By Michael D. Hull

Operation Bolero, the marshaling of Allied forces for the planned 1944 invasion of Normandy, was in full swing by late 1943, and much of England had been turned into a great armed camp.

While the British, Canadian, and Free French Armies trained in the east, south, and north, American armored, infantry, and airborne divisions were concentrated in the Midlands, the Southwest, and southern Wales. Across the meadows and farmlands of Dorset, Wiltshire, and Devon, thousands of young GIs made their new homes in Nissen huts and tents, griped about warm beer and the weather, and made friends with local folk in teashops and inns during off-duty hours.

They learned battlefield tactics in wide-scale maneuvers and sweated through grueling route marches while long columns of tanks, jeeps, trucks, and half-tracks rumbled through ancient villages and clogged the narrow, winding lanes. Stores of equipment, vehicles, and fuel were hidden in woodlands and spread across fields. Massive preparations were under way for the long-awaited liberation of Western Europe.

The American soldiers’ training was made as realistic as possible, with an emphasis on amphibious tactics because they and their Allied comrades would be landing in northern France from the English Channel, stubbornly opposed by seasoned German defenders. While many of the other Allied troops had little or no combat experience, the vast majority of the Americans had seen no action at all. Out of 15,000 men in the U.S. 29th Infantry “Blue and the Gray” Division, newly arrived and destined to land on Omaha Beach, only five had been under fire.

Exercise Tiger

Late in 1943, the British War Cabinet approved the building of two 25-square-mile assault training centers for the U.S. troops in Devon—one on the scenic northern coast between Appledore and Woolacombe and the other between the ports of Brixham and Salcombe on the southern coast. The central stretch of the latter coastline, Slapton Sands in Start Bay, was earmarked for the U.S. 4th Infantry “Ivy” Division because it was strikingly similar to Utah Beach, the division’s assigned invasion beach in Operation Overlord.

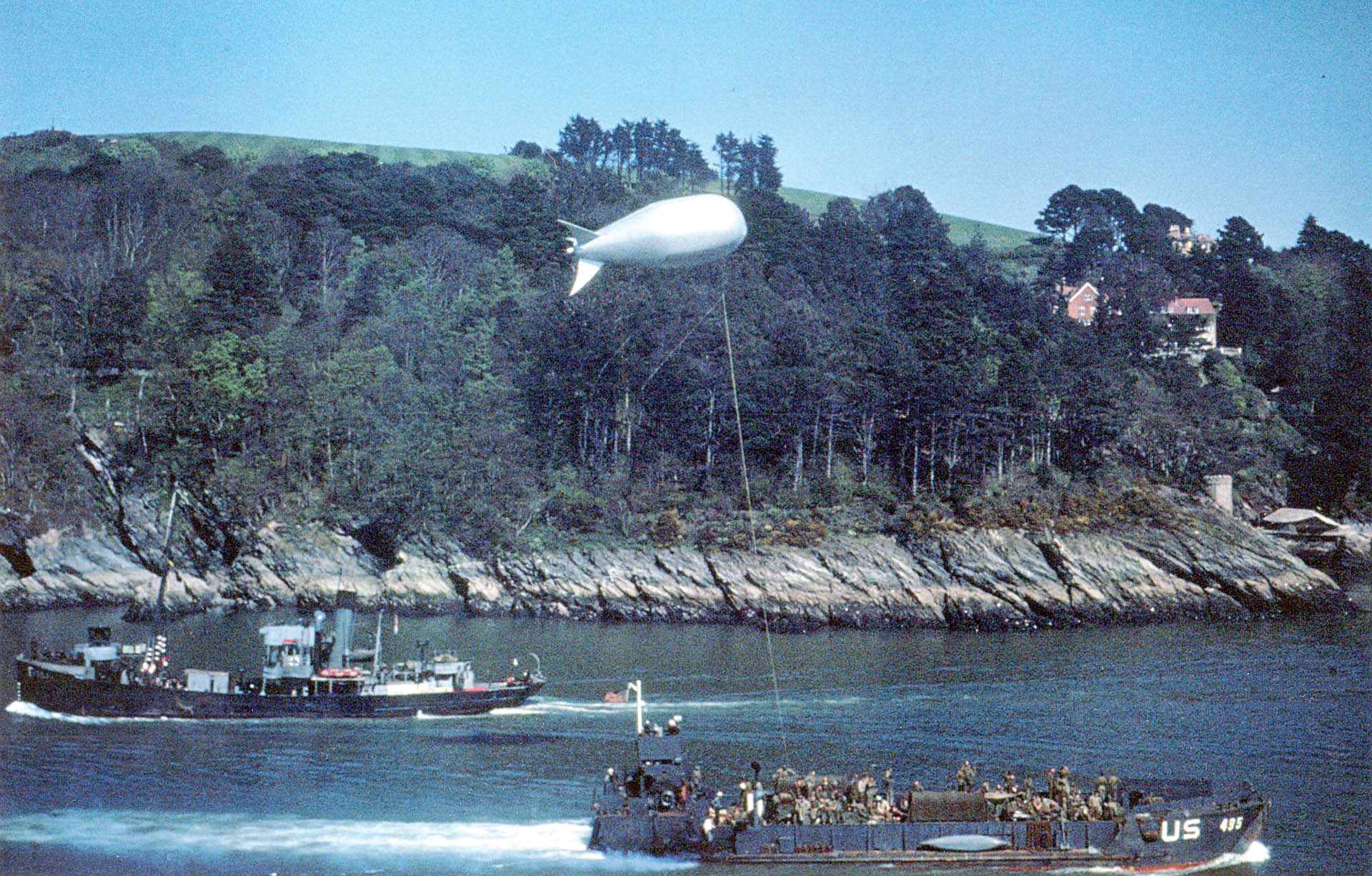

From the summer of 1943 onward, southwestern England became an American training area. The U.S. Navy took over several bases in the Royal Navy’s Plymouth Command, and the Stars and Stripes was hoisted over six new landing craft maintenance and repair centers along the southwestern coast.

At public meetings early in November 1943, officials of the six principal villages in the Slapton Sands area were informed that about 2,750 residents were to be displaced and 17,000 acres of farmland placed under U.S. Army control by December 20. That month, Royal Navy officers set up offices in the area and supervised the evacuation of families who for generations had fished in the Channel waters or farmed the surrounding countryside.

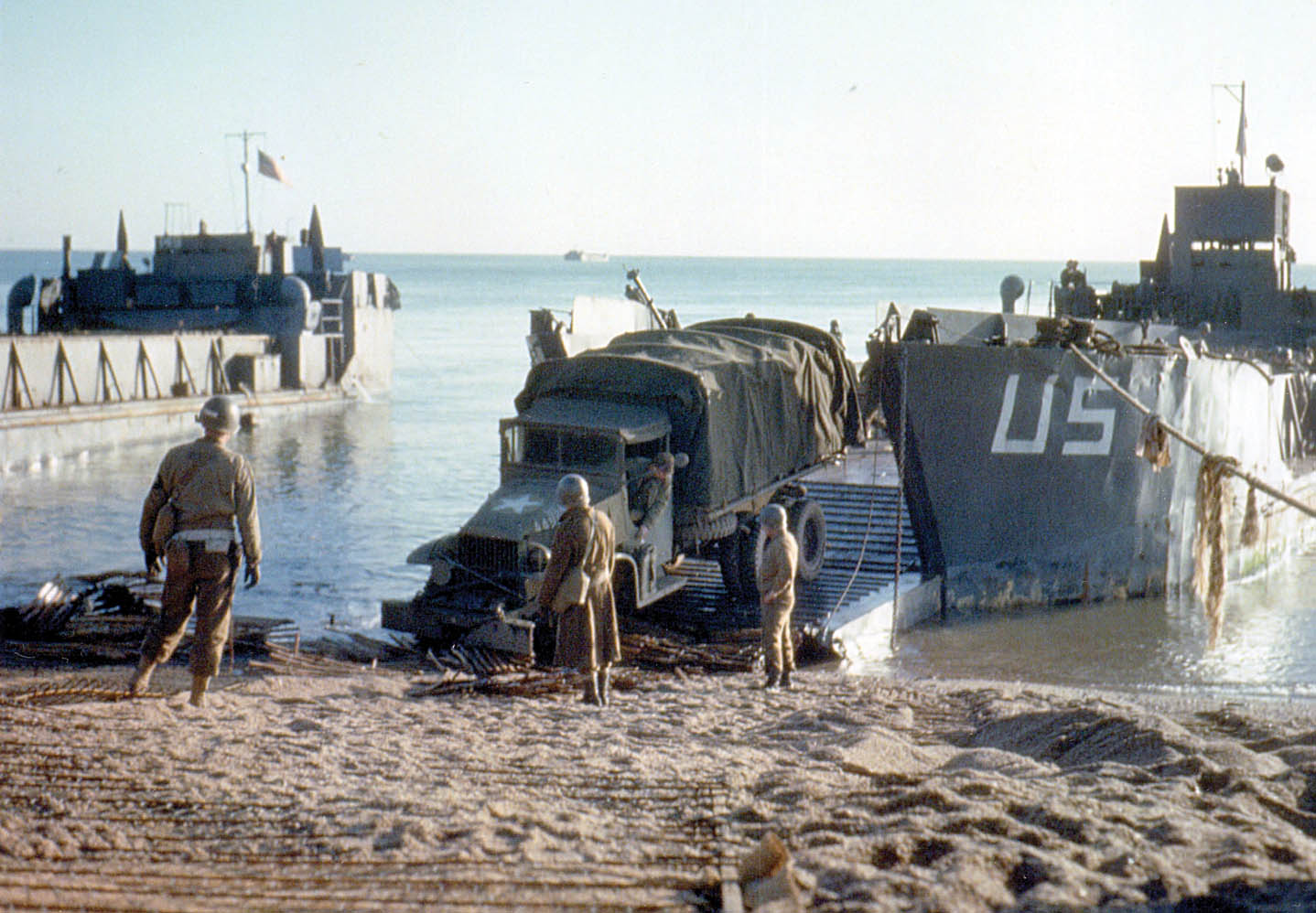

Full-scale practice landings for the D-Day invasion got under way in the early months of 1944. One of the biggest rehearsals was Exercise Tiger, planned at Slapton Sands in April for 23,000 men of Maj. Gen. Raymond O. “Tubby” Barton’s 4th Infantry Division and support elements. The operation commenced on Wednesday, April 26, when riflemen and tank, combat engineer, and medical troops were taken out into the choppy English Channel. The first assault wave stormed the broad Slapton beach, facing simulated machine-gun fire and even fake dead bodies, at dawn on the 27th. The landing was marked by “wild confusion,” with troops arriving in the wrong order, traffic jams, and a lack of senior naval officers to take charge.

The troops forming the second and third assault waves were loaded aboard eight hulking, flat-bottomed LSTs (landing ship, tank) with massive bow doors, each of which could carry 300 men and 60 vehicles straight onto a beach. Men, vehicles, and supplies were crammed into the 322-foot-long vessels, nicknamed “Large Slow Targets.”

E-Boat Raid on the LSTs

The opening phase of Exercise Tiger was watched briefly on April 27 by General Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme commander of the Allied armies, General Bernard L. Montgomery, Allied ground forces leader, and Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, the overall D-Day naval commander, but things started to go awry from the beginning. On that morning, Rear Admiral Don P. Moon, the U.S. naval commander of the exercise, postponed H-hour for 60 minutes, and some units of the 4th Infantry Division did not receive the message.

Royal Navy destroyers had been assigned to protect the LSTs, but owing to an error in the paperwork the landing craft and their escorts were on different radio frequencies and could not communicate. Further, one of the ships, HMS Scimitar, had to return to base at Plymouth after being holed in a ramming on April 26, and her captain was unable to inform the Americans. He asked for permission to rejoin the convoy but was refused. This left the rear of the “invasion flotilla” unprotected.

Commander Bernard Skahill was the U.S. officer responsible for the LSTs. Directing the flotilla from the bridge of LST-515, he had no way of knowing on April 27 that he was to be protected only by the destroyer HMS Saladin and the underarmed corvette HMS Azalea. The Saladin was 30 miles away and did not catch up with the LSTs until after 3 am.

During the night of April 27-28, the heavily laden LSTs—inadequately protected and vulnerable—and two pontoons of Admiral Moon’s 337-vessel Force U churned slowly through Lyme Bay, off the Dorset resort of Lyme Regis, heading for Slapton Sands, about 40 miles westward. Then, shortly before 2 am while the flotilla was 15 miles off the Dorset peninsula of Portland Bill, all hell suddenly broke loose when nine diesel-powered German E-boats from Cherbourg appeared on the scene. They were like foxes loose in a chicken coop.

Painted black and almost invisible, the raiders screamed across the dark water among the landing ships and fired streams of green tracer shells that spread panic and chaos. One of the enemy boats fired two torpedoes, and a sheet of flame leaped from LST-507. Fatally damaged, she started sinking as some of the 447 soldiers and sailors on board began throwing themselves into the sea. Men yelled, “We’re gonna die!”

Lieutenant James Murdoch, who survived the death of LST-507, reported later, “All of the Army vehicles naturally were loaded with gasoline, and it was the gasoline which caught fire first. As the gasoline spread on the deck and poured into the fuel oil which was seeping out of the side of the ship, it caused fire on the water around the ship.”

For Lieutenant Eugene Eckstam, “the greatest horror” was the screams of soldiers trapped in the “high, roaring furnace fire” where trucks were exploding on the LST’s tank deck. Commander Skahill saw the LST-507 inferno, but he had no idea what had happened because of an earlier order for radio silence. Worse was yet to come.

“Night of the Bloody Tiger”

Fifteen minutes later, two E-boats closed in on another landing ship. Two torpedoes slammed into the side of LST-531, and she started listing to starboard, rocked by explosions. Her demise was even swifter than that of LST-507. Emanuel Rubin, a crewman aboard LST-496, saw “a gigantic orange-ball explosion, like something from the movies, a flame like it had come from hell, with little black specks round the edges which we knew were jeeps or boat stanchions, or men.” Injured men screamed for help as they were thrown into pools of burning oil on the Channel surface.

Floundering helplessly in the black water and trying to calm panic-stricken men, Navy Corpsman Arthur Victor watched ammunition explode from LST-531’s bow “like a Fourth of July celebration” and “bodies flung in all directions like rag dolls.”

By now, confusion swept through the ambushed LST flotilla. Exercise Tiger, a dress rehearsal for the Normandy invasion only a month and a half away, had swiftly turned into a nightmare of blind firing, panic, and sudden death. One LST crewman said that the E-boats had the landing ships “trapped and hemmed in like a bunch of wolves circling a wounded dog.”

Confused soldiers shot at their own boats, believing they were firing at the Germans. Other GIs, unaware that they had been issued with live ammunition, thought that the explosions and flames around them were part of the exercise. Men drowned, and Sherman tanks and trucks sank.

Around 2:30 am, an E-boat loosed a torpedo at LST-289. Another explosion lit up the Channel waters, and the LST’s stern was severely damaged, but her crew managed to keep her afloat. A Royal Navy task group led by the destroyer HMS Onslow raced to the area, but the E-boats eluded it.

By 3:30 am, Commander Skahill decided not to risk losing more of his men, so he sent the remaining six LSTs back to port. Before doing so, one of his ship’s landing craft moved through the wreckage and picked up 45 survivors. When dawn broke, hundreds of soldiers were found floating upside down in the cold Channel waters. Improperly instructed, they had incorrectly placed their life vests around their waists instead of under their arms. The weight of their packs and equipment had forced their heads down into the water, and they drowned. Burns, shock, and hypothermia also took a toll. For these untried young American soldiers and seamen, their baptism of fire had come unexpectedly and six weeks early.

The initial death toll in the most costly wartime training disaster in U.S. military history was 441 Army and 198 Navy personnel, but another 110 soldiers were subsequently determined as killed or missing. The heaviest casualties occurred among quartermaster and valuable engineer companies. One of the largest losses of American lives in a single incident since the Pearl Harbor attack, it came to be known as the “Night of the Bloody Tiger.”

“We Were Told to Keep Our Mouths Shut”

When reports of the disaster reached General Eisenhower’s headquarters near Portsmouth, Hampshire, it was quickly decided that it should remain a secret in order not to undermine morale. Survivors were driven to sealed camps and warned not to breathe a word about what had happened. Eugene Carney, a 4th Infantry Division quartermaster, reported, “We were told to keep our mouths shut and taken to a camp where we were quarantined. When we went through the mess line, we weren’t even allowed to talk to the cooks.” Doctors were told not to ask questions when burned and wounded men reached military hospitals.

The genial, chain-smoking Ike had many worries in the weeks before the planned invasion, but now it was clear from the E-boat attack that the Germans had located the exercise and could easily infer the real Allied objective. Rumors were rife that one of the E-boats had scanned the waters with a searchlight and that several had cut their engines and hauled prisoners aboard. Among the missing were 10 officers who knew “BIGOT” security details of Operation Neptune, the naval phase of Overlord, and it was feared that if any had been captured the crucial D-Day element of surprise would be lost. Navy divers were sent out to retrieve dog tags, and eventually all 10 men were confirmed dead. SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) censored the incident to avoid alerting the enemy to its importance.

The security scare was ended, but not all of the dead in the Channel could be accounted for. Fearing the possibility of detection, SHAEF kept a close eye on the Ultra intelligence system to determine if the Germans were making any changes in their defenses that would indicate knowledge of Allied intentions. Within a week, Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler ordered that the Normandy coast be closely monitored and new defenses prepared. It turned out that these moves did not result from the Lyme Bay debacle.

An Unreported Disaster

The Slapton Sands exercise, with its death toll of 749, caused great alarm in the Allied military hierarchy. Ramsay called it “a flop” with “much to criticize,” and the U.S. Army’s official history recorded that “almost everything went wrong with this putative combined operation.”

Yet, if Slapton Sands reflected poorly on the American training and state of readiness for the imminent Normandy invasion, it also brought an indictment against the Royal Navy. Citing muddled communications, inadequate escort, and “an unfortunate series of oversights which began before the ships even left port,” a top-secret report charged, “Much of the blame for the high death toll in Exercise Tiger must lie with the Royal Navy staff at Plymouth…. The American LSTs were given incorrect radio frequencies, preventing contact with the Royal Navy…. The ships were carrying much more fuel than they needed for the exercise, so many of the men in the water suffered terrible burns.”

To safeguard the Overlord assault, General Eisenhower clamped a veil of secrecy over Operation Tiger. This was lifted in July, a few weeks after the June 6, 1944, invasion, when a SHAEF statement revealed what had occurred off Slapton Sands. Charges were made later of a cover-up by Ike and the War Department, although accounts of the tragedy eventually appeared in several publications, including official Army and Navy histories.

Nevertheless, in the subsequent weeks and months, the incident went unreported. Front pages, radio broadcasts, and newsreels focused on the Allied armies landing triumphantly on the five Normandy beaches, struggling through the tangled bocage country, liberating a delirious Paris, and pushing on eastward through France, Belgium, and Holland to the German border. The dead of Slapton Sands seemed to have been forgotten and denied their place in history, and the mystery of what happened there lingered. Many of the GIs’ bodies were never found, although some Devonshire residents reported having seen U.S. troops burying corpses in an unmarked grave in a farm field. Questions were raised but went unanswered for several years.

Wounded victims of Exercise Tiger had been treated at a U.S. Army field hospital in Dorset. The doctors and nurses were never told the causes of the men’s injuries and were ordered to maintain secrecy under threat of court-martial. One of the doctors there, Ralph Greene, who later became a Chicago pathologist, decided several years later to learn about Slapton Sands. Publishing his findings in the February 1985 issue of American Heritage magazine, he wrote, “When most of the remaining secrets of World War II were lifted in 1974 through the Freedom of Information Act, the entire story [of Operation Tiger] became available, but nobody bothered to report it.”

The Slapton Sands Relics

One wintry day in 1969, Slapton innkeeper Ken Small took a stroll along the windswept, crescent-shaped strip of coast after a severe storm had shifted shingle and stones. The burly former Royal Air Force corporal and policeman, who had moved south from Yorkshire in 1968, made a startling discovery. “All the shingle and stones had been washed away from the beach,” he reported, “and I started finding spent and live cartridge shells, shrapnel, U.S. Army insignia, and men’s gold signet rings.” Although he did not know it, he had stumbled upon relics from Exercise Tiger.

Three years after he had found the Slapton Sands relics, Small was told by a local fisherman that there was a submerged tank a mile offshore on which trawlers regularly snagged their nets. With his curiosity heightened, Small hired a diving team to investigate. Sixty feet beneath the English Channel surface, the divers located a U.S. Mark V Sherman medium tank of the 4th Infantry Division’s 70th Tank Battalion. With its 75mm gun facing the shore, it had rested there since the fateful night of April 27-28, 1944. A decade later, on May 31, 1984, the tank was finally hauled to the surface—just before the 40th anniversary of D-Day. Small recorded the event on videotape, which he readily showed to visitors at his inn.

Continuing to probe into the mystery of Slapton Sands, Small learned that the tank’s five-man crew had survived. So, in 1985, he attended a reunion in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, of the 70th Tank Battalion, and met the tank commander, Orris Johnson of Leeds, North Dakota.

The innkeeper’s crusade, meanwhile, prodded American officials into action, and Representative Byron sponsored a resolution calling for a memorial to the Slapton Sands dead. It passed Congress in January 1987, and a commemorative plaque was cast in Colorado to be placed near Small’s tank.

Finally, at a rain swept, 40-minute ceremony on November 15, 1987, the memorial was unveiled by Defense Department officials, Byron, Devonshire councilors, and Army officers. Small tearfully placed a poppy wreath on the plaque, a local band played the old Anglican hymn, Amazing Grace, a U.S. Army color guard presented arms, and a bugler sounded taps.

I live on Portland right next to the Verne prison and rumour has it that many of the dead from Op Tiger were hidden in the Tunnels beneath the prison. The tunnels were sealed in 1994. I have been trying to prove this for many years but so far have been unsuccessful.

Jon

While Admiral Don P. Moon participated in the Normandy landings, two months later he committed suicide while in Italy.