By Major General Michael Reynolds

The political and military reasons for launching Operation Goodwood have been discussed in virtually every book written about the Normandy campaign.

In essence, by July 10, 1944, five weeks after D-day, the Allies were facing a crisis. The only large port in their hands, Cherbourg, was not yet operational, the Americans had failed to achieve their planned breakout, German occupation south of Caen was blocking the advance of the British and Canadians to the Falaise Plain, and insufficient ground had been captured in the Allied bridgehead for the forward airfields to be constructed.

Significantly, four German infantry divisions had reached Normandy in early July with the aim of releasing the panzer divisions for their classic counterattack role in operations against the Americans. British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, the overall Allied ground commander, was thus facing criticism from all quarters. If his declared strategy of breaking out from the west was to succeed, it was essential that he create a sufficient threat on the Caen flank to hold and attract the German armor, which might otherwise be used against the Americans.

Consequently, and having already failed to achieve a breakthrough to the west of Caen, Montgomery decided to launch a strong armored thrust on the east side from the Orne bridgehead. As he put it in a letter to Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke on July 14, “The Second [British] Army is now very strong … And can get no stronger … So I have decided that the time has come for a real ‘showdown’ on the eastern flank, and to loose [on 18th July] a corps of three armoured divisions into the open country about the Caen-Falaise road.”

This was to be followed by a breakout by the First U.S. Army around St. Lô (Operation Cobra) on the 20th. Both attacks were to be preceded by massive aerial bombardments.

In the case of the Second British Army sector, subsidiary attacks on the west side of Caen by the newly arrived XII Corps and the veteran XXX Corps were planned to last from the night of July 15 until the 17th. These attacks were designed to divert German attention and allow the British to gain what ground they could.

The Germans were certainly not distracted from the main threat; indeed, they predicted it precisely on July 16. An Ultra intercept revealed that the commander of Luftflotte (Air Fleet) 3, Field Marshal Hugo Sperrle, had signaled his units that a major British attack was “to take place south-eastwards from Caen about the night 17th-18th.” In the end, the diversionary attacks gained little ground and the cost was appalling: another 3,500 casualties.

The plan for Operation Goodwood was for three British armored divisions of General Richard O’Connor’s VIII Corps to carry out the main attack toward the enormously important and almost featureless Bourguébus Ridge to the southeast of Caen and the village of Vimont in the low, flat ground to its east. At the same time, Lt. Gen. Guy Simonds’s newly arrived Canadian II Corps, with its 2nd and 3rd Canadian Infantry Divisions and the 2nd Armoured Brigade, was to capture the southern part of Caen from Colombelles to Vaucelles, bridge the Orne, and be prepared to exploit south to a line from St. André-sur-Orne to Verrières, where it would hopefully link up with a British armored division. This part of the plan was code-named Atlantic; in addition, Lt. Gen. John Crocker’s I British Corps was to secure the left flank of the main assault by clearing the east side of the planned salient to a line from Emiéville through St. Pair to Troarn.

On July 15, Montgomery issued a personal memorandum to O’Connor in which he made clear his intentions for VIII Corps: “engage the German armour in battle and write it down to such an extent that it is of no further value to the Germans as a basis of the battle. To gain a good bridgehead over the Orne through Caen and thus improve our positions on the eastern flank. Generally to destroy German equipment and personnel, as a preliminary to a possible wide exploitation of success…. The three armoured divisions will be required to dominate the area Bourguébus-Vimont, and to fight and destroy the enemy.”

However, on July 17, just before the attack, Lt. Gen. Miles Dempsey, commander of the Second Army, restricted the VIII Corps objectives by specifying them as Vimont, Garcelles-Secqueville, St. Aignan de Crasmenil, Verrières, and Rocquancourt.

The German defenses facing Dempsey’s Second Army attack were considerable and, unknown to Allied intelligence, laid to a depth of some 12 kilometers. The two relevant corps of the German Panzer Group West in this sector were General Sepp Dietrich’s I SS Panzer Corps and General Hans von Obstfelder’s LXXXVI Corps. The latter, to the east of the Caen-Falaise road, had its 346th Infantry Division in position from the coast near Deauville to just north of Touffreville, and the remnants of the badly mauled 16th Luftwaffe Field Division from there to Colombelles.

The bulk of the 21st Panzer Division formed the third division in the LXXXVI Corps, and its 192nd Panzergrenadier Regiment with a Luftwaffe Panzerjäger battalion was positioned from Colombelles to the Orne bridge south of Caen.

Behind these screen forces was Kampfgruppe (KG) von Luck, named after the commander of the 125th Panzergrenadier Regiment of 21st Panzer Division, Major Hans von Luck. He had just been recommended for the Knight’s Cross and returned from three days’ leave in Paris on the morning of the attack. His KG consisted of his own 1st and 2nd Panzergrenadier Battalions and the 200th Sturmgeschütz Battalion. This latter unit was to play a critical part in the forthcoming battle. It had five batteries for a total of 30 self-propelled (SP) armored 75mm assault guns and 20 SP armored 105mm howitzers, all of which could be used in an antitank role.

These batteries were sited in or near the villages of Giberville, Démouville, Grentheville, Le Mesnil-Frémentel, and Le Poirier, all of which dominated the proposed British axis. On the eastern flank of the 21st Panzer Division, the 1st Panzer Battalion with 22 Mark IV tanks and the 503rd Heavy Panzer Battalion with 36 Tigers, including one company with Tiger IIs, were in position to support KG von Luck and to act as a divisional reserve. They were assembled under the cover of orchards, copses, and barns in the area from Sannerville to Emiéville. In addition, the 9th Werfer (rocket launcher) Brigade had been attached to LXXXVI Corps, and one of its battalions was sited near Grentheville, while a four-gun battery of a Luftwaffe 88mm flak battalion was near Cagny. It is noteworthy that there were no German antitank minefields, thus allowing freedom of movement for their armor.

Farther south, on the ridge behind Bourguébus, the Reconnaissance and Pioneer Battalions of the 21st Panzer Division were protecting the artillery of the three divisions of the LXXXVI Corps and, very significantly, an 88mm antitank battalion and two 88mm flak battalions with a total of 78 88mm guns were in the area of the Bois Secqueville. According to Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s records, there were 194 artillery pieces and 272 Werfers (1,826 barrels) in the sector. Unfortunately for the Allies, there were insufficient bombers available for these to be targeted during the morning of the 18th. Offers to attack them later were rejected by Dempsey, who believed that if he was to succeed at all his armor must by then have reached Bourguébus Ridge.

Dietrich’s I SS Panzer Corps was on the left of the Caen-Falaise road. The 272nd Infantry Division was in a forward position from the Orne bridge in Caen to near Eterville. The 25 Tigers of the Corps’ 101st SS Panzer Battalion (only 17 were operational on the day of the attack) were around Grainville-Langannerie, and SS Maj. Gen. Teddy Wisch’s 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte (LAH) was, unknown to British intelligence, in reserve in the area between Ifs and Cintheaux. However, its 2nd SS Panzer Battalion, 1st SS Stürmgeschutz (StuG) Battalion, 3rd SS Panzergrenadier Battalion in armored personnel carriers (SPWs), and 2nd SS (SP) Artillery Battalion were acting as a separate corps reserve on the west side of the Orne.

The other division of Dietrich’s I SS Panzer Corps, the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend (HJ), was still reorganizing and recovering after the recent heavy fighting. Its armored KG, under SS Lt. Col. Max Wünsche, had by July 17 moved to an area to the northwest of Lisieux. There it was joined by the newly activated 1st SS Panzerjäger Company HJ with its 10 new Jagdpanzer IVs. The rest of the 12th SS was some eight kilometers north of Falaise preparing to follow on. Suggestions that this move to the Lisieux area was part of a strategic plan by the German high command to meet any breakout to the east of Caen are incorrect. The 12th SS was directed there in response to Hitler’s fear of a second Allied landing between the Seine and Orne Rivers.

It has also been suggested that Rommel was personally responsible for the layout of the German defenses. This is not true, although his views would undoubtedly have been taken into account by the man who had the overall responsibility: the much respected and combat-experienced holder of the Knight’s Cross, General Heinrich Eberbach. He decided the basic structure of the Caen sector defenses, and the details were worked out by the two corps and six divisional commanders.

A strength report dated July 17 shows SS Lt. Col. Jochen Peiper’s 1st SS Panzer Regiment LAH with 59 Mk IVs and 46 Panthers combat ready, and Heinrich Heimann’s 1st SS Sturmgeschütz Battalion with 35 StuGs. The total number of operational armored vehicles available to the I SS Panzer and the LXXXVI Corps on the morning of July 18 was 219 tanks and 95 SP assault guns. However, 49 of these were with KG Wünsche, temporarily attached to another corps in the Lisieux area. In addition, there were eight Tigers, 30 Panthers, and 25 Mk IVs in short-term repair, giving a grand total of 377 German tanks, StuGs, and SP armored assault guns. This number was much greater than Allied intelligence estimated at the time.

There were a great many drawbacks to the Goodwood plan drawn up by Dempsey, approved by Montgomery, and due to be implemented by O’Connor with support from Simonds and Crocker. First, the bridgehead to the east of the Orne, from which the attack was to be launched, was far too small to accommodate three armored divisions—the Guards, 7th, and 11th. They would therefore have to follow one behind the other, not only across the three double bridges over the Orne and its canal between Ranville and the sea, but also through the protective British minefields that could not be gapped until the last moment as they were under German observation.

In fact, the Germans had a commanding view over the three double bridges and the whole Orne bridgehead from the Colombelles factories. After negotiating the minefields, the problems for the British were by no means over. The initial, very flat “corridor” along which the tanks were required to move was less than two kilometers wide for the first five kilometers, owing to the factory area of Caen on the west side and a forested ridge to the east. This meant that even after his armor emerged from the minefields, O’Connor would still be able to maneuver with only one of his three armored brigades.

Another significant problem was that after the first eight kilometers the leading tanks would be beyond the range of most of the artillery support, since the guns would be to the west of the Orne until all the tanks and infantry had cleared the bridges and assembly area. Only the few 25-pounder SP close support batteries moving with the forward tank battalions would be in range.

It is hard to imagine a worse or more complicated plan—three divisions with 877 tanks and over 8,000 vehicles being required to cross a canal and a river and then advance in column (six brigades one behind the other) through a minefield and along a narrow corridor to objectives 15 kilometers away.

To understand the Goodwood battle, it is important to begin by describing the ground over which it was fought. The main objective of the whole operation was the Bourguébus Ridge that overlooked the southern exits of Caen. The villages of Bras, Hubert-Folie, Bourguébus, and La Hogue at the northern and northeastern ends of this ridge dominated the whole very flat area to their north and east, an area that had little or no cover for attacking troops. They, like most Norman villages, have houses built of brick and stone and strong walls surrounding gardens, farmyards, and orchards, making them ideal for defense.

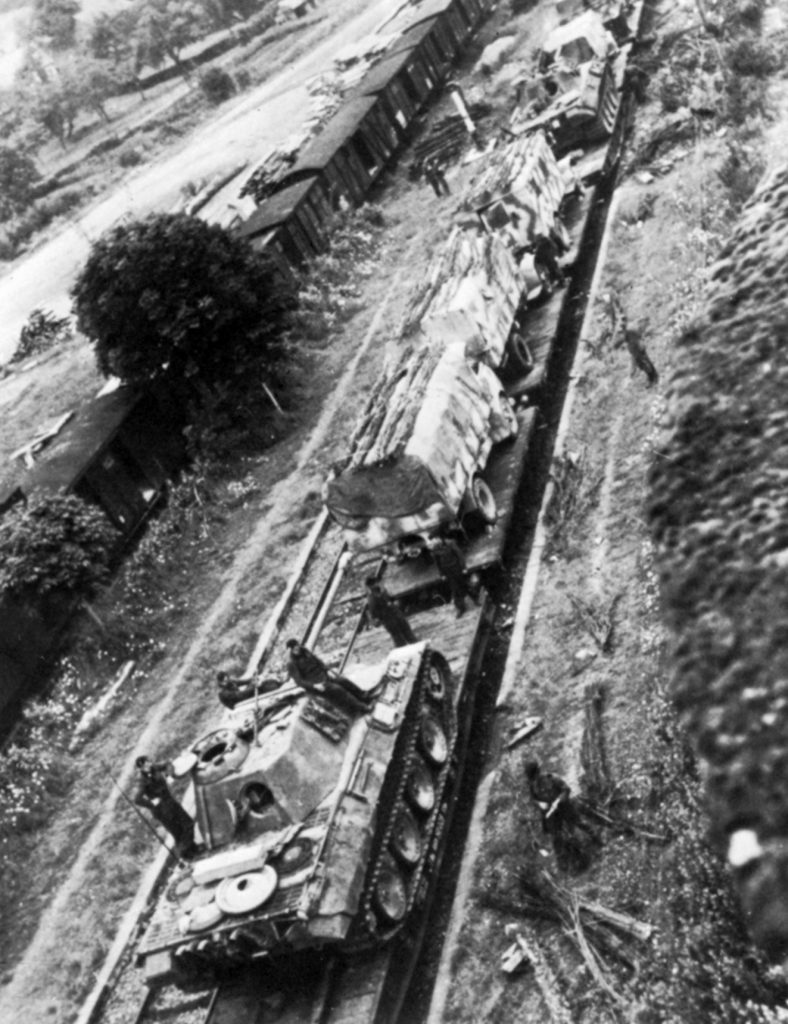

The railway lines from Caen to Troarn and Caen to Vimont were not obstacles, though they inevitably took a little time to cross. Much more significant, and usually not even shown on maps in most books, was the railway line coming out of the northeast part of Caen and then running south past the west side of Giberville and Grentheville between Hubert-Folie and Bourguébus and then past the west side of Tilly to the quarries and mines south of Grainville. It was significant because it ran along a high embankment from south of Giberville until it reached Bourguébus; it was a serious obstacle requiring even tanks to use its underpasses. It was also important because it was, and still is, impossible to see to the west of it from the villages of Le Mesnil-Frémentel and Grentheville. In effect, it divided the battlefield into two quite separate parts, the eastern part dominated by Bourguébus and La Hogue and the western by Hubert-Folie and Bras.

Despite stating that his men were “raring to go,” the commander of the leading 11th Armored Division, Maj. Gen. “Pip” Roberts, had severe misgivings about the plan, and he remonstrated about it with O’Connor, both verbally and on paper. He was concerned that, although his mission was to reach the high ground at Verrières and Rocquancourt on the western flank, he was first required to capture the villages of Cuverville, Démouville, and Cagny. This would necessitate the use of his 159th Infantry Brigade, an armored battalion, and an artillery battalion (half his division) and, as he put it, “make me fight with one arm tied behind my back.” O’Connor agreed that he need only “mask” Cagny until the following Guards Division cleared the village, but said the rest of the plan must stand. If Roberts did not like it, he would find another division to lead the attack. Roberts gave in.

The final plan was for the 11th Armored Division to take the high ground to the west, then for the Guards Armoured Division to follow and, after Cagny, swing to the east and reach Vimont. Maj. Gen. Bobby Erskine’s “Desert Rats” would then exploit south to Garcelles. A total of 200 guns were to provide a creeping barrage behind which the tanks would advance, and a further 350 guns, mainly mediums and heavies, were available to engage targets as required.

An air support signal unit was provided to enable each armored brigade and division to call in ground attack aircraft, and the leading brigade, the 29th, had with it a RAF liaison officer in a tank who could talk directly to the fighter bombers. Significantly, his tank was knocked out early in the battle. German tank and antitank gunners were trained to engage command and special tanks as a top priority.

Operation Goodwood began at 0525 hours on July 18, 1944, with an artillery barrage against known and suspected antiaircraft batteries. Ten minutes later, 1,100 British heavy bombers dropped a carpet of high explosive bombs on the eastern parts of Caen, the area from Touffreville to Emiéville, and in the vicinity of Cagny. They were followed at 0700 hours by 482 Allied, mainly American, medium bombers that used fragmentation bombs on the axes of the armored divisions, while 300 fighters and fighter bombers went for known strongpoints and gun positions.

Dust and smoke from the initial attacks made it difficult for aircraft in the later waves to find their targets, and many had to abort their missions. Then, for half an hour starting at 0800 hours, 495 American heavy bombers dropped further fragmentation bombs designed to do maximum damage to the defenders but not to impede the advance of the British tanks. Some of these planes also had trouble with smoke and dust, as did fighter bombers later in the day. They had great difficulty finding targets on what became a very confused battlefield. A total of 7,700 tons of bombs were dropped. Major Bill Close, a leading tank company commander later recalled, “It really did seem that nothing could live under the bombardment, but how wrong we were!”

Most of the forward German positions were destroyed, and the panzer reserves in the Sannerville-Emiéville area were badly hit, but amazingly, all the armored assault gun batteries except the one in Démouville survived, as did most of the rest of KG von Luck. Even the panzergrenadier battalion in Colombelles was able to withdraw later under the cover of darkness with remarkably few casualties.

It is also worth mentioning that the commander of the 3rd Company of the 503rd Tiger Battalion, Lieutenant (later Bundeswehr Major General) Freiherr von Rosen, personally described to this author in 1981 how one of his 57-ton tanks was literally turned upside down by the force of the explosions. One of his men was driven insane, and two more committed suicide during the attack. Four of his Tigers were destroyed, and the rest had to be dug out of the earth and debris that covered them. That his company recovered to fight at all on that first morning is an indication of its high morale and professionalism.

The I SS Leibstandarte and 12th Hitlerjugend Panzer Divisions were virtually unaffected by the bombing, as was the Corps’ 101st SS Heavy Panzer Battalion.

In order not to arouse German suspicions, when in fact they were fully aware that a major attack was coming that morning due to the noise made by so many tanks, only the 29th Armored Brigade crossed into the bridgehead east of the Orne before H-hour. When the artillery barrage opened up at 0745 hours, some of the shells fell short, killing and injuring a number of the forward tank crews who were out of their vehicles awaiting the order to advance.

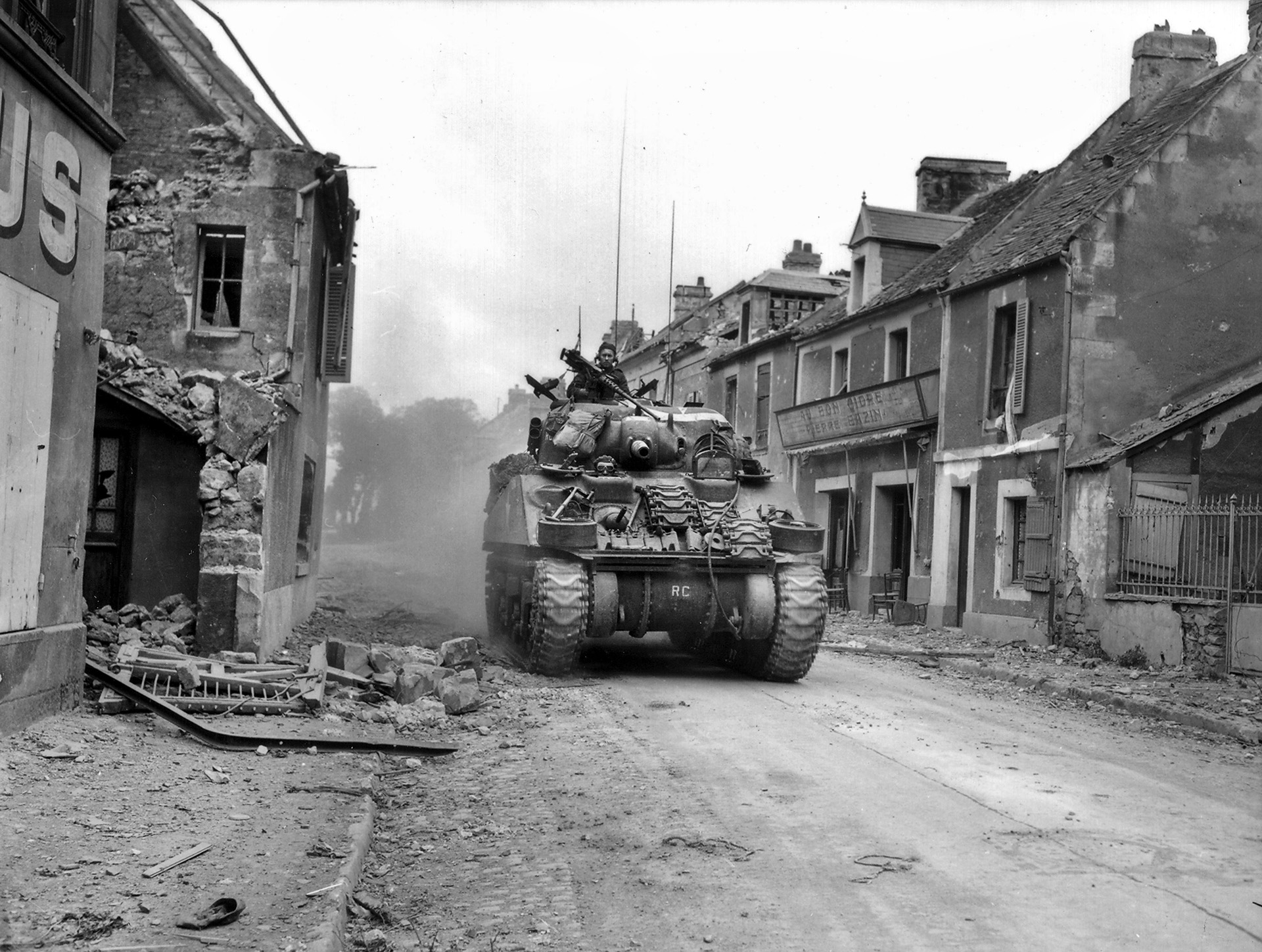

According to Major Close, “This happening a few seconds before we were to start added considerably to the confusion, and we set off after the barrage in some disorder.” Dust, smoke, and cratering in the path of the two leading tank companies, trying to advance with 32 Shermans in line abreast, soon added to the chaos. Fortunately for them, they met no opposition before the Caen-Troarn railway line, which they reached at 0830 hours. Even though the artillery barrage was advancing at a rate of only eight kilometers per hour, the leading tanks were soon left behind.

At the railway, there was a planned 15-minute pause to allow the tanks to cross and sort themselves out, but even then not all could catch up. In fact, they averaged only a walking pace in the first hour and a half. Not surprisingly, the second tank battalion, which was meant to come into line after emerging from the minefield, soon caught up with the rear tanks of the leading unit and added to the confusion. The brigade’s third tank battalion dropped back due to the traffic congestion and poor visibility.

Shortly after 0900, the main artillery barrage ended and the tanks were on their own except for their own close-support SP batteries.

The two leading tank battalions pushed on toward the Caen-Vimont railway line and at last, between the Troarn and Vimont roads, they managed to change from column to line, with one passing to the west of Le Mesnil-Frémentel and the other to the east. As the latter crossed the Caen-Vimont road at about 0930, the rear company, together with a supporting motorized infantry company and SP artillery battery, was suddenly engaged by assault guns from positions in Le Mesnil-Frémentel and Le Poirier. Twelve Shermans went up in flames.

The German gunners had deliberately let the two leading companies pass unhindered, for they were to be dealt with by other assault guns in Grentheville. The commander was skillfully withdrawing his batteries in accordance with the British advance, and three of them would shortly take up new positions to the southeast of Four and in Soliers and Hubert-Folie. The 159th Infantry Brigade, which would have been invaluable in dealing with these assault guns, was fully engaged clearing the villages of Cuverville and Démouville to the north.

The leading tank company on the right flank also lost six of its Shermans to fire from Le Mesnil-Frémentel and was now faced with the problem of the north-south railway line running along the steep embankment. Its commander, Major Close, led the rest of his tanks under an embankment bridge at about 1000 hours and deployed without further loss one kilometer short of the Cormelles factory area. The remainder of the battalion and accompanying infantry company soon followed, but at noon ran into effective antitank fire from Bras and Hubert-Folie and even some 88mm fire from Bourguébus. This could have come from Tigers of SS Captain Michael Wittmann’s 101st SS Heavy Panzer Battalion. Sherman after Sherman went up in flames.

During the morning, General Eberbach had become aware of the size of the Allied attack and particularly of the threat along the line of the Caen-Vimont railway. He therefore ordered Dietrich—who was focusing on the Canadian attack out of the center of Caen but was also aware of the threat to the right flank of his corps—to move the Leibstandarte to the area of the Bourguébus ridge and launch a counterattack as soon as possible.

Dietrich agreed to release back to the Leibstandarte that large part of the division that was still west of the Orne. The 1st SS Panzer Battalion (46 Panthers) was to advance from the area east of Rocquancourt, through Cagny, and push the enemy back across the Caen-Troarn railway line. It was to be assisted by the 2nd SS Panzer Battalion and the 1st SS StuG Battalion as soon as they arrived from west of the Orne. Panzergrenadiers from both the Leibstandarte’s regiments were to advance to and hold the Four-Soliers area and secure Bras. With admirable speed, the first reconnaissance elements of the Leibstandarte arrived in the Bourguébus area around 1200 hours.

The movement of the 1st SS Panzer Regiment to the battle area went undetected by Allied aircraft. Its arrival on the Bourguébus ridge at about 1245 hours coincided with that of the two remaining British tank companies of the left-flank battalion, which were advancing past Four toward Soliers and the ridge running from Bourguébus to La Hogue. Within minutes, the regiment lost 29 tanks, including its commanding officer’s. The situation was so bad that at 1258 hours the reserve tank battalion of the brigade in the Grentheville area was ordered not to advance south of Soliers.

Allied fighter bombers were very active during the day, but seem to have had difficulty finding and effectively engaging the German armor in the dust, smoke, and general confusion of the battlefield. The main problem was that after the tank with the RAF liaison officer was hit during the morning, no one on the ground was really capable of talking directly to the pilots and giving the required targets.

Behind the 29th Armored Brigade there had been increasing chaos as units became delayed and mixed up. Worse still, as the leading tanks of the 5th Guards Armored Brigade approached Cagny at 1015 hours, they were engaged by the four Luftwaffe 88s von Luck had ordered, at pistol point, to take up antitank positions in the northwest part of the village. These guns had to be dealt with before any further advance could be made, and while one tank battalion tried to do this, the other two bypassed Cagny at about 1230 hours. They took a detour through Le Mesnil-Frémentel to advance along the line of the railway to Vimont. Unfortunately, this put them right across the path of the 7th Armored Division and only added to the confusion.

The 7th Armored Division had asked the VIII Corps headquarters for assistance at 1145 hours but, as the 7th Divisional War Diary put it, “[7th Armoured was] badly congested by the Guards Armoured Division who came too far west and blocked our exit against the 11th Armoured Division.”

In the meantime, one of the tank battalions advancing on Cagny was hit by a counterattack from the remains of the 21st Panzer’s armored reserve consisting of up to 10 Tigers and nine Mk IVs. This failed when two of the Tigers were mistakenly engaged and knocked out by the Luftwaffe 88s in Cagny. The remaining tanks withdrew and were then ordered to Frénouville, where von Luck’s headquarters was located, and the Le Poirier area, with a view to blocking the open German flank to the southeast of Caen.

At 1430 hours, the reserve tank battalion of the 29th Armored Brigade was ordered to advance past the sad remains of the left flank unit toward Soliers and Four. It was soon halted by assault guns in Soliers, the tanks of the Leibstandarte on the ridge, and the German armor in the area of Le Poirier and Frénouville. As they tried to withdraw, just before 1500 hours, every tank in the leading company was destroyed.

The unit history relates, “With no time for retaliation, no time to do anything but take one quick glance at the situation, almost in one minute, all its tanks were hit, blazing and exploding. Everywhere wounded or burning figures ran or struggled painfully for cover, while a remorseless rain of armour-piercing shot riddled the already helpless Shermans.”

By 1506 hours, the remnants of the left-flank battalion had withdrawn to the north of the Caen-Vimont railway line. Twenty-two minutes later the unit on the west flank, which had already pulled back to the north-south railway line at 1400 hours, reported the ground to its front “covered by tanks and anti-tank guns.”

At 1600 hours, when “Pip” Roberts met his corps commander and the commander of the 7th Armored Division just behind Le Mesnil-Frémentel, his armored brigade was in complete disarray and his infantry brigade was still tied up at the north end of the corridor. Grentheville had been cleared, but Frénouville, Four, Soliers, Le Poirier, La Hogue, Bourguébus, Hubert-Folie, and Bras were all in German hands.

Roberts had already called forward his only armored reserve, the Divisional Armored Reconnaissance Battalion, and he demanded, not unreasonably, that the 7th Armored Division move forward to fill the gap between himself and the Guards. However, the 7th Armored had been seriously delayed getting through the minefields and, as previously stated, further disrupted in its advance in the narrow corridor north of Le Mesnil-Frémentel. It has been suggested that its commander, who certainly thought the whole operation was a waste of armor, displayed undue caution on this day and perhaps deliberately delayed his leading armored battalion, saying there was no way between the 11th Armoured Division and the Guards.

This is difficult to believe because it would have required the collusion of both the brigade commander and the unit commander, not to mention the various staffs. Whatever the truth, the leading battalion did not arrive at the Caen-Vimont railway line until 1800 hours, and by then it was too late to help. It had taken two hours to move the three kilometers from the Caen-Troarn road to Grentheville!

In the meantime, the 32nd Guards Brigade had reached Cagny at 1600 hours. The 88mm gun crews blew up their guns before withdrawing, but it took until 2000 hours before the village was finally cleared. Le Poirier fell at 1630 hours. Attempts to advance on Vimont at 1900 hours again failed in the face of German tanks and assault guns around Frénouville. The War Diary of the Guards Armored Division says 60 Shermans were damaged during the day, of which 15 were knocked out.

At 2000 hours, the 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Battalion of the 1st Regiment arrived to join the Leibstandarte’s StuGs in Bras. The latter claimed to have surprised some 15 to 20 tanks on the northern edge of the village earlier in the evening. These were the Cromwells of the 11th Armored Division’s Armored Reconnaissance Battalion, which Roberts had committed in a final attempt to achieve his mission. Sixteen of them were lost in this forlorn attempt to take the ridge from the north.

By the time darkness fell, the remnants of 11th Armored’s four tank battalions had withdrawn to the north of Soliers and the Caen-Vimont railway line. The 29th Armoured Brigade had lost at least 125 Shermans during the day’s fighting. The 159th Infantry Brigade had finally caught up and was dug in around Le Mesnil-Frémentel. With the 32nd Guards Brigade in defense around Cagny and the 5th Guards Armored Brigade to the west of a line from Emiéville to Frénouville, the situation at the southern end of the “armored corridor” was both crowded and confused.

One of the excuses given for the VIII Corps debacle on July 18 was a lack of infantry. Hans von Luck, in his book Panzer Commander, certainly criticized British tactics. He pointed out that the tank attacks were almost always carried out without infantry support and there was therefore no one immediately available to eliminate troublesome antitank nests. This is an overstatement in that a motorized infantry battalion was an integral part of each of the two armored brigades involved, but it is certainly true that the potential of the three infantry brigades in VIII Corps was largely wasted.

A plan that deprived the leading armored division of its infantry brigade, a lack of armored personnel carriers, and poor cooperation between infantry and armor ensured that the British tanks in Goodwood operated virtually unsupported. There were 12 infantry battalions available in VIII Corps, three of them mechanized, to support nine tank and three armored reconnaissance battalions, and yet five of them saw no action at all on July 18.

Despite the terrible tank casualties in O’Connor’s VIII Corps, the cost in human terms was surprisingly light—521 in all, and only 81 killed in the four tank battalions of the 11th Armored Division. Even more surprising, the four infantry battalions of the same division suffered a total of only 20 casualties.

In the meantime, the Canadians had cleared the Colombelles factory area, penetrated into Vaucelles and, early on the 19th, bridged the Orne—all at a cost of less than 200 men. The Germans withdrew from the Caen suburbs during the night and took up new positions on the western end of the Bourguébus ridge where the bulk of the Leibstandarte was now located.

On the eastern flank, the 3rd British Infantry Division and other troops of I British Corps cleared Touffreville and Sannerville during the day and reached the outskirts of Troarn, but attempts to advance farther south were firmly blocked by the German defenders in the Emiéville and St. Pair sector. The cost had been relatively heavy, 651 men and 18 tanks, but this time the bombing had undoubtedly helped the attackers.

In summary, at midnight on the 18th the Germans had lost Caen, but were still holding all the villages to the south of the Caen-Vimont railway except Grentheville, and were defending a firm line running north from Frénouville through Emiéville to Troarn.

During the night, the Leibstandarte reorganized slightly, giving the 1st SS Panzergrenadier Regiment responsibility for the Bras, Hubert-Folie, and Bourguébus sector and the 2nd Regiment the area of Le Poirier, Four, Soliers, and La Hogue.

But what had happened to the 12th SS Panzer Division? There is a general belief that two strong Hitlerjugend KGs with tanks were sitting in reserve north of Falaise on July 17, and that on the 18th they were used to thicken the German defenses to the southeast of Caen and repel the British Guards and 11th Armored Divisions. Not so. The part of 12th SS in the Falaise area, in terms of combat-ready troops, consisted of little more than one KG under the command of SS Major Hans Waldmüller.

On July 17, General Eberbach, suspecting that the British were about to attack, cancelled the plan for this group to join KG Wünsche northwest of Lisieux, and at about midday on the 18th, worried by the strength of the VIII Corps attack, asked the high command if he could use the Hitlerjugend Division. However, permission could not be given without consent from Berlin since, on July 16, Hitler had expressed his intent to preserve the division.

The 12th SS Panzer Division was released to I SS Panzer Corps at 1500 hours on the 18th and ordered to take over the sector from Emiéville church to Frénouville from 21st Panzer as soon as possible.

Interestingly, the Germans had appreciated that the ground due east of Vimont, along the Route Nationale 13, was quite unsuitable for armored forces, being only just above the water table. KG Wünsche was therefore wasted near Lisieux. The more likely British axis was through Airan and then on to cross the Dives River near St. Pierre-sur-Dives, so it was decided to concentrate the 12th with its center in the Vimont area. While it would not be too difficult to move KG Waldmüller forward during the night, the destroyed bridges over the Dives would present serious problems for Wünsche. All concerned knew that the Hitlerjugend Division could not be fully in position before midday on July 19. Fortunately for the Germans, the British were to allow the necessary time.

During the night of July 18-19, the Luftwaffe made one of its few effective raids against the British bridgehead east of the Orne. It caused heavy casualties among some of the administrative echelons and replacement tank crews for the Guards and 11th Armored Divisions. The vital bridges were not hit.

Although both the forward British armored divisions had full-strength infantry brigades available and in the right place, neither attempted the one operation the Germans were dreading: a night attack by infantry. Instead, they “consolidated their gains.” Moreover, VIII Corps took no offensive action during the morning of July 19 either. It was “reorganising for further action.” The Germans, on the other hand, were active. At 0700 hours a counterattack from Four by a company of the 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Regiment recaptured Le Poirier.

O’Connor met his three divisional commanders at midday and told them to resume their attacks. The 11th Armored Division was to capture Bras and Hubert-Folie beginning at 1600 hours, and then at 1700 hours the 7th Armored was to capture Bourguébus, now known to the soldiers as “Buggersbus.” Then it was to advance to Tilly-la-Campagne and Verrières, while the Guards were directed to retake Le Poirier and then advance to Vimont.

Besides carrying out the counterattack against Le Poirier, the men of the Leibstandarte spent the morning improving their defenses and preparing further ones in depth. Lieutenant Werner Wolff’s 7th SS Panzer Company joined the 3rd SS Panzer Company in the Tilly area, and the rest of the 1st SS Panzer Battalion moved up behind the ridge to the east of Bourguébus.

As a result of observed British movements, only two StuGs were left in Bras. The 3rd SS Panzergrenadiers and the remainder of the Stürmgeschutz Battalion were moved to better positions between the village and Hubert-Folie which, along with Soliers, was held by the 1st Battalion of the 1st SS Panzergrenadier Regiment. The 2nd SS Battalion was defending the ridge from Bourguébus to Tilly, and SS Lt. Col. Rudolf Sandig’s 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Regiment continued to defend the right flank of the Leibstandarte sector in Le Poirier, Four, and La Hogue.

The leading elements of Kurt Meyer’s 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend arrived in the forward area at 0530 hours on the 19th, and by midday a KG had taken over for the 21st Panzer Division on both sides of the Cagny-Vimont road at Frénouville. The Divisional Escort Company was behind it at Bellengreville.

Another KG also arrived on the high ridge running north-south in the Argences-Moult-Airan area around noon. It was an ideal location for the divisional reserve. During the afternoon, SS Panzergrenadiers moved in on the right flank and occupied Emiéville. The 8th SS Panzer Company took up ambush positions astride the Vimont road between two panzergrenadier battalions and, while the 12th SS Pioneer Battalion lay mines and constructed obstacles throughout the sector, the 1st SS Panzerjäger Company provided depth behind Frénouville.

Thirty-six replacement Mk IVs destined for the 2nd SS Panzer Battalion were still in transit and did not arrive in time for the fighting on the 19th. Nevertheless, for the first time since its official formation in 1943, the two designated divisions of Hitler’s I SS Panzer Corps Leibstandarte were to fight side by side.

On the afternoon of July 19, elements of the 32nd Guards Infantry Brigade attacked Emiéville, but were beaten off by SS panzergrenadiers who suffered a loss of only two killed and six wounded. A larger attack at 1900 hours by the same brigade easily retook Le Poirier. The company of the Leibstandarte’s 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Battalion that had been defending it had by then withdrawn, under orders, to Four. However, further attempts by the Guards to advance on Frénouville failed. The 5th Guards Armored Brigade inexplicably remained idle. Its War Diary records, “It was reported that a screen of 88s barred any further progress in the direction of Vimont and it became more important that we should hold Cagny so that the 7th and 11th Armoured Divisions on our right flank should be able to advance.”

The attack by the 11th Armored Division began at 1600 hours with the Divisional Armored Reconnaissance Battalion advancing on Bras from the northwest. It was followed by a tank battalion, which, once Bras was secured, had the task of capturing Hubert-Folie. However, by 1620 hours it was clear that the attack on Bras had failed, and it was decided to mount a second attack from the northeast. One of the two StuGs that had been left in Bras withdrew after the other was lost, leaving the panzergrenadiers without close armored support. A member of the 9th Company remembered later, “The tanks rolled up. Two, five, eight, ten, we stopped counting. They approached our foxholes carefully. Dread and fear paralyzed us. We knew they would pulverize us. Those of us who survived were taken prisoner.”

At 1710 hours, the British tanks emerged on the southwest side of the village, and by 1730 the supporting infantry was mopping up.

Following the fall of Bras, the Armored Reconnaissance Battalion was ordered to advance on Hubert-Folie at 1810 hours, but the village was defended by parts of the 1st SS Grenadiers and the 2nd SS StuG Company, and after 20 minutes the advance broke down in confusion. Even so, when the remaining 25 or so British tanks advanced again on Hubert-Folie at 2000 hours they found no enemy. The Leibstandarte defenders had withdrawn to the dominating ridge two kilometers to the south, near Verrières, where Peiper’s tanks were already in position.

The concurrent attack by the 7th Armored Division’s 22nd Armored Brigade against the Leibstandarte forward defenses in Four and Soliers was initially delayed by SS panzergrenadiers, but after a short time they fell back, again under orders, to the Bourguébus-La Hogue ridge. Then, as the British tanks surged forward just before 1900 hours on either side of Bourguébus, they ran headlong into Peiper’s 1st SS Panzer Regiment and lost eight Shermans. There was little option but to pull back into Four and Soliers.

Hitler’s Leibstandarte Corps had, for all intents and purposes, held firm. The Hitlerjugend had given no ground and, as darkness fell, the Leibstandarte was still holding the vital ground from La Hogue through Bourguébus to Beauvoir.

Meanwhile, on the 19th, the Canadian 2nd Infantry Division had cleared Cormelles, Fleury-sur-Orne, Hill 67 just to the north of St. André, and Ifs. This placed the Canadians in a good position to take over Bras and Hubert-Folie on the following day and relieve the badly mauled British 11th Armored Division.

At 1000 hours on July 20, Dempsey ordered the 7th Armored Division to complete the capture of Bourguébus. At the same time, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division was to advance and establish itself on the Verrières feature astride the Caen-Falaise road.

When the 7th Armored Division began its advance it found Bourguébus abandoned by the Leibstandarte’s 1st SS Panzergrenadiers, but when its tanks tried to continue across the gently rising ground toward Verrières they came under heavy fire and were stopped in their tracks. The Leibstandarte, supported by tanks of Wittmann’s 3rd Tiger Company, was as usual on the vital ground. But the British 22nd Armored Brigade was not the only formation attacking Verrières on the morning of the 20th.

The Canadians had also been ordered to take the ridge, and their 6th Infantry Brigade had crossed the Orne that morning. After hurried consultations between the II Canadian and the VIII British Corps, it was agreed at midday that the British would withdraw to the east of the Caen-Falaise road and provide fire support for the Canadian attack. The British got the best deal.

Meanwhile, the Guards Armored Division had occupied Frénouville and Emiéville after SS panzergrenadiers had abandoned both. These withdrawals were carried out to shorten the Hitlerjugend’s line, but further attempts by the Guards to advance toward Vimont were strongly resisted and failed. Low, threatening clouds precluded any Allied air support. The new 12th SS line ran from just east of Emiéville to a point halfway between Frénouville and Bellengreville.

The Canadian attack against Verrières began at 1500 hours. It was supported by both Canadian and British artillery and Typhoon ground attack aircraft. Despite the fact that this was a full-scale attack, the infantry advanced on its own, unaccompanied by tanks, which for some strange reason were held back in a counterattack role. A foothold was secured in the relatively unimportant village of St. André-sur-Orne, defended by the 272nd Infantry Division, and by 1730 hours the Canadians reported that they had companies in the Beauvoir and Torteval farms.

Despite a violent rainstorm that turned the ground into a sea of mud, the inevitable German counterattack hit the Canadians a short time later. It was mounted from the direction of Verrières by the 5th and 6th Companies of the 2nd SS Panzer Battalion supported by a StuG company and elements of the 1st SS Panzergrenadier Regiment. The Canadians were overrun and suffered 208 casualties, including the commanding officer and 65 men killed. The same German force then turned on the follow-up Canadian unit that had moved up to occupy the area between Beauvoir and St. André, causing it heavy casualties. By 2100 hours two of its companies had been broken.

Heavy fighting continued throughout the night of July 20-21, as did the torrential rain, terminating any hopes Montgomery, Dempsey, O’Connor, or anyone else might have had of continuing Goodwood.

On the morning of the 21st, the Leibstandarte launched another heavy counterattack against the Canadian center, causing more casualties and recapturing the vital Torteval and Beauvoir farms. The strategic Verrières ridge was back in the hands of the Leibstandarte, and the largest armored battle ever seen in the history of Western Europe—over 1,200 tanks and armored assault guns involved—was over.

The strategic results, failures, successes, and implications of Operation Goodwood have been discussed many times. This author will confine himself to four basic statements. First, of the four objectives specified by Dempsey—Vimont, Garcelles, Hubert-Folie, and Verrières—only Hubert-Folie had been captured, and one assigned by Montgomery, Bretteville-sur-Laize, was still over eight kilometers away.

Second, Montgomery’s aim of “writing down” the German armor had not been achieved.

Third, the cost for what was achieved was enormous. British losses in the VIII and I Corps only were 3,474, and Canadian casualties amounted to 1,965, including 441 dead. Reports that the British lost over 400 tanks are much exaggerated. A careful study of the relevant documents indicates a maximum of 253 for the period of Goodwood, and many of these were repairable.

Fourth, Montgomery’s vital aim of holding the bulk of the German armor on the eastern flank, to prevent it from being used against the intended American breakout in the west, was achieved.

With regard to “writing down” the German armor, the claim in the British official history that the Leibstandarte and 21st Panzer Divisions lost 109 tanks on July 18 is certainly another exaggeration. One can, however, account for 41 tanks and six assault guns knocked out in the initial bombing, and the commander of the Leibstandarte mentions a figure of 12 Panthers and one Mk IV lost on the same day. It is also known that the Leibstandarte Sturmgeschütz Battalion had 17 StuGs knocked out or badly damaged on the 18th and 19th, although only two of these were total write-offs.

It is confirmed that the 12th SS suffered no tank casualties during the fighting and that on July 20 the Leibstandarte still had 17 Panthers and 46 Mk IVs operational. Therefore, the figure given by Maj. Gen. Roberts, commander of the 11th Armored Division, in an interview at the British Staff College in 1979 that was used in the British Army training film on Goodwood, of 75 German tanks and assault guns destroyed can be accepted as accurate. This is only 20 percent of the total German armored strength in the I SS Panzer Corps sector and cannot possibly be described as the “writing down” of armor as required by Montgomery.

German casualties were relatively light. The Leibstandarte lost 1,092 men, including 243 killed, from July 16 to August 1. In the case of the Hitlerjugend, most casualties were caused after Goodwood by Allied artillery fire. The total loss from July 19 to August 4 was 134, including 18 killed.

The failure of Goodwood to achieve a breakthrough caused a major row in the highest echelons of the Allied command. Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower was furious and made his famous remark that the Allies could hardly expect to advance through France at a rate of a thousand tons of bombs per mile. Marshals Arthur Tedder and Trafford Leigh-Mallory and all the senior air commanders were equally angry. Many officers at SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) wanted Montgomery sacked and Eisenhower himself to take command of all land forces.

Even Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who was never particularly fond of Monty, began to have doubts about his ability. There is little doubt that while Montgomery would remain a hero to most of the British fighting soldiers who served under him, his reputation with many senior officers and military historians would be forever tarnished. Sadly for him, his chance of remaining overall Allied land force commander ended with Goodwood.