By Colonel Richard D. Camp, Jr. USMC (Ret) and Ms. Suzanne Pool

Marine Captain Frank Farrell stood in the open door of the Army Air Corps C-47 waiting for the “green light,” the signal to leap into space, on a mission that could mean life or death for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people. The tension of the mission was clearly etched in the hard lines of his tightly clenched jaw, for he and a handpicked team were parachuting into the Japanese-held city of Canton, China, to hammer out the details of the Japanese garrison’s surrender—only two days after Emperor Hirohito had capitulated.

A Vanquished And Unpredictable Foe

Having served with the lst Marine Division during the Guadalcanal and Peleliu operations and as an Office of Strategic Services (OSS) field commander, he was well aware of how fanatical the Japanese could be—would they obey and surrender or would they disobey and fight?

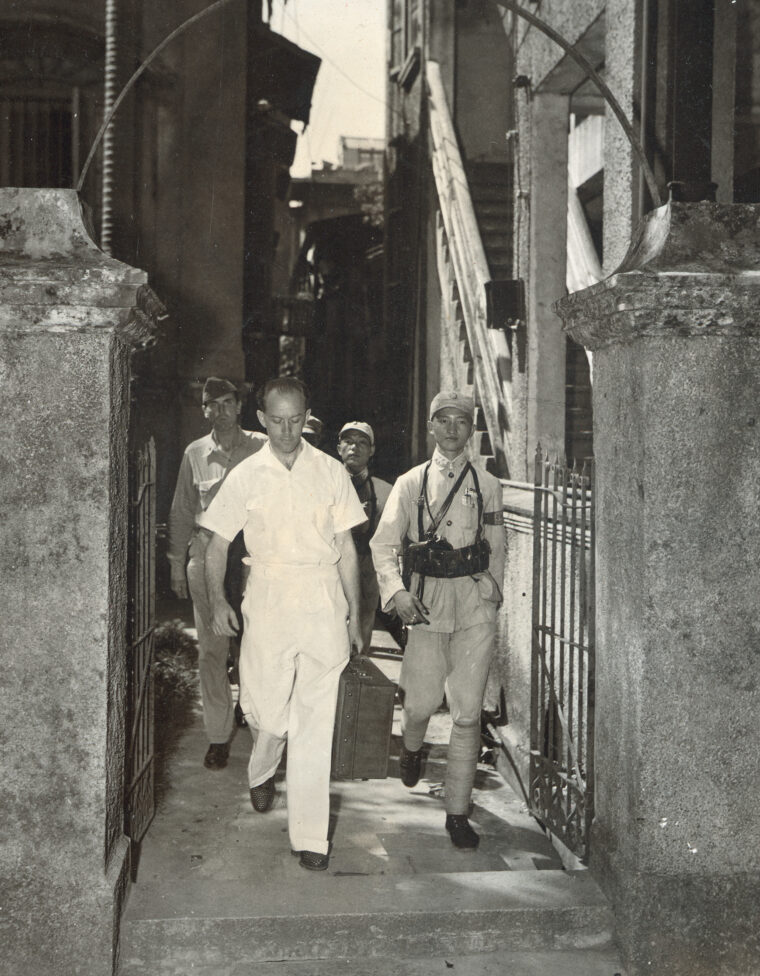

As he floated down, oscillating slightly in the parachute shroud lines, he could plainly see armed Japanese forming a reception committee. Immediately upon landing, the team was surrounded by bayonet-wielding Japanese infantrymen who obviously did not know about the surrender.

Talking fast, Farrell was able to convince their commander to take them to the Swiss Embassy, where they stayed for two days while waiting for the Japanese to sort it out. Finally able to meet the Japanese commander, Farrell was relieved to find that he was going to obey the Emperor and agree to the details of surrendering his command to General Chang Fa Kwai, Commander-in-Chief, 2nd Chinese Army Group. At the time Farrell was the officer in charge of an OSS Field Intelligence Center attached to that Chinese Army group.

Farrell did not start out as an intelligence officer, or even as a soldier. At the time of Pearl Harbor he was a 29-year-old feature editor of the New York World-Telegram. Tall and movie-star handsome, his occupation allowed him to associate with the upper crust of New York society, where he earned a reputation as a ladies man and an “up and comer.” He was outgoing and gregarious, a man who projected a hail-fellow, well-met personality. He was not a dilettante, however, for he was known for having ambition and drive, with a newsman’s tenacious quest for accuracy and completeness—getting the full story.

Physically and mentally tough, Farrell decided to leave his job for the excitement of military service. After being turned down by the Navy because of high blood pressure, he was able to convince Colonel “Wild Bill” Donovan, head of the OSS, to use his influence to get him into the Marine Corps, the quid pro quo being that Farrell would help set up a system of coast-watcher stations in the rugged Solomon Islands to glean intelligence on Japanese movements.

After six weeks of training at the Quantico Marine Base, he was commissioned and ordered to join the 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division, for the Guadalcanal campaign. His success there led to legendary Marine Lewis “Chesty” Puller calling Farrell “the finest young Marine Officer I ever knew.”

Battle-Hardened In South Pacific Jungles

Attached to the S-2 (intelligence section), Farrell led small units into the jungles gathering intelligence, becoming an adept patrol leader by surviving the deadly close encounters with the bush-wise Japanese. His mentors, including Puller, taught him well. Patrol after patrol hardened this young officer, giving him the confidence and the mental toughness to operate independently.

After Guadalcanal, Farrell took part in two more island campaigns, Cape Gloucester and Peleliu, where he was awarded a Silver Star for conspicuous gallantry.

The long arm of “Wild Bill” Donovan finally caught up with now Captain Farrell, ordering him back to the United States for training in preparation for special assignment. In May 1945 he received orders for Kunming, China, and special temporary duty with the OSS as commander of the Buick Mission, a reconnaissance of Japanese forces in the coastal areas of South China, particularly the strategically important Luichow Peninsula. The mission was so successful that Farrell was awarded a Bronze Star. With the Japanese surrender, Farrell and his team were given new orders for Canton, to arrange the Japanese surrender, rescue Allied POWs, and investigate cases of possible war crimes.

Having completed their part of the mission, Farrell’s team was about to catch a flight out of the city when they spotted a house with a large radio antenna—an obvious communication station. Curiosity aroused, he ordered his men to search the house and, to his amazement, they found evidence of a major German spy ring whose operations covered the entire Far East. This happenstance discovery led Farrell on a two-year investigation culminating in the arrest and prosecution of 21 members of the Bureau Ehrhardt, a secret intelligence agency of the German High Command, which continued to operate in violation of their May 1945 unconditional surrender.

For decades Germany had had an extensive commercial investment in China and, over the course of many years, had cultivated excellent diplomatic relations with the Chinese Nationalist Government, led by Chiang Kai-shek. There were fairly large German communities in the major port cities where they enjoyed a high standard of living. Trade was particularly encouraged by the German War Department, hoping to develop a source of scarce raw materials. The German Army even furnished advisers to train Chiang Kai-shek’s army, an arrangement that lasted until Hitler withdrew the advisers in 1938 when he was shifting his support to Japan, then at war with China.

Nazi Party Attempted To Win The Hearts And Minds Of Ex-Pats

The German government’s interests in China were represented by the Diplomatic Service whose embassy was in Nanking with branches in Shanghai and Peking. In the late 30s, the German ambassador opposed the Nazi’s pro-Japanese policy and was recalled in 1938. During the critical years that followed there was hardly any coordination of German political affairs in China.

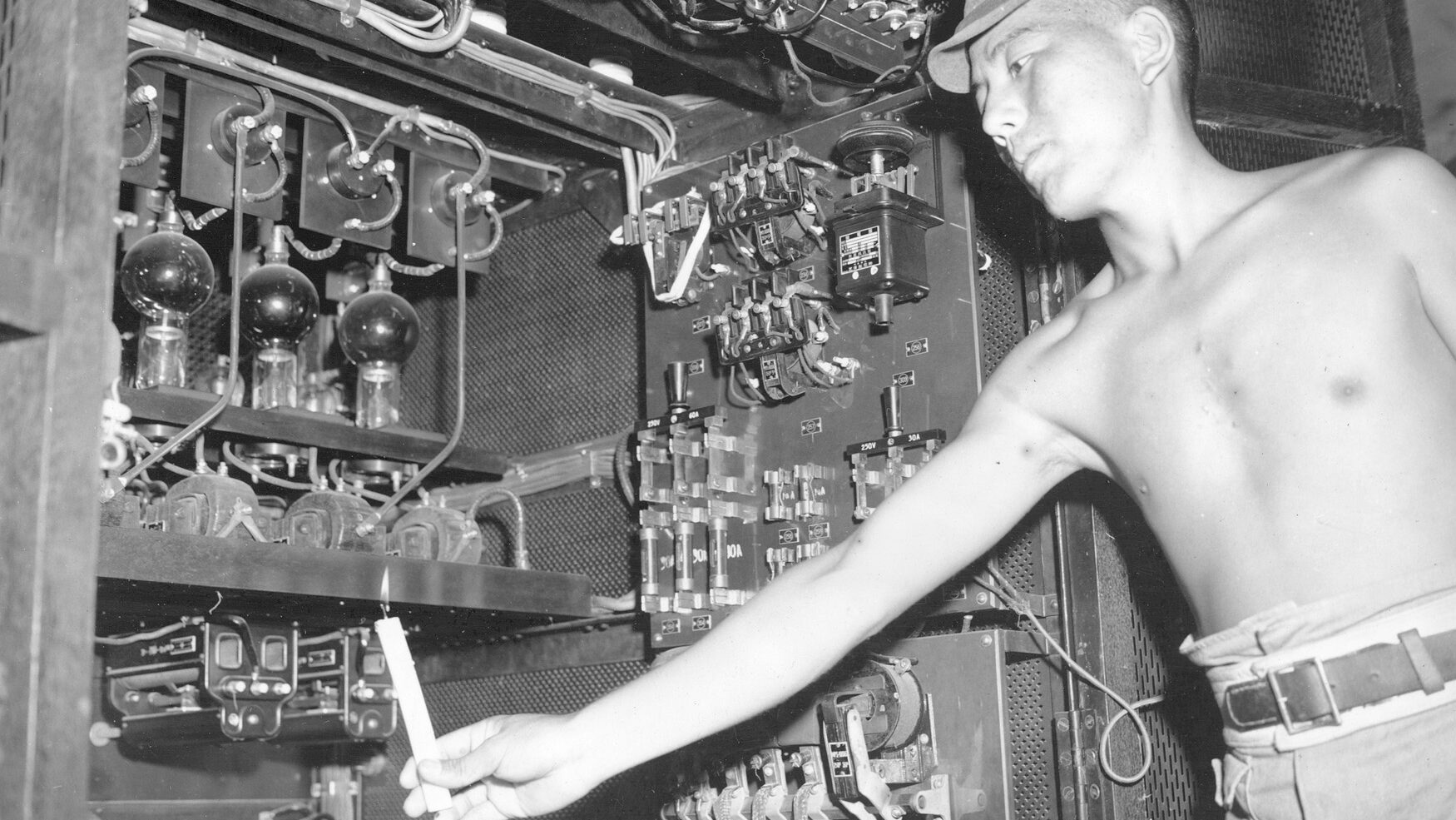

The embassy maintained a radio station (XGRS) that beamed propaganda in six languages. The embassy also supported a listening post that monitored Allied broadcasts for use by the Nazi Party’s propaganda office, as well as the War Department’s Intelligence Bureau.

The Nazi Party in China had its headquarters in Shanghai but was directly subordinate to Berlin through the National Socialist Organization for Germans in Foreign Countries (AO). AO’s principal aim was to penetrate the existing German societies abroad, to gain control over public and private institutions, and to have trusted members appointed to consular and diplomatic posts. The AO and the Foreign Office were in frequent conflict.

Tentacles Of German Intelligence Ran Deep In China

The Nazi Party exercised considerable control over all German nationals living in China. Any party member who did not obey orders was subject to disciplinary action. There was even a local Gestapo office in Shanghai, acting under the direct orders of the Gestapo Chief of the Far East, Colonel Joseph Meisinger, the “Butcher of the Warsaw Ghetto.”

The Nazi Party also oversaw, in Shanghai, satellites of the Storm Troopers (SA), German Labor Front (DAF), League of German Girls (BDM), and the Hitler Youth (Hitler Jugend) organizations. There was even an offshoot of Goebbels’ Propaganda Ministry, operating under the cover name “German Bureau of Information (DISS),” under Baron Jesco von Puttkammer, an ardent Nazi and member of the German upper class. His Shanghai Park Hotel office became the focal point for propaganda in the Far East, even penetrating into North and South America and Europe.

The most important German organization to penetrate China was the Intelligence Department of the German War Office, the Kriegorganization or KO. Its mission was to gather military and economic intelligence through the use of agents acting under the guise of journalists, doctors, technicians, diplomats, and businessmen. Organized in 1940, its first leader, Navy Captain Louis Theodor Siefken, recruited agents from the German community, relying on their connections to expand operations throughout China and the Far East.

The principal agents were German but there were also subagents of various nationalities—Chinese, Japanese, Russian, French, Portuguese, Italian—involved in the spy network. The head of the organization worked out of the embassy office in Shanghai, providing diplomatic “cover” for him, but raising the hackles of the “official” foreign-service types. Siefken used the embassy radio transmitter to send reports to Berlin, causing additional friction because he used his own code which was undecipherable by the diplomats.

The KO also established listening posts to monitor Allied broadcasts. It broke one of the U.S. Coast Guard’s codes, enabling it to identify ships’ locations for German submarines.

In the autumn of 1942, the Abwehr (German military intelligence) replaced Siefken with Lt. Col. Lother Eisentraeger, alias Count Schwerin, alias Colonel Ludwig Ehrhardt, a secretive professional spy master. Ludwig Ehrhardt was a dedicated Nazi with a great deal of field experience, having successfully led “Fifth Column” agents in the Balkans. As an officer in World War I, he was wounded several times. These strong army ties stood him in good stead when, in the late 30s, he was “sprung” from a concentration camp where he had been incarcerated for unspecified activities.

Ehrhardt Expands His Chinese Empire

Ambitious, arrogant, and jealous of rivals, he was directly involved in getting his boss, Siefken, sacked on trumped-up charges of being homosexual. Pompous, his inflated ego brought him into conflict with the consular staff in Shanghai even though he was officially accredited as one of their number.

The 60-year-old Ehrhardt was a somewhat nondescript, balding man with a high widow’s peak, prominent chin, and stern countenance, leaving one with the impression of firm authority. An extrovert, he enjoyed “the good life” and the companionship of anyone willing to keep him company and listen to his boasts.

He established a primary headquarters in Shanghai, known as Bureau Ehrhardt, with branches in Peking (Bureau Fuellkrug) and Canton (Bureau Heise)—named after their leaders, Siegfried Fuellkrug and Ehrich Heise. Under his leadership the organization flourished, recruiting agents, expanding operations, and developing sources within the Japanese military hierarchy.

Bureau Ehrhardt Ignores Orders To Cease Operations

By 1945, however, the German military situation at home was desperate. Bureau Ehrhardt clearly understood that its situation was precarious and, after repeated requests for instructions went unanswered, started burning its files in late April.

On May 8, Bureau Ehrhardt learned from foreign radio broadcasts that the German High Command had unconditionally surrendered, issuing orders to all forces under German control to cease active operations, or otherwise be subject to punishment.

But Bureau Ehrhardt did not cease operations as ordered, preferring instead to continue its espionage activities for the Japanese, still at war with the Allies. On May 12, Ehrhardt sent a message to his branch organizations ordering them to destroy their files, turn over all technical equipment to the Japanese but assist them in running it, and start a new bookkeeping system effective May 12, destroying the old ones. He also “suggested” that they fully cooperate with the Japanese—tantamount to an order.

The Japanese did not take over the stations because all members of the staff continued working, including the radio-intercept operator in Canton. This was the radio station discovered by Farrell’s group and led to the eventual uncovering of the entire Ehrhardt organization.

After stumbling onto the radio transmission site and evidence of German espionage, Farrell reported his findings to the Chinese. They then appointed him a member of the War Crimes Investigation Board of Chiang Kai-shek’s Military Council, Canton Branch.

Farrell realized that he had to act quickly because time was not on his side as he had evidence that key suspects—Ehrhardt, Meisinger, von Puttkammer, and others—were “going to ground,” in an effort to escape Allied counter-espionage efforts. Key witnesses, many of whom were former Japanese intelligence operatives returning to Japan, were also in danger of being lost in the confusion of war-torn China.

So, armed with the authority of the Military Council, Farrell used the extensive resources of the OSS Counter-Espionage Section (X-2 Branch) to assist in locating, interrogating and, in some cases, accompanying Chinese police to arrest suspected war criminals. As he and his team identified suspects and evidence of illegal activities beyond the Canton-Shanghai area, other Strategic Services Unit (SSU) Field Detachments throughout the Far East were tasked to provide support. Their investigations uncovered evidence of the execution of American flyers, the mistreatment of Allied POWs, the collaboration of Americans and other foreign nationals, as well as the postsurrender activities of the Bureau Ehrhardt.

Captured Japanese Rat Out Bureau Ehrhardt

Farrell quickly discovered that his investigation could be compared to peeling an onion—each layer exposing another, adding to his store of information on the core of German subversive activities. The interrogation of the two German radio operators revealed Ehrich Heise as the head of the Canton organization. After being confronted with irrefutable evidence of postsurrender espionage, Heise provided a chart of the German organizational structure in China, implicating Ehrhardt as the head of the KO. The testimony of Maj. Gen. Tomita Naosuka, Chief of Staff of the Japanese 23rd Army, and Shaw Dja-Moo, the Heise Chinese interpreter, proved to be the most damning, because both stated that the Heise organization continued providing intelligence after the German surrender.

Heise, bald and overweight, who was said to bear a resemblance to Goring, finally admitted that his organization continued its espionage activities, at the “suggestion” of Ehrhardt, until Japan surrendered. As a result of his testimony, Farrell jailed Heise, the local Nazi Party leader, and all members of the Consulate, who were stripped of their diplomatic immunity.

While tracking several of these agents, Farrell was ambushed near his hotel one night by an assassin who fired one shot at a distance of 10 feet, just missing, but so close that Farrell told of feeling the round pass his head. The flash from the gun blinded him, so he was unable to return fire or get a good look at his assailant.

Not long after this attempted murder, an intruder broke into his hotel room, but was scared off by Farrell and another member of his team who brandished .45 caliber pistols. The two attacks convinced Farrell that he was on the right track.

The Heise investigation also uncovered the espionage activities of the four members of the Bureau Fuellkrug in Peking, which had continued to send intelligence information to the Japanese North China Army after the German surrender. Farrell had the four chief operatives quickly rounded up by Chinese police and jailed.

Having rolled up the Canton and Peking branches of the Kriegsorganization, Farrell and his team moved their base of operations to Shanghai in an effort to prove their case against Ehrhardt and bring him and his cohorts to justice. Using the Heise organizational chart, they scoured the Shanghai area, netting operatives. A few of the Bureau Ehrhardt were willing to testify against their former boss to gain clemency from prosecution.

Witnesses Emerge With Damning Testimony

But others stonewalled, refusing to admit any complicity in postsurrender espionage. Hans Dethleffs, a Bureau member, swore, “I know that we stopped here [Shanghai] completely; with the day of the German collapse; we did not work anymore.” Another, Rudloff, stated: “I have sworn on the Gospel before Captain Farrell that to the best of my knowledge nobody of the Bureau Ehrhardt worked for the Japanese after the German surrender.” Heinz Peerschke said he “simply studied languages after the surrender.” Farrell, a hard-nosed skeptic, refused to believe their stories and had them arrested.

Farrell found that those who had been persecuted by the Nazis, particularly Shanghai’s Jews, were more than happy to testify, getting even and gaining a little retribution for past injustices. Included in this category were several diplomats who had an axe to grind because of past mistreatment. Captain Louis Siefken, whom Ehrhardt had discredited and replaced, was one of the first to testify, no doubt gloating over this strange twist of fate. A third group, who were simply innocent Germans, were desperately trying to get on with their lives.

Expanding his search, Farrell hauled in former Japanese intelligence officers who offered damning evidence against Ehrhardt and the Kriegsorganization. Lieutenant Colonel Akira Mori, the senior Japanese intelligence officer in Shanghai, was told by Ehrhardt after the German surrender that “he would continue to help them.” Mori said the Japanese High Command was particularly anxious for the Ehrhardt Bureau to continue its efforts because it was providing important tactical information on U.S. Navy operations during the battle for Okinawa.

A staff officer in the 23rd Army, Kobayshi Kazuo, remembered a telegram in late May, 1945 from Shanghai stating that the Ehrhardt office would continue working with the Japanese, and that Ehrhardt was paid twice, once in gold. Kazuo also recalled a report from Heise to him stating that the Chinese were holding back against the Japanese, hoarding their most capable troops and equipment for the “future unification of China.” It was a clear indication that Chiang Kai-shek was preparing for the fight against the Communists under Mao Tse-tung.

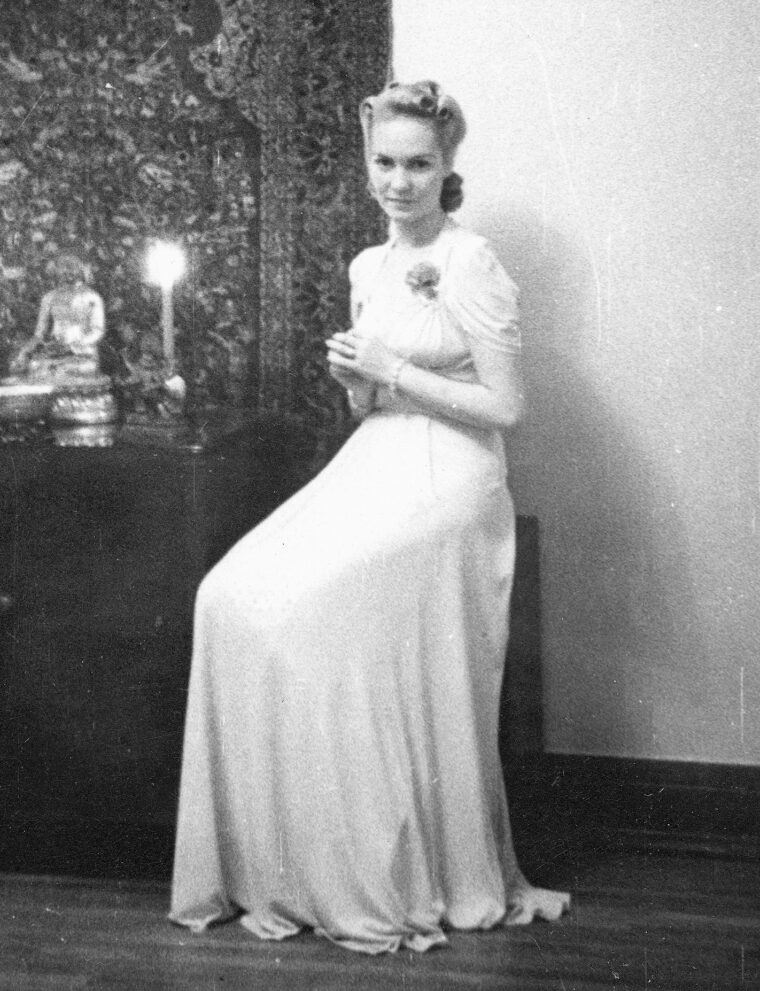

The Japanese Foreign Affairs Section of the 23rd Army also outlined its use of agents and spies—two of whom Farrell personally tracked down to gather intelligence. One, Tam Ping Kuo, alias Bianca Tam, alias Bianca Sannino, he compared to Mata Hari, the notorious international spy of World War I. She was arrested for being a Japanese spy, collaborator, extortionist, perjurer, prostitute, and procuress. Tam, an Italian and the daughter of a highly respected naval family, married a Chinese officer and, after the war started, left him for the life of a Japanese agent. During the war Tam lived with several men, including the Vichy French Consul in Canton, who was a notorious Japanese collaborator. Tam ended her relationships when the men either ran out of money or information. When the war ended, she tried to entice American officers with sexual favors to fly her out of China but instead ended up in a Chinese stockade. The other, Rosaline Wong, was convicted by a Chinese court of the same offenses and executed.

Satisfied that he had enough evidence for conviction, Farrell swore out a warrant and, accompanied by Chinese Army Officers, arrested Ehrhardt and eight confederates. The arrest went without incident, almost a letdown considering the power these men had wielded during the heyday of the Third Reich. Von Puttkammer’s arrest quickly followed, the Baron loudly proclaiming his innocence to one and all. The last, Meisinger, publicly posturing for his fellow Nazis with the classic “they’ll never take me alive” speech, meekly submitted when confronted with the aggressiveness of Farrell.

Justice, Medals And Farrell’s Return To His Pre-War Career

In August 1946, the United States Military Commission in Shanghai brought the men to trial. In all, 27 Germans were prosecuted and 21 convicted as a result of Farrell’s investigation. Ehrhardt was sentenced to life imprisonment, von Puttkammer to 30 years at hard labor and the remainder, except Meisinger, received terms from five to 20 years. Meisinger, the “Butcher of the Warsaw Ghetto,” was turned over the Polish government, found guilty of crimes against humanity, and executed.

For this exceptionally meritorious service, Farrell was awarded a Legion of Merit, normally awarded to those of very senior rank. He was also awarded the Breast Order of the Cloud and Banner, Seventh Grade, one of China’s highest military decorations.

On March 5, 1947 Captain Frank Farrell received orders to demobilize and return home, having carried out one of the most demanding independent assignments of any officer of his rank and experience in the annals of the Corps. Operating independently for two years, he almost single-handedly broke up and brought to trial a major enemy spy ring. He interrogated more than a thousand witnesses and examined an even greater number of documents in various foreign languages, literally covering most of the 5,000 Germans in China.

Arriving home, he picked up where he left off, going on to become a celebrity in his own right as a columnist with the New York World Telegram, a talk show host, and a colonel in the Marine Corps Reserves.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments