By Peter Suciu

While no one American city played a greater role in World War I than others, after a campaign by local residents, Kansas City, Missouri, was chosen as home to build the nation’s memorial for those who gave their lives in what was hoped to be the war to end all wars. Although sadly it was not to be the final war, the effort by the Kansas City residents eventually made possible establishment of the National World War I Museum at Liberty Memorial.

The guns had only just fallen silent in late November 1918 when the first initiative began for a memorial for what had been the greatest conflict to date. This led to a community-based fundraising drive in 1919 that raised more than $2.5 million in less than two weeks and drew international attention as a result. The historic site of Penn Valley Park was developed in 1904, on land over which the Santa Fe Trail had passed half a century earlier, and was chosen as the location for the Liberty Memorial. Located on what was then the outskirts of downtown Kansas City, it provided a vast open space for a large memorial tower and field of remembrance.

The site was dedicated in 1921 at an event that was attended by military leaders of the five main Allied nations—this being the first time these five were ever together in one place. These men were Lt. Gen. Baron Jacques of Belgium, Admiral Earl Beatty of Great Britain, General Armando Diaz of Italy, Marshal Ferdinand Foch of France, and General John Pershing of the United States.

A national architectural competition conducted by the American Institute of Architects was held for monument designs, and those of American architect Harold Van Buren Magonigle were chosen. Fittingly, the New Jersey-born architect is best remembered today for his memorials. In addition to the monolithic Liberty Memorial, he also designed the McKinley Memorial Mausoleum in Canton, Ohio, and collaborated on the Monument to the USS Maine, which stands today in New York City’s Columbus Circle near the entrance to Central Park. The primary sculptor of the memorial was Robert Aitken, whose work also included the Dewey Monument in San Francisco.

After three years of construction, the Liberty Memorial opened on November 11, 1926—eight years to the day after World War I ended. It was dedicated by President Calvin Coolidge, who noted, “The magnitude of this memorial, and the broad base of popular support on which it rests, can scarcely fail to excite national wonder and admiration.”

That could have been the end of the story, and while the impressive 217-foot tall structure lights the night sky, it was long felt that more could—and dare should—be done to remember those World War I veterans. Over the years came calls for a World War I museum, and the memorial faced the ravages of time. The monument, which lacked any significant space for a large museum, was eventually closed to the public due to neglect and lack of interest outside Kansas City.

However, all this changed for the good, when in 1988 Kansas City voters overwhelming passed a sales tax to raise money for the memorial’s restoration, while private funding supplemented efforts. The first major restoration in more than two decades was completed in 2002. It was two years later in 2004 when the dream of a museum actually became a reality. That year saw two major milestones, including the passage of a $20 million bond initiative to fund the construction of a new museum, and President George W. Bush’s signing into law a bill that designated the Liberty Memorial as the National World War I Museum, which it was officially designated by the 108th Congress. In 2006, the same year that the museum opened to the public, the site was deemed a National Historic Landmark.

It is worth noting, too, that today the official designation is actually The National World War I Museum at Liberty Memorial, but efforts are underway to make it The National World War I Museum “and” Liberty Memorial, thus linking the two together permanently.

“From its inception, the Liberty Memorial has been a national focal point for honoring those who served in the First World War,” said Doran Cart, curator of the National World War I Museum. “Additionally, the museum was regarded as the best repository very early on with the U.S. Navy donating the torpedo, the Imperial Japanese government donating materials, the French donating fragments of the Reims Cathedral damaged in the war, and many personal items from those who served, all donated before 1926.”

Visitors to the museum immediately will note that it does not take away from the effect of the memorial, as the new subterranean facility greatly expands but does not change the overall effect of the original main deck exhibition hall and memory hall.

Additionally, anyone entering the National World War I Museum will cross the Paul Sunderland Bridge, an impressive yet somber reminder of the price of war. The glass ceiling provides a view of the memorial, while under the glass bridge are 9,000 poppies, each representing 1,000 combatant deaths totaling the nine million casualties from the Great War. This was, of course, inspired by the famous World War I era poem, In Flanders Field, written in 1915 by Canadian soldier and poet John McCrae.

This entry leads into the main exhibit floor, which is divided into three main galleries, the first covering the years 1914-1917. This gallery, which features numerous uniforms, equipment and even objects that were used in daily life in the trenches, offers a monthly account of the time before America entered the war. There are multiple recreations of Western Front trench lines, as well as air war and war at sea galleries, which even include a U.S. Navy built scale replica of a German U-boat. From the first gallery, visitors travel to the Horizon Theater, where a 15-minute program shows America on the brink of the conflict and ponders the question, “Should America enter the war?”

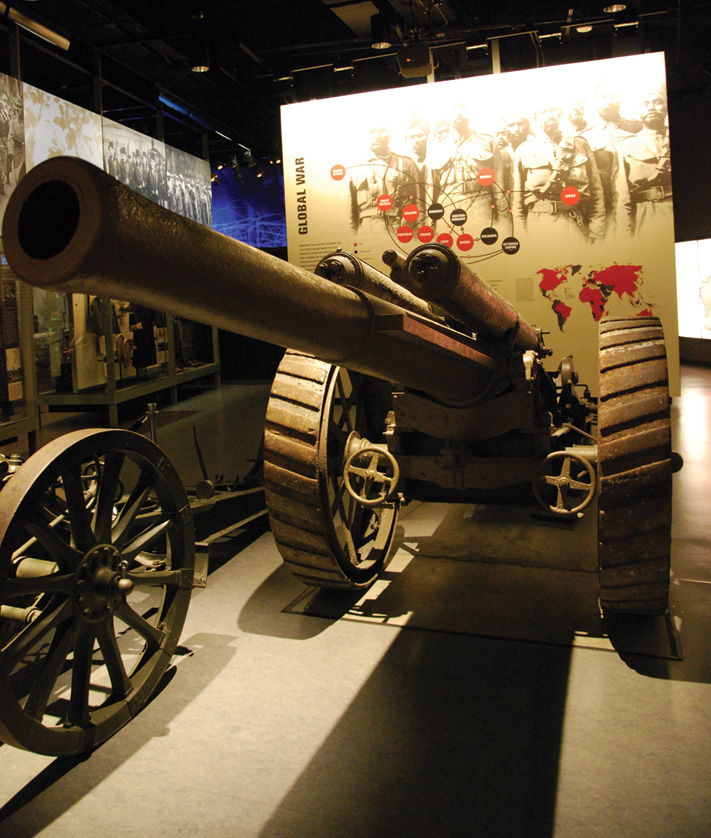

This follows the Years 1917-1919 gallery, which contains numerous artifacts used by the soldiers who went “Over There.” These include many uniforms, a French-built American Renault FT-17 tank, and a crater model that represents a building as if destroyed by artillery. A highlight of this gallery is also the women’s role in the conflict.

While the museum may tell the story of one of the worst conflicts in the history of the 20th century, it is still very much in the 21st century with state-of-the-art interactive exhibits and features. These interactive exhibits and features allow visitors to create their own propaganda poster, which can even be e-mailed to a friend, or to take digital quizzes and get detailed facts on the weapons and equipment used in the war. Additionally, period recordings and music are provided to further set the mood and immerse the visitor into the time of the conflict from nearly 100 years ago.

The outer wall of the new museum is home to the Portrait Wall, which portrays the personal sacrifices of those who served in the war, and this is regularly expanding to contain new material.

The Memory and Exhibit Halls, which are part of the original structure from 1926, also offer additional items of interest. Rotating galleries are held in the Exhibit Hall, while the Memory Hall is used primarily to offer a personal look at the war with items that are tied to specific individuals.

Additionally, visitors can take an elevator ride to the top of the 217-foot tall tower, which offers stunning views of Penn Valley Park, the nearby Federal Reserve, and of course the Kansas City Skyline. The Walk of Honor on the ground level further offers a lasting remembrance, carved in granite, of those who gave their lives and must not be forgotten.

Keeping with the theme, the museum’s small but quaint café—aptly named the “Over There Café”—offers simple fare, but unlike other museums, which seem more like a fast food restaurant, this one actually makes dishes to order. Most of the dishes are named for figures from the war but still done in a respectful way.

Artifacts in the permanent collection truly make this a world class museum and, sadly as with many institutions, only a portion is on display. Only about seven percent of the entire collection is on view through the new museum halls, as well as the Exhibit and Memory Halls. Much of the additional collection is housed within the facility.

The 20,000-square-foot research center, which is a level below the new museum, is available for those working on special studies and can be visited with special permission. Additionally, the public research room is open daily to allow visitors to access the library holdings. While much of the collection is therefore unavailable at most times, fortunately the museum’s staff works hard to make sure that crucial items are loaned out at times.

“The museum regularly loans materials to other museums for special exhibitions,” said Cart. “We currently have a number of objects on loan and on exhibit at the Woodrow Wilson Home and Museum in Staunton, Virginia, as one example.”

As with other institutions, the collection also is continually growing, thanks in no small part to the efforts of Cart and contributions from private collectors. In many cases, standout items get front and center treatment.

“When the museum acquires new materials, like the Hindenburg tunic and cap, then those we try to get on exhibit as soon as possible,” said Cart. “Other materials that tell a good story are also rotated onto exhibit. Some organic materials do need to ‘rest’ so they are rotated off on a regular basis and similar items put in their place.”

Moreover, the museum could see growth in its future as well. Cart told Military Heritage that there are additional plans for a large, special exhibition space to be built on the east side of the main museum floor, hopefully for the war’s centennial in 2014. This would certainly increase what could be displayed for visitors to see.

Even with so many standout items on display, Cart noted that a few hold a special place in his heart and certainly draw a share of attention as well.

“The Model 1917 Army Harley Davidson motorcycle, the trench experience vignettes, the French 75mm gun, and the women’s uniforms,” he names as just a few items that seem to remain popular with visitors. Of course, there is that Renault FT-17, which was painstakingly transported to the museum. This tank reportedly has ties to Kansas City, the home to its World War I era crew.

However, even with these artifacts, Cart did note that there are still many items the museum would like to see added to its permanent collection in the years to come.

The wish list includes “an original airplane from the war; German, French or British vehicles, important persons’ uniforms, and … German U-boat materials” to name just a few.

Given that the 100th anniversary of the Great War is approaching, many items have circulated, and donations have made the museum’s collection all the greater.

As that major anniversary approaches, Cart noted that the National World War I Museum will be ready with commemorations and will look back at what so many fought and died for all those years ago. “We will have numerous special events and activities to commemorate the centennial. While there are no specific plans to share at this time, we plan to host many events here at the museum and partner with others to do the same throughout the country.”

The museum is located at the corner of Main Street and Memorial Drive. It is closed on Mondays, as well as Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, Christmas Day and New Year’s Day. It is operated in agreement with the Kansas City, Missouri Board of Parks and Recreation Commissioners.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments