By Sam McGowan

Most military historians consider the Battle of Midway to be the turning point of World War II in the Pacific. Considering only the naval role, this is probably true. However, in spite of the loss of most of their main aircraft carrier force at Midway in June 1942, the Japanese military was still very much a powerful force throughout the Pacific, especially in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands in early 1943. (Get full, in-depth coverage of the battles and conflicts that shaped the history of the South Pacific inside WWII History magazine.)

There, the Japanese had established a series of bases as stepping-stones in their strategy of defeating the Allies by extending the Greater East Asia Prosperity Sphere to the very doorsteps of the continent of Australia. All of the Japanese plans fell apart, however, at 10 am on March 3, 1943, in the Bismarck Sea just off the New Guinea coast from Lae. In the span of about 15 minutes the Japanese lost World War II. And there was not a single U.S. Navy ship or carrier-based airplane involved.

Immediately after the Japanese attack on U.S. military facilities in Hawaii, hundreds of thousands of young men heeded the call from the White House and War Department to “Remember Pearl Harbor” and rushed to the nearest recruiting center to enlist. With only a few exceptions, they were then put into the training pipeline to staff units that were being organized to go to Europe to assist the British in defeating Germany. While the Navy and its Marine Corps would fight in the Pacific, the Pearl Harbor attacks had so devastated the U.S. Pacific Fleet that there was very little they could do in 1942.

On December 21, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt made the decision to write off the Philippines and throw the bulk of America’s might into the war in Europe, while sending a token force into the Netherlands East Indies to defend the oil fields. The Allied Java Campaign was a failure, and Australia was threatened as Japan moved its troops farther and farther south.

Australia is Left Threatened by Japanese Expansion

Before drawing off thousands of her young men for duty in North Africa, the British promised the Australian government that they would defend the country if the Japanese attacked. When war came, the British forces in Asia were as severely mauled as the Americans were in the opening days of the war. The Australians turned to the United States for help, but all they got were a few Army Air Corps stragglers who had been on their way to the Philippines when the war broke out and had been diverted to Australia when the Japanese Navy blocked the sea lanes.

These refugees were joined by others who came out of the islands as the Japanese began pushing the American and Filipino defenders onto the Bataan Peninsula. Although Roosevelt promised General Douglas MacArthur that reinforcements were on the way, no ground units and only a handful of air units were sent to Australia in the opening months of the war in the Pacific. It would be nearly nine months after Pearl Harbor before U.S. ground combat troops would enter combat in the Southwest Pacific.

Australia was very much threatened by the time U.S. Army Air Corps Maj. Gen. George Churchill Kenney arrived in the summer of 1942 to take command of all Allied air units in the Southwest Pacific. Just after his arrival, a Japanese amphibious force landed at Buna on the north side of the Lae Peninsula and begun advancing southward over the Kokoda Track, a footpath that ran over the top of the rugged Owen Stanley Mountains. In spite of the hardships and rugged terrain along the track, the Japanese advanced southward toward Port Moresby, the last Allied military outpost between them and Australia.

The Battle of the Coral Sea was a military draw, but it kept the Japanese from making a landing on the south side of Papua, New Guinea, and taking Port Moresby before the Allies could build up an effective defense. The Japanese tried again, landing a small force at Milne Bay, but they were met by Australian troops who defeated the Japanese landing party and drove them back into the sea.

Kenney realized that air power was going to be the single most effective weapon in the Southwest Pacific Area of Operations, and he immediately began organizing his forces to make them the offensive weapon that was so badly needed in the theater. In spite of opposition from the ground officers on General Douglas MacArthur’s staff, Kenney began making use of the fighters, bombers, and troop carrier transports under his command to start pushing the Japanese to the other side of the mountains and, ultimately, out of New Guinea altogether. In the late winter of 1942-1943 the Allies won a major victory when they defeated the Japanese forces at Buna.

In spite of that victory, there was a problem. The Japanese were still able to reinforce and resupply their air and ground forces at Lae with convoys sailing from Rabaul Harbor on New Britain. Kenney’s Fifth Air Force had become skilled at intercepting the convoys and occasionally sinking a ship or two, but the majority of the transports got through and the garrison and air forces at Lae remained strong.

In early February 1943, the Allies learned through radio intercepts that a large convoy was forming to transport more than 9,000 fresh troops to Lae, and once they got there the Japanese intended to use them to regain the offensive on the Lae Peninsula. With very few naval forces in the theater and no carrier planes, the only instrument capable of finding and defeating the supply effort was Kenney’s own Fifth Air Force and its record along those lines was not very good.

Kenney and Benn Introduce Skip-Bombing

While on the way to his new assignment in Australia, Kenney and his aide, Major Bill Benn, had discussed the merits of skip-bombing as a means of attacking ships. The idea was for an airplane to drop a bomb from very low altitude so that the forward motion would cause the bomb to skip along the surface like a rock. The concept had originated before the war while Kenney was assigned to the Army Air Corps research and development branch. British aircraft had used the tactic with some success in the Atlantic.

During a rest stop in the South Pacific, Kenney and Benn borrowed a Martin B-26 Marauder bomber and made some test runs with a coral reef as a target. When they arrived in Brisbane, Kenney relieved Benn as his aide and gave him command of the 63rd Bomb Squadron, a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress squadron assigned to the 43rd Bombardment Group. Before he left for his new unit, Kenney ordered Benn to teach skip-bombing to the pilots in his squadron and to use the tactics against Japanese ships.

The skip-bombing B-17s proved to be effective, but there was a problem with their employment. Since the Boeings were lightly armed in the nose, they were vulnerable to fire from the target ships during their approach. Due to their vulnerability on skip-bombing missions, Kenney restricted the B-17s to night attacks and looked for another weapon to use against shipping.

Modified B-25s Prove to Be Powerful Weapons

When he first arrived in Australia, Kenney met Captain Paul I. Gunn, a former U.S. Navy enlisted aviator and mechanics mate who was making extensive modification to the Douglas A-20 Havoc bombers of the 3rd Attack Group. Gunn had developed a package of four .50-caliber machine guns that he installed in the nose of the A-20, along with two more guns in pods on the side. Gunn suggested that the North American B-25 Mitchell bomber could be similarly modified, but Kenney told him to wait until the A-20s proved the concept. When the A-20s went into combat, the results were so spectacular that Kenney immediately authorized Gunn to similarly modify a squadron of B-25s.

By December Gunn had worked up a package of six .50-caliber guns in the nose of a B-25, with two more in pods on the side, for a total of eight forward-firing guns. Kenney believed the modified B-25s were the answer to his search for a “commerce destroyer,” an airplane that could attack ships at low altitudes in a combination strafing/skip-bombing attack.

By early February the Fifth Air Force service command had modified a dozen B-25s, enough to equip a full squadron. General Kenney had selected the 90th Bomb Squadron of the 3rd Attack Group to fly the airplanes, and the squadron commander, Major Ed Larner, was ordered to learn the skip-bombing method and check out his crews. The A-20 crews of the 89th Bomb Squadron were also instructed on how to skip-bomb, although none of the crews flew any practice missions. The B-25 skip-bombers trained by skipping bombs into the side of the wreckage of a British ship that had run aground in the harbor at Port Moresby several years before the war.

Some of the Allied leadership believed that the reason previous air attacks had failed to halt the New Guinea-bound convoys was because they had been carried out piecemeal. They theorized that a concentrated attack by a large force would be sufficient to severely hamper a convoy’s progress. On February 28, while the Japanese convoy was assembling in the harbor at Rabaul, Fifth Air Force crews, including Royal Australian Air Force Beaufighter and Beaufort pilots and observers, carried out a coordinated practice mission on the wreck.

The plan called for B-17s from the 43rd Bomb Group and B-25s from the 38th Bomb Group to attack the convoy from medium-level altitudes immediately before a masthead-level attack by the skip-bombing strafers from the 3rd Attack Group. The RAAF Beaufighters would go in just ahead of the skip-bombers to attack the gun crews with machine-gun and cannon fire. The attack force would be protected by P-38s from the 35th and 49th Fighter Groups. The 90th Bomb Group’s B-24s would carry out reconnaissance missions tracking the convoy’s progress.

The Ill-Fated Japanese Convoy Begins

Early on March 1, 1943, the Japanese convoy set sail from Rabaul and onto the pages of military history. Although the number of ships and men involved is open to dispute, Japanese naval records indicate that the convoy was made up of seven transports and a naval special service ship carrying more than 6,000 ground troops and aviation personnel to reinforce the garrison at Lae. Although Allied reports indicated that there were cruisers as part of the convoy, the Japanese reported that there were an equal number of destroyer escorts for the eight ships, bringing the total to 16. Allied reports indicated that as many as 22 ships were part of the convoy by the time it reached the Bismarck Sea.

The first Allied contact with the convoy was on the afternoon of March 1 when a 90th Bomb Group B-24 Liberator diverted from its original course down the north coast of New Britain due to bad weather and came down the south coast instead. The Liberator’s navigator spotted the convoy. The crew reported there were 14 ships—six destroyers and eight transports. Japanese radio stations picked up the message from the B-24 and reported that they had been sighted. Equatorial weather prevailed over the Solomon Islands at the time, and the convoy quickly disappeared beneath the clouds. Fifth Air Force headquarters dispatched more long-range B-24s to find the convoy, and that evening the first attack was made. A B-24 crew dropped four bombs from 1,500 feet but reported no hits. An hour later a flight of B-17s dropped flares over the believed position of the convoy but made no actual sighting as the convoy steamed below them beneath the clouds.

Another B-24 crew sighted the convoy again the next morning and remained overhead until a flight of B-17s arrived. At 9:50 am, seven B-17s made an attack from 6,500 feet in spite of rain and the presence of Japanese fighters. Although the record of level-bombing attacks against ships by Army bombers was poor, the formation managed to hit one of the transports and set it on fire. The transport Kokusei Maru sank later in the morning, but the destroyers picked up several hundred survivors.

Several attacks by B-17s and B-24s resulted in only moderate damage to one of the other transports, although the bomber crews reported two ships on fire and another sinking. After the attacks, two destroyers left the convoy and went ahead at high speed to deliver the survivors to Lae. After disembarking the troops, the destroyers returned to the convoy.

Apparently under the impression that bad weather made the convoy safe from further air attacks, the Japanese commander, Admiral Shofuku Kimura, decided to circle the ships during the night in order to arrive off Lae the following morning instead of coming in under the cover of darkness. Had he continued on into Lae, the ships would have been in the harbor by morning and disembarking their passengers and cargo. Instead, they were just south of Finschhafen and still several miles out to sea at mid-morning.

An Australian Catalina seaplane was sent out to monitor the convoy during the night. Just before dawn the PBY crew made a pass over the convoy and dropped four 250-pound bombs but did no damage. During the early morning hours, a flight of RAAF Beaufort torpedo bombers attacked the convoy under the light of flares. Unfortunately, they were carrying U.S. torpedoes, which were plagued with problems. None of the torpedoes struck the ships, but the Beaufort crews made several strafing passes, giving the ships’ crews a foretaste of what was to come.

Allied plans called for the formations to assemble over Cape Ward Hunt at 9:30 am and to attack the convoy at 10:00. When Major Ed Larner got the word that the attack was on at 8:55, he shouted to the crews in his squadron, “Cape Ward Hunt, 0930—let’s go!” The 90th Bomb Squadron commander jumped into his B-25 and began starting engines. The A-20 crews of the 89th Bomb Squadron did likewise. They had been briefed that their job would be to “mop up” behind the B-25s, which would be the primary attacking force. A formation of

B-17s would attack the convoy ahead of the strafers, forcing them to break out of their formation and scatter, making them easier targets for the low-level attacks. The skip-bombing A-20 crews were expecting to take as many as 50 percent casualties in the masthead attacks.

As the attack formations approached the convoy, the Japanese sailors and the troops they carried were preparing to approach Lae and the safety of the harbor. They believed they were safe from Allied air attack and that if it came the fighter squadrons based in the vicinity of Lae would break it up before the bombers could do any damage. There were Japanese fighters in the vicinity and they headed for the B-17 formation that was approaching the convoy, only to be intercepted by the P-38s of the 39th Fighter Squadron, led by Major George Prentice.

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea: a Melee Ensues

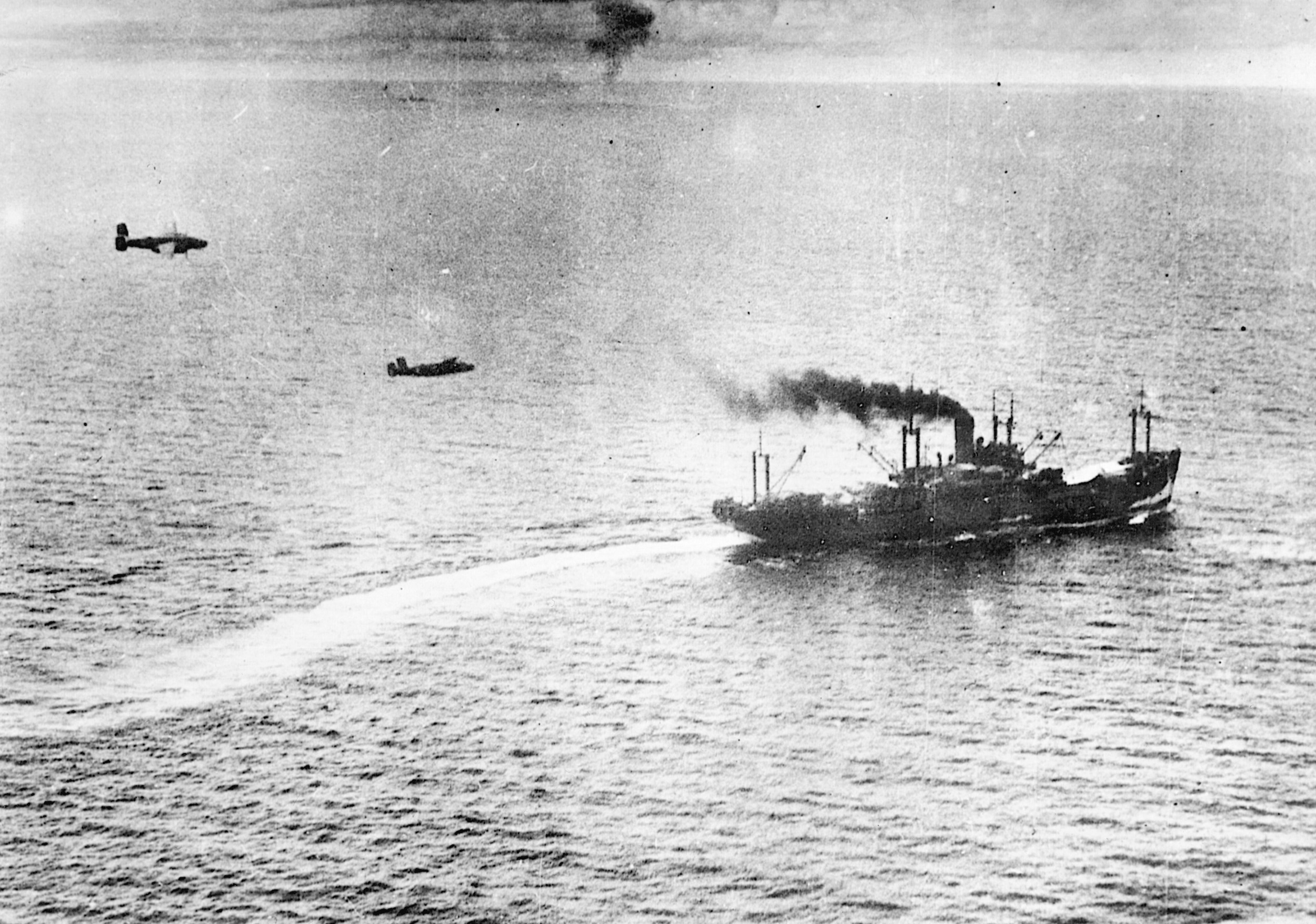

What happened next can only be described as a melee. Although the attacks were supposed to be coordinated, it appears that all of the attack aircraft more or less struck the convoy at once. While the B-17s and medium-level B-25s were attacking from higher altitudes, the RAAF Beaufighters came in on the deck and began strafing the ships. They were joined by the 90th Squadron B-25s, whose attack signaled the death knell for the convoy.

Although the 90th Squadron was an American outfit, many of the crewmen were Australian airmen who had been integrated into the squadron to make up for shortages in personnel. They flew as co-pilots, gunners, and radio operators. As the B-25s leveled off over the waves after diving down from higher altitude to begin their attack, they saw the splashes of drop tanks from the P-38s that were going in to break up the fighter attack on the higher flying B-17s and B-25s.

Larner headed for a large transport and his three wingmen stayed with him. He told them to “find your own targets” and they each broke away. Larner attacked a large destroyer with two bombs, scoring a hit with one and a near miss with the other. He then headed for a transport, got one hit on it, and followed up with an attack on a destroyer.

Lieutenant Charles W. Howe was one of Larner’s wingmen. He went after a transport and dropped two bombs, but no one saw their results. Howe then attacked another transport and got one direct hit amidships and a near miss that left the ship dead in the water and obviously sinking. The young pilot strafed another transport then left the battle at low altitude.

Captain John “Jocko” Henebry was leading the second element of B-25s. After being forced away from one target when Chuck Howe flew in front of him, Henebry focused his attention on another transport, going in with guns blazing and spraying the decks with .50-caliber fire. One of his bombs smacked into the side of the transport and another missed. Henebry strafed two other ships then departed the vicinity of the convoy. Lieutenant John Smallwood put two bombs into a transport and dropped two others on the bow of a second. Mixed in among the attacking B-25s were the cannon-firing Beaufighters.

Right on the heels of the 12 B-25s from the 90th Bomb Squadron came a dozen A-20s from the 89th. Led by Captain Glen Clark, the first wave of six A-20s tore into the doomed ships. The crews saw explosions aboard some of the stricken ships and fire from others as Clark led his squadron along the southern flank of the convoy before turning in for the attack. Captain Ed Chudoba released two bombs on a freighter and clipped the ship’s radio mast with a wing as he pulled up and over the transport. Aerial photographs recorded the explosions and the name of the transport, Taimei Maru.

Captain Glen Clark bombed the same ship, which was set on fire. Captured dairies kept by Japanese sailors and soldiers recorded that the decks were washed with a sea of blood. Captain Dixie Dunbar and Lieutenant Jack Taylor went after Kembu Maru, the smallest ship in the convoy. Their attack left the ship sinking, the first in the convoy to go to the bottom on that bloody day. By the time the A-20 and B-25 skip-bombers finished with the convoy, every single one of the transports had been hit a number of times and several of the destroyers were badly damaged.

Fortunately for the skip-bombers, the Japanese fighters from Lae had concentrated their attacks on the higher flying B-17s and medium-level B-25s. One B-17 was shot down, and when the crew bailed out they were attacked by Japanese fighters while they hung in their parachutes. Apparently Captain Bob Ferrault, a P-38 pilot and flight leader in the 39th Fighter Squadron, saw a B-17 under attack and led two other P-38s down to help. All three fighters were shot down, the only P-38s lost that day. Ferrault was believed to have been seen in a yellow life raft floating near the remnants of the convoy later in the day. The P-38s claimed 27 Japanese airplanes shot down, 12 probables, and nine damaged during the battle for a loss of three of their own.

As the skip-bombing A-20s and B-25s began departing the area, or possibly while they were still attacking, a formation of B-17s dumped its bombs on the doomed convoy. They were followed by more B-25s flying at medium altitudes. Another low-level attack was made by B-25s that had yet to be modified into strafers. All claimed hits on the transports and their destroyer escorts. By 10:15, 15 minutes after the initial attack, all seven transports had been hit and some were sinking. Three of their destroyer escorts had also been badly damaged or had already sunk. Within the span of a quarter of an hour, Japanese hopes for regaining the offensive in Papua, New Guinea, were sinking into the depths of the Bismarck Sea.

The Second Round of Attacks Begins

Even though the battle had been won, the Fifth Air Force was not through with the Japanese convoy. The convoy had been within a few miles of shore when it was struck, close enough that survivors could possibly make it to safety on shore to later be thrown into the front lines to reinforce the Japanese troops at Lae. General Kenney and the American and Australian combat commanders beneath him had no intention of allowing that to happen. As soon as they returned to their departure points, the attack aircraft were rearmed, refueled, and turned around for a second attack in the afternoon.

The ferocity of the attacks was not lost on the Japanese, although they attempted to reinforce the embattled convoy. At 12:10 pm a Fifth Air Force Liberator spotted four warships steaming away from the convoy. They were the four still-serviceable escort destroyers, which were steaming toward Rabaul to meet other ships that were coming out to pick up survivors and refuel the warships. By mid-afternoon four transports were still afloat, but barely, while only two destroyers (or, according to some accounts only one) remained with them. Hundreds of Japanese sailors and soldiers were in the water, some in lifeboats and others clinging to flotsam.

Almost five hours after the initial attack, a flight of Royal Australian Air Force A-20s attacked the convoy in spite of being intercepted by some 25 Japanese fighters that had come out from Lae to provide an umbrella for the stricken ships. Two of the A-20 crews scored hits on a damaged destroyer. The crews reported that there were four ships and two destroyers still afloat, but that all six were dead in the water. Flying Fortress crews from the 63rd Bomb Squadron reported that there were five transports and two destroyers afloat at 12:05, with a third destroyer steaming north away from the convoy. The destroyer Asashio was subjected to a massive attack by bombs and low-altitude strafing by B-17 crews who came down to 200 feet. The B-17 attack was followed by another low-altitude assault by the B-25 strafers.

The skip-bombing/strafing attacks by the 90th Bomb Squadron’s modified B-25s were as violent as had been the ones in the morning. This time, however, the skip-bombers met fighter opposition, although the Japanese attacks had little effect. The gunners on the B-25s fought off the fighters while the pilots went after the ships.

Lieutenant Charles W. Howe attacked five ships during his time with the convoy, scoring two bomb hits on an already damaged transport. Captain Jock Henebry made 15 strafing and bombing passes in spite of fighter opposition. His gunner shot down one of the fighters and the rest backed off. After strafing the ships, the B-25 pilots turned their guns on the survivors and pieces of wreckage in the water. Their orders were to completely destroy everything, to not allow a single box of supplies or a single soldier to reach shore.

Just as in the morning, the strafing attacks were coordinated with medium-level attacks by B-17s, B-25s, and a handful of B-24s. Although most of the bombs dropped from the higher altitudes fell in the water, some struck the already damaged ships. By this time it really did not matter where a bomb fell as there were so many Japanese in the water that it was bound to hit something.

By the time the last bomber left the vicinity, the convoy had been totally destroyed. Only one transport was still afloat, along with two destroyers that had managed to escape the dreadful onslaught. The sea for 20 miles around was filled with everything imaginable from the ships—pieces of lifeboats, crates of drenched supplies, dead and dying men, all floating among the survivors from the vessels that were now at the bottom of the Bismarck Sea.

A Nightmare for the Japanese Survivors

For the Japanese survivors, the battle had been a nightmare, one that was never going to end. As the first attackers were approaching the convoy, the Japanese troops were preparing to disembark from the transports. Many were on deck where they were being addressed by their officers, who were telling them that their voyage was now over, that their air force would protect them. Even when the first American bombers appeared overhead, most of the sailors and soldiers expected that the bombs would fall harmlessly in the sea like most bombs did.

When the low-flying skip-bombers approached the convoy, those who saw them believed they were going to carry out a torpedo attack, which was little cause for alarm since American torpedoes had a reputation for failing to explode. But when the .50-caliber guns started raking the decks and the bombs began smashing into the sides of the ships, the hearts of the Japanese were filled with horror. Dozens of men fell beneath the hail of machine-gun fire, while others fell before the shrapnel that filled the air as the bombs struck home, causing explosions inside the bowels of the transports. Blood washed across the decks of the ships and spilled into the green waters of the Bismarck Sea, turning it red. And things were only going to get worse.

That evening when darkness fell, the U.S. Navy PT boat flotilla sortied from its base at Tuli, on the New Guinea coast. The blackness of the night made it difficult for the fast boats to maneuver among the flotsam strewn over the surface of the ocean. Two of the boats struck pieces of wreckage and had to return to port. Eight others continued into the area where the last ships had been sighted. They found the derelict transport Oigawa Maru and sank it, but failed to locate the two surviving destroyers that were still in the vicinity. With the sinking, every single one of the eight transports that had set sail from Rabaul was now on the bottom.

After the battle, the sea was filled with survivors. Some were in boats, some clung to debris, and others just floated in their lifejackets, if they were fortunate enough to have one. Many of the survivors were within swimming distance of the shore and therefore still a threat to the Allied personnel on the Lae Peninsula. Fifth Air Force headquarters determined that it was in the Allies’ best interest to kill every Japanese they could, so on the morning of March 4 the bombers and fighters returned to the scene of battle.

A B-24 arrived first, and the crew spotted several motorized launches that were on their way to pick up survivors. Over the next several hours Fifth Air Force aircraft strafed anything and everything that moved on the surface of the sea. Huge four-engine B-17s dropped down to masthead heights so the gunners could strafe the Japanese survivors. Japanese fighters attempted to shoot down the attackers, but with little success.

Modified B-25 strafers from the 90th Bomb Group went after anything that resembled a Japanese vessel, and when none could be found, they turned their guns on the Japanese survivors in the water. RAAF Beaufighters and USAAF A-20s escorted by P-38s attacked the airfields around Lae and Finschhafen to keep Japanese aircraft on the ground. The strafing of lifeboats and survivors in the water continued for several days aided by U.S. Navy PT boats.

A Turning Point in the Pacific War

In spite of the carnage, a little less than half of the Japanese participants survived the battle and its immediate aftermath. U.S. Naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison estimates that 2,734 Japanese survivors were picked up by Japanese destroyers and submarines.

The majority of the survivors were returned to Rabaul, although some made it into Lae and some managed to swim ashore. The occupants of one lifeboat sailed 700 miles to land on Guadalcanal, only to be discovered and killed by an American patrol. Other survivors reached land on Goodenough Island, but were captured or killed by Australian troops after their presence was reported by the natives.

Although the Battle of the Bismarck Sea involved no American or Japanese warships, other than the Japanese destroyers escorting the convoy and the U.S. Navy PT boats that came in at the end, it was a major World War II naval battle and a turning point in the war in the Pacific. The success of the American and Australian aircrews proved once and for all the theories put forth by Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell that land-based bombers were a highly effective weapon against ships.

Prior to the destruction of the convoy, the Japanese had managed to reinforce and resupply their troops in New Guinea in spite of frequent air attacks, but the debut of the skip-bombing A-20s and B-25s made Japanese resupply efforts extremely costly. Never again would the Japanese attempt to send a convoy to Lae. All future resupply efforts would be by barges that hugged the shoreline of New Britain until they were close enough to make a dash across the Vitiaz Strait to Finschhafen, often under the cover of darkness, then once again hug the coast until they reached the safety of the harbor at Lae. As often as not, the barges fell victim to strafing A-20s and B-25s.

Kenney Lobbies for the More Air Power

Fifth Air Force commander Kenney left the Southwest Pacific with General Richard Sutherland and their aides for a conference in Washington, DC, on March 4, the day after the devastating attack that sank Japanese hopes for regaining the offensive in New Guinea. He took with him the heady news that his men had delivered a major blow to the Japanese in the theater commanded by his boss, General Douglas MacArthur.

During a stop in Hawaii, Kenney briefed a skeptical Admiral Chester Nimitz and other military dignitaries on what he knew about the battle. From there, he continued on to Washington, DC, for the commanders conference in which Kenney made his pleas for additional aircraft and the crews to fly and maintain them for his theater. He also met with President Franklin Roosevelt and briefed him on the battle. The obvious victory in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea was undoubtedly a determining factor in the president’s decision to influence the Joint Chiefs and encourage them to divert some assets to the Fifth Air Force.

One of Kenney’s requests was that the North American Company begin converting production B-25s into strafers on the assembly lines so that his already overworked Air Service Command depots would not have to do it in the field. A team of Army Air Forces engineers came to Washington to tell the Fifth Air Force commander that the plans he had sent them in advance of his visit were not workable. They said that the changes made by Major “Pappy” Gunn and his maintenance team in the field would make the airplanes too heavy and that the center of gravity would be too far forward.

Kenney told them in front of Hap Arnold that 12 so-modified airplanes had played a major role in the recent victory in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea and that his depots were in the process of converting 50 more B-25s in the field. Arnold told Kenney he wanted Gunn to come back to the States to “teach the engineers” a thing or two. The Army Air Forces commander wanted the transfer to be permanent, but Kenney convinced him to make it temporary. Gunn came to the States on Arnold’s order and visited both the Army Air Forces engineering facilities at Wright Field, Ohio, and the North American Company’s aircraft factory, suggesting numerous modifications to the B-25 that were incorporated in models starting with the cannon-equipped B-25G.

With the tactics used in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, Kenney realized that his men could now control the seas in the Huon Gulf and prevent the Japanese from reinforcing their forwardmost installations. Without supplies, the Japanese airfields at Lae were rendered ineffective within a month of the decisive battle. In September, Lae itself fell into Allied hands. Although the original Allied plan had called for the capture of Rabaul, Kenney convinced MacArthur that the Fifth Air Force could isolate the place so that the Japanese installation would “die on the vine.”

An aerial campaign against Rabaul was begun immediately after the fall of Lae as Fifth Air Force B-25s went into the harbor and attacked Japanese ships in their moorings. In February 1944, Rabaul was ruled as “neutralized” by the combined efforts of Army, Navy, and Marine air power.

Sam McGowan is an expert on aviation in World War II. He is the author of The Cave, a novel of the Vietnam War, and resides in Missouri City, Texas.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments