By Harry Yeide

While many in the English-speaking world have heard of Erwin Rommel and Heinz Guderian, few today know the name of Otto von Knobelsdorff, a German panzer general who commanded troops in battles every bit as pivotal as his contemporaries did, in quantity and quality, and who also fought against General George S. Patton, Jr.

Knobelsdorff was one of Hitler’s outstanding panzer commanders alongside Hasso von Manteuffel, Hermann Balck, Hermann Priess, and Max Simon. He held Patton at bay in Lorraine in the fall and winter of 1944. In the attack, the aggressive Knobelsdorff resembled Patton in many ways, but he had rich experience in waging defensive battles and retreats, a test of command that the great strategist Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke judged the most difficult of military operations and a test in which Patton never had to prove himself. There are several excellent accounts of the battle for Lorraine, where Knobelsdorff commanded First Army; this article will focus on his military career up to that point.

Otto von Knobelsdorff’s Old Prussian Lineage

Otto Heinrich Ernst von Knobelsdorff was born in Berlin on March 31, 1886, the progeny of an old Prussian military family. His father had been a major in the 12th Infantry Regiment, and his mother was born a von Manteuffel. After years being educated as a cadet at Bensberg and Gross-Lichtenfelde, Knobelsdorff in 1905 joined the Imperial Army’s Infantry Regiment Grossherzog von Sachsen (5th Thüringisches) Nr. 94 as an officer candidate. The young cadet was nearly a head shorter than most of the others around him, but he made up for it with drive. He was endowed with boundless energy, clear judgment, and a good sense of humor. He was also brave, friendly, and open.

Knobelsdorff was promoted to Leutnant (second lieutenant) in 1908 and to Oberleutnant (first lieutenant in August 1914, having become the regimental adjutant in January. That year, he married Alasandria Freiin von Korff-Schmising, who bore him two sons and one daughter.

Knobelsdorff’s regiment, part of the 83rd Infantry Brigade, 38th Infantry Division, went to war on the Western Front in August 1914, pushed through the Ardennes with XI Corps, and reached Namur, Belgium. The corps then entrained for the east after the Russian invasion of East Prussia that same month and participated in the Ninth Army’s counterattack. There on the Eastern Front, Knobelsdorff fought at the Masurian Lakes, Goldap, Opatów, and Ivangorod, and he experienced the retreat of his own army. In October, the corps joined the Austrian First Army to stiffen its fighting ability. Knobelsdorff remained on the Eastern Front until September 1915 and got to enjoy a stunning return to success for German arms.

The 38th Division entrained for France on September 25, where it absorbed new manpower and took up a quiet sector of the front at Tracy le Val until May 1916. On March 22, Knobelsdorff received a promotion to hauptmann (captain) for his bravery. Between November 1915 and April 1916, Knobelsdorff commanded a rifle company and, temporarily, first one then another battalion. In May the division moved to the Verdun sector, where it fought for five months. After a brief rest recruiting for the division, Knobelsdorff took command of a separate infantry battalion that worked with the 94th and 95th Infantry Regiments from the summer of 1917 until October. The 94th Regiment waged the epic struggle for Hill 304 and “Dead Man’s Hill” and held them until August 24—the last remaining German strongpoints at Verdun to fall into French hands.

The 38th Division suffered heavy casualties, including 52 percent of the infantry. In October, the division moved to the Somme, where again it lost many of its men, but Knobelsdorff was moved up to brigade adjutant and was no longer on the front line.

In November 1917, Knobelsdorff set off to fill a string of staff jobs at Army Group B, VII Corps, the 200th Infantry and 1st Guards Infantry Divisions, the Bug Army, and the 242d Infantry Division. It was in this last assignment, while working as chief of supply, that Knobelsdorff was seriously wounded on October 28, 1918, less than two weeks before the end of the war.

Otto von Knobelsdorff followed a diverse and educational path after the Armistice. He returned to the 94th Regiment and served as a company commander in several other regiments, held staff jobs in two artillery groups, and took charge of a squadron of the 9th Mounted Regiment for a year in 1928. He then took command of the 102nd Infantry Regiment in 1935. A newly minted generalmajor (brigadier general), he commanded the fortifications around Oppeln, east of Dresden near the Polish border, just before war broke out in September 1939.

Leading From the Front

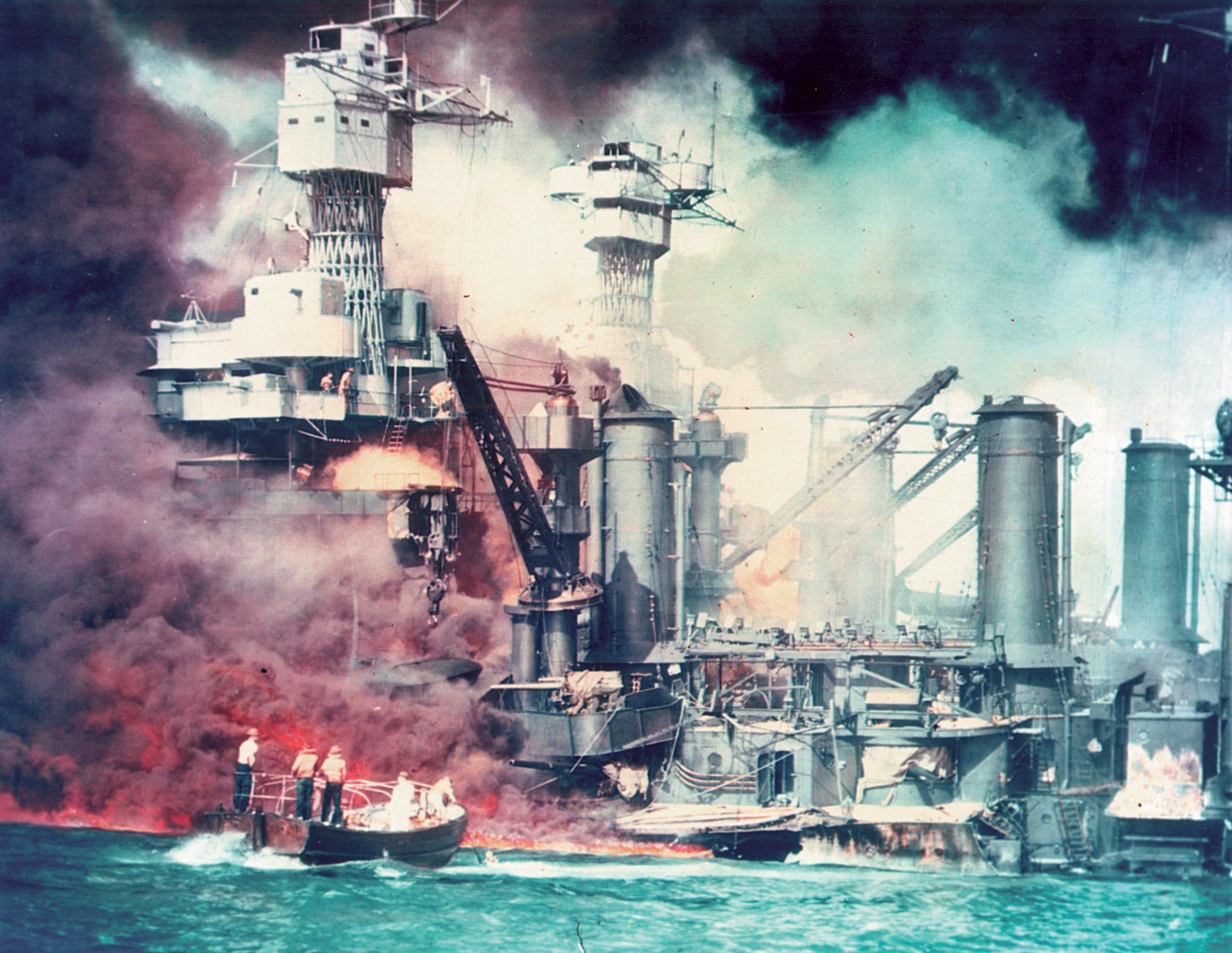

The German offensive in Poland on September 1, 1939, was a showpiece for Blitzkrieg (lightning war) and destroyed the Polish Army in about two weeks. Fourteen mechanized or partially mechanized divisions supported by an overwhelming Luftwaffe air arm were decisive in the stunning success, though some 40 regular infantry divisions also took part.

Knobelsdorff commanded the 102nd Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division in the campaign. The division’s records were destroyed in a fire, so nothing is known about his performance in Poland except that it was good enough to earn him a divisional command in France.

Knobelsdorff took over the 19th Infantry Division on February 4, 1940. The division, part of XI Corps, was still in training on May 9 when the code word “Hindenburg 10 05 35” arrived. Generalleutnant (Maj. Gen.) Joachim von Kortzfleisch, commanding the corps, briefly addressed his subordinate officers: “Germany will be victorious, because it must be victorious!” Knobelsdorff and the others responded with a hearty “Sieg Heil!” to the Führer and the Fatherland. The fact that Knobelsdorff for a while sported a Hitler-type moustache suggests that he was a Nazi believer, and one personnel evaluation noted that he was a firm National Socialist.

In less than four hours, Knobelsdorff had his men on the march to their assembly area, straight from maneuvers. Knobelsdorff was well pleased with the excellent organization and high morale that he saw among his troops. By 2 am, Knobelsdorff’s combat elements had closed to the Dutch border. X-hour was 5:35 am, XI Corps informed him. The invasion began on the dot.

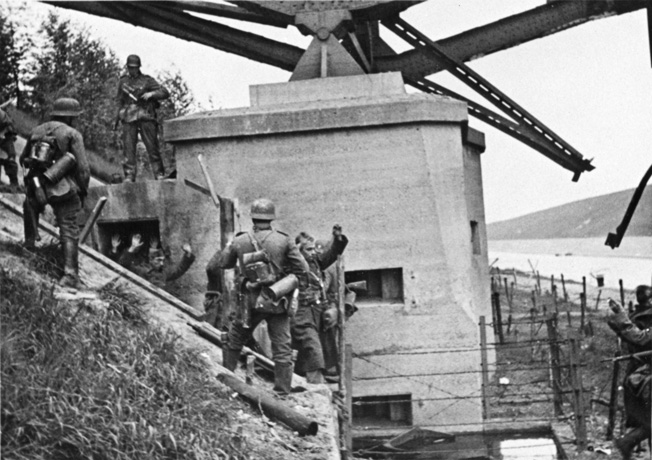

The Dutch offered no resistance until the Germans reached Maasniel, where a Dutch motorcycle unit claimed the first casualties. The 2nd Battalion, 59th Infantry Regiment, supported by the 5th Panzer Platoon, reached the railroad bridge over the Maas River only to find it destroyed. As the panzers sat, Dutch gunners in bunkers on the far bank scored several direct hits and caused heavy casualties. By 6:45, the rest of the division closed to the Maas, but by then every single span had been blown. Heavy fire stopped every attempt to cross.

Knobelsdorff was to show daring and aggressive instincts from the first hours of battle. The general drove to the front line at the bridge at Roermond about 7 am and surveyed the scene. The Dutch were brilliantly camouflaged, and they had made excellent use of invisible bunkers set well back to place raking fire on his flanks. Knobelsdorff ordered reconnaissance to identify the Dutch positions so they could be shelled, and he personally oversaw the deployment of heavy antitank guns, pointing out to the commanding officer of the division’s artillery regiment which targets he wanted blasted. He also instructed his chief of engineers to hustle forward river crossing gear to replace what had been destroyed.

Briefly returning to his headquarters to report the situation to XI Corps, Knobelsdorff made his way back to Roermond by 9 am to find that, under the cover of the heavy weapons, some of his reconnaissance troops were across the Maas. About 10:00, an antitank gun knocked out the Dutch bunker at the west end of the damaged Roermond bridge, and infantry immediately clambered across the girders. Elsewhere, the division’s crossings succeeded under the cover of artillery fire. With Roermond secured and nearly 600 prisoners in hand, Knobelsdorff ordered two battalions to continue to the Belgian border and prepare to assault the bunkers there.

Fighting Against “The Hated English”

Knobelsdorff led from the front again the next day, directing his battalions toward objectives on the Albert Canal. Only individual Belgian soldiers were encountered, and they inevitably surrendered. The Belgians, however, were well entrenched on the far side of the canal. Late on May 11, Knobelsdorff issued a special order of the day praising his men, who had created a breakthrough and advanced 45 miles in only two days.

Kept on a leash by XI Corps while the divisions to the left and right crossed the Albert Canal, the 19th Division finally got its attack orders on the 13th and pushed across. Knobelsdorff reached the far bank on the heels of the assault troops and immediately took control.

By the 17th, the division was on the northern outskirts of Brussels, having fought the British for the preceding two days; the 14th Division, to Knobelsdorff’s left, occupied the Belgian capital on May 18. Brigadier A.J. Clifton’s 2nd Armored Reconnaissance Brigade, covering the withdrawal of II British Corps southwest of Brussels, encountered Knobelsdorff’s reconnaissance elements near Assche at about 11 am.

The British were trying to link up with Belgian troops when they unexpectedly ran into the German forces. The British contingent, consisting of the 5th Inniskilling Dragoon Guards, 15th/19th The Kings Royal Hussars, 4th Gordon Highlanders (a machine-gun battalion), 32nd Army Field Regiment, and the 14th Antitank Regiment discovered the “enemy were round and between” them and their supporting artillery and machine guns.

Fighting raged throughout the morning. Antitank guns from the 19th Panzerjäger Abteilung (Antitank Battalion) had been positioned with fields of fire overlooking the routes utilized by the British, and Knobelsdorff rushed to the scene with a company of heavy antitank guns. A battalion each of infantry and artillery arrived, and in a wild melée Knobelsdorff and his men engaged the British with cannons, pistols, hand grenades, antitank rifles, and antitank guns. The British reconnaissance vehicles became stuck in soft ground, and the Germans gunned down the fleeing crews; several sections of the 15th/19th Hussars were completely wiped out during the fighting.

British orders to withdraw were issued at noon, but they failed to reach some units for several hours. By then, the Germans had surrounded them. When the shooting stopped at about 4 pm, 48 British reconnaissance tanks had been knocked out, plus 22 Bren carriers. On the field of battle, Knobelsdorff issued Iron Crosses to those he had seen perform with outstanding courage.

Knobelsdorff obviously had a hand in the drafting of his division’s Kriegstagebuch (war diary; he signed the document) because his personal actions are well covered, and a bit of his personal viewpoint appears to creep in. An entry on May 19 refers to “the hated English before us,” which suggests that he fought the war with passion rather than professional detachment.

Knobelsdorff had already proved himself an aggressive commander in the attack, even though he commanded an infantry division. At times, he rode with his leading reconnaissance troops so that he could survey the terrain. One British prisoner told his captors, “You are motorized troops with parachutists, otherwise you could not possibly be here already!”

The race ended along the Scheldt River, where from May 20-22, XI Corps launched fruitless and costly frontal attacks against a determined British enemy well backed by artillery; reconnaissance on the 23rd revealed that the enemy had slipped away. Five days later, word reached Knobelsdorff’s headquarters that a cease-fire with the Belgians had been declared. The British continued to fight, however, and the 19th Division did not cease combat operations until the 30th. The division’s fighting days were over in the West.

But Knobelsdorff’s glory days were not. On June 15 came the surprising news that Paris had surrendered, and the 19th Division received orders to enter the city and secure it. Knobelsdorff thereby became the conqueror of Paris. His columns marched through the city on the 16th, and he held regimental formations on the Place de la République and the Place des Nations. The 30th Infantry Division simultaneously entered from the west and remained as the occupation force.

Knobelsdorff’s performance review in late 1940 described him as an extremely energetic and forceful personality with tremendous influence on his troops. He had proved himself in the French campaign in a superior manner.

The Drive to Moscow

Knobelsdorff was promoted to generalleutnant (major general) on December 1, 1940, shortly after his 19th Infantry Division had been converted into the 19th Panzer Division and received Czech 38(t) tanks. The able general picked up the craft of armored warfare with remarkable speed. The division’s Kriegstagebuch for the period from the invasion of the Soviet Union through September 1942 was destroyed by enemy action. Fortunately, however, Knobelsdorff wrote a history of the division’s operations.

Knobelsdorff’s tanks formed part of Guderian’s 2nd Panzer Group and attacked into the Soviet zone in Poland on June 22, 1941. After following the 12th Panzer Division for several days, which meant fighting all the bypassed Soviet troops, the 19th Panzer Division was ordered by LVII Corps to advance to Minsk post haste. Superior Soviet forces, however, were attempting to break out northward across Knobelsdorff’s line of march, and most of his column became engulfed in a furious defensive battle lasting from June 25-29, when an infantry division finally arrived to relieve the panzers. The corps headquarters offered no complaints, as it had been traveling in the center of Knobelsdorff’s march column and had barely been saved from destruction by his tanks.

After a week of fierce close-in fighting around Polotsk in Belarus, Knobelsdorff on July 13 began his first classic operation as a panzer general, attacking northeastward into Russia proper through Nevel to Velikiye Luki, a major rail center deep in the Soviet rear, a distance of nearly 100 miles.

Fighting through sandy terrain that slowed vehicles, as did many lakes and swamps, Knobelsdorff two days later took Nevel with a skillfully executed pincer attack. The capture of the town severed the Soviets’ Kiev-Leningrad supply route. The Russians had destroyed a bridge there and, during the first night, truck after Soviet truck, operating without headlights, drove off the span and crashed into the ravine below. Soviet tanks then moved up and probed the city from the east, and the fighting ignited part of the city and, much to Knobelsdorff’s dismay, burned down a vodka factory.

The next day, Knobelsdorff pushed on, moving so quickly that his troops captured bridge after bridge before the surprised Soviets could destroy them. Knobelsdorff’s account of his time as division commander shows that he was a model panzer leader, nearly always advancing with his foremost elements to take control of the situation immediately when the unexpected occurred.

On July 17, the German spearhead encountered an antitank screen south of Velikiye Luki, and Knobelsdorff smoothly brought his panzers forward and seized the dominant high ground south of the city. He then pushed his infantry forward and took the city quarter by quarter. The Soviets counterattacked the next day and cut Knobelsdorff’s only road to his rear. Faced with the threat of encirclement, he struck back furiously with tanks and an infantry regiment and restored the situation by mid-afternoon.

During the first six weeks of the Eastern campaign, Knobelsdorff’s division had covered 800 miles of ground, which he boasted was “unique in Prussian-German military history.”

Knobelsdorff nearly reached Moscow. Joining Army Group Center’s renewed offensive toward the Soviet capital, the 19th Panzer Division was among the first to penetrate the concrete bunkers and antitank obstacles of Moscow’s outer defenses, maneuvering through seemingly impassable terrain to take the Soviet defenses from the rear near Ilinskoye on October 16. Knobelsdorff was overseeing the elimination of heavy bunkers with direct artillery fire when the commanding general of Fourth Army, Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal) Günther von Kluge, appeared to personally praise the division’s performance.

Riding with his panzer regiment, which advanced alone until other mobile elements could recover their trucks and catch up, Knobelsdorff on the 18th pressed on toward Moscow and captured two bridges over the Protva River intact. Luftwaffe planes buzzed overhead, constantly in communication and able to alert the ground troops of Soviet forces in their path. The lead company, blasting away, charged through antitank fire to seize the next bridge. Knobelsdorff thought it his panzer regiment’s greatest day.

The division’s own infantry caught up on the 19th, but the neighboring infantry divisions were still stuck 40 miles to the rear at the Moscow defense line. The Soviets attacked the exposed panzer division from the front and flanks. Knobelsdorff reported that without tank reinforcements his division was too weakened to advance farther. The 98th Infantry Division finally worked its way forward, and Knobelsdorff’s panzers crossed the Nara River. But that was it. The German drive had exhausted itself. Knobelsdorff was but 40 miles southwest of Moscow. Winter arrived with a vengeance on the 27th, and the temperature dropped to 40 degrees below zero centigrade.

Gruppe General von Knobelsdorff

The first Soviet counteroffensive of the war blasted out of the ice and snow on December 5 along a 500-mile front, primarily against Army Group Center, which reeled back from the outskirts of Moscow. Knobelsdorff’s divisional history suggests that he began to lose faith in his Führer, who had continued to throw exhausted troops fruitlessly against Moscow’s defenses during November, wasted irreplaceable manpower, and now issued stand-fast orders against the pleas of his senior generals. After the war, Knobelsdorff’s interrogators recorded that he was an outspoken critic of the Nazi Party.

Despite orders to the contrary from the high command, Fourth Army pulled back from its forward positions near Moscow in late December; Soviet cavalry had gotten into the rear areas and threatened to cut off XII and XIII Corps. The much weakened 19th Panzer Division attacked on December 28 through deep snow to clear an escape route for the two corps. Passing the battlefields where he had lost so many of his men, Knobelsdorff recorded, “We were ashamed before them to have to retreat, those who had only known attack and success.”

Kluge took command of the disintegrating Army Group Center on December 19. Hitler had just taken direct command of the army. Kluge wanted to pull back, but Hitler stiffened his spine and averted disaster. Most German records from this chaotic period went missing, but it is known that Knobelsdorff was evacuated due to illness on January 6, 1942.

On the frigid night of January 7, 1942, a massive blow struck the right wing of Army Group North, and a month of fierce fighting ensued. By February 8, Soviet pincers had surrounded six divisions of Sixteenth Army’s II Corps in the Demjansk pocket, including the SS Totenkopf Division. (Two officers in that division—Oberführer Max Simon and Standartenführer (Colonel) Hermann Priess—would survive and later fight at the head of XIII SS Corps under Knobelsdorff’s command in Lorraine.)

Knobelsdorff returned to duty and on May 1 took command of Sixteenth Army’s X Corps at the northern end of the Eastern Front near Lake Ilmen. Though this was primarily an infantry corps, Knobelsdorff was a fitting commander for it because a day earlier the corps had launched an attack with effective artillery and close air support against a thinly held stretch of the Soviet line at Kobylkino to meet a corresponding attack by II Corps’ Totenkopf Division at Demjansk, which had just reestablished contact with the rest of Sixteenth Army. Knobelsdorff’s troops fought their way into Cholm on May 5 and established a firm link with the besieged corps. The Führer was watching the battle intently and urged that the corridor to II Corps be widened.

Only one month later, on June 1, Knobelsdorff was transferred to command the beleaguered II Corps. His fight there was mainly a defensive one, though he jabbed westward at the Soviets with the battered Totenkopf Division, fighting to widen the corridor. Knobelsdorff successfully defended the Demjansk salient over the summer against fierce Soviet efforts to eliminate it. As autumn arrived, the general’s corps, now labeled Gruppe General von Knobelsdorff, appeared twice in the Army high command’s daily briefing for Hitler in late September and early October, attacking and gaining ground.

Knobelsdorff returned to mobile warfare October 10, taking charge of XXIV Panzer Corps, which was part of the Second Hungarian Army in Army Group B, deployed on the Don River south of Voronezh. No corps, army, or army group records have survived from this period, so nothing is known about Knobelsdorff’s actions. Given the importance of his next assignment, however, he must have done well.

Plugging the Soviet Breakthrough

By December 1942, the situation along the Chir River northwest of Stalingrad looked grim for the Germans. The Soviets were on the attack and creating an unbreakable ring around Sixth Army at Stalingrad. Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal) Erich von Manstein’s newly established Army Group Don had taken over the Chir River sector on November 28, nine days after the Soviets launched their offensive. Friedrich-Wilhelm von Mellenthin was just arriving at XLVIII Panzer Corps headquarters, the stiffener for the Romanian Third Army, to take up duties as chief of staff.

Looking at the situation map at the Führer’s Wolfschanze headquarters in East Prussia on November 27 while in transit to the front, Mellenthin recalled, “I tried to find the location of my XLVIII Panzer Corps, but there were so many arrows showing breakthroughs and encirclements that this was far from easy. In fact, on 27 November the XLVIII Panzer Corps was itself encircled in a so-called ‘small cauldron’ to the northwest of Kalach.”

By the time Mellenthin arrived, the corps had fought free and, along with the rest of the army, had taken a line along the west bank of the Chir, which was assessed to be a tank obstacle except for several fords. Generalmajor (Brig. Gen.) Hans Cramer, an experienced panzer general who had fought beside Field Marshal Erwin Rommel in North Africa, took temporary command of the corps on November 30. The corps, consisting of the 22nd Panzer, 1st Romanian Armored, and 7th Romanian Infantry Divisions, was just wrapping up a desperate and successful fight to stop the Soviet thrust through the Romanian front by attacking its flanks.

On December 3, Cramer handed over his stretch of the line to II Romanian Corps. The panzer corps was to receive the 11th Panzer, 336th Infantry, and 7th Luftwaffe Field Divisions and was to attack on Fourth Panzer Army’s left in a planned operation to relieve Sixth Army stranded at Stalingrad; elements of all three divisions were already arriving. But it had been snowing so heavily that movement was difficult.

On December 5, Knobelsdorff arrived to replace Cramer. The decision to move him from XXIV Panzer Corps on November 30 was a sign of desperation because a large Soviet buildup east of the Don facing Second Hungarian Army showed that the Soviets would soon strike there, too. Knobelsdorff, Mellenthin found, “was a man of remarkable attainments, flexible and broad-minded, and highly esteemed by all members of his staff.”

Knobelsdorff was just in time to meet the Fifth Tank Army, which was crossing the Chir in force. The key German strongpoint at Rytschov was just barely fending off tank-supported attacks and had lost two of its 88mm multipurpose guns.

Generalmajor (Brig. Gen.) Hermann Balck, who would later be Knobelsdorff’s superior as the head of Army Group G in Lorraine, arrived on the Chir at the head of his 11th Panzer Division on December 6, just as the Soviet I Tank Corps was knocking a hole in the XLVIII Panzer Corps line of isolated Kampfgruppen (battle groups), despite intervention by the newly arrived 336th Infantry Division. Balck went to corps headquarters about noon, and Knobelsdorff ordered him to seal the breach. He told Balck to rush his antitank guns and a panzergrenadier battalion to Rytschov.

Knobelsdorff’s headquarters called at 9 am the next day with the alarming news that 50 Soviet T-34 tanks had burst through the line of a regiment of the 7th Luftwaffe Field Division where it joined the 336th Infantry Division. The latter division was pushing its right wing forward and had its strength concentrated there, and it would be a short time before the hole widened to three miles and the Soviets would reach the artillery positions. If the Soviets pivoted, they would take the 336th Infantry Division in the flank. The 336th Division’s commanding general begged Knobelsdorff for help from Balck’s panzer regiment.

At 9:15 am, Fourth Panzer Army approved Knobelsdorff’s request to counterattack with Balck’s panzers, and 10 minutes later his orders reached Balck. The weather was improving slightly, and the Luftwaffe, which had been grounded all morning, ordered every available plane into the air. The 11th Panzer Division was rested and ready, having enjoyed a relatively quiet November near Smolensk, but nearly a third of its vehicles had fallen out during the march north.

Balck acted with incredible speed, and his 15th Panzer Regiment arrived at the Soviet breakthrough by 10:45 am. The Soviets, meanwhile, were pushing more tanks, motorized infantry, and artillery—an estimated total of two infantry divisions and a tank brigade—into the hole. Knobelsdorff had lost contact with his infantry elements at the point of penetration, and at noon he ordered the rest of the 11th Panzer Division to follow the panzer regiment.

By 5 pm, the 110th and 111th Panzergrenadier Regiments and a motorcycle battalion arrived and sealed off the road to the south that led into the 336th Division’s rear. The counterattack blocked the Soviet advance, but Knobelsdorff ordered the division to stop pushing forward until it could gather its strength.

Rather than make a frontal attack, Knobelsdorff wanted to attack the next morning against the enemy’s flank and rear and issued orders to that effect. The 11th Panzer Division was to keep its forces tightly together. Mellenthin later implied this had been Balck’s idea, but XLVIII Panzer Corps records suggest that was not the case. Still, under the German practice of Auftragstaktik (mission-type orders), Balck had a free hand in deciding how to execute the orders.

Balck struck at 4:30 am and conducted a brilliant slashing panzer drive across the Soviet rear––the maneuver made all the more effective because the Soviets had committed 50 of their tanks against the left wing of the 336th Infantry Division where they could be cut off.

At first, progress was slow against a strong defense. The rolling hills were not tank friendly and offered the defenders good concealment. The panzers nevertheless caught the Soviet armor in the flank, destroyed many of the tanks, and pushed on. Then the 2nd Panzer Battalion caught a motorized infantry column in the open, and the Soviet defenses began to unravel. Stukas, meanwhile, crushed a Soviet breakthrough on the 336th Infantry Division’s left, and the Luftwaffe conducted effective attacks across the corps front.

By 2:30 pm, the 11th Panzer Division had cut off the Soviet troops that had broken through. When the day was over, Balck had nearly destroyed the enemy corps, including most of the 46 tanks counted on the battlefield. His own losses had been slight. “With the coming of dark,” Knobelsdorff’s operations staff recorded, “the corps can look back on a great success.”

Until December 22, Knobelsdorff had used the 11th Panzer Division like a rapier. Balck, moving night and day, fell upon one Soviet penetration after another and destroyed nearly all of them. Working hand in glove with two infantry divisions, Balck gave a Kriegsakademie-perfect display of flexible defense.

“Pursue the Defeated Enemy”

Despite Knobelsdorff’s and Balck’s successes, Germany faced a strategic disaster in the East in early 1943. The main point of the Soviet winter offensive was aimed at the southern end of the German front. As of late January, Army Group A’s First Panzer Army was hurriedly withdrawing from the Caucasus through Rostov while Manstein’s battered Army Group Don struggled to keep the escape route open.

In Stalingrad, Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal) Friedrich von Paulus’s 270,000-man Sixth Army capitulated on February 1, which released considerable Soviet forces. Army Group B was in tatters, which exposed the entire southern wing of the German front to potential envelopment by forces driving through Kharkov and swinging down to the Sea of Azov. Army Group Don estimated that the Soviets on its front held a manpower advantage of eight to one.

Manstein, in an argument with Hitler on February 6, won permission to withdraw from the lower Don and eastern Donets basin to the Mius River line and to concentrate First and Fourth Panzer Armies on his left wing. Manstein’s strategic shift was just in time—three Soviet armies took Kharkov on Manstein’s left in mid-February.

The Soviet offensive finally petered out in late February, and the Germans were able to establish a line along the Dniepr River capable of holding back the now exhausted Soviet troops, who had advanced some 300 miles.

The brilliant Manstein scripted the final scene in orders he issued on February 19. First and Fourth Panzer Armies and Army Detachment Kempf (controlling the corps southwest of Kharkov), reinforced by refreshed panzer divisions, rushed forward by rail, attacked the Soviet Sixth Army, First Guards Army, and Popov’s Mobile Group from two directions southwest of Kharkov and destroyed Sixth Army and Popov’s Group and savaged the Third Tank Army, which had entered the battle. Knobelsdorff’s XLVIII Panzer Corps and Obergruppenführer (Lt. Gen.) Paul Hausser’s SS Panzer Corps played the key roles in this crushing counterblow.

As late as the 25th, Soviet troops were fighting fiercely and receiving reinforcements, but only two days later Generaloberst (Col. Gen.) Hermann Hoth’s orders from Fourth Panzer Army to Knobelsdorff were: “Pursue the defeated enemy.”

Operation Citadel: Germany’s Gettysburg

Knobelsdorff played a leading part in Operation Citadel, the German attempt to eliminate a large Soviet salient at Kursk in July 1943. The Battle of Kursk was Germany’s Gettysburg, the last time Hitler would launch a major offensive in the East. The scale was gargantuan, by most accounts the largest tank battle of the war.

But first Manstein’s renamed Army Group South struck northward toward Kharkov on February 28 with Hausser’s SS Panzer Corps on the left and Knobelsdorff’s XLVIII Panzer Corps on the right. Manstein’s blow completely surprised the Soviets and took three corps opposite Army Detachment Kempf in the rear. The Luftwaffe’s Fourth Air Fleet, under General Wolfram von Richthofen, flew 1,000 sorties per day and for the last time protected a major ground operation through complete dominance of the skies.

Manstein pressed on toward Kharkov on March 5 with Hausser’s corps screened on its right by Knobelsdorff and on its left by Army Detachment Kempf’s Corps Raus. Hausser advanced in a wide arc north of Kharkov and enveloped the city, cutting off the enemy’s retreat, while the Grossdeutschland Division advanced on Belgorod; the corps secured Kharkov after three days of costly street fighting. The bulk of the SS Corps advanced to Belgorod starting March 16, and the 2nd SS Das Reich Panzergrenadier Division linked up with the Grossdeutschland Division. This created the launching pad for the next great German offensive at Kursk.

British historian Sir Basil Liddell-Hart called the counterstroke at Kharkov “the most brilliant operational performance of Manstein’s career, and one of the most masterly in the whole course of military history.” Knobelsdorff had been a key lieutenant under this exceptional commander in this extraordinary historical event.

Following the victory at Kharkov, German divisions had a breather to refit thanks to Soviet exhaustion and the spring rains that turned Russia into a sea of mud. Hitler wanted to regain the initiative on the Eastern Front completely. Hitler’s first order for Operation Citadel, issued on April 15, specified that “the best commanders” be assigned to the main effort. Knobelsdorff’s name evidently was on that list.

The Soviet salient at Kursk was the natural objective, being a bite big enough to stall the Soviets and, it appeared, small enough for the Germans to chew. An early attack—initially set for May 25—would gain the element of surprise and catch the Soviets before they could fully recover. But delays in the delivery of tanks, especially the new Mark V Panther, led to postponement. Hitler finally set the attack date for July 5.

The plan was simple: Army Group Center was to attack southward with Ninth Army from Malo-Arkhangel’sk while Army Group South’s Fourth Panzer Army and Army Detachment Kempf struck northward from Belgorod. They were to meet on the heights north of Kursk and destroy trapped Soviet forces to the west. The southern group fielded five corps with nine panzer and panzergrenadier divisions and eight infantry divisions. Army Group Center fielded five corps with six panzer and 15 infantry divisions. The equipment, training, and morale of the units earmarked for the offensive were the highest they would ever be on the Eastern Front.

In the south, Fourth Panzer Army was to make the main thrust with Knobelsdorff’s XLVIII Panzer Corps on the left (3rd and 11th Panzer Divisions; the Grossdeutschland Panzergrenadier Division; 10th Panzer Brigade—the 51st and 52nd Panzer Battalions—with 188 factory-fresh Mark V Panthers; and elements of the 167th and 332nd Infantry Divisions) and II SS Panzer Corps (redesignated in April and consisting of the 1st SS Leibstandarte, 2nd Das Reich, and 3rd Totenkopf SS Panzergrenadier Divisions) on the right. Army Detachment Kempf (XI and III Panzer Corps) was to screen the right flank, while LII Corps, with two infantry divisions, screened the left.

On the Soviet side, General Konstantin Rokossovsky’s Central Front defended the northern zone of the Kursk Salient while General Nikolai Vatutin’s Voronezh Front held the southern zone.

Knobelsdorff would be at the center of one of the deciding armored battles of the entire war. The divisions of XLVIII Panzer and II SS Corps had been out of the line since April and had undergone extensive training from the commanders down to rankers in breaching fortified defenses, antitank ditches, and antitank strongpoints, and in coordinating with the Luftwaffe.

Knobelsdorff, who had been directed by Hoth to commit the 10th Panzer Brigade with the Grossdeutschland Division at the main point of the corps’s attack, knew the new Panthers were suffering severe mechanical teething problems and doubted they would live up to Hitler’s high hopes. Still, between Grossdeutschland’s own 92 tanks (including 14 heavy Tigers) and the panzer brigade, that division on July 5 controlled nearly as many tanks as all of II SS Panzer Corps.

The stage was set for a massive confrontation. The struggle involved some 900,000 men, 2,700 tanks, and 2,500 aircraft on the German side, and 1.3 million men, 4,200 tanks, and 2,650 aircraft on the Soviet.

A Victory on July 7th

Fourth Panzer Army launched preliminary attacks on July 4 and captured observation points on both corps fronts necessary for direction of the artillery preparation the following day. Knobelsdorff’s corps battled thunderstorms as well as the Soviets and on the 5th had to cross a seemingly bottomless sea of mud along a rain-swollen and heavily mined creek under troublesome flanking fire. There was little air support, aircraft having been concentrated that day on helping II SS Panzer Corps. Knobelsdorff, as usual, was well forward, visiting first the 3rd Panzer Division, then Grossdeutschland, and then the 11th Panzer Division.

Knobelsdorff’s account says he held his panzers back until Grossdeutschland’s own panzer regiment had crossed the water obstacle. The division’s engineers simply could not build a bridge that would stay in place, and the planned mass tank attack by Grossdeutschland never did come off.

Still, Knobelsdorff broke through the first belt of Soviet defenses by 7 am, according to the Fourth Panzer Army Kriegstagebuch. He finally got all his panzers across by evening. On July 6, Grossdeutschland’s panzer regiment reported it had penetrated the second belt at one spot. Finally, thought Knobelsdorff, the route north was free! Moreover, the Panthers were finally forward and doing some fighting.

Knobelsdorff visited Grossdeutschland’s command post only to find the report was false and the division was still engaged in hard fighting in the middle of the defenses. At 9 pm, the panzer regiment—now in control of the Panthers, too—really did crack through the belt. But the Panthers were breaking down right and left.

The following day, Knobelsdorff ordered the Grossdeutschland and 11th Panzer Divisions to attack the flank of Soviet forces hitting II SS Panzer Corps from Oboyan and then to advance in close parallel to the SS Panzer Corps.

Grossdeutschland surged forward, but the 11th Panzer Division was still fighting its way free of the second belt and was under heavy air attacks. The 3rd Panzer Division on the left failed to cross the Pena because of swampy terrain and heavy enemy fire. Knobelsdorff, demonstrating his flexibility, decided to pass it forward behind Grossdeutschland.

Hoth told Knobelsdorff that he should expect a major fight with the Soviet tank reserves in the next few days. Indeed, Fourth Panzer Army’s advance provoked furious counterattacks by the First Guards Tank Army, including the II Guards and V “Stalingrad” Tank Corps, as well as by the lead elements of the fresh VI Guards Tank Corps. Air reconnaissance had failed to detect the Soviet concentration, which came as a surprise. “Thus came the panzer battle sooner than we had expected,” Fourth Panzer Army recorded.

Hoth told Knobelsdorff he intended to smash the First Tank Army from both its flanks. The aim was not merely to push the Soviet forces back, but to pin them and destroy them! Knobelsdorff got the upper hand that day and thrashed the Soviet tanks on his front, but neither corps gained noteworthy ground.

Grossdeutschland, which had started with 300 panzers, now had only 80 combat capable, in large part because the Panthers were clogging the maintenance system with breakdowns. “It is to be hoped,” recorded Knobelsdorff’s operations chief, ”that tomorrow’s envelopment succeeds, that after the annihilation of his panzer forces we push forward again, and that he has no stronger reserves north of the Psel.”

General Friedrich Fangohr, Fourth Panzer Army’s chief of staff, later recalled, “7 July marked a complete victory for General Knobelsdorff’s men. They had not only routed Soviet tank forces in a meeting engagement but—more critical from the overall perspective of the offensive—had succeeded in slogging their way close enough to Oboyan to bring the Psel River crossing, the last major barrier before Kursk, under artillery fire.”

Holding Back the Soviets

Hoth’s planned double envelopment of the Soviet tank forces on the 8th did not succeed. The XLVIII Panzer Corps left flank was open and vulnerable, and when word reached Knobelsdorff that the main body of Soviet tanks was about to attack him from the north and northeast, Grossdeutschland and the 11th Panzer Division had to stop and throw out defensive screens. The corps held its line, just barely, under the combined assault of VI Guards Tank and III Mechanized Corps.

The II SS Panzer Corps maneuver to hit the Soviet left flank with the 1st and 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Divisions pushed even more Soviet forces against Knobelsdorff’s front, but his divisions were able to destroy them. The II SS Panzer Corps claimed it had destroyed some 250 Soviet tanks because they attacked in penny packets, which allowed the Germans to engage in mobile defense. Fourth Panzer Army reckoned actual tank kills as 95 opposite XLVIII Panzer Corps and 100 opposite II SS Panzer Corps.

Soviet resistance suddenly eased on the 9th, and air reconnaissance and reports from ground troops indicated the Soviets were falling back to the north. Knobelsdorff’s troops, finally supported again by the Luftwaffe, rolled ahead, and the panzer corps estimated that Grossdeutschland that day destroyed 66 enemy tanks and the 11th Panzer Division 35 at virtually no cost to themselves. The lead battalion of II SS Panzer Corps’s Totenkopf Division cleared the last bunkers south of the Psel and forded the river. But Fourth Panzer Army was only halfway to Kursk.

On July 10, II SS Panzer Corps readied to attack Soviet forces at Prokhorovka, while XLVIII Panzer Corps fought to clear a bend west of the Psel River. Constant tank battles raged during the day on Knobelsdorff’s front, and the panzers won every engagement. Grossdeutschland alone claimed to have destroyed 49 Soviet tanks. Hausser’s II SS Panzer Corps also fought large Soviet forces near Prokhorovka, which relieved some of the pressure on Knobelsdorff’s flank.

Manstein met with Kempf and Hoth on the 11th and asked their advice on whether to discontinue the attack in light of Ninth Army’s halt on the 9th of its attack on the north face of the salient. Kempf wanted to stop, but Hoth wanted to continue to the Psel River along its length and destroy as many Soviet divisions on the south bank as possible. Manstein ultimately agreed with Hoth.

That day, Totenkopf tried but failed to expand its bridgehead across the Psel River, while Knobelsdorff’s corps fought off more powerful counterattacks—the X Tank Corps had appeared on its front—and encircled and destroyed 100 Soviet tanks. The Fifth Guards Tank Army, the strategic Soviet tank reserve in the south, arrived at Prokhorovka, and a huge battle with the SS erupted there.

The Soviet attacks were so strong on July 12 and 13 that Fourth Panzer Army, assessing that it was hit by at least parts of nine tank and mechanized corps as well as multiple rifle divisions, could barely hold its own. Knobelsdorff, on his front, aggressively followed up each withdrawal of repulsed Soviet tank forces to strengthen his defensive positions, but he had to direct the weight of Grossdeutschland and the 3rd Panzer Division to the west rather than the north to deal with a Soviet breakthrough in the zone of the 332nd Infantry Division, which had taken charge of the corps’ flank security.

The drive northward had, in effect, stopped. Rain slowed movement everywhere, and Hoth worried that he would not be able to restore momentum. But the tank attacks from the northeast had been replaced by infantry attacks, and it seemed possible that the enemy had pulled back his armored reserve.

Trading Operation Citadel For the Defense of Italy

According to Manstein, Hitler summoned Manstein and Kluge to his headquarters on the 13th and told them that the Allies had landed in Sicily, the Italians were not fighting, and the island was likely to be lost. Because the next step would probably be an invasion of Italy or the Balkans, the Führer had decided to stop Operation Citadel in order to transfer divisions from the Eastern Front to strengthen his armies in those areas. Kluge said Ninth Army was stuck and supported abandoning the effort. Manstein argued that the issue in Fourth Panzer Army’s zone was still open and that to stop was to throw away a victory.

On the 14th, Hoth did reclaim the initiative, and Knobelsdorff’s left wing seized high ground overlooking the Psel west of Oboyan. The XLVIII Panzer Corps now faced human waves of infantry, which mortars and corps artillery mowed down. German losses were light, and morale in the corps was high.

The next day, the 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Division punched through Soviet defenses and found freedom to maneuver. Army Detachment Kempf finally linked up with II SS Corps and enveloped the Soviet forces that had stood between them. It appeared that Soviet resistance had been smashed, and Fourth Panzer Army was believed to be on the brink of a major victory.

But the situation in Army Group Center, struck from the east by a Soviet counteroffensive, had continued to deteriorate, forcing a decision to break off Army Group South’s attack to transfer forces to the north. Fourth Panzer Army received word that it was to halt offensive operations northward on the 15th. The Soviets on the 17th added to the pressure to remove divisions from the Kursk battlefield by attacking Army Group South’s Sixth Army. Operation Citadel was over.

Knobelsdorff’s Skillful Withdrawals

Knobelsdorff, from February 26 until September 4, 1944, was transferred to command XL Panzer Corps, also labeled Gruppe von Knobelsdorff and Panzergruppe von Knobelsdorff at various times, in the Ukraine. Generalleutnant (Maj. Gen.) Hasso von Manteuffel, as it happened, had arrived in the sector just before him to take command of the Grossdeutschland Panzergrenadier Division in the neighboring XLVII Panzer Corps sector; Manteuffel and his division were subordinated to XL Panzer Corps on March 11. He would fight beside Knobelsdorff again in Lorraine against Patton as commanding general of Fifth Panzer Army.

The two panzer corps, fighting along the Bug and Dniestr Rivers, were just beginning a withdrawal movement in anticipation of a major Soviet offensive, dropping back overnight to a “B Line,” with further phased night withdrawals to follow. On March 10, after weeks of quiet, the Soviets launched a ferocious attack on the Grossdeutschland Division, part of a general offensive aimed at the Romanian oil fields, that broke through the line and was stopped only after tremendous effort by German infantry.

The Soviets aggressively followed each of the corps’ steps backward, knocking small holes in the XL Panzer Corps line with tanks and infantry, but Knobelsdorff launched counterattacks that resolved many problems and deftly executed further retreats to deal with the others.

A survey of Knobelsdorff’s orders to his officers and men in XL Panzer Corps reveal a commander with a fine sense of frontline combat. In one, he demands that units stop exaggerating the size of the enemy forces attacking them, as he says he knows his subordinates are, because he will make mistaken decisions on the basis of false information.

In another, he instructs panzer unit commanders that they are not to pull their tanks and assault guns back to rearm and refuel and leave the infantry stranded. Supplies are to be brought forward, and it is the duty of every panzer soldier to be the steadfast backstop for the infantry in attack and defense. He underlined, “That is why we are the Black Hussars,” a reference to the black panzer uniform.

In a third order, he urges his commanders to keep in mind that their troops have been in constant battle against overwhelming odds.

Knobelsdorff was decorated again for his command of the corps during its skillful withdrawal into East Prussia during August. Further, the performance appraisal for his command of the corps noted that he was a mobile combat soldier, decisive, and a “doer.” He exercised wide personal influence across the front and on all subordinates. He was firm in a crisis, unyielding, and a dedicated optimist. The only criticism was that at times he followed impulse rather than thinking through all the tactical possibilities. The commanding general of Third Panzer Army judged him suitable for command above the corps level.

Knobelsdorff vs Patton

Knobelsdorff took command of First Army in Lorraine on September 10, 1944, only five days after departing the Eastern Front. His sprawling army at this point faced the right wing of General Courtney Hodges’s U.S. First Army in Luxembourg and General George Patton’s Third Army in Lorraine. His first orders to XIII SS and XLVII Panzer Corps were to throw the Americans back across the Moselle with their reserves. This was vintage Knobelsdorff.

The panzer general battled Patton until he was relieved on November 30. Knobelsdorff had few panzers to work with, but he waged war as he had in the East, trading ground for the survival of his forces. His superiors, however, thought he traded too much territory, though he succeeded in holding Patton west of the Siegfried Line, or West Wall.

Knobelsdorff’s old comrade Balck wrote in his performance review in early December that, as First Army commanding general, Knobelsdorff had continued to be an active leader and a man of clear decisions and firm will. But, assessed Balck, the previously observed fact that he was not an outstanding tactician had shown itself during the fighting in Lorraine. Knobelsdorff, said Balck, had not come up with fresh ideas.

Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal) Gerd von Rundstedt, head of the German Army High Command on the Western Front, nailed the coffin closed: “[D]espite laudable personal enthusiasm for action, he did not fully meet the challenges that I had to put before him as commanding general of First Army, because he did not always find the improvisations necessary for waging this defensive battle. His demanding physical activities in the East may play a role.”

Knobelsdorff was relieved and did not receive another combat command through the end of the war. It was a lamentable fate for one of Germany’s truly talented operational commanders. He survived the war and died in 1966.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments