By Chuck Lyons

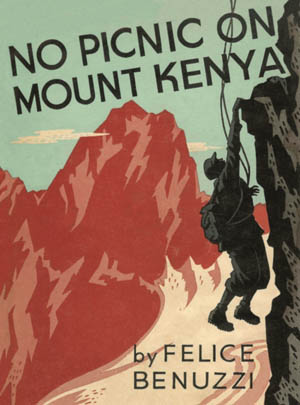

Felice Benuzzi’s part in the war may have been a small one, but his story is one of the oddest to come out of World War II. An Italian diplomat, Benuzzi had been a British prisoner of war for two years and, feeling crushed by the tedium of the African prison camp where he was confined, decided to overcome his own boredom by taking action. Along with two fellow prisoners, he escaped in January 1943, leaving a note for the camp commandant promising that they would return.

They did.

However, it was only after he and the other two men had climbed the 17,000-foot Mount. Kenya that loomed above the camp, a peak Benuzzi described as “an ethereal mountain emerging from a tossing sea of clouds.”

Felice Benuzzi was born in Vienna, Austria, on November 16, 1910, and grew up in Trieste, mountaineering in the Julian Alps and Dolomites. After studing law at Rome University, he entered the Italian Colonial Service in 1938 and was sent to Ethiopia as a colonial official. But Mussolini’s dream of an African empire was short lived. Benuzzi was stationed in Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, when a British Army offensive moved into East Africa. By 1941, he was a prisoner of war interned in British POW Camp 354 at the foot of Mount Kenya and just south of the equator.

The life of the camp bored him.

“The sole activity for this host of people was to wander around the camp, walking around and talking to one another,” Benuzzi said in the 1952 book he wrote about the camp and the mountain, No Picnic on Mt. Kenya.

Two experiences changed his outlook.

First Impressions at Camp 354

It was rainy season when he first arrived at Camp 354, and the mountain was hidden by rain and clouds. One morning another prisoner woke him and pulled him outside to see the mountain, which was briefly visible through the clouds. Though a mountaineer, it was the first 17,000-foot peak Benuzzi had ever seen, and he wrote that he remained “spell-bound” for hours afterward.

“I had definitely fallen in love,” he said.

The first European to see Mt. Kenya, the second highest mountain in Africa, was a German missionary in 1849. It was first scaled in 1899. The mountain is topped with several peaks, the highest of which, Batian, is at 17,057 feet. Around its base lay fertile farmland cut out of the tropical forests, then it rose through jungle and belts of bamboo, through timberline forest with relatively small trees, lichens, and moss, then heath and grassland, followed by glaciers and snowfields.

The “ethereal mountain” beckoned Benuzzi.

“A Strange Sense of Envy”

Benuzzi’s second transforming experience happened a few months later when he was heading back to his barracks one night from a chess game. He heard hammering from inside one of the camp buildings and realized someone was busy working on a project.

“A strange sense of envy crept into my mind,” he wrote. “That prisoner had set himself a task, whatever it was. For him the future existed, [and] he had found a remedy for captivity.”

To escape from the boredom he felt, Benuzzi realized he had to do the same thing.

“To break the monotony, I need only to start taking risks again,” he wrote.

And the risk he would take was to climb the mountain he had fallen in love with.

He began by writing to his family in Italy and, without saying why, asking that they send him his boots and some warm woolen clothing. He quit smoking and used his allotted cigarettes, the general currency of the camp, to buy other items he needed. He sold whatever of his personal belongings he could to raise additional capital, scoured camp trash heaps for usable items, and was able to locate a homemade Italian flag hidden in the camp. He hoarded chocolate, dried fruit, and crackers from the food parcels he received, had ice axes fashioned from hammers stolen from a workshop, and created crampons rigged from odds and ends salvaged from the trash heaps. For maps, he had only sketches he had made of the mountain and the label from a food can with a picture of Mt. Kenya that showed a different side of it. He undid the netting of a bunk bed and twisted it into a quarter-inch, 35-foot-long rope.

He also started recruiting. One recruit would need to be a mountaineer and would accompany Benuzzi on his final scramble to the peak. But the other man would be able to stay at the base camp while the final ascent was taking place. His main job would be to help with the night watches while the party worked its way up through the tropical forests, bamboo thickets, and the like on its way to their final camp. They were especially leery of the rhinoceroses that were known to roam the lower parts of the mountain.

Benuzzi Begins His Recruitment

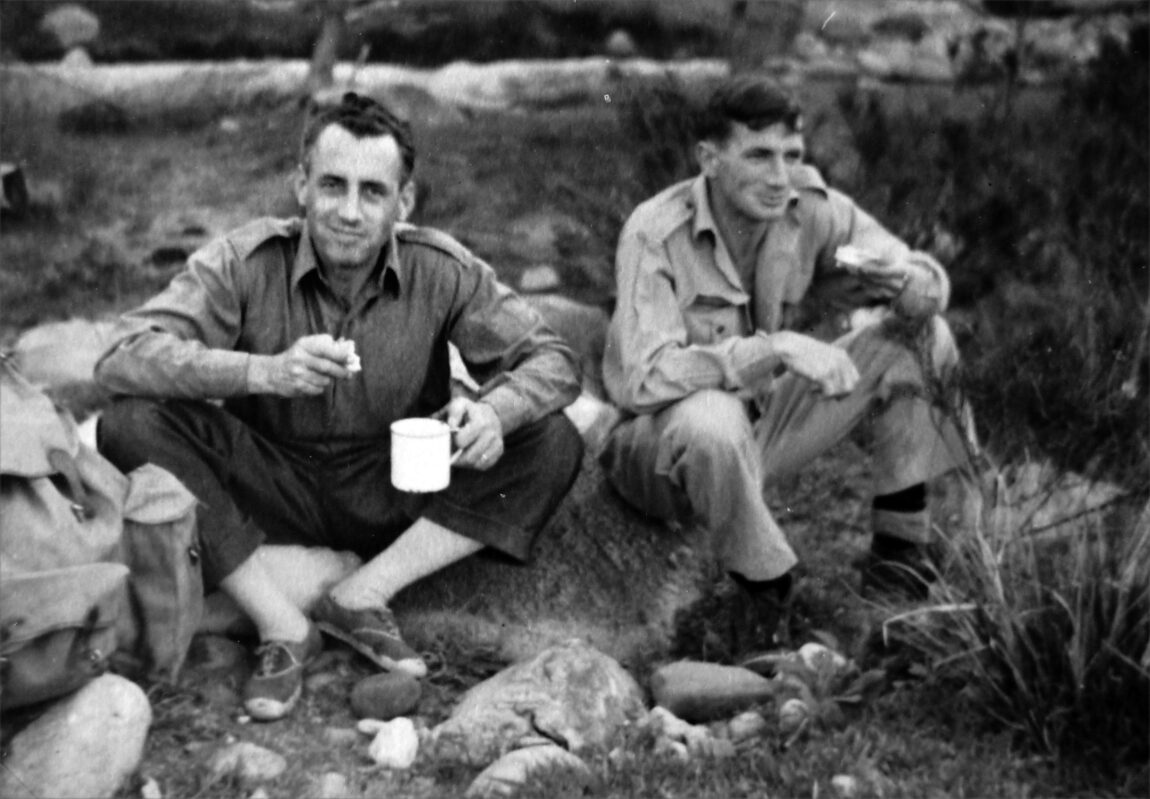

Benuzzi recruited his bunk mate, Giovanni Balletto, a doctor and mountaineer, and for the third man found Enzo Barsotti, who had never climbed a mountain in his life.

The reason why he decided on Barsotti, Benuzzi said, “was because he was universally thought to be as mad as a hatter, and mad people were what we needed.”

During this time of preparation, Benuzzi wrote, he was often bedeviled by second thoughts. “There were occasions when the thought of our impending adventure made me frightened. Sometimes, I thought what it would be like lying out in the dark wet forest, dead tired, exhausted by hunger, drenched to the bone, in imminent danger of being attacked by wild beasts, That prospect I compared with the warm blankets in my bunk, the familiar oil-lamp and the good book I was now preparing to read.”

When such thoughts arose, he wrote, he had only to look around the camp,

How To Get Out of the Camp?

“Listening to the platitudes of prisoners talking, I sometimes felt that I could not understand them any more. At other times I felt only pity that they should be content to endure this stagnating life without having in mind a project like ours.”

With the team recruited and equipment prepared, the men still had one problem left: how to get out of the camp.

Earlier in their stay, camp authorities had given Balletto a plot in the camp garden where he could grow tomatoes and other vegetables and on which he had built a small tool shed. Perhaps they could escape through the garden. The three men gradually moved their equipment and supplies into the garden plot and hid everything among the tomato plants. Since it was the dry season, they had no fear of a sudden storm drenching their supplies.

Access to the garden was through a locked gate that was opened for any prisoner displaying a “garden pass” and seeking to go to work in his plot. But Benuzzi and his men would need to get into the garden at night, and except for Balletto they had no passes.

They needed a key to the gate.

“The Sentry Did Not Move… But Neither Did the Key”

After several failed attempts to get hold of the key, Benuzzi finally found it carelessly left on the British compound officer’s desk and was able to make several impressions in a piece of tar. A prisoner mechanic then cut a key based on those impressions.

Benuzzi leaned against the gate on a quiet Sunday afternoon and, watching a nearby sentry, slipped the new key into the lock. It did not work.

“The sentry did not move,” he wrote, “but neither did the key.”

Several adjustments to the key were made, but all failed. It was not until Benuzzi had what he called “the brilliant idea of oiling the key” that he “felt the blissful satisfaction of the click of a complete revolution.”

They were in, and the breakout was scheduled for January 24, 1943.

About noon that day while the prisoners and many of their guards were having lunch, a confederate dressed like the camp commander approached the gate with three prisoners carrying shovels. He opened the gate, the prisoners entered the garden, and he closed the gate, locked it, and walked off. Benuzzi, Balletto, and Barsotti were in the garden. They huddled inside the small tool shed and waited for evening when they would try to get out of the garden past the sentry said to guard the outer perimeter.

When darkness fell, fortunately coupled with a cloudy sky, the three men easily passed out of the garden without seeing any sentry, crossed the camp perimeter, crossed the rail line where they were silhouetted in the light of a passing train, and reached the shelter of some thorn bushes on the other side. They took a break there, and as the sky began to clear “the glacier-clad Mount Kenya was seen clear-cut against the starry background.”

Breaking Out

They then worked their way to the main road, where a passing military car almost spotted them, and crossed quickly into a dark clearing on the other side and under some more thorn trees. At times, they walked backward to leave footprints that would further confuse any pursuers.

They had escaped the camp.

Over the next 18 days, they traveled first at night and then during the day past a logging camp and through the tropical forest, where they encountered a bull elephant through the bamboo groves and the grassland. They crossed glaciers and snow fields and established a base camp at 14,000 feet. From there Benuzzi and Balletto attempted to scale Buitan only to be beaten back by a heavy snowstorm. They returned to base camp, took a day of rest, and then attempted Lenana, at 16,355 feet the third highest summit on the mountain.

This time they made it, and they planted the camp’s homemade flag in a cairn at the top and ran four strings from the small flagpole, anchoring them with rocks to hold the flag in the wind.

“It was a grand sight indeed,” Benuzzi wrote.

They also left a sealed brandy bottle with a note inside listing their names.

The two men returned to their base camp, and the next day, with rations running dangerously low, began to descend the mountain. Eighteen days after leaving the Camp 354, they made it back to the road and the rail line where, tired, very hungry, and afraid they would be shot at if they were spotted, they fastened all their loose gear to prevent noise and began crawling back toward the camp garden.

Prisoners Again

In the darkness, they were not seen by any sentry and slipped back inside as easily as they had slipped out.

“We were safe,” Benuzzi wrote, “but prisoners again.”

The men worked their way back to Balletto’s tool shed and began to search in the dark for the food and water they had arranged for friends to leave. They found nothing. Later they learned that every time their friends left supplies those supplies had disappeared by the next day. Finally, their friends stopped leaving anything. In the morning, after a long and hungry night, the three adventurers slipped out of their hiding place, mingled with other prisoners in the garden, and finally walked back into the camp with a working party and gratefully ate lunch. They skipped evening roll call, slept in their own bunks, and in the morning reported to the British compound officer.

The men worked their way back to Balletto’s tool shed and began to search in the dark for the food and water they had arranged for friends to leave. They found nothing. Later they learned that every time their friends left supplies those supplies had disappeared by the next day. Finally, their friends stopped leaving anything. In the morning, after a long and hungry night, the three adventurers slipped out of their hiding place, mingled with other prisoners in the garden, and finally walked back into the camp with a working party and gratefully ate lunch. They skipped evening roll call, slept in their own bunks, and in the morning reported to the British compound officer.

They were carefully searched and put into cells, sentenced to serve 28 days for their prank. They only served seven days, however.

“[The] Camp Commandant was very kind to us and had, as he put it, ‘appreciated our sporting effort,’” Benuzzi wrote.

Their feat became public knowledge a few days after they returned to camp when a party of British climbers found the Italian flag on Lenana.

Repatriated in August 1946, Felice Benuzzi entered the Italian diplomatic service in 1948, serving in Paris, Brisbane, Karachi, Canberra, West Berlin, and as head of the Italian delegation at the United Nations. In 1973, he was appointed ambassador to Uruguay and lived in Montevideo. Benuzzi retired to Rome, serving in retirement as head of the Italian delegation for the Antarctic.

He died in Rome in July 1988.

Just amazing.