By Blaine Taylor

On March 23, 1991, at a reunion of the postwar Nuremberg International Military Tribunal staffers in Washington, I had occasion to meet the former American prosecutor, Brigadier General Telford Taylor. On May 23, 1998, the general died in New York at age 90 after suffering a series of strokes.

In his New York Times obituary, Taylor’s friend Jonathan Bush, a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, recalled, “He’ll be remembered as a chief Nuremberg prosecutor, but also more as a giant of American liberalism and a man of integrity.”

At the close of World War II, Taylor was a U.S. Army officer promoted to brigadier general as a top assistant prosecutor at the International Military Tribunal, when the four member nations, the United States, France, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union, put 21 Nazi leaders on trial at Nuremberg’s Palace of Justice. Starting on November 21, 1945, the tribunal included the missing Martin Bormann, Adolf Hitler’s personal secretary, who was tried in absentia along with the others, all for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

After 10 months of courtroom activity, 19 were convicted, two were acquitted, and a dozen of those convicted were sentenced to death by hanging. Seven other defendants received varying prison terms as sentences. Reich Marshal Hermann Göring, the ranking officer of either side in the war, committed suicide in his maximum security cell just hours before his scheduled hanging.

After the initial trial, a dozen subsequent trials took place and at these General Taylor became chief prosecutor for the U.S. team against 200 more top Nazis, and he won 150 convictions on the charges against them.

In 1947, the general stated, “The crimes of these men were not committed in rage, nor under the stress of sudden temptation. One does not build a stupendous war machine in a fit of passion, nor an Auschwitz slave factory during a passing spasm of brutality.”

The trials proceeded despite differing Allied opinions on procedures, the absence of legal precedents, and the question of whether it was right for the victors in the war to try the losers —something that, indeed, the Nazis themselves never did of their defeated foes. It was the very same argument that had also been raised after the end of World War I, when the victorious Allies demanded the extradition of the former Kaiser Wilhelm II of Imperial Germany and the top defeated German generals, among them Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and Quartermaster General Erich Ludendorff. Both the governments of the Netherlands, where the former German emperor was living in political sanctuary, and the Weimar Republic of Germany refused these extradition demands.

In 1945, the situation was different as armies from both East and West had overrun the defeated Third Reich. Thus, the accused war criminals were already in Allied hands and ready to be tried for their prewar and wartime deeds.

After all four years of trials were concluded, Taylor asserted that they had been a success, but he suggested that any future war crimes trial must look at the actions of the winners as well as those of the losers. That has yet to happen in the intervening 60 plus years; nor is it likely to.

“The laws of war are not a one way street,” Taylor asserted, a view he repeated as a law professor with his book Nuremberg and Vietnam in 1970. From this conflict emerged the trial of American Army Lieutenant William Calley and Captain Ernest Medina for crimes committed against South Vietnamese civilians at the village of My Lai in then South Vietnam.

Of his book in 1995, The Nation, a well-known weekly journal, stated, “The human rights movement owes much of its legal foundation to the work of Gen. Telford Taylor… Nuremberg gave legitimacy to the concept that the world had something to say about how governments treat their own citizens. In 1950, the United Nations codified Nuremberg’s most important statements into the seven Nuremberg Principles, which have since been adopted by the legal systems of almost every other nation.”

During the 1950s, General Taylor, back in civilian life, spoke out against U.S. Senator Joseph R. McCarthy’s (R–Wisconsin) anti-communist activities and defended some of those targeted by McCarthy. He also worked to help Jews who were imprisoned in the Soviet Union. Dealing with the Soviets had been a thorny issue during the International Military Tribunal of 1945-1946, when the defense of Hitler’s foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, accused the Soviets, as signatories to Josef Stalin’s pact with the Nazis of 1939, of having thus participated in the rape of Poland, no less than the Nazis who were in the dock of the accused.

The former general was also a professor emeritus at New York’s Columbia University School of Law and a visiting professor at both Harvard and Yale law schools and was associated with Cardozo Bet Tzedek Legal Services in New York.

Taylor’s books included the following works: Sword and Swastika: Generals and Nazis in the Third Reich (1952), The March of Conquest: The German Victories in Western Europe, 1940 (1958), The Breaking Wave: The Second World War in the Summer of 1940 (1967), and The Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials (1992). There was also Grand Inquest: The Story of Congressional Investigations.

Long after General Taylor’s role at Nuremberg is forgotten, his work as a jurist may well be eclipsed by his efforts as a scribe on the war itself.

In Sword and Swastika, General Taylor wrote, “This is the story of the combination and clash of old and new forces in Germany at a recent and critical juncture. Old and honored were the German officer class and the hard military tradition that it embodied. New and irreverent was the revolutionary surge of lethal energy that swept Germany in the early thirties, carrying Hitler and the Nazis to power. The combination of these forces was the cornerstone of the Third Reich and its resurgent might. The clash between them was the struggle for supreme power in Germany, and for control of the glittering military machine.

“The interplay of these two drives—collaboration and conflict—was the warp and woof of the Third Reich’s prewar years….

“The protagonists in this apocalyptic drama were strangely matched, the one archaic and the other atavistic. On one side, the stark, tight-lipped galaxy of professional warriors, most of whom would have been more at home in the entourage of the 19th Century German emperors: von Bock, von Rundstedt, von Kleist, von Reichenau—the names throb in our ears like the beats of a heavy war drum.

“On the other side, an incredible aggregation of demagogues, adventurers, misfits, and thugs; a veritable witches’ brew of genius and villainy: Hitler, Göring, Himmler, and Goebbels—we have no trouble recalling their features years after their deaths. Whatever their faults, they were not lacking individuality.”

General Taylor further noted, “Hitler and the officer corps each found in the other a dangerous, but necessary, vehicle for the attainment of goals which both shared; that mutual suspicions and irritations were submerged in a common design; that Hitler concealed but never neglected his purpose to bend the military to his will; that the power and traditional prestige of the generals survived Hitler’s subjection of all other groups in Germany which might have opposed him; that the officer corps thus emerged, involuntarily, as the last hope of those who sought to restore liberty and preserve peace; and finally, that the hope was betrayed, and Germany’s nightmare became Europe’s fate.”

In The March of Conquest, Taylor wrote, “At some time during the late spring of 1940, every American awoke not only to the fact of French defeat, but a chilling realization that Nazi Germany might well win the war! It was the end of an American era. In 1814, 4,000 British regulars had captured and burned the national capital, but in 1940 few Americans and fewer British knew that such a thing had ever happened. A century and a quarter had elapsed since the times when the United States was seriously endangered by foreign military power.

“National security was something that Americans took for granted, even after the brief involvement in World War I. Britain and France were friendly powers; one had the largest navy and the other ‘the finest army’ in the world. The United States ‘had never lost a war,’ and there seemed to be small chance that it would soon —perhaps ever—have to fight another.

“Then these blue horizons were darkened by the ugly cloud of Nazism … Sober statesmen predicted a long and terrible war, but American faith in French military prowess was deep-rooted, and who wanted it shaken? The Maginot Line shielded the United States as well as France.

“The Wehrmacht/Armed Forces struck, and in four weeks’ time, the French were crushed. Churchill was indomitable, but Britain was in dire straits. Suddenly the entire structure of American military security, which had endured since the turn of the century, had collapsed. The agent of its destruction was the Wehrmacht.

“A year and a half of uneasy peace remained, while the United States was riven by the isolationist-interventionist debate, but the die was already cast. America could no longer find security in the power of friendly European nations, and a large but antiquated Pacific fleet for insurance against the Japanese. To be sure, the German legions were on the other side of the Atlantic, but what would be America’s fate in a world dominated by a Nazi empire?

“France had fallen, Britain must be shored up, but for the United States, security could be regained only by the development of her own vast resources and speedy conversion of the potential to the actual. America must become and remain a great military power. So it has been ever since that spring of 1940, and so it will be as long as can be foreseen today. Few indeed must be the Americans whose lives were not deeply affected by these events ….”

In The Breaking Wave, written 15 years after the first volume of his trilogy was published, Taylor covered the Battle of Britain. “The Second World War—for most of its survivors— has remained the most intense experience of their lives, and the source of their most vivid recollections …The war was truly global, and far too extended for a single field of vision.

“There had been a time when things were simpler. After the fall of France, only three nations were at war, and of these Italy was not yet seriously committed in combat.

“The summer of 1940 was one of war between Germany and Britain, and at the time, there were many who would not have staked a thruppance on Britain’s prospects for national survival, to say nothing of ultimate victory … The English Channel became the hinge of fate for Western democracy. Alone and against desperate odds, Britain fought through under a leader who spoke winged words, and it is both just and poetic that the summer of 1940 is remembered as her finest hour.…

“For the Germans, seemingly poised on the brink of triumph, the strategic problems were both crucial and complex. Choked with territorial conquest and militarily impregnable, it was even questionable whether the Reich should continue to seek a solution vi et armis [by arms] …

“Never again was the Third Reich as close to victory as it was in the summer of 1940. That is why the German effort and its failure were, in a strategic sense, the war’s turning point, and must be accounted a crucial episode in the modern history of mankind.”

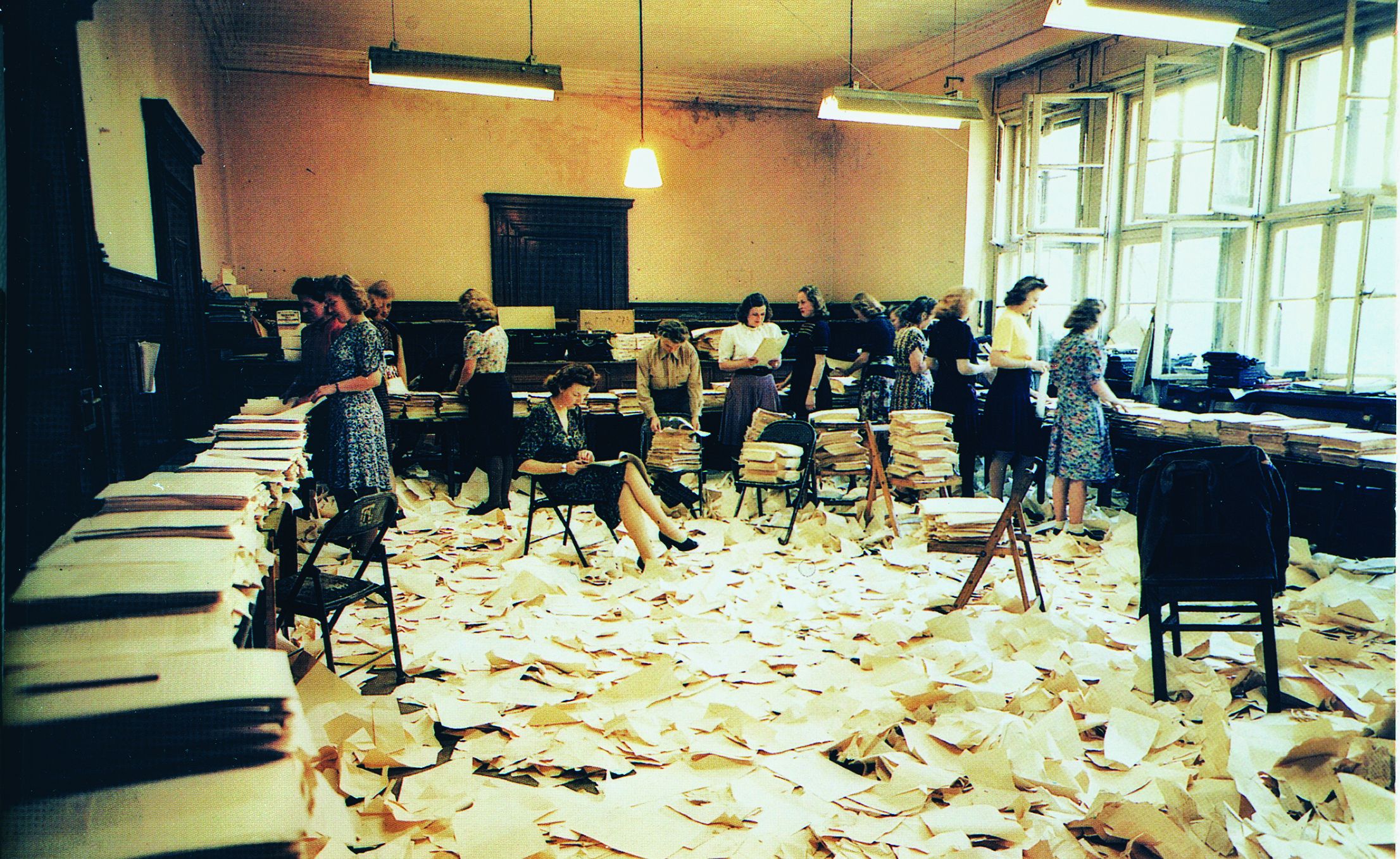

In 1992, the general-attorney came full circle with the publication of his final book, The Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials. He wrote, “In the spring of 1945, I was a reserve colonel in the intelligence branch of the United States Army. My duties had to do with information derived from the deciphering of enemy messages, the product of which in recent years has become known as ‘Ultra’ and ‘Magic’…

“Robert H. Jackson, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, had been appointed by President Truman to represent the United States as chief prosecutor at a projected international trial of ‘war criminals.’… I had graduated from Harvard Law School in 1932, and during the next 10 years, had held a succession of Federal government legal positions. In 1939-40, I had served briefly as a Special Assistant to the Attorney General (Jackson).”

Prior to Harvard Law School, Taylor had graduated from Williams College, and during the war he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. In 1979, his book Munich: The Price of Peace was awarded the National Book Critics Award for best nonfiction work.

His career as a writer closed as it began, on Nuremberg, however; and, surprisingly, he recanted his previous view that Nazi Jew-baiter Julius Streicher, Gauleiter (regional leader) of Nuremberg and Franconia and editor of the anti-Semitic newspaper Der Sturmer (The Stormer) should have been both convicted and hanged.

In the “politically correct” climate of the 1990s, the general concluded that Streicher and Nazi philosopher Alfred Rosenberg had both been unjustifiably convicted and hanged, largely because of the unpopularity of their political views, speeches, and writings.

It was a remarkable about-face for a truly remarkable author and preeminent jurist to make but wholly in character with General Telford Taylor.

Towson, Maryland, author Blaine Taylor is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He has written numerous books on World War II topics

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments