By David Alan Johnson

The first word of the incoming Luftwaffe raid arrived at about 10:45 p.m. on the night of Saturday, May 10, 1941. Air Marshal Sholto Douglas was in the Filter Room at Fighter Command Headquarters in Stanmore, Middlesex, when the telephone call came through. The message was short and to the point: “There’s something big on tonight, sir.”

Radar stations all along the coast—at Pevensey, at Rye, at Ventnor on the Isle of Wight—had been picking up the German bombers for the past half hour, while the planes were still over France. During the next 25 minutes or so, more and more V-shaped blips of light began appearing on radar screens. At Ventnor, the count quickly increased from 20-plus aircraft, to 25-plus, and then to over 30. Every other radar station was also picking up enemy aircraft approaching the south coast in ever-increasing numbers. The message received at Fighter Command Headquarters was absolutely correct; the Luftwaffe was sending something big, and the target was London.

The Blitz against London had begun over eight months earlier, on Sunday September 7, 1940. Between September 7 and November 2, the city had been bombed for 57 consecutive nights. London’s City District had been entirely burned out on the night of December 29. During the month of April 1941, the Luftwaffe conducted two heavy raids, which were remembered by Londoners as “the Wednesday”—April 16—and “the Saturday”—April 19. On this night, May 10, the bombers were returning for another maximum effort.

Shortly after Air Marshal Douglas received his telephone message, the air-raid sirens began to sound throughout London. A fire watcher on the roof of a City firm made a quick entry in the logbook: “Air raid alert, 10.48.” Even after eight months of bombings, the sirens still made Londoners tense up; there was no such thing as a “routine” alert. A woman from the Paddington area remembered, “Every time I heard the sirens, my nerves went into a knot. We never knew whether an attack was going to be a small nuisance raid or a massive effort. It only took one bomb to kill you. I was always frightened stiff by those sirens.”

The first bombs to come down on this Saturday night were dropped at 11:05 p.m. by the pathfinders of Kampfgeschwader (Bomb Wing) 100. KGr 100 had been assigned the job of dropping thousands of two-pound incendiary bombs at the beginning of the raid, creating a luminescent aiming point for the rest of the bomber fleet. KGr 100, the “glamour boy” unit of the Luftwaffe’s bomber fleet, was famous for having the best pilots and air crews in the Luftwaffe. Nicknamed “Fire Raisers,” the group was staffed entirely by hand-picked officers and crew, most of whom had been in the Luftwaffe since before the war and all of whom had many hours of combat flying.

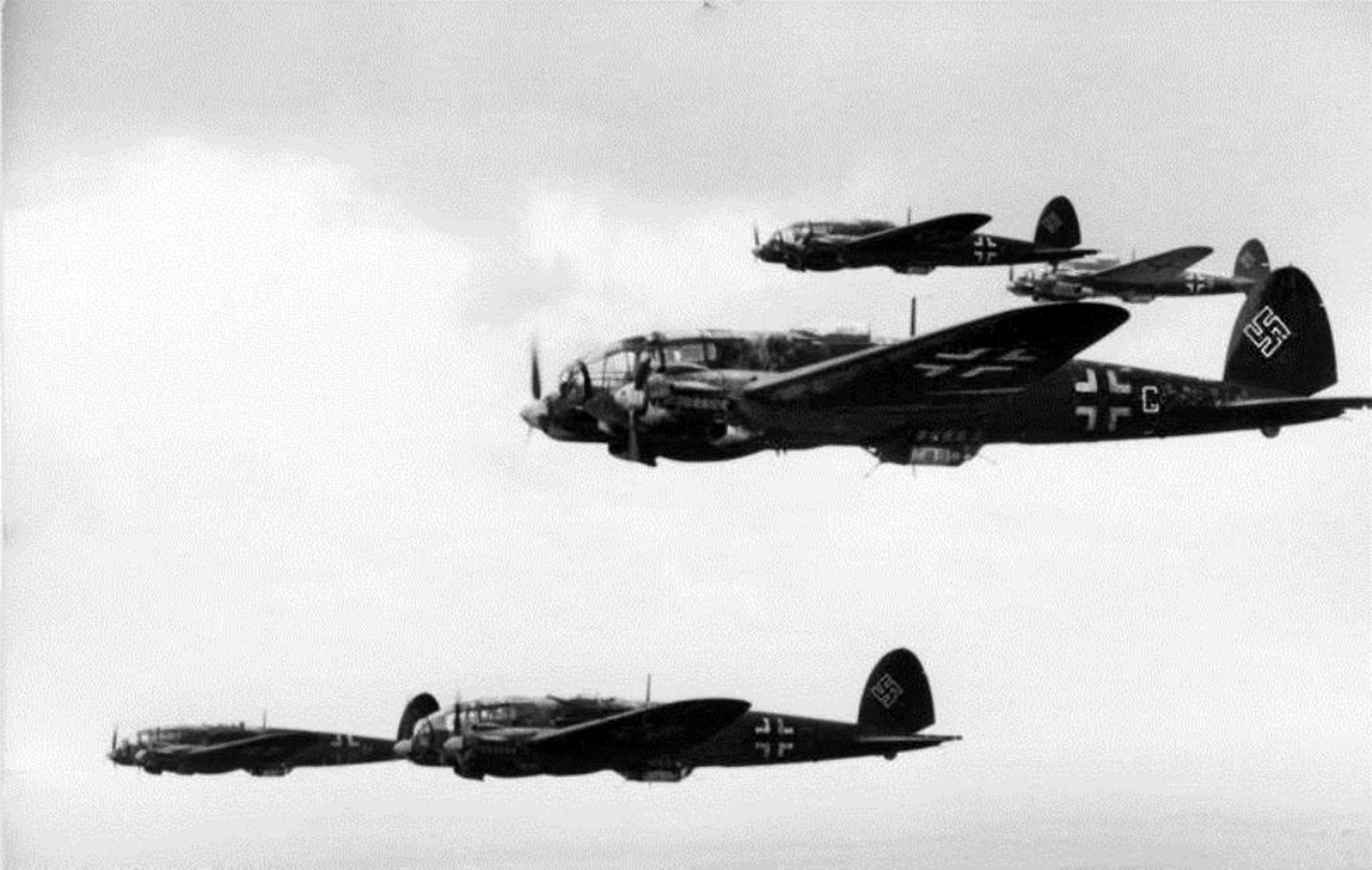

KGr 100’s complement of 20 Heinkel He-111 bombers crossed the English coast at 10:45, just as the night’s maximum effort was beginning, and had been registering on British radar screens ever since they had taken off from their base at Vannes, in Brittany. Twenty minutes later, the group’s bomb aimers scattered their incendiaries across London, all the way from Waterloo Station to the docks beyond Tower Bridge. Each bomber carried eight canisters of the foot-long incendiaries; each canister, called a “Molotov Breadbasket,” held 36 firebombs, for a total of 286 incendiaries per bomber. In total, the group would drop nearly 6,000 of the small but lethal bombs.

The incendiaries did their job with frightening efficiency, punching their way through roofs and igniting hundreds of widespread fires. The individual fires spread out across streets and alleyways and began merging into major conflagrations within a quarter of an hour. Roof spotters throughout London began telephoning their first fire reports before 11:30. Blazes could be seen all across central and eastern London, and they appeared to be growing in intensity. On a factory roof in northwestern London, a fire watcher told an operator in the control center, “I can see a very large fire over to the east.” This was one of hundreds of similar reports being submitted across the city.

By about 11:30, all 20 of KGr 100’s Heinkels had dropped their bombs and were turning back toward their home base in Brittany. Captain Friedrich Aschenbrenner could be well-satisfied that his men had done a thorough job of lighting up the target. Several large fires had been set, including a massive blaze east of Tower Bridge, which was clearly visible for many miles. Aschenbrenner ordered his radio operator to send a message to Field Marshal Hugo Sperrle, the commander of Air Fleet Three, at his headquarters in Paris: the target was well alight and well marked for the rest of the incoming bomber force.

By 11:00, most of Field Marshal Sperrle’s bombers had either already left their bases or were preparing for takeoff. They included Kampfgeschwader (Bomb Wing) 27, based at Dinard in Brittany; KG 54 at Evereux; Lehr Geschwader 1 at Orleans; KG 51 at Orly, near Paris; and KG 4 at Eindhoven, Holland.

At British Fighter Command Headquarters, the plots kept coming in at a steady rate. Ventnor was plotting 20-plus hostiles still over France; Pevensey had another 15-plus just crossing the Channel coast. From the controller’s gallery overlooking the huge map of the British Isles, Air Marshal Douglas watched as the WAAFs—members of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force—marked these plots on the map. Red metal arrows, representing the locations of incoming enemy aircraft, were maneuvered into position by long, magnet-tipped plotting rods. As the stream of bombers advanced toward London, the red arrows were also moved northward toward their targets on the map.

Residents of London did not need anyone to tell them where the Luftwaffe’s bombers were heading. In scattered locations throughout the city, roadways and rooftops were being sprinkled by shrapnel from bursting antiaircraft shells, and searchlight beams darted across the night sky looking for the intruders. American journalist Quentin Reynolds was astonished by the noise made by the incoming airplanes. “Christ,” he said to a fellow reporter, “it sounds like there are hundreds of them.”

At this stage of the raid, there were not yet hundreds of bombers over London, but there soon would be. So many contacts were being made by the radar stations that the blips on the screens merged into one massive splotch. The WAAFs at Fighter Command Headquarters were no longer receiving detailed reports; the stations could only announce “massive plots.” Radar defenses were being overwhelmed by the number of enemy aircraft crossing the Channel.

Even though the raid had just begun, fires were already burning out of control and spreading fast. In the vicinity of Waterloo Station, incendiary bombs had already set several good-sized blazes. At Fields Candle Factory, fire spotters were doing their best to put out the incendiaries that landed on the building’s roof, but the bombs kept falling. They were determined to hold on and save their factory, and so far, they had managed to smother each bomb with sand before it could do any damage. But at about 11:40, a London Fire-Brigade officer telephoned to advise that two nearby water mains, one at York Road and the other at Waterloo Road, had been fractured by high-explosive bombs. The entire area would be without water to fight the fires.

Residents living near Finsbury Circus had a different problem: Two parachute mines had landed in the vicinity. A fire watcher had seen them come down, slowly and silently, by parachute, and immediately threw himself flat on the ground. The mines, which were actually anti-shipping weapons, were eight feet long and contained 1,500 pounds of high explosives. When one of them exploded on dry land, the concussion was devastating—the blast could demolish an entire row of houses and still have enough power to smash windows two or three streets away.

When the fire watcher rose to his feet after the explosion, he found himself looking at a scene of absolute devastation. Sixty houses, a brewery, a barrage-balloon site, and several other buildings had been shattered; 60 people had been killed by the blast, and about twice that many had been seriously injured. Several other parachute mines came down in other sections of London and created their own havoc.

By midnight, it had become evident that this raid was not directed at any particular district, but that all of London was the target. The attack still seemed to be gaining momentum, hitting areas that had not been bombed earlier in the attack. Reynolds went up on the roof of the Savoy Hotel to see the fires and thought the scene was like something out of an epic Hollywood film. A man watching the attack from Hertfordshire, about 20 miles north of London, was shocked by its intensity. The explosions had been going on for what seemed like hours. “It’s that bastard Goering,” he said. “He’s really lost his temper.”

Colonel Paul Weitkus of KG 53 was not losing his temper, but he was concerned about British night fighters. He had taken off from Lille at about 11:30 p.m. and had flown straight to London with no interruptions. But he knew the fighters were out there somewhere; there was a full moon, and German bombers made an inviting target on such a well-lit night. The antiaircraft fire was heavy, but not accurate; it rarely was. His target was the Victoria Docks, east of the Tower of London. He intended to put his bombs— a mix of high explosives and incendiaries—directly on target and get back to base before either the flak or the fighters could get to him.

Weitkus and his crew could see the fires of London before they crossed the English coast. As they neared the city, the fires became more vivid and more widespread. Everything along the Thames, on both sides of the river, seemed to be burning. Even the river itself seemed to be on fire—it was the color of bright, red-hot coals as far downriver as he could see. The Victoria Docks were easy to spot—brilliantly illuminated, as though by hundreds of floodlights. He had been to London on many raids since the Blitz last September, but these were the most intense fires he had ever seen. It looked as though nothing would survive this attack.

The bomb aimer, lying prone on his stomach in the nose of the aircraft, manipulated a series of switches on the bombsight. Occasionally, he would call out instructions to Weitkus: “Come left a few degrees. That’s good. Now steady …” But he kept staring into the sight, adjusting the dials. Finally, he pushed a button at the end of a long cable, releasing the bombs. The Heinkel suddenly jumped into the air, over 1,000 pounds lighter, while its load of high explosives plummeted toward the docks. “Bombs gone!” crackled his voice over the crews’ headsets.

During the next few minutes, the bomb aimers in the other 19 Heinkels of Oberst Weitkus’ group followed the same routine—last-minute adjustments in course, release of the bomb load, and “Bombs gone!” With all bombs released, there was nothing more to do except turn for home. The radio operator notified Paris that the target had been bombarded successfully. The bomb aimer returned to his role as navigator and set a course back to Lille.

Weitkus would make it safely back to base, but at least four German bombers had already been shot down by British fighters. Forty fighters were spread out between London and the south coast. This included everything from twin-engine Bristol Beaufighters, specially equipped with AI airborne radar sets, to Supermarine Spitfires and Hawker Hurricanes—day fighters without any radar. The night fighters did not have much of a chance of intercepting an enemy bomber even with their radar, but the Spitfires and Hurricanes had almost no chance at all.

But Air Marshal Douglas was not discouraged. Any mention of the RAF’s fighters engaging enemy bombers made good news headlines and was good for morale. He was also convinced that the fighters were having an effect on the enemy bombers, no matter how many bombers were being shot down or where they were being destroyed. “It does not matter where the enemy is shot down so long as he is shot down in large numbers,” he said. Or even in small numbers, especially on a night like this, when the map of the filter room was covered with red arrows.

One red arrow in particular was causing concern. Slightly before 10:30, the filter room received a telephone call that a single aircraft had crossed the coast northeast of Alnwick, Northumberland. Two fighters were sent to intercept the mysterious airplane, but they quickly lost track of it—the aircraft was traveling over 300 miles per hour. No one had any idea what the airplane was doing that far north, or even whether it was British or German. There were no friendly aircraft in the vicinity of Northumberland, but it could not possibly be a German bomber, either—no Luftwaffe bomber could reach speeds anywhere near 300 miles per hour. After staring at the red arrow for several minutes, a decision was reached: “Slap an X on it,” marking the contact as “unknown.” It might just be a friendly fighter in trouble.

But Sholto Douglas was not satisfied simply to call the mystery plane “unknown” and leave it at that. He issued an order, “Find out what it is—what it’s doing.” As he spoke, WAAF plotters continued to push the arrow farther to the north, toward Scotland. The first solid clue regarding the airplane’s identification came from an Observer Corps post in the north of England. “We’ve got a visual at one hundred feet;” it was a Messerschmitt 110 twin-engine fighter, flying north toward Edinburgh.

Sholto Douglas did not believe it. “Impossible,” he said. “No Messerschmitt would have the fuel to get to Edinburgh and back. Get another fix on it.” A few minutes later, a telephone call from the Observer Corps confirmed the earlier report—the airplane was a twin-engine Messerschmitt flying at extremely low altitudes, sometimes as low as 50 feet.

“Get the fighters up after it,” the air marshal ordered. But that was the last clear message regarding the mystery aircraft. Shortly after the order was given, the airplane was identified as a Boulton Paul Defiant, a single-engine RAF interceptor. Next, an Observer Corps station near Glasgow reported that the airplane had been shot down. But when fighter control in Scotland was contacted, no one knew anything about any airplane being shot down. That was the last report Douglas heard concerning the mystery plane; at about 11:20 p.m., a WAAF removed the red arrow from the map. But Air Marshal Douglas had the feeling that the incident was not over.

At his headquarters in the Hotel Luxembourg in Paris, Field Marshal Sperrle could be well-satisfied that his bombers seemed to be inflicting maximum damage to London. According to the reports he had been reading, entire areas within the city were burning out of control. The eastern section of London had been especially hard hit; fires were spreading for miles all along the River Thames. And the night was far from over—the attack was scheduled to go on until daybreak. After looking at the reports from the bombers, the field marshal decided that he might as well go to dinner; there was no point in staying at headquarters. He would get a full account of the raid in the morning, after it was over and all the bombers had returned to base.

Members of the London Fire Brigade did not need any news dispatches to tell them how desperate the state of affairs had become. Those at work in the middle of the fire zone were surrounded by flaming buildings; the situation looked to be getting steadily worse with the passage of time. The red, shadowy streets played tricks on the eyes. In the rose-colored twilight, firemen tripped over the straggling lengths of firehose. Side streets were entered with caution; fallen beams and huge chunks of debris went unseen in the half-light.

Water could be as much of an enemy to the firemen as the fires themselves. Under high pressure, darts of water from a loose coupling could hit a fireman in the face and temporarily blind him. Moisture on the outside of a fire hose acted like glue for ground glass, creating a hazard for a fireman’s hands. A brass hose nozzle, which weighed several pounds, could become a lethal weapon if it slipped out of a fireman’s grasp, lashing out and breaking an arm or fracturing a skull as neatly as a club.

Once in a while, an unintentionally funny incident would ease the tension. At the height of the attack, a civilian walked into an Air Raid Precaution (ARP) post carrying a bucket of water. “I have a bomp in my bucket,” he proudly announced in a heavy Eastern European accent. He proceeded to reach into the bucket and produce a chunk of white metal that had been the core of an incendiary bomb, displaying it for all to see. The wardens were not impressed. They advised the man to take his bomb to a nearby disposal center, but he paid no attention—it was his bomp and he intended to keep it. Having shown his trophy to the officers, the man walked out of the station. Apparently, he was traveling from ARP post to ARP post to show off his prized possession. The wardens just laughed and shook their heads as they watched him leave. It was the only funny moment they had all night.

At Fighter Command Headquarters, Air Marshal Douglas was also shaking his head. About an hour and a half after the mysterious German aircraft disappeared over Scotland, the operations room received a telephone call from an Observer Corps post near Glasgow. The message was startling to the point of being unbelievable: “We’ve got the pilot of the Me 110, sir. He admits he’s Rudolf Hess and he wants to see the Duke of Hamilton.”

It was a fantastic story. Rudolf Hess was Deputy Führer of the Third Reich—in the entire Nazi hierarchy, only Adolf Hitler and Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering outranked him. And he was now being held prisoner in Scotland—he had bailed out of his specially modified Messerschmitt after it had run out of fuel; he had not been shot down. He was asking to speak with the Duke of Hamilton, who lived on an estate nearby. Air Marshal Douglas was absolutely dumbfounded.

After all the facts were in, it turned out that Hess had flown to Scotland with a peace proposal—he wanted Britain and Germany to join forces in an offensive against the Soviet Union and thought that the Duke of Hamilton had the power and influence to persuade the British government to accept his plan. He had met the duke at the Berlin Olympic Games in 1936 and had convinced himself that the duke had the connections within the government to turn his idea of an Anglo-German alliance into reality. Instead, Hess was taken into custody and remained a prisoner for the rest of the war. After the war, he was tried by the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal and sentenced to life imprisonment.

After the mystery of the phantom Messerschmitt 110 had been solved, Air Marshal Douglas once again turned his full attention to the Luftwaffe’s determined effort against London, which still looked to be increasing. From the balcony overlooking the giant map of England, he watched as the red arrows moved northward toward London like a swarm of insects. There was no letup in the number of incoming enemy aircraft. Even after 3:00 a.m., the arrows continued their journey from the Channel coast toward their targets. It seemed that the attack was never going to end.

One of the metal arrows represented the Heinkel flown by Paul Weitkus of KG 53. Colonel Weitkus had returned to his base at Lille at about 1:45 a.m., after dropping his bombs on London. He’d sent a message to Luftwaffe headquarters in Paris, “Mission accomplished,” and headed for home. But when he landed, Weitkus was informed that he would be making a second trip that night; he was told to make certain that his Heinkel was refueled and to prepare for another sortie.

Weitkus was not happy about going back to London for a second time; he knew that British night fighters were in the air south of London and had heard that several bombers had been shot down. But the mechanics and armorers were already preparing his Heinkel for the trip. He decided to have something to eat before takeoff. It occurred to him that if he made it back, he would be landing just in time for breakfast. Like Sholto Douglas, it seemed to him that the attack would never end.

Residents of London had the same feeling—the night would never end, and the bombs would never stop falling. At the fashionable Alexandria Hotel in Knightsbridge, all of the guests had been escorted either to the lounge or to the air-raid shelter in the basement. The hotel was a large, six-story building and seemed secure enough, but it was always prudent to take every precaution. There were those who refused to come downstairs, of course; they were not about to give up their beds and their night’s sleep just because some bloody Germans were making a damned nuisance of themselves!

One of the hotel’s porters was on his way to the upper floor to rouse another porter out of bed. Going up six flights of stairs was a long climb; he decided to take the lift instead, even though he had been warned never to take the lift when an air raid was in progress. He stepped into the small passenger lift and pressed the button for the sixth floor.

Two 550-pound high-explosive bombs struck the hotel almost simultaneously. No one remembered hearing an explosion, although all of the survivors mentioned that the entire building shook violently. All the lights in the hotel went out; guests groped their way through the darkness, which was made even more impenetrable by the thick plaster dust that seemed to be everywhere. Half of the main lounge collapsed into the basement and dumped everything in the room—tables, chairs, lamps, clocks, books, even the stairway to the upper floor —down onto the shelterers below. One of the bombs struck the passenger-lift shaft, killing the hotel porter instantly and collapsing that section of the hotel. After the noise of the blast faded away, other sounds could be heard—the pounding on doors of the guests who were trapped in their rooms, the thudding of beams and other debris cascading down from upper floors, the cries of the wounded as they attempted to escape from the wreckage all around them.

Some of those who were fortunate enough to survive were surprised to find that the hotel had been so seriously damaged. A pair of long-time guests looked up from the ground floor and could see moonlight where there used to be five more floors. And there were those who kept on doing what they always did. A middle-aged couple made a habit of sitting on the same sofa in the main lounge every night; they never said very much. The woman always had a slight half-smile on her face; her husband sat beside her. Tonight, the couple was in their usual spot in what was left of the lounge, sitting on their sofa. The woman was covered with dust but still wore the same half-smile. Her husband sat beside her in his usual place. The only difference tonight was that he was dead, killed outright by the explosion.

A few miles to the east, some of London’s most famous landmarks were experiencing their own ordeals. The roof of Westminster Abbey had been set alight by incendiaries, and firemen were discovering that putting out the fires presented a major challenge—the roofing timbers were 130 feet above the floor and difficult to reach from outside the building. But the firemen managed to extinguish the fires, and the abbey was saved, even though the church’s lantern fell with a tremendous crash at about 1:00 a.m. Just a short walk away, the Houses of Parliament were not as fortunate. The House of Commons was blazing out of control; the fires spread throughout the chamber via the heating ducts, and there was not much the Fire Brigade could do to save the Commons Chamber. The best they could hope to accomplish was to keep the fire from spreading through the rest of the complex. The House of Lords had been struck by a firebomb, which passed through the roof of the chamber without exploding. An incendiary bomb also struck the bell tower and broke all the glass on its south face, but the well-known clock was not damaged, and the bell, Big Ben, continued to chime every quarter-hour.

Firemen were able to stop flames from destroying nearby Westminster Hall; the fires never were able to gain a foothold there. Putting out the small fires turned out to be relatively easy once the firemen were able get inside the ancient hall. The problem was that the main entrance had been locked, and nobody could find the key. The officer in charge did not want to chop down the door with fire axes—it was several hundred years old—so a Member of Parliament who had dropped by to visit the scene did the job himself. He informed the firemen that as a Privy Councilor, he had the authority to destroy the centuries-old door. Before anyone could say or do anything, the MP grabbed an axe and began chopping.

Once they were inside the hall, firemen trained their hoses on the burning roof beams and soon had them extinguished. The visiting MP was gravely concerned about the fate of the ancient hall, which dated from the year 1097, and encouraged the firemen do everything possible to save it: “Remember the building is a thousand years old. It must be saved.” But the officer in charge was more concerned with the safety of his men and was not impressed with the antiquity of the hall. “Never mind if it’s a thousand years old,” he said, “don’t risk your bloody necks if it gets dangerous.”

Word reached the firemen that Big Ben had been destroyed, a piece of news that put everyone in a sullen mood. But Westminster Hall is close enough to Parliament that the firemen could hear the famous clock ring the quarter-hour, which put their minds at ease.

The Luftwaffe attack was not letting up, and the fires showed no signs of dissipating, but the enemy did not have everything his own way. By the early morning hours, about 10 bombers had been brought down by RAF fighters, and Pilot Officer (P/O) Andrew Humphrey of No. 266 Squadron was about to shoot down two more bombers himself. P/O Humphrey took off from Wittering aerodrome at about 2 a.m. He discovered a Heinkel near the coast of Essex and managed to close to less than 100 yards of the bomber before opening fire. Because he was flying a Spitfire and did not have the benefit of radar, P/O Humphrey needed to get to within visual range before he could be absolutely sure of his target. The bomber blew apart, temporarily blinding him; he instinctively threw his fighter into a sharp turn—probably the tightest turn he ever made in his life—and just missed crashing into the burning remains of the Heinkel.

Pilot Officer Humphrey managed to recover his night vision after a few minutes, but he had no real idea where he was. He knew that he was over the North Sea off the coast of Essex but did not know how far off the coast he was. He was probably still dazed from his encounter with the Heinkel and decided to continue on his present course. Eventually, Humphrey spotted the landing lights of an airfield and suddenly realized that he had flown completely across the North Sea. He watched as a Heinkel took off from the runway on its way to London. Immediately, he pushed the Spitfire’s stick forward and began diving toward the German bomber. He could see his tracers hitting his target as soon as he began shooting, but he was suddenly shaken by an episode of vertigo just before the Heinkel crashed into the ground. As he tried to regain his equilibrium, Humphrey began to climb. Less than a minute later, he saw another potential target, a Messerschmitt 110, and dove at the unsuspecting fighter. But after firing only a few rounds, Humphrey heard the telltale sound of compressed air coming from the Spitfire’s guns—he had run out of ammunition.

The time was about 3 a.m. P/O Humphrey had run out of ammunition, was running out of fuel, and did not know where he was. Not knowing what else to do, he radioed his base at Wittering to ask for a course to take him back home. “I only know I’m heading southwest,” he said, “and I think I’ve shot down two Heinkels.” The controller at Wittering was not sure where young Humphrey was, either—it was either Holland or Belgium—but he gave the pilot the vector he needed to fly back to base. For his adventures on the night of May 10, Andrew Humphrey was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. According to his DFC citation, “This officer has performed splendid work as a night fighter pilot.”

From a distance, the London fires seemed to be a single mass of red flame. But the firemen and roof spotters within the fire zones throughout London could see an entire kaleidoscope of colors. Every building burned with its own unique shade, depending upon what was burning inside. Packing cases, as well as bedding and furniture, burned bright red. Rubber gave off a dull, deep shade of red, along with thick clouds of black smoke. Chemicals went up in a brilliant white flame with hardly any smoke. Whenever another load of incendiaries landed, the area suddenly came to life in a burst of brilliant blue-white.

Although the incendiaries and high explosives were still coming down, news from the coastal radar stations began to offer some hope. By about 4 a.m., the tall masts at Pevensey, Rye, and Ventnor had not detected any activity from Luftwaffe bases on the Continent for over an hour. Radar screens were showing that more enemy aircraft were returning to their bases than were taking off for London. As they lost altitude and began descending toward their home runways, the bombers disappeared from radar screens as if by magic.

At Fighter Command Headquarters in Stanmore, the WAAF plotters continued to push the red arrows across the huge table map, just as they had been doing all night. But as the hour approached 5 a.m., the arrows retreated steadily southward—across Kent and Sussex and Surrey toward the Continent. From the gallery above the map, Air Marshal Douglas and his staff watched the arrows being pushed southward until they were removed from the board, one by one.

The last bomb to fall landed on the northwest corner of Scotland Yard at 5:37 a.m. It destroyed the Metropolitan Police’s filing system—the records of over one million criminals were shredded into so much confetti. No one realized that the air raid had ended; the fires showed no signs of subsiding, and the sounds of thousands of fire pumps had been drowning out the noise of the bombers’ engines for the past several hours. When the planes were gone, no one noticed at first.

But members of the Observation Corps knew that the Luftwaffe had gone. From their stations many miles from London, they could hear the bombers as they flew back to their bases. The last enemy aircraft left the English coast at 5:50, as officially noted. In London, the all-clear sounded two minutes later. All over the city, the high-pitched howl of the sirens flooded the blacked-out streets and penetrated the interiors of air-raid shelters. From Hammersmith to East Ham, shelterers came out to see for themselves the fires they had been hearing about all night. They were appalled by what they encountered.

A total of 505 German bombers had attacked London during the seven-hour raid. According to official German records, 358 had bombed London during the first sortie and 147 during the second. German archives also record that 14 bombers were shot down, including the two Heinkels destroyed by P/O Humphrey. The first sortie dropped 498 tons of high explosives, the second sortie another 210 tons. According to the London Fire Brigade, about 2,200 fires were started. Nine were classified as conflagrations, 20 as major fires that required at least 30 fire pumps, and 30 as serious fires requiring up to 20 pumps.

The attack had done serious and long-term damage to Britain’s war industry. Factories producing materiel for the forces, including plants that manufactured munitions, parts for tanks, and equipment for the navy, had either been destroyed or were forced to shut down for many months. In the port of London, four docks and 24 wharves had been put out of action, which meant that the port could only operate at 25 percent capacity. All of London’s main rail stations had also been put out of action. Nearly 8,000 streets—one-third of the roads in greater London—were blocked or inaccessible. Millions of households were without gas, water, or electricity—155,000 households in one borough alone were without utilities—along with thousands of businesses and factories that had not been hit by German bombs. The most visible—as well as the most publicized—victims of the air raid were London’s old and historic buildings. St. Paul’s Cathedral was damaged, along with many centuries-old churches. The House of Commons had been completely burned out; there was nothing left of the chamber except a fire-blackened ruin. Over 1,400 people had been killed. Another 1,800 were seriously injured and would die in hospitals. Two thousand fires still burned out of control and would continue to burn for the next several days.

Throughout the day on Sunday, residents went out to assess the damage that had been done. A good many were saddened and distraught; others were angered at the sight of so much destruction, as well as at their inability to do anything about it. A father living in north London took his young son up on the roof of their building and pointed toward the smoke and fire. “I want you to see this, and I want you to remember it,” he said. “I want you to remember what the Germans did.”

But a woman living in a southern district of London had a completely different point of view. “Just heard the terrible news that Westminster Hall was hit last night, also the Abbey and the Houses of Parliament,” she wrote in her diary. “I cannot comment on such disasters. I just feel grievously limp. I feel we must have sinned grievously to have such sacrifices demanded of us … I can see our ancestors looking down at us reproachfully and saying, ‘We gave it to you. You have not guarded it and handed it on as you received it. You have failed, even those of you who loved it best.’”

But the most pressing worry on Sunday morning was that the Germans would be back again that night. About 700 acres of the city were still burning; these fires would create a target for the Luftwaffe’s bombers. If they returned, the result would be nothing short of a full-scale disaster. An administrator at London Regional Headquarters predicted, “If we get another like this tonight, we shall have to call the troops in.” An alderman from the district of Southwark told another official, “In my opinion, sir, two more nights of this and London will be at a standstill.”

“We can’t take much more of this,” a woman said. She had lost her flat and all of her possessions for the second time since September, and she spoke for a good many London residents. The air raid had caused widespread ruin throughout the city and killed 1,400 of its residents, but most damaging of all, it had done irreparable harm to morale. The bombing had all but broken the city’s spirit. “I began to really worry for the first time, and to realize to what deep depths of their being the May 10 raid had shocked and shaken the people of London,” an American reporter remarked. “It was just one raid too much.”

However, the bombers did not come back that night, or the night after that, or for the next several weeks. People began to wonder why the raids had stopped so abruptly. Hitler must have had a reason for the sudden peace and quiet, and it was bound to be a nasty reason. “Something’s up,” a police constable said. “Jerry’s planning something, and you can bet your life it’ll be bloody painful.”

Hitler certainly was planning something, but what he was planning had nothing to do with London. On June 22, 1941, German forces invaded the Soviet Union. From mid-June onward, Hitler would be devoting his full attention to waging war against Russia. By May 10, about two-thirds of the Luftwaffe had already been transferred to the east. The attack of May 10 had only been a parting shot, a decoy to keep everyone watching England while Germany prepared to attack Russia.

After May 10, the Luftwaffe would not send another large-scale raid against London; the main portion of its bombers and fighters had been sent to Russia. London’s Evening News told the story in a concise, five-word headline on June 23: “BLITZ OVER. MOSCOW’S TURN NOW.”

The residents of London could afford to breathe a sigh of relief.

Author David A. Johnson has written for WWII History on a variety of topics. He is also the author of numerous books on subjects ranging from the Civil War to World War II. He resides in Union, New Jersey.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments