As terrible as the fighting at Okinawa had been, and as costly as the struggle had proven to be in terms of lives and equipment, there is no doubt that the nearly two-month struggle for control of the island would have been dwarfed by what might have come next.

By early 1943, it had become apparent to American military planners that the initiative in the Pacific War was being wrested from the Japanese. Important victories at Midway and Guadalcanal had marked the limit of Japanese expansion, and the long, hard road to Tokyo stretched ahead. Given the ferocity of the resistance already encountered, it also appeared that nothing short of the conquest of Japan itself could end the war on satisfactory terms. During the campaigns to come, fighting on islands such as New Guinea, Tarawa, Peleliu, Saipan, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa seemed to confirm the grim necessity of an invasion of Japan.

Planning for such an operation began in earnest early in 1945. Code-named Operation Downfall, the invasion was envisioned with two components, Olympic and Coronet, which were scheduled for November 1, 1945, and March 1, 1946, respectively.

Downfall would eventually involve 4.5 million fighting men, every vessel in the U.S. Pacific Fleet, and thousands of landing craft, support ships, vehicles, and planes. It was significantly larger than the D-day invasion of France’s Normandy coast on June 6, 1944. Okinawa would serve as a giant staging area, teeming with the materiel of war.

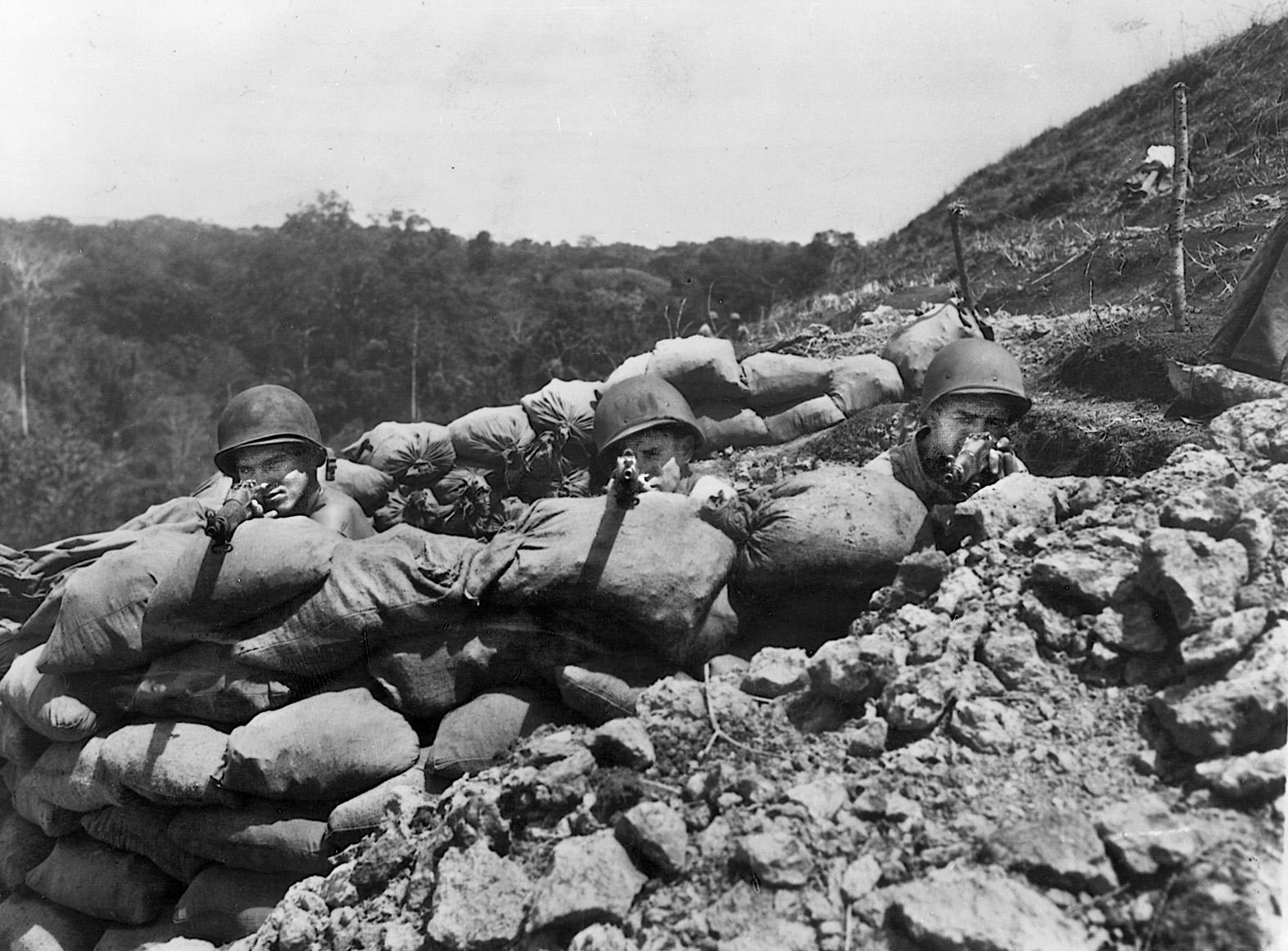

Operation Olympic was to hurl 11 Army and three Marine Corps divisions ashore on Kyushu, the southernmost of the Japanese islands. This 650,000-man assault force was expected to land on a 250-mile front along the coast. It was also certain to encounter fanatical resistance similar to that of the defenders of Okinawa. The terrain was rugged, with steep cliffs and caves that the Japanese had honeycombed with tunnels, pillboxes, machine-gun nests, and artillery positions.

Scheduled four months later and twice the size of Olympic, Operation Coronet was to include as many as one million Allied troops in up to 28 divisions. These forces were to land on the main and largest island, Honshu, advance steadily inland, and occupy Tokyo.

Some planners believed that if all went according to the book, World War II would be over by December 1946. However, as was evidenced by the Normandy landings and previous amphibious assaults in the Pacific, the plans might well go awry as soon as the first troops hit the beaches.

The Japanese had undoubtedly done some planning of their own with the intent of driving the invaders back into the sea. In addition to strongly prepared defensive positions and difficult terrain, the Allies could anticipate encountering a defensive force of approximately two million troops. These were backed by a civilian population of roughly 10 million, some of whom had been trained, albeit crudely. Thousands of kamikaze aircraft had been secreted away for use in repelling an invasion.

While the enemy could be expected to fight to the death, Allied casualties were estimated to run as high as one million.

When Okinawa fell in June 1945, very few people knew that an alternative to the invasion existed. President Harry Truman himself had not known until he had assumed the role of chief executive following the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that April. Working within the framework of the Manhattan Project, scientists had developed a method of sustaining a nuclear chain reaction and produced the world’s first weapon of mass destruction.

Knowing that testing had been successful in July, Truman made the fateful decision to use the bomb the following month. When Hiroshima and Nagasaki were destroyed, Japan was forced to the peace table.

The president’s decision has been and will continue to be hotly debated, but the voice of one group is clear. It is the voice of a generation who would never have been born if their fathers had died on battlefields in Japan, the children of Operation Downfall. n

Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments