By John D. Gresham

Looking back on the age of fighting sail, a common image is that of battles between huge ships of the line, led by such famous admirals as Nelson and Collingwood. But such massive confrontations were rare, and much of Napoleonic era seapower actually was dull and mundane patrolling, cruising, and blockade duty off of enemy ports. I say “much,” because if there was an exception to the usual boredom of naval life, it was to be found aboard the greyhounds of sail-based naval presence, frigates. If ever there were glamorous ships in the dangerous world of wooden warships, they were the frigate sailing ships of the world’s navies.

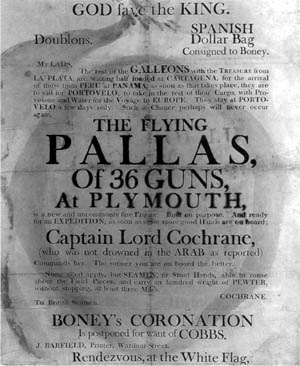

Frigates were the ships to be on, if adventure, action, and a sense of glory were your idea of navy life in the age of sail. But not all frigates in the world’s navies were so pleasant to serve aboard. Clearly that honor went to those of the Royal Navy, which reached the zenith of its power during the Napoleonic Wars, from 1793 to 1815. Frigates were the true measure of British seapower, holding the line in peace and leading the fleet in war. Aboard the frigates of the Royal Navy were found the finest officers in the service and men who frequently sought duty aboard, not the “press” (forced recruiting) gangs of the era. Frigate captains were the equivalent of modern-day rock stars to the public, respected for their daring and achievements, sought out for their acquired prize wealth and influence. These were the greatest sailors of their time, wielding the most flexible weapons system of the age. (Learn all about the naval encounters that defined the Napoleonic Era by subscribing to Military Heritage magazine.)

From Fighting Galleons to Frigate Sailing Ships

The sailing vessels that came to be called frigates had their origins in the fighting galleons of the 16th century. By the middle of the 17th century, they had begun to mature, developing the long, narrow lines that would be their trademark. Originally, these were the largest ships (called 4th Rate) not considered fit to stand in a line of battle, but still carrying at least 38 large-bore weapons on their gun decks. While they lacked the firepower, crew, or structure to slug it out in battle with the 1st (90 guns or more with three decks), 2nd (80 to 89 guns with three decks), or 3rd Rates (54 to 79 guns with two decks), they had the rigging (three masts) and speed (over 12 knots in a good wind) to run from such vessels.

On the other hand, 4th Rates could easily maneuver with and outgun the smaller 5th (with 18 to 37 guns, and often oars) and 6th (6 to 17 guns used for courier duty) Rate warships, along with the merchant vessels that were the reason for having a navy in the first place. These early frigates wound up being used for a variety of important tasks, ranging from scouting and reconnaissance ahead of the battle fleet to protecting convoys and commerce raiding on the high seas. Very quickly, navies everywhere began to see the value of frigates, both for their relatively low cost and ease of manning compared with ships of the line. Basically, frigates were fighting ships that could outrun anything that could hurt them and outgun anything that could catch them.

Over the next century, various countries evolved their own interpretations on the basic form of the frigate, each adding their own unique design ideas and touches. Some of these included the British trend of adding more sails and guns, the Dutch habit of making their vessels light with a shallow draft, and the garish French tradition of festooning their ships with ornate Baroque decorations, along with bow and stern guns. Along the way, the ratings of warships evolved as well, resulting in the classifications by the British Admiralty shown in the chart below.

As can be seen from the chart, frigates sat solidly in the middle of the warship spectrum, continuing their tradition of being able to outrun more heavily armed vessels and defeat ships of similar speed and maneuverability. They also had another advantage, one rarely mentioned in the swashbuckling stories of the time: Frigates were often kept in service in both peace and war, while the majority of larger ships were normally “laid up” as a reserve fleet, activated only at the outbreak of hostilities. While this was done as a cost-saving measure, it had very important and positive effects on the fighting qualities of the frigates.

Because frigates were normally kept in commission even during peacetime, their captains and crews tended to be among the best a particular navy could offer. These captains were usually the most aggressive in the service, chosen for their ability to think and act in both war and peace.

The Finest Navy in the World (Because it Had to Be)

Although many nations had frigate sailing ships in their fleets, those of the Royal Navy set the standard for excellence during the Napoleonic Wars. In fact, the previous century had seen England become a worldwide superpower, a status enabled by the British fleet. What set its vessels apart was as much necessitated by geographic reality as the quality of their construction and crews. Then as now, Britain was an island nation, dependent upon freedom of the sea lanes to maintain the most basic of sustenance for its people. This fact had come into being during the time of Queen Elizabeth I and Sir Francis Drake, and has been the cornerstone of British military strategy for over 500 years. In short, the Royal Navy was the finest navy in the world because it had to be. Continental powers of the Napoleonic era like France and Spain might desire maritime trade, but for Britain it was literally the breath of life.

For the Royal Navy, deploying the finest sailing frigates of the era began with a solid design, one that was easy to build and economical with regard to critical strategic materials like hardwood and metals. This was essential, because almost everything that went into English warships except the crews and guns had to be imported over the very sea lanes they would eventually protect. All the same, these frigates had to be capable of slugging it out with enemy ships of similar size and firepower and sustaining voyages lasting months without repair or resupply. This meant balancing displacement, armament, crew size, and dozens of other factors into a specification that could be translated into the wooden walls of a warship. The Admiralty Board of the Royal Navy, headed by the First Sea Lord, accomplished that job.

In the 1790s, the job went to Lord Spencer, who with input from deployed commanders and his fellow board members, laid down the basic parameters for the various rated ships that would be constructed in the coming years. By falling back on conservative, proven designs, this meant that Royal Navy frigates (5th Rates) would be based upon the 1780-vintage Perseverance class, designed by Sir Edward Hunt. Displacing approximately 870 to 900 tons and rated as “36s” (the number of guns nominally carried), these were by all accounts fine sailing ships, with all the qualities desired by the Admiralty for frigate operations. Starting in 1801, several repeat batches (a total of 15 ships) based upon the Perseverance, known as the Tribune class, were constructed. They were followed by even larger batches of improved frigates, driven by the ever-increasing demands of the threat from the Continental alliance under Napoleon. These were gradually to grow in size, eventually displacing over 1,000 tons and carrying up to 38 guns. Eventually, there were even classes of so-called “super” frigates, rated as 44s, as a direct response to the six powerful “big” frigates built by the United States of America.

“If I Were to Die This Moment, Want of Frigates Would be Found Engraved on my Heart”

The British also made extensive use of frigate sailing ships captured from enemy navies, the French units being especially popular for their fine inshore handling qualities. Nevertheless, frigates never made up more than a quarter of the 412-ship Royal Navy strength (in 1793, over 700 in 1815), causing the incomparable Lord Nelson to write, “If I were to die this moment, want of frigates would be found engraved on my heart.” There never were enough of these priceless ships to go around, something that made more than one deployed squadron commander nervous and apprehensive. Given the need to escort convoys, conduct raids along enemy coastlines, attack hostile shipping, or scout for the battle fleet, frigates were always in short supply.

One of the oddities about British frigates of this era is that while they were superb engines of war when manned and afloat, the quality of their construction was uneven. Although an excellent elm keel and oak ribs were part of every wooden Royal Navy warship, the materials and workmanship on the rest of the ship’s structure could be very marginal. Shortages of hardwood and other materials meant that lighter materials like pine were sometimes substituted. Several of the Tribune-class vessels built in Bombay were actually constructed of teakwood, though uneven quality and excessive weight offset the excellent durability of that material. As now, private contractors skimped on workmanship and materials, while Admiralty yards struggled to get the necessary output from civil service workers. Nevertheless, the frigates got built and headed for the fitting-out docks to receive their armament, supplies, and crews before sailing. It was during this “working-up” period that British frigate sailing ships began to develop the fighting qualities that made them so feared by opponents.

Although the workmanship of the construction yards might be questionable at times, the same could not be said of what the Admiralty did to make these ships ready for battle. Generally, the procurement officers of the Royal Navy did a good job of buying the tools and fuel of war, including the miles of rope (called “cordage”), acres of sail, shot, powder, guns, or the tons of hardtack bread (known derisively as “biscuits” by the crews) and salted pork and beef that made life possible afloat. While life onboard was always hard and dangerous, the British stood alone in making sure that certain minimum standards of sustenance and livability were the rights of every “Jack Tar.” Not that these were exactly up to luxury standards. Every crewman was assigned 18 inches of width to sleep in his hammock while off watch, and given a “tot” of grog (a 50/50 mix of rum and water) every day, entitlement from a grateful king and country. Water and food were strictly rationed at sea, because it might be months between visits to port for resupply. Royal Navy captains were held strictly accountable for the health and welfare of crewmen, and the memories of several particularly bad mutinies in the 1700s helped to enforce the policy.

The role of any warship is to put its weapons onto an enemy, and the sailing frigates of the Royal Navy had an impressive array for their displacement. For example, the ubiquitous Euryalus-class 36s (around 950 tons displacement) actually carried a nominal total of 42 weapons into battle. These included 26 18-pounder guns on the upper deck, 12 32-pounder carronades on the quarterdeck, and two 9-pounder cannon and a pair of 32-pounder carronades on the forecastle. Along with this main battery, every frigate had a detachment of Royal Marines, making the ship capable of conducting a variety of missions ashore. The crew could also be armed with a variety of hand weapons (pistols, cutlasses, muskets, etc.) for boarding and other off-ship operations.

A Good Commander Could Make a War Ship Legendary

If there was a real strength to the Royal Navy in general and the frigates in particular, it was the quality of their captains. Although a bad commander could make a warship almost ineffective with cruelty and excessive punishment, a good one could make the same ship legendary. Unlike most navies, Britain built its officer corps from the bottom, starting most as teenaged midshipmen apprenticed to a particular ship’s captain. From the start the midshipmen would undergo a rigorous series of lessons and examinations, leading them up through qualification to the lieutenant rank. Eventually, these officers would be considered for command of a minor 6th Rate vessel such as a sloop or armed merchantman. Only after a decade or more of honorable and effective service would an officer even be considered for frigate or higher command.

There was a strict system of seniority within the Royal Navy, which had a huge influence on promotions and appointments. Nevertheless, this seniority system was offset by the ability of senior admirals and overseas squadron commanders to make appointments for command through patronage or influence. This combination of policies had the positive effect of offsetting each other and helping create the finest pool of commanding officers (known as “Post Captains”) of the period. It was the best and brightest of these that the Royal Navy gave duty as frigate captains.

Most of the British frigate captains were young, often in their late 20s and early 30s, fully a decade younger than their contemporaries on ships of the line. There were good reasons for this beyond the simple energy and stamina of youth. Frigate captains spent most of their time away from the battle fleet or home bases, ranging across the globe to serve the interests and objectives of the Royal Navy. This independence of command was something such officers needed to embrace and celebrate if they were to meet the expectations of their king and nation. They also required aggressiveness and intelligence, with an eye for seeing opportunity and taking calculated risks.

Despite this, there was also a need for British frigate commanders to avoid recklessness and indelicacy. One day might see an English frigate captain conducting himself at a diplomatic reception with some small and obscure monarch, and the next raiding the harbors of a neighboring state. Clearly this meant that such officers required a strong sense of situational awareness and judgment in matters ranging from politics and protocol to tactics and martitime law. It was, to say the least, a unique balance of personality traits that made for a successful frigate captain. Add to this the need for leadership and management skills to man and operate his ship, along with the seamanship to sail and fight the vessel, and you get some idea of the qualities of such men.

Pellew Made a Habit of Daring Rescues

As might be imagined, British frigate skippers were towering figures who rose to the top of the naval service in peace and war. Two of the best-known captains of this era were Admirals Sir Edward Pellew and Sir George Cockburn. Born in 1757 and joining the Royal Navy in 1770, Pellew is best known in America for his depiction in the famous Horatio Hornblower novels of C.S. Forester. In real life, he was even more charismatic and colorful than in fictional accounts of his deeds. Made commander for a successful attack on a French frigate after the death of his captain, Pellew made Post Captain after doing battle with three enemy privateers in 1782. He saw action in both the American Revolutionary War and the Napoleonic Wars, where he eventually succeeded Nelson, Collingwood, and Cotton as Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet from 1811 to 1814. Along the way, he commanded the Nymph (with which he captured the French 40 La Cleopatre in 1793) and Indefatigable from which he headed the inshore frigate squadron off Brest from 1794 to 1797. Along the way he developed a habit of daring rescues, including the entire complement of the wrecked East Indian freighter Dutton. Pellew eventually rose to sit on the Admiralty Board at the end of his career, a wealthy man from his many prizes, victories, awards, and patronage.

Slightly more infamous to Americans was George Cockburn, who led the British squadron that attacked the mid-Atlantic region in 1814. Born in 1772, he joined the Royal Navy and caught the eye of Horatio Nelson, who rewarded him with early promotion and command of the captured French frigate La Minerve. Backed by an able young lieutenant named George Hardy (who would later command the flagship Victory at Trafalgar in 1805), he became Nelson’s most trusted frigate commander. Famous for his scouting missions, some of which he did from inside enemy fleet formations, he carried Nelson and his sightings to Admiral Jervis in time to precipitate the Battle of Cape St. Vincent in 1797. Made an admiral, he eventually became somewhat notorious for commanding the squadron that raided the Chesapeake Bay in 1814, personally led the Royal Marines that burned the White House, and commanded the bombardment of Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor. A year later, he was trusted with the delicate task of delivering Napoleon Bonaparte into exile on St. Helena. For his dedicated service, Cockburn was made Admiral of the Fleet and retired in 1846 after serving as First Naval Lord.

With men like this to recruit, train, and lead British frigate crews, it is easy to see how they acquired such a “bogeyman” reputation among their opponents. This elite status, even among their ship of the line peers, gave Royal Navy frigate captains the confidence and esprit to attempt all variety of missions. Almost anything, from amphibious landings and “cutting out” expeditions (capturing enemy vessels in sheltered anchorages), to swashbuckling ship- to-ship actions against superior odds became not only possible, but also expected, by the Admiralty and England.

“Super” Frigates

Impressive as the record of the Royal Navy’s frigates had been, though, the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the coming of the War of 1812 sounded the end of their dominance. The loss of a number of British 36s to American “big” frigate sailing ships like the USS Constitution caused a near panic with the British press and public, causing the Admiralty to authorize the conversion of three old 3rd Rate 74s into cut-down, two-decked, 58-gun 4th Rates called Rasées. These were followed by a handful of so-called “super” frigates with 40 (the Modified Endymion class) and 50 (the Leander and Newcastle classes) guns, respectively. However, the end of hostilities with France and America saw the end of large-scale sailing warship design and construction, along with the Age of Fighting Sail. Postwar economies after a generation of worldwide war and an odd little steam-powered vessel designed by American inventor Robert Fulton ensured that battles like Trafalgar would never occur again. Steam power, iron structures, and explosive shells would become the technologies that would drive warship design for the remainder of the 19th century and into the modern era.

Ironically, a century later, another warship pioneered by Robert Fulton, the submarine, would recapture the spirit and daring of the Royal Navy’s sailing frigates. Over two world wars and the 50-year Cold War, submarines became the most independent of naval commands, home to young, aggressive, and daring officers and men from around the world who wanted to do more than just be part of a battle line. Today, nations like the United States and Great Britain are designing their post-Cold War nuclear submarines to be much like those Royal Navy frigates of the Napoleonic era. Able to strike at sea and ashore with guided missiles, and special operations forces, these will be the new frigates for the 21st century, keeping faith with the spirit of Pellew, Cockburn, and all their sailors of that bygone era.

Military History Staff of researchers:

I believe my 5xgreat grand father , Robert Bollard , was a captain of the King’s navy , and retired sometime before 1766 in Kent, England. Additionally I believed he captained a frigate , ” Brilliant” , and cleared his ship of stores on Dec 25th 1756.

Can you direct me to any past issues of , ” Military History ” that may contain relevant information on my 5x great grandfather?

Or perhaps you can direct me to a web page that may have relevant information .

Have you tried contacting the National Maritime Museum in London? They may be able to help you with your research.

Thanks for the suggestion.

I’ll certainly give this serious investigation .