By Mike Phifer

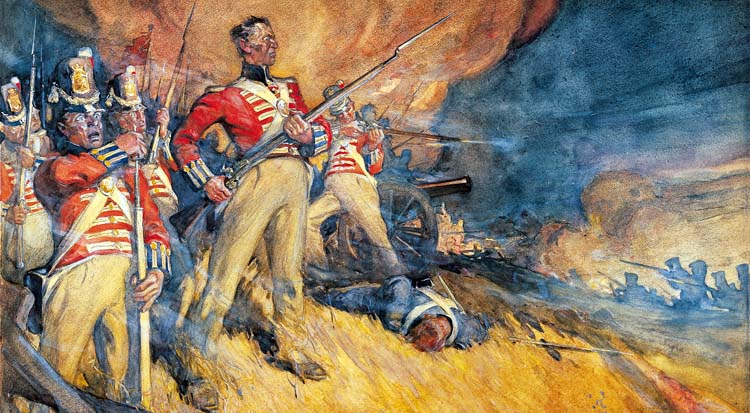

The crash of musketry in the early hours of August 15, 1814, quickly caught the attention of Captain Nathan Towson. Commanding an American battery on Snake Hill at the southern end of the expanded fortifications at Old Fort Erie, Towson could tell by the several volleys that his pickets had fired that the British were coming his way. All night, the American troops had been on high alert for an expected redcoat attack. As a precaution, Towson had ordered his gunners to sleep near their six-pounders. The Americans had loaded their guns with double shot. They stood ready by their guns waiting for Towson to give the order to fire.

“This was to me the most perplexing moment of my military life,” recalled Towson. The pickets under 19-year-old Lieutenant William Belknap of the 23rd Infantry fell back in the face of unrelenting pressure by the British. Unfortunately, Belknap and his pickets blocked Towson’s line of fire. “Every minute’s delay in firing jeopardized the whole army,” Towson wrote. Nevertheless, they initially held their fire in an attempt to avoid cutting down Belknap’s gallant pickets.

Deciding that he could wait no longer even though Belknap and his men were not completely in the clear, Towson gave the order for his men to touch off three of their guns. Orange flames spewed from the barrels. Towson could only hope he had not killed too many of the pickets. The British assault on Old Fort Erie was under way.

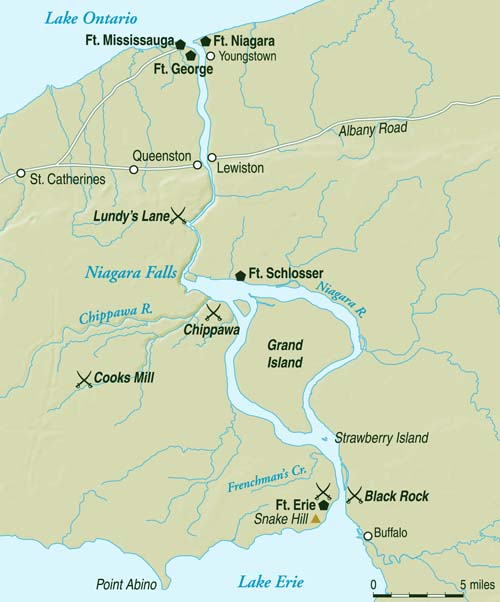

Back at the beginning of July, Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown’s Left Division of the American Army had crossed the Niagara River and invaded Upper Canada (modern-day Ontario). He intended to seize control of the critical Niagara Peninsula and push to the head of Lake Ontario. From that location, Brown wanted to turn east and capture York. In the same thrust, he might also secure Kingston.

The British Royal Navy’s base of operations in the region was situated at Kingston. It was a vital transshipment point in a long British supply line. Whether General Brown’s operation was successful, though, would depend on the degree of naval support furnished by the American fleet on Lake Ontario.

Brown’s army secured a clear victory at Chippawa River over Maj. Gen. Phineas Riall’s British army on July 5. Yet supply shortages and a lack of naval support hampered his other offensive plans. Reacting to news that the British were marching against his supply line, Brown attacked a reinforced British army at Lundy’s Lane on July 25.

During the engagement, the Americans suffered 860 casualties, one of whom was a severely wounded Brown. Command of the battered Left Division devolved to Brig. Gen. Eleazer Ripley. As he was evacuated, Brown ordered Ripley to withdraw and regroup. His orders were to fall back to the American camp at Chippawa. With 60 wagon loads of wounded, the Americans withdrew into the darkness toward Chippawa.

The following morning, Ripley led the bulk of his army back to Lundy’s Lane. He ordered two companies to scout the British position. Their officers reported that the redcoats outnumbered the Americans; furthermore, the British held the high ground. After consulting with his senior officers, Ripley decided another battle was unwise, given that his troops were in no condition to fight. He would have preferred to withdraw back across the Niagara River into New York, but most of his officers rejected the idea. Instead, the army would fall back to Fort Erie. Lundy’s Lane had been a tactical draw, but given that the American invasion had come to an abrupt end, it was a strategic victory for the British.

Fort Erie (sometimes called “Old Fort Erie”) was situated on the west side of the1 Niagara River opposite Buffalo, New York, at the south end of the Niagara Peninsula. The British had established the fort in 1764 to help secure their supply line between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. The fort saw action in the American Revolution. The British began building a stronger fort, which was made from Onondaga flintstone, in 1803 on the heights behind the site of the original fort. It was never fully completed, through, owing to a lack of funds. Nevertheless, the British were able improve and extend the fortification’s earthworks before the war began.

The Left Division, with its 2,100 men, retreated to Fort Erie after burning the captured British works at Chippawa. Meanwhile, Ripley crossed the Niagara River to talk with Brown in Buffalo. Ripley informed Brown that he believed the army should be withdrawn from Upper Canada. If they were not withdrawn, he would not be responsible for their fate. Ripley’s fatalistic attitude angered Brown. He directed Ripley to strengthen the fort’s defenses. He also told him that under no conditions was he to surrender the strategic fort to the British.

The troops of the British Right Division were as battered as their American opponents. Having suffered 880 casualties at Lundy’s Lane, the British and Canadian troops were exhausted and incapable of immediate pursuit. Their commander, Lt. Gen. Gordon Drummond, who had been wounded at Lundy’s Lane, remained on duty in the field. He dispatched his vanguard, composed of Indians and the 19th Light Dragoons, on July 28 to reconnoiter the American position. Fearing the American fleet on Lake Ontario might attack his supply line, he sent detachments to reinforce the British-held Fort Niagara and Fort George, which guarded the east and west sides, respectively, of the mouth of the Niagara River. The main force set out south to catch up with the vanguard several days later.

By August 1 Drummond’s 3,500 British troops were six miles north of Fort Erie. The following night, Drummond dispatched Lt. Col. John Tucker with a force of 580 men across the Niagara River to destroy the U.S. military depots at Black Rock and Buffalo, New York. The force consisted of the 41st Regiment, the light companies of the 89th and 100th regiments, the flank companies of the 104th Regiment, and a Royal Artillery detachment. With the destruction of these depots, Drummond hoped the Americans would be forced to evacuate Fort Erie or come out and fight.

Tucker’s detachment crossed the Niagara River around midnight, but it would be about 4:30 a.m. on August 3 before they got moving. The defenders of Black Rock, the 1st Rifle Regiment under Major Lodowick Morgan, had spotted the British across the river the day before and suspected a possible raid on the depot. To counter this, they took up position two miles north of Black Rock at Conjocta Creek. Morgan’s men ripped up the planks of the bridge spanning the creek to impede British passage over the waterway. They then constructed breastworks and awaited the enemy’s arrival.

Tucker, who had not sent out an advance guard, walked right into the waiting rifles of the Americans. The 41st spearheaded the attack, but the Americans drove it back with a vicious hail of rifle fire. The redcoats rallied and advanced again. This time, though, they were reinforced with the rest of Tucker’s command. The American fire picked off any enemy soldiers who approached the bridge. Tucker withdrew his troops a short distance. At that point, the two sides traded fire for nearly three hours. In the end, the British withdrew altogether. Tucker’s force had suffered 44 casualties, while Morgan suffered two killed and 10 wounded. Tucker blamed his men for the failed attempt at Black Rock. Drummond was deeply irritated by the repulse, for it meant that he would have to besiege Fort Erie.

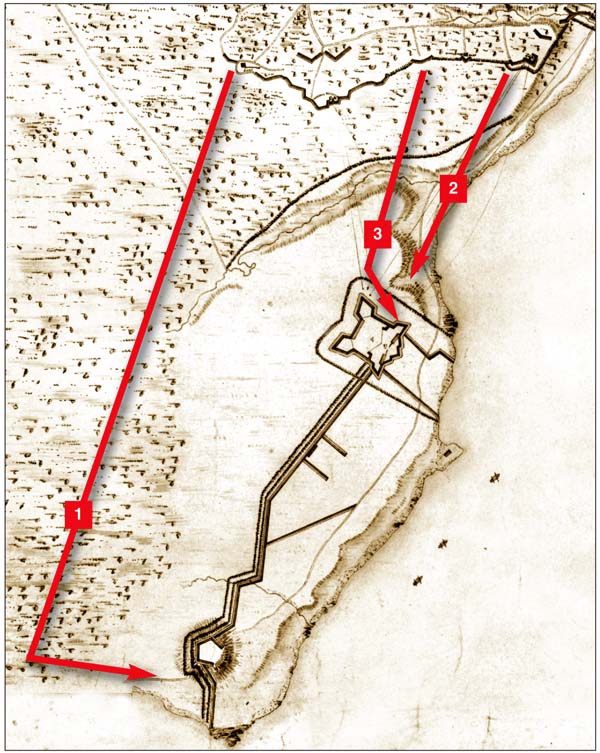

Since their arrival at Fort Erie, the Americans had worked around the clock to improve their fortifications. The American constructed not only earthworks, but also a battery that they named Douglass’s Battery, in honor of Lieutenant David Douglass, of the engineers who had laid out the improved defenses. The Americans anchored the new set of earthworks to the right of the fort on Lake Erie. They also built another stretch of earthworks atop a sand mound 800 yards to the south of Snake Hill. In front of the earthworks were ditches, and beyond that was an abatis, a formidable obstacle consisting of the branches of trees laid in a row with their sharpened tops pointing outwards towards the attacking enemy. As a final measure, the Americans felled trees for 300 yards around their position in order to have a clear field of fire.

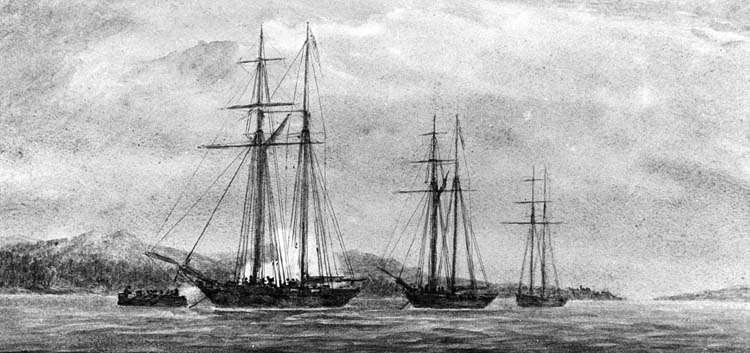

The stone fort bristled with 18 guns. In addition, they could rely on artillery support from guns positioned across the Niagara River at Black Rock, as well as three armed schooners anchored near the fort. The British were fully aware of the difficulty in capturing the fort with its improved defenses. The American-held fort was “an ugly customer,” said Lieutenant John Le Couteur of the 104th Regiment.

As darkness fell on the night of August 5, the British began constructing a battery north of the fort. Unfortunately for the British, Drummond’s engineers were some of the least skilled and experienced in the British army. “Any man who the Duke of Wellington deemed unfit for the Iberian Peninsula was considered as quite good enough for the Canadian market, and in nothing was this more conspicuous than in the Engineer Department,” said William Dunlop, a surgeon assigned to the 89th Regiment.

Hindered by the lack of tools, the British troops constructing Battery One had to contend with harassing fire from the Black Rock battery and the schooners. To protect themselves, they built an epaulement, which was an earthen parapet to protect troops from flanking fire. The British completed Battery One by August 11. They also finished construction of a trench that would lead to another battery that had yet to be established.

While work on the battery was underway, skirmishing raged back and forth as the Americans attempted to harass the construction of the battery. In one of these fierce little fights on August 12 Major Morgan was killed. The British felled the trees in front of Battery One that night, thus unveiling a formidable array of guns at first daylight. The battery boasted three 24-pounder long guns, a 24-pounder carronade, and an 8-inch mortar.

The fighting was not confined to land. Captain Alexander Dobbs of the Royal Navy, with 75 sailors and marines, had received orders to destroy the trio of American schooners. With the assistance of local Canadian militia, the British assault force portaged a gig and five bateaux by wagon to Lake Erie. When they arrived at the shore, the sailors and marines quietly launched the boat and rowed toward the enemy ships on the night of August 12. They quickly captured two of the schooners and sailed them north to the Chippawa River. The naval sortie understandably boosted British morale.

The British Battery One opened fire the following day, but it quickly became apparent that it was situated too far away to do serious damage to the fort. Dunlop estimated that only one-tenth of the gunners’ shot was striking the fort; even so, the shots that struck home inflicted casualties. A British mortar shell fired on August 14 struck the fort’s magazine producing a large explosion. The British also began firing heated shot at the last American schooner, thereby forcing it to move off. Brig. Gen. Edmund Gaines, whom Brown ordered on August 4 to replace Ripley as the commander of Fort Erie, believed the British were planning a follow-up assault. His instincts proved correct.

Drummond feared he did not have enough supplies for a long siege, as the American fleet anchored off the Niagara River interfered with his supply line from Kingston. Instead of coming directly across the lake, Drummond’s supplies went by a circuitous route, being loaded onto bateaux that made their way along the Lake Ontario shore. Drummond had no luck preventing the Americans from receiving supplies and reinforcements by water across the river from Buffalo. Because of this, British hopes of starving out the defenders were dashed. Believing the Americans could muster only 1,500 men at Fort Erie, Drummond made preparations for a night assault against the fort. But he had underestimated the garrison’s size. As a result of the reinforcements from New York, Gaines had upwards of 2,800 men with which to defend the fort.

The planned British assault involved three columns. Lt. Col. Victor Fischer would lead the right column of 1,800 men in an attack against Snake Hill. The right column was composed of soldiers from his unit, the De Watteville Regiment of Swiss mercenaries, the 8th Regiment, light companies from the 89th and 100th Regiments, and a small detachment from the Royal Artillery.

Lt. Col. William Drummond’s center column would assault the fort. Drummond, who was a distant relative of the British commander, commanded 340 men drawn from the flank companies of the 41st and 104th regiments, sailors, and marines, and a detachment from the Royal Artillery.

Colonel Hercules Scott commanded the left column of 880 men. His orders were to storm Douglass’ Battery. His troops came from his 103rd Regiment and the flank companies of the 1st Regiment. Tucker commanded a small reserve. As for the Indians, they were to create a diversion. The various elements were to attack at 2:00 a.m. on August 15.

Fischer’s column moved out in the late afternoon of August 14. His men tramped through the forest heading southwest to get into position for the assault. Drummond did not have a high regard for the Swiss troops of Fischer’s command. To deter desertion, he halted the column periodically for roll call. Fischer ordered all of his troops to remove the flints from their muskets so that when they stormed Snake Hill there would not be any accidental discharges that might alert the enemy that they were coming.

The operation did not get off to a good start, as the Indians were late in creating their diversion. Some of Fischer’s men carried scaling ladders to enable them to get over the walls at Snake Hill. The column ran headlong into Belknap’s pickets. The pickets opened fire on the British, thereby alerting Towson’s battery and the 21st U.S. Infantry defending Snake Hill.

Although one of his men was killed and a few wounded, most of Belknap’s men survived when three of Towson’s guns opened fire. This was because Towson’s Snake Hill battery was 20 feet higher than the retreating pickets, and therefore most of Towson’s shots went over their heads. Bleeding from a bayonet wound in his backside, Belknap was the last man through the gap in the abattis.

Most of Fischer’s troops following Belknap struggled through the abattis while taking heavy fire. With no flints in their muskets, they could not fire back. The troops who managed to make it to the walls discovered that their scaling ladders were too short. The American soldiers poured a vicious fire into the floundering enemy troops. The devastating fire drove them off. Simultaneously, a forlorn hope formed as Fischer’s light troops waded into the water in a desperate attempt to gain entry to Snake Hill from the rear. Two companies of American troops stopped their attack cold with a blistering fire.

The attack was not going much better for the other British columns. Colonel Scott’s troops did not move forward until 3:00 a.m. They quickly came under artillery fire from Douglass’s Battery. American musket fire added to their misery. After two heroic attempts, they were still 50 yards from the abattis. This was as far as they got. The British troops withdrew having suffered heavy casualties. Scott died almost instantly from a bullet to the head. Some of the troops in his left column shifted to the center, where they joined Drummond’s assault.

The defenders of Fort Erie had repulsed two charges by Drummond’s men. On the third attempt, though, the British managed to successfully scale the stone wall surrounding the northeast bastion, where the Americans had positioned four guns. “No quarter!” the attackers shouted as they began to bayonet the American artillerymen. Some of the American artillerymen managed to escape. Having cleared the bastion, the assault party found that it could go no further. The only exit from the bastion was swept by American fire coming from the stone barracks opposite the bastion. The Americans counterattacked in an effort to retake the bastion, but their hasty assault failed. Lt. Col. Drummond was slain in the vicious fighting. Both he and Scott had premonitions that they would not survive the risky attack.

In an attempt to break the deadlock, a Royal Artillery officer had one of the captured guns turned toward the Americans and fired. A spark from the cannon’s muzzle blast fell through a crack in the wooden flooring and ignited the gunpowder magazine located below the bastion.

The resulting explosion was horrendous. Mangled bodies, chunks of stone, and shards of timber were hurled 200 yards in the air. The explosion killed a significant portion of the attacking force. The British and Canadian soldiers who survived the blast retreated to their lines. The whole operation was a bloody disaster for Lt. Gen. Drummond. The British lost 900 men, while the Americans lost just 79. Drummond was quick to blame the failed assault on the De Watteville Regiment. In so doing, he overlooked the fact that the scaling ladders were too short. Moreover, he failed to take responsibility for the clear mistake he had made by ordering the men to remove their flints to prevent an accidental discharge.

Both sides tended to the wounded, most of who were British soldiers. The Americans established two field hospitals. After they received treatment, the wounded were sent across the Niagara River for further treatment in New York. Many of the British dead were buried in a mass grave, while others ended up in the Niagara River.

Despite the setback, Drummond continued the siege. On the night of August 24, the British began building Battery Two, 300 yards southwest of Battery One. It was 700 yards from Fort Erie, which was about 400 yards closer than Battery One. American troops launched an attack against the battery the following day. The British pickets managed to repulse the attackers, but several dozen of their men were killed and wounded in the fierce firefight. Skirmishing continued on a regular basis, causing casualties to mount.

The British completed Battery Two four days later. The battery comprised two 18-pounders, a 24-pounder carronade, and an 8-inch howitzer. When the guns opened fire on the Americans the following day, the artillerists realized that the battery site had been poorly laid out. A rise of ground hindered the battery’s view of the fort. This greatly reduced its effectiveness.

Drummond’s weakened army was reinforced when redcoats from the 6th and 82nd regiments arrived to bolster his numbers. Yet his supply problems persisted. The redcoats, who lacked tents, suffered in the wet conditions brought about by periodic rain. “The troops sheltered themselves under some branches of trees that only collected the scattered drops of rain, and sent them down in a stream on the head of the inhabitants, and as it rained incessantly for two months, neither clothes nor bedding could be kept dry,” wrote surgeon Dunlop. Not all suffered, though. The Canadian troops, who had a knack for woodcraft, built themselves tight shanties from felled wood.

The Americans defending Fort Erie also suffered from a shortage of supplies; in particular, they lacked good clothing and footwear. The inclement weather damaged their food stores, some of which were stored outside because the storehouse was not large enough to accommodate the provisions of such a large force. Despite all this, the Americans continued to strengthen their position.

The British began work on Battery Three, located 350 yards west of the second battery. Battery Three was just 300 yards away from the fort. The third battery, which was completed on September 4, held a 24-pounder, two 18-pounders, and an 8-inch mortar. It was not scheduled to begin firing for a couple days. The other batteries, though, lobbed shot, shell, and rockets at the American position. The British artillerists made a special point of firing on American troops repairing the fort and earthworks.

An exploding shell seriously injured Brig. Gen. Gaines on August 28. Command of the fort devolved to Brig. Gen. James Miller. But Miller would not command the fort for very long. Although not fully recovered from his wounds, Brown returned to Fort Erie in early September.

On September 4, 140 men under the command of Lt. Col. Joseph Willcocks sortied from Fort Erie to attack the new battery. Although of Irish birth, Willcocks had lived in Upper Canada for a number of years, even serving in the Legislative Assembly. He defected to the American side in 1813 and raised a unit of Upper Canadians that he called the Canadian Volunteers. The sortie at Battery 3 raged for six hours, until a rainstorm ended the fight. After the Americans fell back, celebration swept through the British and Canadian camp when the enemy soldiers learned that Willcocks, whom they viewed as a traitor, had been killed in the action.

Drummond had planned for Battery Three go into action on September 6, but he changed his mind as his artillery crews began to run low on ammunition. He issued orders for Battery Three to stay silent until the army received a fresh supply of artillery shells. Although he initially planned to launch another attack once Battery Three became operational, he began contemplating a withdrawal in early September. It was not just the ammunition shortage that troubled him; Drummond believed his batteries were having little effect on the American defenses.

Furthermore, Drummond feared that the Americans might attempt to land troops behind Drummond’s force. Drummond’s second-in-command, Brig. Gen. De Watteville, who arrived at the besieger’s camp on September 1, advised the British commander to retreat after surveying the situation. Drummond agreed and ordered fatigue parties to begin removing the guns from his batteries.

As Drummond suspected, Brown was indeed planning a major sortie. Brown was deeply concerned about the threat that sustained fire from Battery Three posed to the fort. He therefore ordered Brig. Gen. Peter Porter, who commanded a New York militia brigade, to bring his best regiments to Fort Erie. Fifteen hundred troops began crossing to Fort Erie on three consecutive nights beginning September 8. On the first evening, Brown met with his senior officers to discuss his plans for attacking Battery Three.

The reaction of his officers disappointed Brown. Most of them wanted to wait for the reinforcements that they knew were on their way to assist them. Although Brown had been out of action since August, he had been doing his best to get additional troops for his Left Division. But the American senior command had more pressing concerns than Fort Erie, such as protecting the nation’s capital. Having defeated the Americans at Bladensburg, Maryland, on August 24, British Maj. Gen. Robert Ross led his victorious troops on a raid against Washington. When they reached the American capital later that day, they burned the U.S. Capitol, White House, and various other government buildings.

The Americans also learned that 10,000 British veterans from the Napoleonic Wars in Europe had arrived in Lower Canada. This was possible in the wake of French Emperor Napoleon’s surrender on March 31, 1814, which ended the War of the Sixth Coalition. British Secretary of State for War and the Colonies Henry Bathurst had informed Prevost in early June that 12 infantry regiments that had served under Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, would sail from Bourdeaux, France, to Lower Canada. This raised the number of British and Canadian troops under Prevost’s command in Canada to 29,000.

Lt. Gen. Prevost set out from Montreal at the head of the veteran troops in late August for Plattsburg, New York, on the western shore of Lake Champlain. The lumbering column crossed the Canadian-American border on August 31. Brig. Gen. Alexander Macomb had 6,300 regulars and militia to oppose the crack British troops, who were said to have been among Wellington’s best soldiers.

Despite this looming threat, U.S. Secretary of the War John Armstrong ordered Maj. Gen. George Izard, the commander of the American Right Division, to march his 4,000 men to Sackets Harbor on the eastern shore of Lake Ontario. From that location on the east side of Lake Ontario, Izard was to sail to the Niagara Peninsula. Once his troops landed on the peninsula, he was to capture Fort Niagara and Fort George. Moreover, Izard was to assist the hard-pressed Left Division in capturing Drummond’s force.

When he received his orders, Izard recommended that his troops remain at Plattsburg, given that such a large British force was heading his way. Armstrong ignored his warning and told him to march for Sackets Harbor. Izard set out for Sackets Harbor on August 29.

Fortunately for the Americans, the British failed in their attempt in early September to capture Plattsburg. When American Captain Thomas Macdonough defeated British Captain George Downie’s squadron on Lake Champlain on September 11, an overly cautious Prevost cancelled his ground attack against the Americans holding the town. Fearing that his supply line would be cut since it was no longer protected by naval forces on Lake Champlain, Prevost withdrew to Lower Canada in disgrace.

Despite the cool reception for his proposal, Brown was determined to hit the British. For the next few days, he purposely gave the impression he was only interested in strengthening his position at Fort Erie. Brown laid out his plan on September 16 to Miller and Porter. Porter was to advance from Snake Hill with his 1,600 men on a wooded path and fall on the British right flank. The Americans had cleared the path through the woods earlier that day. The Americans would emerge from the woods 150 yards from the Battery 3.

Porter was to first destroy Battery Three and continue attacking in order to eliminate Battery Two, as well. Should he need additional support during his attack on either battery, he was to tap Miller’s force of regulars, who would be lying in wait in a ravine between Fort Erie and the British batteries. The sortie was scheduled for September 17.

Brown informed Ripley of his plan on the morning of the attack. Believing the sortie would be a disaster, Ripley initially wanted no part in it; however, he soon changed his mind. When he requested permission to command the reserve, Brown approved the request and ordered him to cover the withdrawal of the other two forces.

Porter’s detachment, which was composed of the 1st and 23rd U.S. infantry regiments and three New York militia regiments, began advancing at Noon in a light rain. The 4th U.S. Rifles and a handful of Indians screened their advance. The rain increased in intensity, and soon the troops were pelted by a heavy rainfall. The downpour afforded the attackers additional cover as they neared Battery Three.

Soldiers from the De Watteville and 8th regiments guarded the two batteries. At the time of the attack, the British were in the process of removing the guns. Porter’s men overran Battery Three. The startled me of the British fatigue party surrendered or fled. The Americans spiked the guns and destroyed the battery’s powder supply. Porter then launched his assault on Battery Two.

When he heard Porter attacking Battery Three, Brown ordered Miller to assault Battery Two, even though this was not part of the original plan. The two American forces swept over the battery with little trouble. They set about destroying the position as they had at Battery Three. The American officers decided to continue their attack by assaulting the last remaining battery, but by that time, the British had sounded the alarm. Furious at the loss of guns from two of their batteries, the British launched a determined counterattack.

Two companies of the British 82nd Regiment poured a heavy fire into the Americans at Battery Two. The sheer number of Americans crowded into the embrasure made it difficult for them to return fire, as they could not bring their muskets to bear in an effective manner. A British officer shouted for them to surrender. The Americans, who were beginning to shake themselves into fighting positions, shot the officer. Enraged redcoats rushed the battery. They lunged at some of the Americans with their bayonets. Meanwhile, amidst the chaos, the 1st and 89th regiments succeeded in retaking Battery Three.

During the confusion, Porter became separated from his men and wandered into a company of redcoats. He tried to bluff the British troops into surrendering by telling them he had troops nearby, but they did not fall for his ruse. A British soldier rushed Porter and inflicted a slight wound with his bayonet as he sought to corral him. Luckily for Porter, a detachment of American riflemen rushed to their commander’s aid. The Americans overwhelmed the British and took them prisoner.

To blunt the British counterattack, Brown sent Ripley with the reserves into the fray to help Miller and Porter withdraw, if necessary. Ripley became separated from his troops and was seriously wounded. Although his troops were unable to take Battery One, Brown was content with the damage he had inflicted to the other batteries; therefore, he issued orders to withdraw.

The Glengarry Light Infantry and British allied Indians under Captain John Norton pursued the Americans in skirmish order. By 5:00 p.m. the sortie was over. The Americans lost 511 men, while the British lost 579.

The British resumed their efforts to withdraw their guns the following day. This was no easy task, given that heavy rains made the roads impassible. Taking time to bury the dead after the sortie, it would not be until September 21 that the British Right Division withdrew from its lines. The British army retreated to Chippawa, where two days later it took up a defensive position on the north side of the Chippawa River.

After his troops destroyed the abandoned British siege lines on September 22, Brown did not immediately follow Drummond with the bulk of his troops. Brown sent a small force to probe the British position, and it skirmished the following day with the Glengarry Light Infantry, Norton’s Indians, and a detachment of provincial dragoons that screened the British main force.

Brown was eagerly awaiting the arrival of Izard’s large force, which had set sail from Sackets Harbor on September 21. Izard landed his troops at the mouth of the Genesee River and marched toward Batavia, New York, where he arrived on September 27. Brown, who was waiting for Izard at that location, conferred with him regarding the American strategy for the next phase of the campaign.

The two commanders decided that Brown would demonstrate against the British force at Chippawa, while Izard tried to retake British-held Fort Niagara. The Americans changed their plans on October 5, when they realized that they lacked the heavy artillery that would be required to ensure a successful assault on Fort Niagara. At that point, Izard resolved to join Brown at Chippawa.

Izard led his army to Fort Schlosser, New York. Because of a lack of boats at that location, he was unable to cross the Niagara River to link up with Brown. He then marched south to Black Rock, where his force was ferried over to Fort Erie. Izard joined Brown on October 15. The American force at that point totalled 7,000.

Since he had seniority over Brown, Izard took command of the combined forces. Forming his troops for battle, he attempted to lure Drummond from his entrenchments on the north bank of the Chippawa River. When Drummond refused to budge, Izard ordered Towson to bring his guns into action. An artillery duel was soon under way. Besides suffering a handful of casualties, nothing of significance was achieved by the artillery exchange.

Despite Brown’s suggestion that Izard attempt to flank Drummond on a road a mile upriver that the Americans had opened in July, Izard decided instead to continue in his efforts to draw the British out in the open. But Drummond’s men would not budge from their position. On October 17, Izard withdrew south a short distance, but he had not given up just yet.

Izard dispatched Brig. Gen. Daniel Bissell with 1,000 regulars and handful of dragoons to Cook’s Mills the following day. Cook’s Mills was situated to the west on Lyon’s Creek, a tributary of Chippawa River. Bissell had orders to destroy British supplies that the Americans believed were stockpiled at that location. Upon reaching Cook’s Mills, Bissell had his troops pitch camp. While his troops rested, engineers toiled to put in place a pontoon bridge to facilitate passage of the creek. A small force of two companies from the U.S. 5th and 16th Infantries, along with some riflemen, set up defenses to hold the bridge.

When Drummond learned that Americans troops were moving west toward Cook’s Mills, he dispatched Lt. Col. Christopher Myers to discern the Americans’ intentions. Myers commanded a detachment of Glengarry Light Infantry and seven companies of the 82nd Regiment. A short time later, Drummond sent a column of reinforcements to strengthen Myers. These troops were the flank companies of the 82nd, 100th and the 104th Regiments. The reinforcements also included a 6-pounder gun and four Congreve rockets under the command of Lt. Col. George Hay.

The combined force moved against Bissell on the morning of October 19. The Glengarry Light Infantry led the way. It struck the enemy line and steadily drove back the American light troops. The remaining British forces were quickly formed into line and fed into the fight. At the same time, the British opened fire with their 6-pounder guns and rockets.

Meanwhile, the Americans reinforced the troops holding the pontoon bridge. The U.S. 5th Infantry moved to outflank the British. Having spotted the move, Myers broke off the action after a brief fight because he lacked sufficient forces to dislodge the Americans. Myers had suffered 36 casualties, while Bissell had roughly 66 killed and wounded.

Bissell’s troops left Cook’s Mills on October 21 after destroying 200 bushels of grain. On their return to Izard’s main force, they encountered the U.S. 21st Infantry slogging through the mud to join them. They reversed course and joined Bissell in his withdrawal. It would not be long before the whole American force would be in retreat.

The American fleet on Lake Ontario had returned to its base at Sackets Harbor. This left the Royal Navy in control of the lake. To solidify their grip on it, the Royal Navy had just launched the powerful 102-gun St. Lawrence.

Taking stock of the situation, Izard believed that nothing strategic could be gained without the support of the American fleet. With winter looming and Drummond entrenched north of the Chippawa River, he decided to retreat from Upper Canada.

Brown received orders to march 2,000 American troops to Sackets Harbor in anticipation of a possible attack by a reinforced British fleet. The rest of the troops were ordered across the Niagara River to take up quarters for the winter or be discharged as in the case of the militia.

Brown’s Americans had fought with great skill throughout the summer of 1814. They went toe-to-toe with the British regulars and bested them. Unfortunately, their bravery, determination, and grit did not result in a successful campaign. The last American troops left Old Fort Erie on November 5, after blowing up the fort.