By Don Smith

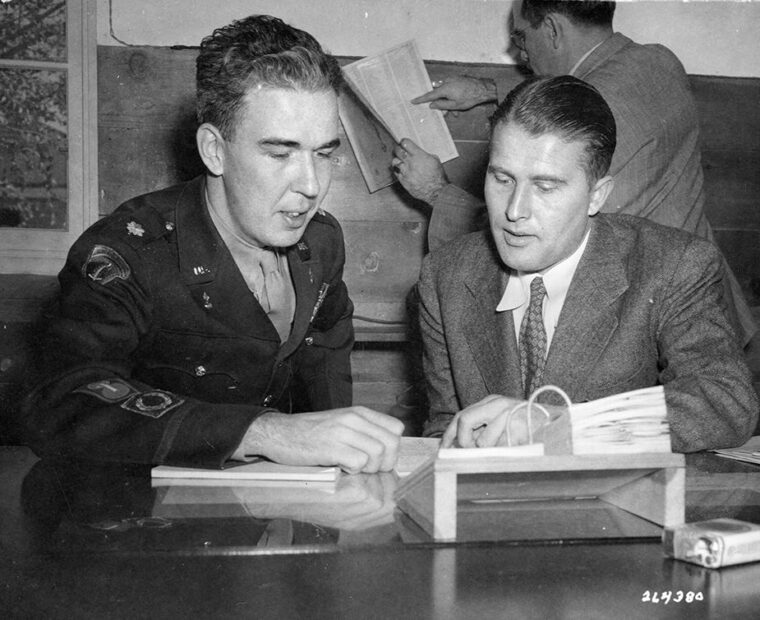

At first, Major Robert Staver seemed to have plenty of time. An Army Ordnance officer with a mechanical engineering degree from Stanford, he had been sent to Germany as part of the Combined Intelligence Objectives Subcommittee. The CIOS was a British-American organization tasked to search for and exploit scientific and technical targets in defeated Germany. Staver’s specialty was rocketry, and in May 1945 he hit paydirt. Operation Paperclip—the American effort to bring German scientists and technicians to the U.S.— began two months later in cooperation with the hunt for components of the V2 ballistic missile, one of Hitler’s terror weapons.

Staver and other American investigators had reached Nordhausen, a town in the central German state of Thuringia. Nordhausen was home to the primary V2 rocket production facility; Staver was looking for the scientists and technicians who built the rockets. Most had scattered into the surrounding towns or other parts of Germany. But American troops had firm control of their occupation areas and the Nazi armies were long gone. It seemed only a matter of time before Staver and his fellow investigators from CIOS and other technical search teams would ferret out their targets and round them up—until politics intervened.

Negotiations between American, British, and Soviet leaders led the United States to decide to withdraw its troops from large sections of central Germany. As these areas contained many key Nazi scientific and technical facilities, Staver and his colleagues now had just a few weeks to finish their work. This led to a frantic, sometimes haphazard rush to find and secure as many German technical assets as possible before the U.S. Army pulled back.

The American armies’ push into central and eastern Germany had exceeded expectations. U.S. forces advanced far into Thuringia and the neighboring state of Saxony—both of which were part of the Soviet occupation zone. Army historian Earl Ziemke estimated that when the war ended American troops held over 16,000 square miles of territory that had officially been allocated to Russia. One-third of the area American troops had conquered would have to be relinquished.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had other ideas. After Germany had surrendered in two separate ceremonies—to the U.S. and U.K. on May 7 and to Russia on May 8—Churchill had become convinced that the Soviets would be untrustworthy postwar partners. At the Yalta Conference in February, Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin had said the Soviets would allow Eastern European countries to elect new governments through fair and democratic elections.

By early May, it was clear that democrats in Poland and other Soviet zone countries were under pressure from Soviet-sponsored Communists. Churchill felt the Americans and British needed leverage against Stalin. The Soviet zone territory then in British and American hands could provide that leverage.

“Churchill felt strongly that the Americans should display no undue haste in withdrawing from the heart of Germany,” wrote James McGovern in Crossbow and Overcast, his 1964 account of the American search for Nazi scientists and technology. Instead, the Americans “should delay their departure at least until the Potsdam Conference in July, when some troublesome problems that had arisen with the Soviet Union could be settled.”

General Dwight Eisenhower, supreme commander of Allied troops in Europe and President Harry Truman disagreed. Robert Murphy, a U.S. State Department official, served as Eisenhower’s political advisor. In September 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had told Murphy that he “regarded Germany as the testing ground for Soviet-American cooperation.” Ike “was determined to do nothing which might increase Russian distrust” of the West, which was intense. In the summer of 1945, Eisenhower and Truman not only wanted Russian cooperation—they needed it.

U.S. leaders expected a long, costly fight to defeat Japan. At Yalta, FDR told Churchill and Stalin that Japan might not be conquered until 1947. The Americans desperately wanted the USSR to wholeheartedly and forcefully join that fight. They also hoped the fledgling United Nations could develop into a potent force that could prevent future world wars. If the Soviets declined to use their military and diplomatic power to support the UN, it would fail. Eisenhower, said Murphy, “chose to politely disregard Churchill.” The Soviets refused to let American and British occupation forces enter Berlin until they first committed to leave Soviet zone territories. Truman consented and agreed that American and British forces would retire to their own zones by July 1, 1945.

The decision wasn’t a total surprise to the American investigators in Germany. McGovern’s Crossbow and Overcast notes that Colonel Holger Toftoy, chief of the U.S. Army Ordnance Branch Technical Intelligence Division in Europe, had known by late April that the V2 plant at Nordhausen and many other prized Nazi technical sites in Americans hands were actually inside the Soviet Occupation Zone.

“Given the fact of American control” of those facilities and their surrounding areas, though, Toftoy initially felt his teams would have enough time to analyze and exploit the Nordhausen site “in orderly fashion.” In May, though, Toftoy and CIOS and all the other American technical investigators were warned that the Russians wanted to fully occupy their zone by June 1, later extended to July 1.

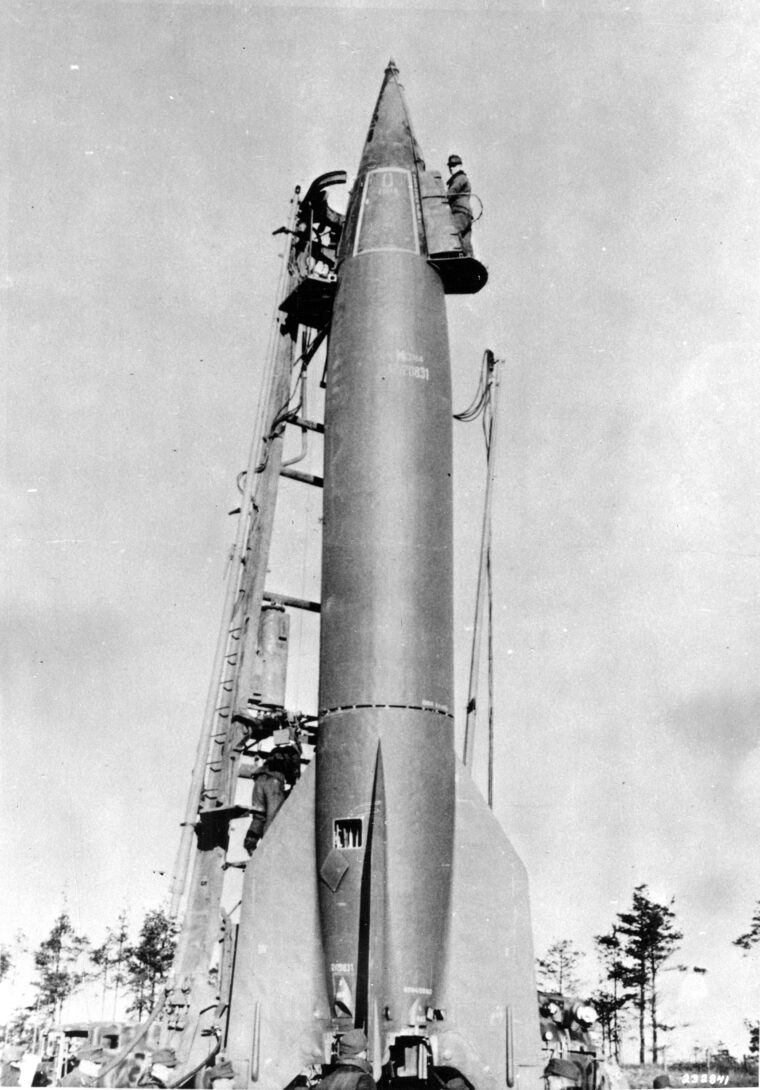

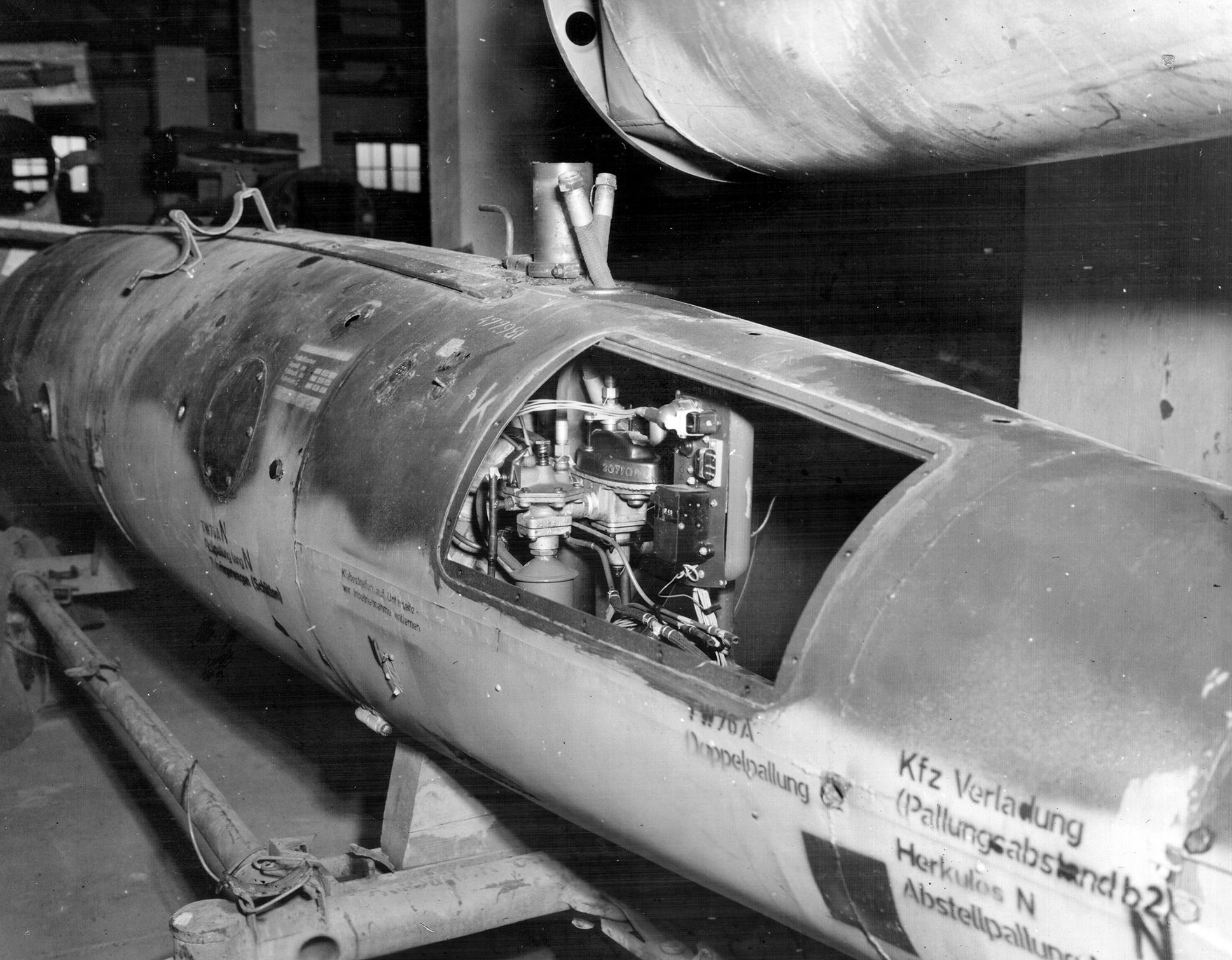

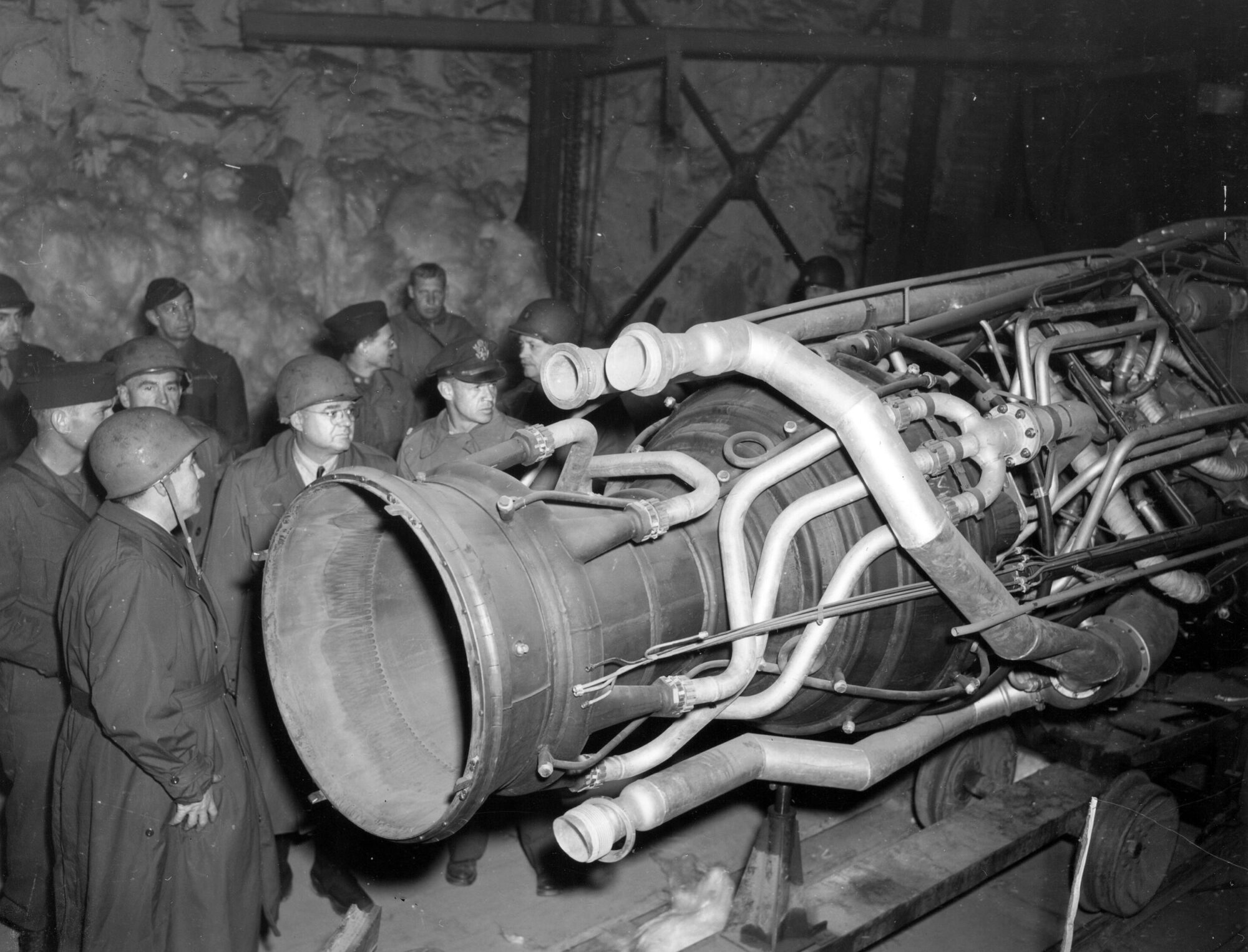

In May, much of the real work to find and analyze Nazi technologies was just beginning. One of Colonel Toftoy’s subordinates, Major James Hamill, led V2 exploitation operations at Nordhausen. A graduate of Fordham University with a degree in physics, Hamill’s task was to ship 100 V2s (or as many as possible) to the U.S. Unfortunately for him, wrote McGovern, the Nazis had not left “completely assembled rockets…conveniently available for shipment.” Instead, V2 pieces were scattered throughout the Nordhausen facility. When the Germans retreated, newly-freed concentration camp prisoners who had worked as slave laborers in the rocket factories “destroyed many priceless rocket components and machine tools.”

POWs and locals looted the site before the Americans arrived. The Americans had no list of V2 parts. On May 8, 1945, the day of Nazi Germany’s final surrender, the “V2 technical documents had not been discovered, and not one leading German rocket specialist, who could have been used as a guide to the selection of parts required for [reassembling] an engineering device of awesome complexity had been found in the Nordhausen area.”

The looming July 1 deadline was complicated by another directive, signed in Berlin on June 5 by all the Allied powers. It ordered that “all [Nazi] factories, plants, shops, research institutions, laboratories,” equipment and documents were to be preserved and left for the Allied power who owned the zone where the items were found. This order, if followed, meant that Toftoy and his colleagues would have to leave their newly-found treasures to the Russians.

American technicians across Germany disregarded the order. The treasures were simply too good to give up. CIOS and other technical investigation teams had confirmed what many American military and scientific leaders suspected: the Germans were years, even decades ahead of most countries in many technical fields. “The Germans were ahead of us, in some instances from two to fifteen years” said U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF) Chief of Staff Henry “Hap” Arnold, “in the fields of rockets and guided missiles, jet engines, jet-propelled aircraft, synthetic fuels and supersonics.”

As American troops entered Germany, “Wind tunnels of incredibly large dimensions were discovered with simulation characteristics American scientists could only dream of,” wrote retired U.S. Air Force colonel Wolfgang Samuel in American Raiders, an account of the USAAF’s hunt for Luftwaffe technologies and their inventors.

In 1945, American airframe designers were pursuing jet aircraft designs that used traditional straight wings. But the Messerschmitt Me-262 and other German jets had swept wings. When American investigators captured German aeronautical research specialists, they learned that the Germans had discovered that swept wings reduced air turbulence for planes flying at faster speeds. Other German scientists had deduced how to photograph the airstreams around wing edges and surfaces, making it easier to study and measure airflows. The Germans had learned how to weld plastics, developed ribbon parachutes to use as landing brakes for aircraft, built a prototype helicopter that powered its main rotor with jets on the rotor tips (which eliminated the need for a tail stabilizing rotor). The list of Nazi technological breakthroughs went on and on.

In a June 9 memo “Disposition of Secret Weapon Installations and Armament Factories in Ultimate Russian Zone of Occupation,” the American-British Combined Chiefs of Staff determined it was “undesirable that any equipment of vital importance…should be left behind in the Russian zone.” This was counter to the terms of the June 5 declaration, which said that Nazi technical facilities and their contents were to be left undisturbed. But the U.S. wasn’t about to let other countries just have all those treasures. They also feared that, if the Soviet Union turned out to be a future foe instead of a friend, the Russians would use these technologies against Western militaries.

American technicians started to gather up, crate, and cart away whatever they could. Army Major Hamill told McGovern that Colonel Toftoy instructed him “that officially nothing was supposed to be removed from the Russian Zone. ‘But unofficially,’ Tofoty told Hamill, ‘I’m telling you to make sure that those V2s [are sent from Nordhausen into the American Zone]. Remove all the material you can, without making it too obvious that we’ve looted the place.’”

The Nordhausen V2 factory was housed in two huge tunnels bored into a mountainside. They were filled with V2 components and subassemblies, which Hamill’s team now had to extract, inspect, label for reassembly, and ship. Hamill hired former slave laborers who had worked on the rockets to assist teams of U.S. soldiers.

“The enlisted men,” wrote McGovern, “quickly learned how to recognize parts and sections of the unfamiliar V2.” The “small and intricate control devices which had guided V2s” had been manufactured in villages around Nordhausen. When the Americans arrived, German technicians hid the devices “in nearby barns, schools and beer halls. The Americans had to organize scouting parties which searched the area around Nordhausen for a radius of thirty miles before the control systems, without which the V2 would be almost useless, were located.”

Hamill’s team assembled enough rocket subassemblies and support components for 100 V2s, which he planned to ship to the port at Antwerp on captured German railcars. Then he heard Army Transportation Corps teams were en route to Nordhausen to divert the cars to other uses. Hamill had no written orders authorizing him to use the railcars, because, officially, he wasn’t supposed to be removing any equipment!

Fortunately for Hamill, one night someone sabotaged the railroad near Nordhausen with dynamite. McGovern speculates that one of Hamill’s subordinates knew of his dilemma, put two and two together, and chose to exercise some initiative. This froze the railcars in place and gave Hamill time to convince the Transportation Corps to relent. He also convinced Army engineers to build extra rail spurs connecting the V2 works to the local railhead. On May 22, the first train left Nordhausen for Antwerp. Hamill sent nine trains in total, with an average of 40 cars per train. The last train left Nordhausen at 9:30 p.m. on May 31, just hours before the expected arrival of Russian troops. Eventually more than 400 tons of sensitive rocket technology reached Antwerp en route to New Mexico’s White Sands Missile Range and other facilities in the U.S.

The USAAF investigators who found the large wind tunnels and the Germans who’d pioneered swept-wing technology had zonal border problems of their own, but not with the Russians. After the war ended, American and British officials agreed to several adjustments in the borders between their zones for a variety of reasons. Also, some American forces had advanced into portions of the British Occupation Zone and stayed there after Germany surrendered. Now the time had come for all Allied Powers to retire to their official zones.

The Hermann Göring Research Institute at Völkenrode, west of Braunschweig, was one of the American-held facilities in the British zone. It was a “scientific gold mine,” wrote Samuel. He quotes Dr. Theodore von Karman, General Arnold’s scientific advisor, who visited Völkenrode and assessed its value. Karman reported that “probably 75 to 90 percent of the technical aeronautical information in Germany was available at this establishment…the information on jet engine developments available at this establishment would expedite the United States development by approximately six to nine months.”

USAAF Colonel Donald Putt directed American exploitation efforts at Volkenrode; he decided to spirit as much equipment out of the facility as he could before the British took over. He acquired the services of one B-24 bomber and one B-17 bomber and started a nighttime mini-airlift. “The trick was to get whatever test equipment and documentation [we could] out of the place without the British noticing,” Putt recalled in an interview for Samuel’s book. British technicians had visited Völkenrode, and the British knew the site was valuable. “As soon as everyone was in bed and the lights were out, we would spring into action. There was an airfield just across town, and with trucks we’d haul this stuff over there, and quickly load it on my B-17 or B-24. By the time people woke up the next morning, they were in Lakenheath or Ireland…This went on for some time until the British caught on. At the Potsdam Conference [in mid-July] the British threw this up to General Arnold. I’m sure he must have pleaded ignorance.”

Another American officer, Major Robert Staver, also had the British on his heels. Staver was still in the Nordhausen area in early May looking for key V2 technicians. On April 3, one week before the U.S. Ninth Army arrived, the Nazis had moved V2 program lead Werner von Braun and hundreds of his key personnel to Bavaria for safekeeping. Von Braun realized the Third Reich was finished, and he wanted to continue his rocketry research postwar, presumably with American or British support. He tasked two of his engineers to collect the most important V2 technical documents and hide them. The engineers found an abandoned mine, filled some of its chambers with crates containing, as McGovern described them, “papers [that] represented thirteen years of research work and the complete plans” for the V2, and sealed the mine entrance with dynamite. The engineers then joined von Braun and his team in Bavaria, but not before telling the general location of the mine to Karl Otto Fleischer, a manager at the Nordhausen factory.

Fleischer did not go to Bavaria. He stayed in the Nordhausen region, and by mid-May Staver had found him. By then von Braun was in U.S. custody and American investigators who had questioned him tipped Staver that Fleischer might know the general location of the documents cache. Fleischer hadn’t volunteered this information, so Staver tried to trick him. He confronted Fleischer and told him that von Braun, now in U.S. custody, had said that Fleischer knew where the documents were and he (Fleischer) could help the Americans find them. Von Braun had said no such thing, but Fleischer didn’t know that.

The ruse worked. Fleischer agreed to search for the hiding place. On May 21, Fleischer found the mine near the town of Dörnten. Staver had his documents, but now he had another problem. Because of the American-British zonal border adjustments, Dörnten would become part of the British zone in just six days.

Staver needed Army Ordnance headquarters to dispatch enough trucks to haul away the 14 tons of documents. Army Ordnance headquarters was in Paris, and there were no reliable communications between Paris and Nordhausen. Staver convinced a P-47 Thunderbolt pilot who was flying to Paris to bring him along as a passenger, wedged into a small space behind the pilot’s seat. Staver got the authorization for his trucks, returned to Nordhausen, and found that British survey teams had been scouting the mine. Staver had detailed a team of Germans, supervised by an Army Ordnance officer, to clear away the debris blocking the mine entrance. When the British appeared, the American officer, who was dressed as a workman, pretended to be German. Fleischer told the British they were geologists looking for ore samples. The British eventually left, but Staver was concerned enough to accelerate the pace of activity at the mine. The shafts were cleared, and Staver’s team found all the documents and loaded them on trucks. The trucks drove away from Dörnten early on the day the British took control of the area.

The Americans left lots of technology for the Russians and British. Many of the test facilities and production works were too large to dismantle and remove. But the efforts of Staver, Hamill, Putt and other American technicians did have an impact. Boris Chertok, a key figure in creating Russia’s space program, served on a Soviet technology exploitation team (similar to CIOS) during the war. He was part of the Russian contingent that finally occupied Nordhausen.

In his memoirs, Chertok recalled “out of all the tail and middle sections, tanks, instrument compartments and nose sections [we found] we could assemble at least 15, and maybe even 20, missile bodies. But the situation was a lot worse with the innards. We did not have a single control system instrument that we could use. There were also no engines and no turbopump assemblies that we could clear for installation” into the reassembled rockets.

The Soviets had to recruit German technicians to recreate many of the V2’s critical components. In contrast, when the Americans brought Von Braun and much of his team to the U.S., they were able to work with the V2 parts and support assemblies Hamill had spirited out of Nordhausen, as well as the technical documents Staver found. The German rockets and the German scientists who built them helped the U.S. create its ballistic missile program and then its space program. The high-tech scavenger hunt had paid off for the Americans, yielding technologies and technicians that would be instrumental in the looming Cold War.

Don Smith is a retired Army Field Artillery/ Military Intelligence officer. He holds a bachelor’s degree in history from the University of Virginia and a master’s in strategic intelligence from the Defense Intelligence Agency’s Joint Military Intelligence College (now the National Intelligence University). He teaches Geographic Information Systems (GIS). His book, Steinstuecken: A Little Pocket of Freedom, the story of a West Berlin community surrounded by Communist territory during the Cold War, is now on sale.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments