gaulle if he would at least agree to be photographed shaking hands with Giraud. When the shutter clicked, one of the more famous images of World War II was preserved, and the look of disdain on de Gaulle’s face is readily apparent. Subsequently, the two Frenchmen did agree to exchange liaison officers.

For de Gaulle, the meeting at Casablanca had been an exercise in personal resolve. He had refused to buckle under pressure from Roosevelt and Churchill, and he had won a foothold in North Africa. In reference to Giraud, he had measured the man. During the months to follow, Giraud would prove no match for the politically savvy de Gaulle.

By March, support for Giraud among the population of North Africa and within the French National Committee had eroded substantially, and when he cabled de Gaulle to request a meeting to discuss a unified French leadership it was de Gaulle who advised that the proposal of a copresidency put forward at Casablanca was as dead as Darlan. Early 1943 marked the rising tide of Charles de Gaulle. The resistance movement within France had grown steadily under the leadership of Jean Moulin, and when the two conferred in London in February plans were set in motion to convene the National Council of the Resistance, pledged to the support of the Free French.

Just as heartening, the Germans and Italians were expelled from North Africa in May, and the Frenchmen under arms there numbered 450,000. The Free French units there had actively participated in the fighting and were well respected for their contribution to the victory. Thus, the leader of Free France was well positioned to come to North Africa on his own terms rather than being summoned by another individual of greater perceived stature.

Churchill was still under pressure from Washington to dump de Gaulle, and the prime minister was still smarting from the intransigence of the Frenchman at Casablanca. The extent of his exasperation was such that he confined de Gaulle to London, restricted his access to the BBC, and even requested that the War Cabinet sanction a break with the French National Committee as long as de Gaulle was at its head. The request was denied, and it was plain to most observers who were close to the situation that time was running out for Giraud.

Roosevelt, too, had been vexed by the stubborn de Gaulle. In mid-May, he cabled Churchill the following: “I am fed up with de Gaulle and the secret personal and political machinations of that committee in the last few days indicates that there is no possibility of our working with him. I am absolutely convinced that he has been and is now injuring our war effort and that he is a very dangerous threat to us. The time has arrived when we must break with him. It is an intolerable situation. We must have someone whom we can completely and wholly trust.”

Roosevelt was continually astounded that de Gaulle could assert any authority whatsoever. His country had been conquered. He had depended on the goodwill of others. France had lost control of its own destiny. The government at Vichy represented Roosevelt’s idea of France—a nation that had capitulated and was to be rescued by the force of Allied arms.

Roosevelt saw de Gaulle as an impudent upstart who likened himself to the reincarnation of Joan of Arc and Clemenceau. The president’s superficial view of France and French history failed to comprehend the depth of the philosophical differences between the Fighting French and the collaborationists at Vichy. For de Gaulle, each slight, each insult was not only taken personally but also as an insult to the French nation. He was unapologetic, refusing to bend a knee or to beg for anything.

In turn, Roosevelt believed that de Gaulle had committed a serious affront with the occupation of St. Pierre and Miquelon. The president often openly questioned de Gaulle’s motivation, assessing the Fighting French leader as a would-be dictator and even a fascist sympathizer. Roosevelt did not trust de Gaulle, and the feeling was mutual. The president believed that the best approach to pressuring de Gaulle was through his British benefactors, and at times Churchill found himself caught between the rock of de Gaulle’s obstinance and the hard place of Roosevelt’s stubbornness.

Despite their recent wrangling, de Gaulle wrote to Churchill on May 27, 1943, “As I leave London for Algeria, where I am called by my difficult mission in the service of France, I look back over the long stage of nearly three years of war which Fighting France has accomplished side by side with Great Britain and based on British territory. I am more confident than ever in the victory of our two countries along with all their allies, and I am more convinced than ever that you personally will be the man of the days of glory, just as you were the man of the darkest hours.”

De Gaulle visited British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, who smiled and commented, “Do you know that you have caused us more difficulties than all our other European allies put together?” de Gaulle smiled in response, saying, “I don’t doubt it. France is a great power.”

The time had come for the headquarters of Free France to relocate to Algiers as de Gaulle set about consolidating power, leaving an outmaneuvered Giraud in his wake. In less than a week, the two announced the formation of a French Committee of National Liberation, with de Gaulle and Giraud as copresidents and a council of five others. However, when Giraud departed for a three-week visit to the United States de Gaulle attended parades and was received enthusiastically across French North Africa. With the Allied invasion of Sicily, he provided logistical support in Giraud’s absence.

By the time Giraud returned, de Gaulle had convinced the committee that his original plan, with himself as the political head of the committee and Giraud as the military commander, was the proper course. De Gaulle would be the committee chairman, and the copresidency would survive in name only. All this was accomplished by the end of July 1943. By the autumn, de Gaulle had consolidated power and constructed the basis for a provisional government over which he intended to assume authority in France following victory over the Nazis.

While the political jockeying continued, Allied armies were advancing on all fronts. The liberation of Sicily was followed, in September 1943, by Allied landings at Salerno on the Italian mainland, and Mussolini had been deposed two months earlier. The Soviet Red Army had won its victory at Stalingrad and embarked on a great offensive surge that would carry it all the way to Berlin. In the West, Britain and the United States had been planning an invasion of the European continent for months.

During that summer of victory, Yvonne and Anne relocated from London to a villa in the hills above Algiers. De Gaulle’s daughter Elizabeth worked in the office of the National Committee, while his son, Philippe, served with the Free French navy.

Just as he had been excluded from official planning and discussion for the North African operation, de Gaulle was only on the periphery of the negotiations with Italian authorities that concluded with that nation officially switching to the Allied side. In addition, plans were under way for a military government in France after the war, under the administration of Great Britain and the United States. For de Gaulle, the intent was plain. France was to have a secondary role in the postwar world. Even Stalin had stated previously that he attached little importance to the Fighting French, which did not represent a great power and were of no consequence to the Soviet Union.

True to form, Roosevelt blocked any detailed disclosure to de Gaulle of the plans for Operation Overlord, the D-Day invasion, and it was not until de Gaulle arrived in London on June 4, 1944, to confer with Churchill that any part of the plan for the liberation of Western Europe was shared with him, including plans for the future of the French government.

De Gaulle had no interest in discussing some cooperative arrangement with the British and Americans for the administration and government of liberated France. His Fighting French were the government. On that point, he would never yield. He also wanted to ensure that French troops, particularly the 2nd Armored Division under General Jacques Leclerc, should be equipped and landed in France as soon as possible to play some significant role in the liberation of Paris.

“Why do you seem to think that I am required to put myself up to Roosevelt as a candidate for power in France,” he told the prime minister. “The French government exists. I have nothing to ask of the United States of America, any more than I have of Great Britain.”

Churchill responded with equal ardor, “And what about you? How do you expect us, the British, to adopt a position separated from that of the United States? We are going to liberate Europe, but it is because the Americans are with us to do so. Any time we have to choose between Europe and the open seas, we shall always be for the open seas. Every time I have to choose between you and Roosevelt, I shall always choose Roosevelt.”

Following the audience with Churchill, de Gaulle visited the headquarters of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme Allied commander in Europe, and was shown the text of a radio message the general intended to deliver regarding a provisional government of France. De Gaulle rejected the statement out of hand, withheld the deployment of a cadre of French liaison officers that were to accompany the Allied invasion force, and did not participate in a joint declaration with representatives of other governments in exile in support of Overlord. Instead, he chose to address the French people alone on the BBC on the afternoon of June 6, 1944.

“The supreme battle has begun,” he said in a measured tone. “It is the battle in France, and it is the battle of France. France is going to fight this battle furiously. She is going to conduct it in due order. The clear, the sacred duty of the sons of France, wherever they are and whoever they are, is to fight the enemy with all the means at their disposal.

“The orders given by the French government and by the French leaders it has named for that purpose are to be obeyed exactly. The actions we carry out in the enemy’s rear are to be coordinated as closely as possible with those carried out at the same time by the Allied and French armies. Let none of those capable of action, either by arms or by destruction or by giving intelligence or by refusing to do work useful to the enemy, allow themselves to be made prisoner. Let them remove themselves beforehand from being seized and from being deported.

“The battle of France has begun. In the nation, the empire and the armies there is no longer anything but one single hope, the same for all. Behind the terribly heavy cloud of our blood and our tears here is the sun of our grandeur shining out once again.”

De Gaulle made no concessions. His intentions were clear, and during the spring of 1944 numerous governments chose to recognize the de facto leadership of France. Grudgingly, both Roosevelt and Churchill would come to the same conclusion. The leaders of Great Britain and the United States fumed, considering de Gaulle a hindrance and distraction to the business at hand. However, it was apparent that de Gaulle’s control of the French Resistance, his influence with the French forces in the field, and his popularity among the French people as a whole constituted a force with which to be reckoned. The headstrong Frenchman made plans to return to his homeland for the first time in four years. n

Michael E. Haskew is the editor of WWII History Magazine. He has authored and contributed to numerous books related to various aspects of World War II. This work is excerpted from his book De Gaulle: Leadership Lessons from the Defiant General, recently released by Palgrave Macmillan.

Join The Conversation

Comments