By Richard Higgins

New Mexico and its capital of Santa Fe bring to mind some beautiful images. Stunning sunsets, unlimited vistas, a plethora of art galleries, the spectacular food enlivened with the local green chile, an ancient Native American culture that still thrives, and a Spanish heritage tradition going back to within 50 years of Columbus’s arrival all make for a unique cultural and physical environment. The Land of Enchantment, the City Different, tourist mecca––but spy capital?

Yes, spy capital. From the late 1930s until 1946, Santa Fe and its larger partner in New Mexico, Albuquerque, were the sites of some of the most famous and intense spy activity in world history. No one knew about it for years—except the foreign agents involved.

While this article deals primarily with the World War II era, there have also been other major espionage incidents in New Mexico since then. For example, perhaps the greatest defector in U.S. history, a dismissed CIA operative named Edward Lee Howard, escaped from Santa Fe in 1985 in a bold scheme to flee to the Soviet Union.

What goes on out in the middle of the American Southwest? What drew Soviet spies to the Land of Enchantment? Author E.B. Held, a retired CIA operative, claims in his highly recommended A Spy’s Guide to Santa Fe and Albuquerque, that Santa Fe is a “sacred city” for Russian operatives and that the Russian agents often have their picture taken in front of the iconic Cathedral Basilica of Francis of Assisi and its statue of Bishop Lamy made famous by Willa Cather.

To properly assess New Mexico’s leading role in espionage, we must go back in time and watch an extraordinary sequence of events that led to one of the greatest assassinations in history—and one of the most spectacular intelligence coups ever accomplished, both associated with Santa Fe.

Winston Churchill once famously said, “I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia. It is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” When we apply this to Soviet intelligence gathering, this is only the beginning of a journey compounded by deception, misdirection, and hidden truth—a wonderful field for historians to explore. The truth is out there, but hidden, and only trusted sources are to be relied on. But who to trust? There is the rub!

Soviet Intelligence in the USA

To establish a context for these events, we must first understand the Soviet intelligence presence in the United States in the late 1930s. Soviet spy agencies, represented by the GRU (Chief Intelligence Directorate, or military intelligence) and the NKGB (People’s Commissariat for State Security, or political and internal security bureau, including the GULAG, or political prison camp system), had over 20 agents operating in the U.S. at the time.

The former KGB originated as the Cheka and went through many name changes such as OGPU, GPU, NKVD, NKGB, and finally the well-recognized KGB, all culminating in today’s SVR (Foreign Intelligence Service) and FSB (Internal State Security Service). During the prewar period, NKGB was the most common name, so we will use that title whether it was true in a particular year or not. The acronym nicely combines our modern understanding with the past NKVD. The title GRU is still common, and while not always in use, is the most recognized identification for Soviet and current Russian military intelligence.

First Resident, Second Resident

Both of these intelligence agencies developed some unique innovations in spycraft to further the cause of communist world revolution. The first of these innovations was the concept of the “two residencies.” Simply put, the “first resident” was a member of the Soviet Embassy in any given country. He did not report to the ambassador but ran his own organization to gather intelligence, reporting to Moscow Center. These agents were immensely important figures in the GRU and later the NKGB, and much was expected of them, even though they were somewhat visible in the “light of day.”

The “second resident” would be a person in a country illegally and equipped with a false “legend” or life story, and would usually be engaged in some sort of business venture as a “front.” They were to have no contact with the first resident but would use a member of his team, usually a secretary, to communicate. This caused a number of problems and agent exposures, and in the late 1930s was corrected to “no contact” between the two. The second resident was to use his business cover to infiltrate industry and government to obtain needed intelligence, frequently giving up Communist Party membership to be in this role. While this was done to separate them from being associated with the Party, it also served as a kind of loyalty test. This two-pronged intelligence offensive would prove very successful over the years.

The second innovation to support the twin residencies, and arguably one of the most innovative inventions in espionage, was the use of “Mrachkovski Enterprises,” named after their inventor, S.V. Mrachkovski. Begun in the early 1920s but expanded after the failures of the Comintern, these were legitimate businesses opened around the world to provide agent cover, training, infiltration avenues into government and business, and a source of clean money. This proved so successful that many agents were never identified and a number became highly important assets during World War II.

The NKGB vs the GRU

Armed with these twin tools, both Viktor Suvorov (a false name for Vladimir Rezun, a post-World War II GRU defector from whom the West has learned much of the GRU operating technique) and Walter Krivitsky, the first GRU defector, asserted that by the 1930s the GRU was the most effective intelligence service in the world.

The lines of control between the two agencies were never clear and their internecine warfare was spurred on by Stalin. Both agencies were heavily purged in the 1930s and 1940s with executions of the GRU leadership almost commonplace. The NKGB experienced purges, too, but its leadership was as stable as a rock after 1938 because it was led by Stalin’s fellow Georgian henchman and chief executioner, Lavrenti Beria.

The GRU was and is the larger of the two agencies. Always shrouded in immense secrecy, at one time its officers could wear any Soviet rank and insignia they chose and, having no insignia designation, could not be identified as GRU; this truly was an army of ghosts. Their size dwarfed that of the NKGB operatives but, in the paranoid and personality-driven world of Joseph Stalin, they never attained his uncompromising support and paid a heavy price for this shortcoming.

The NKGB would become the senior espionage agency during World War II due to Stalin’s increased support of Beria. This was later confirmed by Beria’s assignment to the leadership of the Soviet atomic bomb project in 1944.

Operations in the United States

In this complex relationship, both agencies operated overseas residents through the Soviet embassy and consular offices and as noted above in private life. Their assignment was singular: steal all the technical and scientific advances possible from the United States. In the 1930s this consisted of tank design, ciphers, and the counterfeiting of millions of dollars of U.S. currency. Later the prize would be much larger.

As the United States entered World War II, the agencies’ assignment also became understanding American strategic and political thinking. There were hints of this activity occurring at the time in the United States and even some outright confessions by agents, but these were ignored by the FBI and American military intelligence. The price of this failure was immense.

Killing Trotsky

Prior to the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, the NKGB was primarily focused on internal purges and suppressing external communist “deviants.” At the top of this list—and Stalin’s primary focus—was the assassination of Leon Trotsky, Lenin’s great partner in the 1917 Russian revolution. Stalin had been successful in having Trotsky exiled and thus removing him from the succession battle in 1929. However, being Josef Stalin, he could not abide a major foe remaining alive. He ordered Beria and the NKGB to make Trotsky’s assassination at his exile residence in Mexico City their number one priority.

The man chosen to lead the overall plan would become a legend in spy circles: General Pavel Sudaplatov, a highly prolific NKGB assassin and eventual spymaster for the atomic spies. In 1994 he wrote his highly controversial and often misleading memoirs, Special Tasks, in which he recounted his many death-dealing enterprises, which included an assassination using a mined box of candy!

For all of the care needed in reading the memoirs, they provide a fascinating view into the Soviet hierarchy of the period. The operation, as with almost all Soviet “special tasks,” was compartmentalized and run through a number of groups. One of these groups was led by legendary NKGB agent Josef Grigulevich, a Lithuanian raised in Argentina. This agent was so resourceful that in his next assignment he became the Costa Rican ambassador to the Vatican!

However, his problem in 1940 was to have an absolutely secure “safe house” to use for planning Trotsky’s assassination and his subsequent escape. He chose Santa Fe, New Mexico, for his safe house. His father had been a leading owner of pharmacies in Argentina, and somehow Grigulevich managed to hook up with the Zooks––a Lithuanian family running a drugstore on Santa Fe’s central plaza.

The Zooks were likely never aware of Grigulevich’s activities, and his welcome may have come from the Zooks’ daughter, Katie, who ran the pharmacy. Katie was a bit older than the handsome, worldly agent, and perhaps a relationship developed. However it happened, this unlikely relationship and the safe house in this unlikely location were perfect for his plans. The building still stands today as a Häagen Dazs ice cream store, and it is clear why it was a perfect choice. A much obscured back entrance allowed access with little chance of being seen––not that any U.S. agency was looking back in 1940.

On May 24, 1940, Grigulevich and his team of 20 agents, primarily Spanish Civil War communist veterans, were led into Trotsky’s Mexico City compound by a naïve American bodyguard they had duped. Armed primarily with pistols and one rapid-fire weapon, they proceeded to blast Trotsky’s bedroom to no avail; the Trotsky household survived.

Safe House in Santa Fe

Grigulevich was livid over his team’s failure and shot the American so he could not identify the agents. He and the men then split up, and Grigulevich returned to Santa Fe where he laid low before heading back to Argentina and his eventual placement at the Vatican where he would receive orders to kill the Yugoslav partisan leader Tito; these orders were never carried out.

Upon briefing Stalin of the initial failure to kill Trotsky, General Sudaplatov commented, “[Stalin] appeared to be patient and prepared to play for higher stakes, putting his whole agent network on the line in a final effort to rid himself of Trotsky.” Trotsky was successfully assassinated by another team supporting lone agent Ramon Mercador, who accomplished the task on August 20, 1940.

Sudaplatov discussed the disposition of the safe house in Santa Fe in his memoirs. He was wrong in stating that Grigulevich owned the drugstore and passed it on to another agent; it stayed with the Zooks until the 1990s. He was perhaps spreading disinformation when he stated that the house was used to spy on the Manhattan Project in nearby Los Alamos, but an element of truth is likely in his statement that some of the agents involved in the Trotsky plot also assisted in the espionage associated with the atomic bomb project.

The Minds Behind the Manhattan Project

In 1939, a number of scientists influenced Albert Einstein, the most famous scientist and refugee from Nazi persecution, to write a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt pointing out the possibility “that extremely powerful bombs of a new type might be developed.” The meeting that followed the delivery of the letter between prominent physicist Alexander Sachs and the president and his staff caused Roosevelt to launch the most secret and destructive project seen up to that time in human history.

Secret atomic projects were already underway in Britain, Germany, and Japan, so the U.S. was a bit late getting into the game and, in fact, made a very slow start, especially when compared to Britain. Initially just a committee to research the issue under a former Massachusetts Institute of Technology dean, Vannevar Bush, this innocuous start would grow into the Manhattan Project.

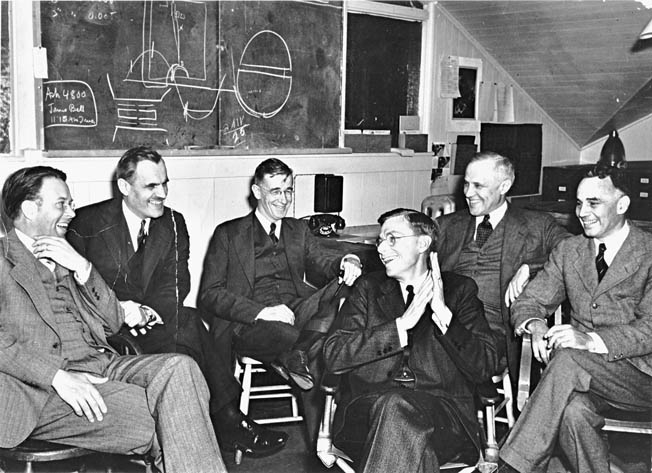

With Italian physicist Enrico Fermi’s first construction of an atomic pile that sustained a controlled chain reaction under the stands of the football stadium at the University of Chicago in late 1942, things began to move with increased urgency. By July 1942, Robert J. Oppenheimer, a brilliant, complex, and driven physicist from the University of California at Berkeley, was leading a group of scientists trying to prove if a bomb was possible. He successfully handled the many egos in the room and caught the attention of the Army’s chief for atomic issues, Brig. Gen. Leslie Groves of the Corps of Engineers. Groves was a stern, no-nonsense military man, but this strange partnership would yield amazing results in only three years. In May 1942, Groves selected Oppenheimer as the scientific head of the project.

A small group consisting of many of the world’s leading physicists (which would later grow to include 12 Nobel Prize laureates including Fermi, Niels Bohr, Edward Teller, and Ernest Lawrence) would be on the team. Tens of thousands of other scientists, engineers, and technicians were recruited for the project, as well as the required support staff of cooks, medical personnel, drivers, security, and so on.

Choosing the Locations For the Manhattan Project

The project would be based in three states. Oak Ridge, Tennessee, was chosen first as the major material production site; Hanford, Washington, would later be chosen for plutonium production, but the main core of the project—the scientific and development site—was not yet chosen. At this early stage of the project, a momentous decision was made that would change New Mexico forever.

The site selection was immensely influenced by Oppenheimer. There were specific criteria revolving around security, water supply, and access that were used to evaluate other southwestern states. They were eliminated, and only sites in New Mexico remained. There was no shortage of remote sites to choose from, and in November 1942, Groves and Oppie, as Oppenheimer was known, toured them to make the final selection.

Oppenheimer loved and was very familiar with New Mexico. His family had a small “ranch” up the incredibly beautiful Pecos River Valley named “Perro Caliente” (translation: “Hot Dog”). He had ridden and hiked the area extensively, most famously naming Lake Katherine for a friend. One of the places considered was the site of Los Alamos Ranch School––a very upper-crust boys’ school that the likes of author Gore Vidal, Arthur Wood (later president of Sears), and Roy Chapin (later president of American Motors) had attended. The school was extremely rustic and would provide the beginning of a physical plant that grew many times over. But Oppie loved the site and Groves loved the security potential of this “middle-of-nowhere” location.

But were there other reasons behind the choice? When Groves offered Oppenheimer the the opportunity to direct the project in May 1942, he likely did not elaborate on the fight he had had with the review committee over Oppenheimer’s leftist political views. The committee had initially resisted giving Oppenheimer the job but, in the absence of other viable candidates, eventually gave in to Groves.

Was Oppenheimer Influenced by Soviet Intelligence?

The issue that would plague Oppenheimer in the future and would eventually end his career was his association with communism and known communists. In the late 1930s and through 1941—indeed until he got the job with the team in 1942—Oppenheimer associated regularly with known Party members and donated to the Communist Party. Additionally, his recent wife, Kitty, and his brother Frank and sister-in-law Jacqueline were all card-carrying Communist Party members into the early 1940s. They remained members after the notorious Hitler-Stalin Pact, which saw the ranks of the party diminished by this realpolitik assault on some sincere humanists. The Oppenheimers’ association with organized communism is all a matter of record and accepted by the great majority of historians of the period. After this, the matter of Oppie and communism gets very murky and has never been fully explained. However, it is known that there were several incidents during the war involving Oppie’s communist acquaintances that would come back to haunt and eventually bring him down in the mid-1950s.

Oppie loved New Mexico, and it met the criteria for the site at the remote Los Alamos location, but was there something else behind that decision in November, 1942? The question is whether Oppie was listening to another source arguing for the site 20 miles from the former NKGB Santa Fe location. Did one of his family party members push for the location at the urging of GRU or NKGB agents? Unfortunately this will remain speculation unless a new source appears or some hidden government document or an unimpeachable Russian source surfaces.

The remoteness of the location was intended to prevent access to the scientists and isolate espionage agents, but was this already undone? We may never know, but history records that one of the major espionage coups in all human history was about to unfold in sleepy New Mexico.

“Those Atomic People!”

By the spring of 1943, the Manhattan Project was well underway. Thousands more personnel were arriving, and over 100 buildings were built housing the first scientific personnel. The general living and working conditions at the site ranged from rustic to primitive; this would improve but would remain a constant challenge. Santa Fe was drawn into the project when its public face was set up at 109 East Palace near the Plaza. Here all new arrivals would check in, and tabs would be kept on those visiting the town. La Fonda Hotel also played a part as the Oppenheimers’ first home in the area and was used for meetings and other functions. Both sites are still there today.

One aspect of the project that was given great attention early was the requirement for very tight security, at the insistence of General Groves. Initially, he had wanted to commission all scientists into the military for the extra control this would allow, but the idea was discarded. The project was not only highly secret, but the scientists were working on compartmentalized problems and discouraged from sharing between the different groups. This would be somewhat relaxed in later stages as the importance of cooperation became apparent.

The security would remain tight with fences, frequent screenings, letter reading and censorship by authorities, and phone taps. There were lapses, however, which seemed to indicate everything was not under control. While told not to associate with locals, some personnel snuck off to meet wives who were not allowed on base. The manager of the lodge at nearby Bandelier National Monument, which was used for recreation and housing by the project, called them “those atomic people!”

Finally, there was a hole in the fence surrounding the compound that never seemed to stay repaired. It was used to access to the beautiful New Mexico wilderness by project personnel and by the local Pueblo people to sneak on to the base to shop at the PX!

Klaus Fuchs

Yet, hardly any of this mattered because from its early days the Allied bomb project was being reported on by a British GRU agent. The secrets would leak at a faster rate when perhaps the most important of the atomic spies, Klaus Fuchs, codename “Charles,” arrived in New Mexico with other British scientists in 1944.

Fuchs was a German communist who fled Germany in 1933 after Hitler’s rise to the chancellorship. While in Britain he studied physics. His mother was driven to suicide by the Nazis, which further enflamed his anti-Nazi passion, which was even further fanned by the 1941 German invasion of the Soviet Union. Just before this invasion, Fuchs was taken on at the British bomb project and later in the year secretly recruited by the GRU. He contributed valuable information to his contacts, which author E.B. Held said was used by Beria to impress Stalin with the necessity of instituting a Soviet atomic project.

Fuchs’ arrival at Los Alamos would be the breakthrough that Soviet intelligence services had been pushing for but, up to that point, had been generally unsuccessful in accomplishing. The contact with Moscow Center for Fuchs and other Soviet agents would be the Soviet Consulate in New York City, which was the American headquarters for the NKGB. While the FBI was on to the New York location, none of the “rest of the story” was known until the late 1940s.

Before arriving at Los Alamos, Fuchs passed on valuable intelligence regarding the work being done at Oak Ridge to his GRU contacts. This was after working for several months on the Manhattan Project in New York City at Columbia University.

His arrival at Los Alamos in the summer of 1944 began a series of espionage coups that are still legend in Russia. Fuchs made sure he not only dealt with his specialty, theoretical physics, but volunteered to be project historian. He also attended, ironically, the sessions that Oppenheimer convinced Groves were needed, where the free exchange of ideas was allowed. The Soviet presence was at the very heart of the project!

Codename Arno

Fuchs’s main contact initially in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and later in Santa Fe, was Harry Gold, codename “Arno,” a naturalized American born in Russia and an NKGB agent. This was because the NKGB had taken over the GRU network due to Kremlin politics and would be the lead agency for the campaign to infiltrate the Manhattan Project, codename “Enormoz.” Fuchs was likely unaware of this change in “ownership” and would proceed to gather data for the next meeting, scheduled for June 1945, in Santa Fe.

Harry Gold traveled to Santa Fe in the company of his elderly mother to throw off suspicion. E.B. Held tells us that both men synchronized their watches to the Spitz Clock on the plaza. (Today the clock is not in its original site, but at the northwest corner of the Plaza). At precisely 4:00 pm on June 2, they met at the bridge on the Paseo de Peralta and East Alameda Street. The bridge has since been replaced and the original location was slightly east.

After discussing some issues, Fuchs drove Gold to the bus station for the return to Albuquerque and in the vehicle handed him a packet of information that would change the world. The packet’s information would arrive at Moscow Center in approximately 10 days. The details are still astonishing. Contained in the packet were sketches of the bomb, technical discussions of the two different triggers to be used for “Little Boy” and “Fat Man” (nicknames for the bombs; they were uranium and plutonium bombs, respectively), details of the upcoming atomic test, and finally the U.S. intention to use the bomb against Japan based on successful test results—a complete view of the project!

On July 16, 1945, the world’s first atomic device—the equivalent of 20 kilotons of TNT—was detonated above the sands at a remote desert test site codenamed “Trinity,” some 35 miles southwest of Socorro, New Mexico. On August 6, a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber named Enola Gay and piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets flew over Hiroshima, Japan, and dropped the uranium bomb that destroyed the city in a flash and killed 90,000-166,000 persons. Three days later, when the Japanese government did not immediately agree to surrender, a second B-29 (named Bock’s Car, piloted by Major Charles Sweeney) dropped another atomic bomb, the plutonium weapon that exploded over Nagasaki, killing 60-80,000 people. On August 15, the Japanese government agreed to surrender unconditionally. World War II, a war that had claimed some 50 million lives, was at last over.

Fuchs and Gold would meet once more in Santa Fe—in September 1945 at the corner of Paseo de Peralta and Bishops Lodge Road near the Masonic Rite Temple. During their drive, Fuchs briefed Gold on the results of both the Trinity test and the results from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It can safely be said that the Soviets knew as much about the project as any reasonably well-placed scientist working on the project. The results of these amazing thefts would advance the Soviet atomic-bomb effort by years.

The father of the Soviet bomb, Igor Kurchatov, stated in 1943 in his report to the Kremlin, as quoted in Jeffrey Richardson’s A Century of Spies, “The material is of tremendous, inestimable importance for our State and our science.” This was information generally provided by Fuchs and others associated with the British project. However, several American agents for the Soviets were soon to come on line with even more devastating effect and, when they were caught, it would precipitate one of the country’s greatest scandals.

Ted Hall

Unknown to Fuchs, there were other NKGB agents on site at Los Alamos, and they were American citizens. A brilliant, 18-year-old Harvard physics graduate with leftist ideals was brought into the project in 1944. He was Ted Hall, codename “Mllad,” meaning “young.”)

He would volunteer to spy for the NKGB, establishing contact in New York. It appears he was motivated by the appearance of a “worker’s paradise” in the Soviet Union. However, as a walk-in, he was under intense scrutiny by Moscow Center. It was arranged that his best friend, Saville Sax, codename “Star,” would be his courier before he met a real NKGB operative.

At their meeting somewhere in the vicinity of Central and First Avenues in downtown Albuquerque, Hall gave Sax an incredible written document detailing extremely critical information for the functioning of the bomb and, additionally, a list of scientists working on the project. Through the New York office this information was sent to Moscow Center.

Hall would make one more report to the NKGB via operative Lona Cohen (“Leslie”) in August 1945 and report on the results of the Trinity test; they met on the campus of the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. The incredible revelations provided by Hall advanced Soviet knowledge even beyond the Fuchs information.

Antenna, Liberal, and Bumblebee

Other NKGB agents were also operating, particularly those associated with Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Julius Rosenberg was codenamed “Antenna” and later “Liberal.” He had quit the Communist Party in 1943 to become a NKGB agent and immediately began to prove his value to Moscow Center. He ran a number of NKGB placements, which succeeded in enlarging the penetration of the project to fill out the technical detail. Among these agents was a young American serviceman stationed at Los Alamos, David Greenglass (“Bumblebee”), who was Rosenberg’s brother-in-law.

Greenglass worked on the plutonium bomb, and his input on the engineering side versus physics theory was instrumental in supporting detailed reports from Fuchs and Hall to Moscow Center. This relationship would prove fateful for the Rosenbergs. Greenglass met with Gold twice at his rooming house in Albuquerque. The address is 209 High Street and it is currently the Spy House Bed & Breakfast. Greenglass’s information regarding the implosion method of the device supported statements from both Fuchs and Hall. This was critical to the Soviets, who were extremely concerned about U.S. misinformation or agents’ personal agendas.

Greenglass’s confirmation of both the Fuchs and Hall data assured Moscow Center that they were receiving good if not invaluable information. However, this fateful meeting between Gold and Greenglass, against Gold’s intuitive concern for spycraft risks, set in motion a series of events with fatal consequences.

These amazing espionage coups proved to be the height of the NKGB’s penetration of the United States in the 1940s and accomplished in the face of what author Held observed as, “This was wartime New Mexico, which, in 1945, probably had the highest per-capita presence of counter-intelligence officers of anywhere in the United States.”

Uncovering Soviet Espionage in America

The bright red star in the West began to fade as the light struck U.S. analysts regarding Soviet espionage. Soviet efforts had begun to be exposed as early as 1939, but U.S. agencies were not yet listening. In the Soviet Union the purges were directed at first the NKGB, then the GRU, and finally the military command structure in the late 1930s. As the purges developed in the Soviet Union, the first GRU defectors emerged. Ignace Poretsky was assassinated after fleeing to Switzerland in 1937. His wife Elizabeth’s book Our Own People is well worth reading for a firsthand account of the period. Then, even more sensationally, the GRU defector and colleague of Poretsky, Walter Krivitsky, was judged to have committed suicide while in Washington, D.C., in 1941 after defecting in 1937. His book In Stalin’s Secret Service is also an excellent primer on life under Stalin and the Soviet intelligence service.

These events made numerous Soviet agents very nervous. The most nervous and influential was Whittaker Chambers, an American citizen who approached the U.S. government with his revelations of Soviet spying in 1939. Chambers was a GRU agent with ties throughout Washington, D.C., and the United States. He also managed one of the GRU’s most important agents, Alger Hiss. Chambers and other defectors were instrumental in deeply hurting Soviet spying in the U.S. In the months following Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, GRU chief Golikov came to America to meet with the Roosevelt administration and Roosevelt himself on war aims. However, an important part of his mission was to reestablish the GRU network in the U.S. Due to Depression-era leftist sympathies within the Roosevelt administration and the “anti-fascist” alliance with Moscow, this was not difficult to accomplish.

The FBI’s Investigations

In 1943, FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover received an anonymous letter detailing Soviet spying in America. Sudaplatov stated in his memoirs that the letter was sent by the NKGB resident in the Washington, D.C., embassy of the Soviet Union, Lt. Col. Mironov. In this famous letter, declassified in 1996, it described agents in all U.S. industrial towns and that they were stealing the “whole of the war industry.” Additionally, the letter contained the first discussion of the Soviet massacre of Polish officers in the Katyn forest. Many historians believe that this bombshell was really the beginning of the Cold War.

The letter stunned the FBI, but initially there was little follow up. However, this likely provided a boost for the new U.S. Venona project for decryption of secret Soviet radio traffic, which began in 1943. The Venona project would later be responsible for establishing U.S. insight into the Soviets’ wartime agents and efforts. (See WWII Quarterly, Spring 2011.)

Then, Elizabeth Bentley, a NKGB agent inside the United States, codename “Good Girl,” surrendered in 1945 and was debriefed by the FBI. Her revelations startled the agency, and gradually comprehension of the massive Soviet infiltration began to come to light. Surprisingly, this massive breach of security would only be rapidly exposed by another famous GRU defection in 1945, that of the Soviet Embassy GRU officer in Canada, Igor Gouzhenko. Gouzhenko would defect, in his words, for, “The greatest gain is the one I feel deep down inside: that I did my duty towards the millions enslaved and voiceless in Russia today.”

His defection and discussions with Canadian, British, and U.S. intelligence brought to light major portions of the Soviet atomic spy network. This was because the GRU was in charge of Canadian atomic espionage. Gouzhenko’s information would have a profound effect on relations between the Soviets and the West and the degree of security maintained in the West against Soviet efforts. Most importantly, he would confirm the Venona transcripts and provide the true names for the codenames of American citizens working for the Soviets. Additionally, in 1945, the FBI would seek out and interview Whittaker Chambers again, with much greater interest. However, his bombshells would be reserved for 1948.

Alger Hiss One of the Soviet’s Most Valuable Agents

Alger Hiss was Whittaker Chambers’s most important agent in the 1930s, and Hiss had continued to grow in his government career during the war years. This was perhaps the most significant result of the lax attention to Chambers’s revelations in 1939 by US counterintelligence forces. The low priority or lack of belief in Chambers’s information would persist until the Gouzhenko revelations and those of Elizabeth Bentley.

However, there were already concerns over Hiss’s possible Soviet connection in the war years. Surprisingly, that did not prevent him from accompanying Roosevelt to Yalta as a special State Department team member. Possibly his greatest contribution beyond Yalta was the providing of plain-language copies of U.S. documents which assisted GRU deciphering teams working on U.S. codes during the war. At Yalta, he was not intimate with Roosevelt but, as a note-taker, was able to attend numerous discussions of U.S. policy and Stalin’s demands.

Meeting daily with General Milshtein of the GRU, Hiss briefed the Soviets on the U.S. response to Soviet proposals regarding the key questions concerning postwar Europe, Soviet participation in the war against Japan, and the future of Poland. This valuable information was presented daily to Stalin and, along with the atomic information, provided the Soviets with a complete picture of the post-World War II world.

The implications of the exposure of America’s atomic secrets and post-war plans were truly decisive and strategic—not only promoting the development and distribution of atomic weapons but the laying in place of another conflict post-World War II. Stalin knew that the establishment of his plan for Eastern Europe had to be finalized by the Big Three before the first use of the atomic bomb that would radically change his negotiating position. Based on this espionage, it is clear that Stalin knew much more about the U.S. bomb efforts than President Harry S. Truman did when he announced it at Potsdam.

Venona Project Controversies

The Hiss story would not end with his arrest and conviction in the late 1940s and early 1950s but continues this day. As a historical side note, Hiss and other American officials flew to Moscow for meetings after Yalta, and while there Hiss was secretly decorated with the Soviet Order of the Red Star for his services to the Soviet Union! The evidence against him has been confirmed by both Russian and Venona sources as well as Soviet defectors.

The defectors’ revelations would eventually link up with Venona decryptions of Soviet radio traffic. The information provided by the defectors needed to be corroborated, and this was the best method available to U.S. counterintelligence. However, the information was highly classified and could not be made public, which limited its use in court cases. Hence the need for confessions by any suspected agents.

There is still controversy surrounding whether or not President Truman ever knew of the effort to cripple Soviet espionage in the United States. In 1949, working on Soviet radio traffic from 1943-1945, the project hit pay dirt. A number of decrypts revealed the spying on the Manhattan Project. Through some poor Soviet message discipline, the codenames of the four major spies, three of whom had confessed, and their identities were established. Venona would not be seen by the American public until 1995. All code names used in this article are from the Venona files.

The most damning exposure occurred in 1949 when FBI and British intelligence, through the use of Venona decrypts, identified Klaus Fuchs as a Soviet agent. When Fuchs was questioned, he immediately began to talk, and the story of the atomic spies began to surface. He implicated his contact, Harry Gold, who in turn implicated his contacts, the Greenglasses. When confronted, the Greenglasses named the Rosenbergs. All of these confessions were made as a trade for exemption from the death penalty. However, the Rosenbergs would never confess and would be the only atomic spies to pay with their lives. Ted Hall was suspected and questioned but successfully evaded punishment because the government could not reveal the real supporting evidence behind these allegations, Venona.

Oppenheimer’s Name Cleared

Numerous questions still remain about the Soviet infiltration of Enormoz. There are still questions and rumors about spies not caught. One persistent but unconfirmed speculation concerned an agent at Los Alamos, codename “Perseus.” Did he really exist? If so, who was he and how damaging was his role in the great victory of the NKGB? However, the most controversial questions by far concern codename “Chester.” Through a great amount of work using Venona decrypts and other sources, it was established that “Chester” was Robert Oppenheimer.

Further controversy was stirred up in 1992 when General Sudaplatov in his memoirs claimed that Oppenheimer was a Soviet agent. This was supported by other authors (notably Romerstein and Briendel in The Venona Secrets). There is little question that Oppenheimer was his own worst enemy. His very attitude toward authority and security made him a target. His opposition to the hydrogen bomb seemed to call into question his desire to keep the U.S. lead in nuclear weapons. His association with known communists, and indeed his own family members’ membership in the Communist Party, spoke volumes for his political leanings. His clumsy cover-up for some incidents during the war would surface to damage him badly at his Atomic Energy Commission hearing for renewing his security clearance. His abysmal performance at the hearing was almost a guarantee of defeat. He would lose that fight and become persona non grata with the government for almost a decade.

However, in 1962, President John F. Kennedy would ask his CIA chief of counter-intelligence to get to the bottom of the story. Amazingly, using Venona decrypts, the officer ascertained that there had been many attempts by the NKGB to turn Oppenheimer, but there was no confirmation in the decrypts that this ever happened. The CIA investigator concluded, as stated in E.B. Held’s A Spy’s Guide to Santa Fe and Albuquerque, “There was room for an honest difference of opinion.” This allowed Kennedy to hold out a hand to Oppenheimer and plan to award him the Enrico Fermi Medal for Distinguished Scientific Contributions to the United States. Unfortunately, Kennedy would be assassinated before presenting the medal; it was presented by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the White House in 1963. The current consensus of historians is that Oppenheimer was not a Soviet agent.

Legacy of the Manhattan Project

The United States and Soviet Union would wage a Cold War for 40-plus years—years which saw spycraft and combat between the two nations and their surrogates. The world would live under the shadow of nuclear destruction for all those years and in 1962 would almost see it become a reality during the Cuban Missile Crisis. However, it can be argued that greater wars were not fought because of the threat of these weapons.

The first of the events impacted by the Manhattan Project was the almost immediate end of the Pacific War following the use of the bombs. While hundreds of thousands of Japanese lost their lives in the atomic attacks, further millions of Japanese military and civilians, Chinese civilians, and U.S. military were spared by a quick end to hostilities. Estimates of Japanese and American casualties in the planned invasion of Japan are all well above the bomb casualties.

Add to this the anticipated further Japanese deaths from starvation due to the ever-tightening U.S. Navy submarine cordon as the war would have continued, and the numbers far eclipse the bomb casualty estimates. And what if the Soviets had invaded Japan? What if one includes continued Chinese casualties as the war went on? Poignantly, the 500,000 Purple Hearts minted for the American invasion casualties were never awarded but are still being handed out. Clearly the bomb decision was justified from the American viewpoint 65 years later. Additionally, in the years that followed, Europe was not invaded by the Soviets. The line was held in Korea. Berlin never fell to Soviet control.

A legacy of scientific advancement stems from the Manhattan Project in the sleepy tranquility of New Mexico. The state was no longer a somewhat backward locale. Instead, it became a major center of the nation’s science.

The chiles are still green and the sunsets stunningly beautiful, but a new blinding light that the world hopes never to see again was added in that high desert.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments