By Arnold Blumberg

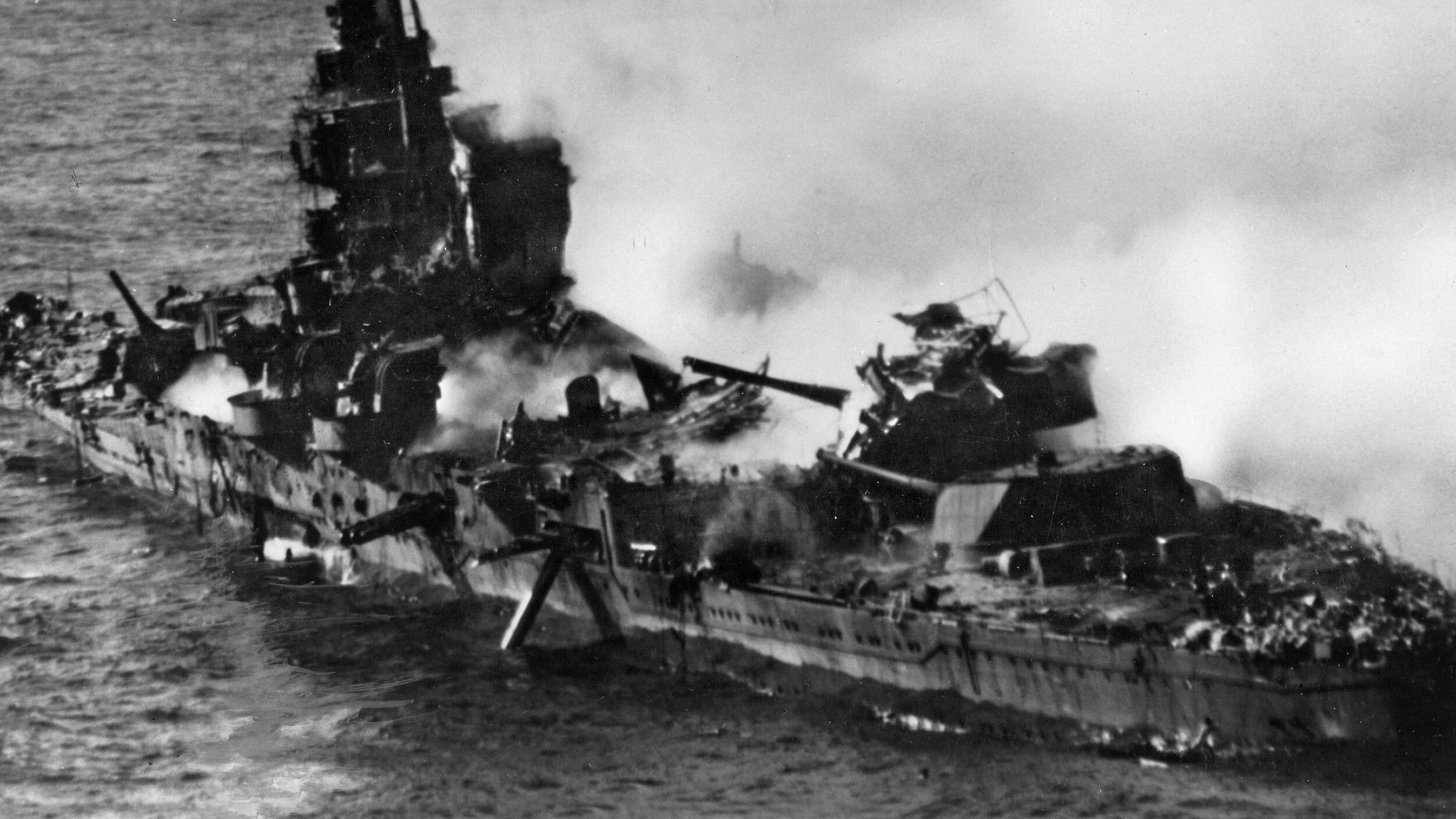

By June 1942, the military might of Imperial Japan threatened Australia. The string of spectacular Japanese conquests in the South Pacific menaced lines of supply and communication between the United States and its allies and bases in the region.

The initial threat would come from airfields established on the islands of Guadalcanal, Tulagi, Florida, and Savo, all in the Solomons archipelago. Allied bases in the New Hebrides, Fiji, and New Caledonia could be interdicted by Japanese airpower, seriously hindering, if not forestalling, any Pacific counteroffensive against Japan.

Eager to take the fight to the Japanese, Allied planners searched for an opportunity to hit back. Situated closest to concentrations of Allied forces in the Pacific, Guadalcanal became a likely target, and a plan for an amphibious assault to capture the enemy airfield being constructed there was devised by the U.S. military. The island was located halfway between Allied bases in the New Hebrides and the major Japanese naval base at Rabaul on the island of New Britain. The capture of Guadalcanal would allow the Americans to base airpower on the island. This, in turn, would not only make for an easier defense of the lines of communication with Australia, but also provide a jumping off point for offensive action against enemy positions in the Bismarck Sea and on New Guinea.

A Dress Rehearsal with Few Records

Although at the time a rehearsal was considered vital before the U.S. Navy launched its initial seaborne attack of World War II, information about the four-day operation off the coast of Koro in the Fijis at the end of July 1942, just 10 days before the actual invasion of Guadalcanal, is strangely absent from the literature of the Pacific War. Neither the official Navy and Marine Corps histories nor other authoritative accounts more than briefly acknowledge its existence. Even high-profile participants in the Guadalcanal operation barely mention it in their postwar accounts.

Marine Corps Maj. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift, who led the 1st Marine Division in the landing on Guadalcanal, simply gave a brief assessment in his autobiography, while his assistant operations officer, Merrill Twining, in his published memoir, mentions the planning of the exercise and the problem of naval gunfire support, but no information about the rehearsal itself other than the coral conditions found around the island.

The dearth of official and other accounts of what occurred during the execution of the practice would indicate that it was of only marginal significance to the operation at Guadalcanal. But the facts show otherwise. More likely, scant mention of the rehearsal was due to the glaring lack of preparedness in amphibious warfare on the part of the commanders and the troops who took part, as well as serious weaknesses in the ability of the Navy to support such a mission. As a result, it is not surprising that neither the Navy nor the Marine Corps at the time, or after the war, wanted to cast light upon an operation that was so flawed.

The Plan on Paper vs the Plan in Practice

To implement its new offensive strategy in the Pacific, the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff issued in early July 1942 its “Joint Directive for Offensive Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area Agreed by the United States Chiefs of Staff.” This blueprint provided for the seizure of the islands of New Britain, New Ireland and New Guinea to be carried out in stages. The conquest of Guadalcanal in the lower Solomons would be set in motion first, followed by the taking of portions of the upper Solomons and parts of New Guinea, and concluding with the occupation of Rabaul and other bases in New Britain and New Ireland. The Navy was given responsibility for the first phase under the joint directive for operations and would naturally depend on the Marine Corps to provide the required landing force.

That force would be the 1st Marine Division, under Maj. Gen. Vandegrift, which had been formed in February 1941. Moved to New Zealand during May and June 1942 in anticipation of engaging in active operations, the 1st Marine Division was not fully trained in the ways of modern amphibious warfare. This new strike force’s prime mission prior to the war had been seen as one of mounting sea assaults against Japanese-held islands in the Central Pacific in support of the Navy in case of war with Japan.

The tactics and doctrine to carry out this mission had been set down in 1934 in the Marine Corps’ Tentative Manual of Landing Operations, the first detailed treatise ever developed on the subject. In 1938, it became official Navy doctrine and was slightly revised in 1941 to become the theoretical foundation for U.S. amphibious operations in World War II. It stressed six primary components: command functions, naval gunfire support, air support, ship-to-shore movement, securing the beachhead, and logistics.

If the theory relating to amphibious assaults by the Marine Corps was in place for a number of years before the war, proper equipment and training required to test the theory was lacking in 1942. Between 1935 and 1941 the Corps attempted to refine its new doctrine and tactics during the annual fleet landing exercises. The practical experience gained from these showed that the Marines’ mission would be hampered by shortages of transports and poor communication among ships, the transports, and troops ashore. Also, it became evident that not nearly enough landing craft, especially the new Higgins boats, were available for ship-to-shore movement of troops.

Amphibious training just before the war garnered mixed results. Between June and August 1941 at New River, North Carolina, training exercises brought to light deficiencies regarding combat loading of transports and the offloading of supplies onto the beach. The suitability of troop transports was also called into question, as was the effectiveness of naval gunfire support.

Further complicating the first U.S. sea assault of the war was the fact that only some elements of the 1st Marine Division had ever practiced the techniques of such an operation. The 5th Marine Regiment, along with the 1st Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, were the only units slated for the Guadalcanal invasion that had participated in the training exercises at New River, and the next year at Solomon’s Island, Maryland.

The rest of the assault force from the 1st Marine Division, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 1st Marine Regiment, the 11th Marine Artillery Regiment, and all the division’s logistical and support units would be engaged in a landing, possibly opposed, without any prior training. The division’s 7th Marine Regiment had been detached to Samoa prior to the move to New Zealand and would miss the initial landings on Guadalcanal. All in all, the 1st Marine Division, stripped of one of its combat regiments, broken apart and then reconstituted three separate times since early 1941, lacked the training and cohesion to assure success in the Guadalcanal operation in the summer of 1942.

“We’re Going to Rehearse at Koro”

In early July, with only three days’ notice, Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, director of the Navy’s War Plans Division, rushed to finalize the plan for the first U.S. Navy offensive thrust since the Spanish-American War of 1898. Approved by Admiral Ernest J. King, chief of naval operations, and Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Area, Turner’s plan called for the U.S. occupation of the Santa Cruz Islands, the island of Tulagi, and the “occupation of an airfield or airfield site” on the north coast of Guadalcanal, which Turner had learned was being built by the Japanese.

Raising the concern with Nimitz that the forces scheduled to conduct the operation where inadequately trained to do so, Turner stressed the need to carry out a preinvasion practice by all the land, sea, and air units that were to take part in the invasion. This would not only allow for practical experience in amphibious warfare but also provide for the inclusion of actual naval and aerial bombardment in support of the land forces. Nimitz approved, and Turner then looked for a site at which to conduct the exercise.

The place Turner came up with was the Fiji Islands, a British colony 1,100 miles east of Guadalcanal. It was considered secure from the prying eyes of the enemy, and Nimitz gave his approval, stressing that a rehearsal “was considered essential” and should be held in the six-day period beginning July 23, which would allow for two full practices.

The next step was to identify a suitable landing area for the exercise. To that end, Maj. Gen. Vandegrift dispatched his aide, Major Donald Fuller, and Captains Louis Ennis and C. Ray Scwenke to confer with the British authorities in the Fijis and to conduct air and ground reconnaissance of possible areas to be used for the rehearsals. Although Koro Island was not originally on the list of sites, it was suggested to the American team by their U.S. and English contacts in the Fijis that the island, a wedge-shaped mountainous island 100 miles northeast of Suva, might do. The survey of the site was conducted during what the officers believed to be low tide. Although their observations revealed that a large coral reef surrounded the island and it gave them cause for concern, they recommended Koro on account of the prompting of their British hosts and the lack of time they had to explore other options.

On July 15, Fuller and his fellow explorers reported to Vandegrift and Vandegrift’s new superior, Admiral Turner, to offer their recommendation. Turner, who had just arrived in the theater, had been recently selected to command the amphibious forces in the South Pacific and execute the very mission he had planned. Fuller and his assistants informed their superiors that Koro was “a most unpromising and unsuitable area.” Unfortunately, they did not have a better suggestion. Turner commented, “It doesn’t make any difference. We don’t have any time. We’re going to rehearse at Koro.”

Turner’s decision seems faulty in hindsight, but at the time he made it he had learned of facts that were throwing his schedule off track, thus limiting the time for the projected rehearsal. The July 23 rehearsal date had been based on the premise that the real invasion of Guadalcanal would take place on August 1. However, severe rains and ship-loading problems in New Zealand had prevented the 1st Marine Division from sailing from Auckland as originally envisioned. The delay threatened to jeopardize the invasion date.

To compensate, and still be able to attack Guadalcanal in the first week of August, the practice, which Turner always considered vital to the success of the real thing, was pushed back to July 28, with the invasion of Guadalcanal to take place on August 7. Further, the arrangements with the British colonial government in the Fijis had been completed, including the removal in late July of half of the population of Koro, 966 natives, from the affected zone on the island’s north shore.

Rehearsing the Landing at Guadalcanal

The four-day preinvasion exercise, extending from July 28 to July 31, was to be carried out by Turner’s Task Force 62, which included 19,000 ground troops of the 1st Marine Division in 22 transports, two fire support groups comprising cruisers and destroyers, and three fleet aircraft carriers with their complement of fighter, dive, and torpedo bomber aircraft. The naval component of the exercise totaled 72 ships. The landing zones were designated Red Beach (1,600 yards wide), Blue Beach (500 yards), and Green Beach (150 yards), with the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 5th Marine Regiment, and the 1st Marine Regiment hitting Red Beach; 1st Raider Battalion and 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, and the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment landing on Blue Beach; and the 1st Parachute Battalion disembarking on Green Beach.

On Tuesday, July 28, Vice Admiral Frank J. Fletcher, who had led the American naval forces at the Battle of the Coral Sea and who was in overall command of the assembled forces for the invasion of Guadalcanal, gave the signal for the rehearsal to begin at 9 am. The exercise was to be carried out in two phases, with the troops landing on the 28th and being recovered the following day and with the process repeated on the 30th and 31st.

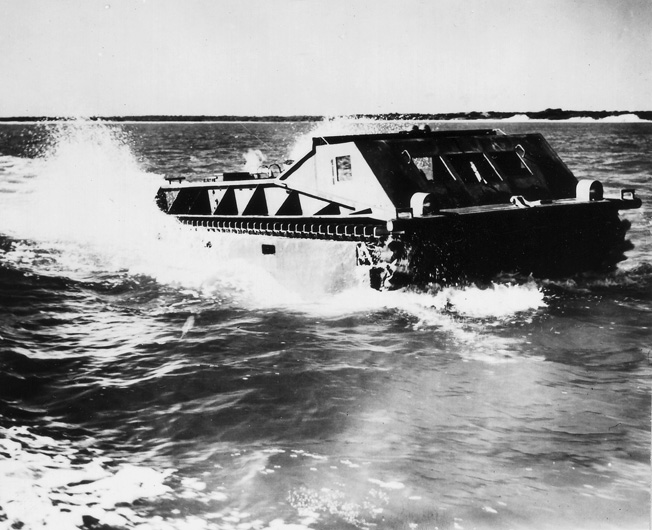

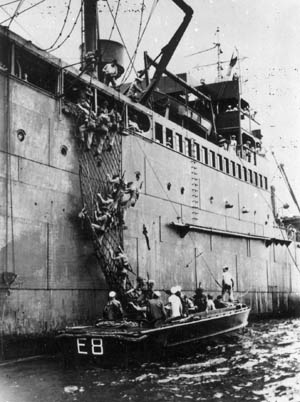

At the appointed time the rehearsal commenced with 36 wooden Higgins boats along with 30-foot X-boats and ramp boats being hoisted over the sides of the transports and lowered into the sea 8,000 yards off the north coast of Koro. Each carried a crew of three plus 36 Marine passengers, the latter weighted down with 70 pounds of equipment and arms. After moving 500 yards from the transports, the landing craft began to circle until the entire landing force was assembled for the run to shore. Soon the five waves of landing boats, with five-minute intervals between each wave, headed for the line of departure some 3,500 yards further south and about halfway between the transports and the beaches. Operation Dovetail, the first mass amphibious exercise in Navy and Marine Corps history, was on.

As the small boats reached the line of departure, the officers in charge checked their watches. The time was 2 pm. To their chagrin, they saw that the operation was already an hour and a half behind schedule. Further, it would take the Higgins boats, which traveled only 10 miles per hour, another 20 minutes to reach the shore. The top brass was displeased with the slow progress of the movement, but a far worse problem would soon reveal itself and derail the entire operation.

A Troublesome Low Tide

Unknown to the American planners, the start of the rehearsal coincided with low tide in the waters off Koro. As the landing craft carrying elements of the 5th Marines neared Red Beach, they encountered large coral formations, many two to three feet in diameter and clearly visible below the surface of the water. Loaded with men and their equipment, the draft of the Higgins boats was two feet. As they neared the shore, many of their propellers struck the coral outcroppings.

Unable or unwilling to continue, the crews stopped their forward movement about 100 yards from the shoreline and ordered their passengers to go over the side. Many Marines did and found themselves plunging into water well over their heads. Soon, hundreds were struggling to climb back on board in an attempt to avoid drowning. A few of the Higgins boats were able to elude the coral obstructions and place their charges in shallow water or on the beach itself. The scene on and near the shore was one of damaged ships and waterlogged, bewildered men.

Marines of the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment were landed no more than 50 yards from the shore. Their relief at not having to wade to the beach from a longer distance was dampened by the realization that they were not where they were supposed to be. They found themselves some 1,800 yards from their proper landing site on Red Beach. As the 3rd Battalion trudged off to where it should have landed, the follow-up troops scheduled for Red Beach (the three battalions of the 1st Marine Regiment) arrived just off shore. As they prepared to go over the side, the wave leaders received a visual message to abort the landings and return to the transports.

The boats dutifully turned around and headed back to sea. Not long after reversing course, they passed the boats carrying parts of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, and a battery of artillery from the 11th Marine Regiment going toward Red Beach. Not seeing the signal to turn back, this group landed on the beach and spent an uncomfortable night on Koro with little food, no shelter, and no communication with the outside world.

Disobedience, Confusion, and Chaos

The seascape stretching between the troop transports and Koro from 2:30 pm to 3:30 pm was one of complete chaos. The last Higgins boat did not return to the transports until after 6:30 pm. Confusion did not reign just within the waves of assault craft trying to reach the beach. Many support troops, such as those of the 11th Marine Regiment, never got to board the landing boats and leave the transports. Inadequate loading procedures and poorly planned disembarkation schedules held up the transfer of some forces from their transports to the landing craft. Before it was all sorted out, the operation had been closed down for the day.

Impetus for canceling the July 28 maneuvers at Koro was initiated by Navy Lieutenant Jack Clark of the troop transport Fuller, one of the beachmasters assigned to Red Beach and the repair officer of Transport Group 62.1. As he was approaching Red Beach with the third wave carrying the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, Clark saw the damage to the landing craft caused by the coral knobs. He saw disabled Higgins and ramp boats with hull damage below the waterline. Greatly concerned about the growing number of damaged ships, the possible depletion of his limited number of spare propellers, and their impact on the real landing at Guadalcanal, he contacted Captain P.S. Theiss on the Fuller to report the situation.

Not long after radioing Theiss, Clark noticed a launch from the task force flagship McCawley approaching the island. It quickly turned to the McCawley, and soon the signal to stop the rehearsal was received. Clark’s gloomy report from the shore to Theiss had been intercepted by the radio operator on the flagship and given to General Vandegrift and Admiral Turner. They had dispatched staff officers to assess the situation.

The launch Clark had seen moving toward the beach and then turn around had carried some of these officers. After seeing for themselves the damaged boats and disorganization of the troops on shore, they convinced Turner and Vandegrift to call a halt to day one of Operation Dovetail. Also, Turner had learned about the same time he received this recommendation that in addition to the boats that were damaged by the coral off Koro others were inoperative due to mechanical failure. On one transport alone, 12 boats could not be used.

The following day, Clark was summoned by Captain Theiss and informed that as a result of his invaluable intervention on the 28th he had been named by Turner as beachmaster for the entire Guadalcanal invasion.

While the mission on Red Beach was nearing failure, the landings on Blue Beach seemed to be going satisfactorily. The 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, and the 1st Raider Battalion had reached their destinations only about 20 minutes behind schedule. Unfortunately, many of the men disembarked 200 yards offshore and had to wade the remaining distance to land. Two hours later, the rest of the Blue Beach landing forces reached Koro, but they too were forced by the coral to go over the side and wade hundreds of yards in knee-deep water to reach shore.

At Green Beach, the 1st Parachute Battalion closed in on its objective according to plan and on time. However, as with the other beaches, especially at Nola Point, the main Green Beach landing area, the coral heads damaged propellers and boat hulls.

As evening settled on Koro, the Marines who had been scheduled to remain on the island found themselves without adequate food or shelter. With little control exerted by their officers and NCOs, the men, against standing orders, scooped up any pigs and chickens left behind by the island’s inhabitants and ransacked deserted native dwellings. Unauthorized fires to cook the captured animals blazed along Red and Blue beaches, and camp security was generally nonexistent. Even the commanding officer of the 5th Marine Regiment, Colonel Leroy Hunt, was unable to curtail the lax discipline and rowdy behavior that night on Red Beach.

“Terrible Turner”

The Marines who had landed on Koro on the night of July 28 were scheduled to be returned to their transports the following day. In addition, the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment, was to land on Green Beach and simulate an attack on a specific objective before being carried back to its transport that afternoon. However, the cancellation of the landing exercises in mid-execution on the 28th prompted Admiral Turner to revise the activities for the 29th.

Turner ordered that the morning be spent re-embarking the units of the 2nd and 5th Marines and the Raiders who had stayed on Koro the night before. After theses troops were back on their transports, elements of the 11th Marine Regiment were to take to their landing craft, move to within 2,000 yards of Red Beach, and be returned to the transports. The landing of the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines on Green Beach was cancelled. Turner’s limited maneuver of the 29th was rooted in his desire to avoid any more damage to his precious few Higgins boats.

By mid-morning, all the troops from Koro had been brought back to the waiting transports. The 11th Marines had made an uneventful trip to within 2,000 yards of the island and returned by 3:30 pm. About this time, Lieutenant Clark was making an inspection of the condition of the landing boats carried by the Fuller. Many needed new propellers, and while seeing to their replacement he was called to a meeting with Admiral Turner.

The new beachmaster of Transport Group 62.1 recalled that the conference with the Admiral on the McCawley was one of the less pleasant planning discussions he ever participated in during the war. Not surprisingly, due to the dismal performance of the day before, Turner displayed some of the personality traits that had given rise to his nickname of “Terrible Turner.” He was particularly furious about the conditions of the boats on the transports, taking the ship captains to task for the mechanical breakdown of so many of the boats during the rehearsal on the 28th. He demanded that they be repaired immediately.

Turner also sounded off about the slowness of the ship-to-shore operations. He complained that hoisting the boats for embarkation was taking far too long and that even a 50 percent reduction of the time was not good enough. He went on to demand that each transport captain significantly speed up the transfer of the Marines from ship to landing craft and report to his staff the time those vessels were lowered into the water, when each boat arrived at the line of departure, and when each wave reached the shore.

Change of Schedule

The exercise for July 30th was originally envisioned as a repeat of the landings of the 28th, with the addition of coordinated naval and aerial bombardment using live ammunition. Turner modified this scheme for the 30th, and instead of actual landings by his men, waves of landing craft carrying Marines would move to within 2,000 yards of the shore and then return to the transports. Green Beach was stricken from the list of missions for the 30th.

Shore bombardment was to be carried out off Red Beach by four destroyers and three cruisers. Off Blue Beach two destroyers and one cruiser were to conduct live fire, while at Green Beach five minesweepers were ordered to shoot at Nola Point. Nearly simultaneously, 32 fighters and 51 dive bombers from the three aircraft carriers would conduct strafing and dive bombing runs against Nola Point and the north shore. Flight operations commenced at 10 am on the 30th and were deemed a great success by the carrier commanders as their planes, according to a war correspondent on the carrier Enterprise, hit their targets “blasting coral on the beaches and ploughing up the sand.” The performance of the naval gunfire, however, proved to be more problematic.

At 8:55 am, Turner changed H-hour for the start of the naval fire component of the exercise. All went well, even with the change of H-hour to 10:30 am, with the coordinated shore bombardment and landing approach at Blue Beach. While the landing boats went to within 2,000 yards of Koro and then returned to their transports, the Navy fired 123 rounds at the island.

Mistaken Landing on Red Beach

Things did not go as well on Red Beach.

Captain Theiss of the Fuller did not receive the change of the start time for the exercise and did not realize that troops were not to land on Red Beach. As a result, by 10 am the first wave of Marines was clambering ashore on Red Beach. As the second wave approached Koro, the destroyer USS Ellet, serving as the control ship for the amphibious practice on Red Beach, steamed in from the ocean and ran dangerously close to the shore. She had been given the unenviable mission of warning the errant Marines to get off the island as soon as possible because the Red Beach shore bombardment was about to commence. The second-wave commander got the message from the Ellet and ordered his force to turn back. Sailing parallel to the shore and using hand signals and voice, he got the first-wave boats to take men off the beach and back out to sea. But many men could not be brought off and were left stranded on Koro.

With only minutes to go before the naval bombardment was to begin, the ships slated to fire on Red Beach received notice to postpone the operation until mid-afternoon when it was assumed the Marines still on Koro could be evacuated. Further complicating the situation was that some first wave Red Beach landing craft had not reached the 2,000-yard line of departure until 12:30 pm, with the second through fifth waves not gaining that position until 1 pm. This tardiness not only allowed for the possibility that some troops might go all the way to Koro, but that those wandering boats might get in the path of the bombardment groups. By late afternoon the mission to conduct naval fire on Red Beach was suspended when it was acknowledged that the Marines could not be extricated from there until the next day.

By 5 pm on July 31, all the Marines who had been sent over the side the morning before and marooned on Koro were back on their transports. Some had more trouble doing so than others. A number of boats holding units of the 11th and 5th Marines had to catch up with their parent transports, which were already leaving the area. One Marine in a Higgins boat trying to overtake its transport as the latter stood out to sea later remarked, “Christ, we felt that the Navy was in such a hurry to get out of there they would have left their grandmothers behind if it would have allowed them to go faster.”

The Koro Rehearsal: “A Complete Bust”

Operation Dovetail was a disappointment to the commanders involved. Lt. Col. Sam Griffith, 1st Raider Battalion executive officer, recalled that after its conclusion it was the only time he ever saw Vandegrift despondent. In his autobiography, the general wrote, “I shuddered to think what would happen if those beaches turned out to have been defended in strength.” In 1948, he termed the Koro rehearsal “a complete bust.” At a lower level, Captain William Hawkins, commander of Company B, 1st Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, summed up the feelings of many fellow Marines who took part in the practice at Koro and later in the initial landing at Guadalcanal when he recorded, “We would have been slaughtered” if Koro had been in Japanese hands.

The rehearsal for the Guadalcanal landing was hampered first and foremost by the poor choice of coral-ringed Koro. For this, the blame falls squarely on Admiral Turner; he made the final choice. The second major cause for the less-than-stellar performance at Koro was the poor mechanical condition of many of the landing craft engines. Further, it was fortunate that only a few Higgins and ramp boats were completely destroyed at Koro and that the damaged craft were put back in working order prior to the real landing on Guadalcanal.

Ship-to-shore operations proved to be too slow, including the transfer of troops from transports to landing craft, and the inexperience of the landing craft crews slowed the drive to the line of departure. These factors combined to cause a delay of at least three hours.

Operation Dovetail raised the issue that U.S. Navy attempts to effectively coordinate naval gunfire and air support with amphibious operations were in an elementary state in 1942. Poor reconnaissance failed to pinpoint targets, adversely affecting American air strikes and naval bombardment at Guadalcanal, and this was apparent during the rehearsal at Koro.

On the positive side, some lessons were learned from the otherwise faulty Koro rehearsal. Flawed as it was, the exercise provided invaluable experience in ship-to-shore embarkation for many Marine company and battalion officers who had never participated in such a mission before. It also helped to eliminate some of the problems resulting from the need for better communication to achieve a successful coordinated land-sea-air operation.

Further, the loading and offloading of supplies onto ships and then onto the invasion beach was improved between the conclusion of Operation Dovetail and the start of the landings at Guadalcanal. Last, and of great importance, a system was created (first developed on July 30 at Koro) that pooled all the landing craft to prevent the delayed arrival of the assault waves due to the breakdown or absence of these essential vessels.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments