By Michael D. Hull

A generally overlooked factor of World War II has been the influence, sometimes highly significant, of nations that remained neutral.

Among them were Spain, Sweden, Ireland, and Switzerland. Another was Portugal, a proud yet peaceful buffer amid dictatorships and tyrannical regimes and a lifeline and haven for thousands of desperate refugees from all over Nazi-occupied Europe. Its historic capital, Lisbon, was the chief distribution port for International Red Cross Committee relief supplies to prisoner of war and internment camps, the main link for civilian flights between Great Britain and the United States, and a hotbed of espionage.

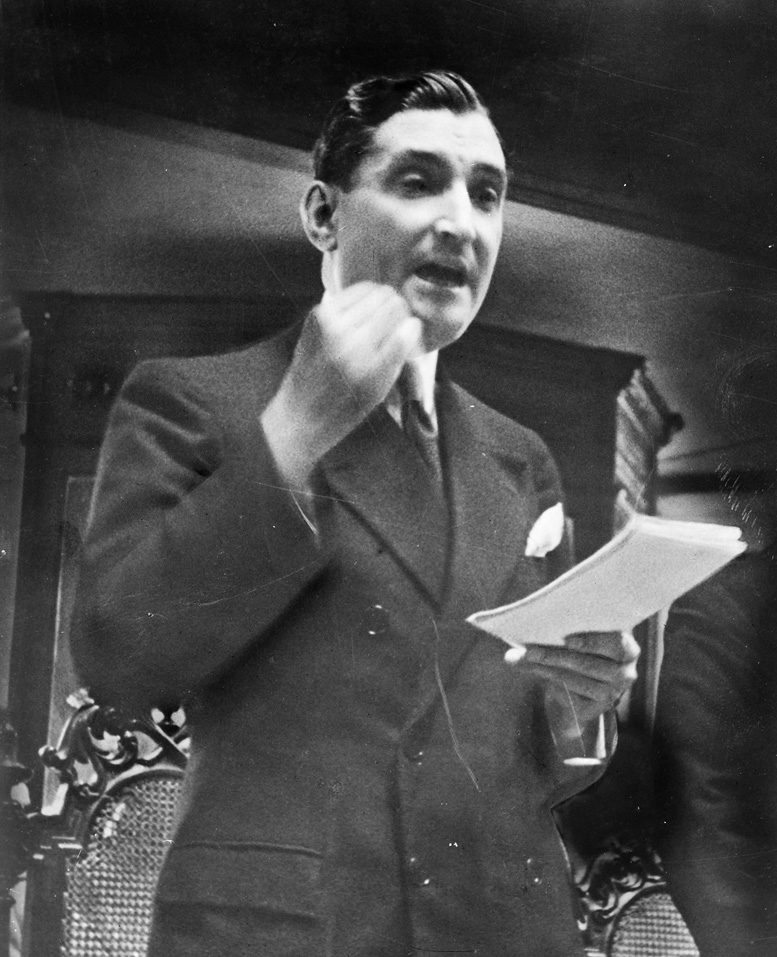

Portugal’s prime minister, Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, walked a perilous diplomatic tightrope as he guided unharmed his tiny nation and its far-flung colonies for the duration of the 1939-1945 global conflict. Although he harbored sympathies for the Allied cause and was threatened with a German invasion of the Iberian Peninsula, and although Nazi planners dreamed of placing U-boat bases along Portugal’s long Atlantic coast, the ascetic, reclusive premier managed deftly to maintain strict neutrality and keep his people out of the war.

Nevertheless, one of Portugal’s possessions—a nine-island, 910-square-mile archipelago in the mid-Atlantic—was a strategically vital and hotly contested area in World War II. No shots were fired there in anger, yet the Azores Islands came to play an important role in helping the Allies defeat the Axis powers and restore peace. Each global power—Britain, the United States, and Germany—plotted and schemed to gain use of the Azores, 800 miles west of the Portuguese coast.

The three powers each wanted the Azores and had their own ideas on how to achieve their aim. Each side suspected the other’s plans, and each had the same goal in mind—to occupy the neutral islands by diplomacy, intimidation, or armed invasion.

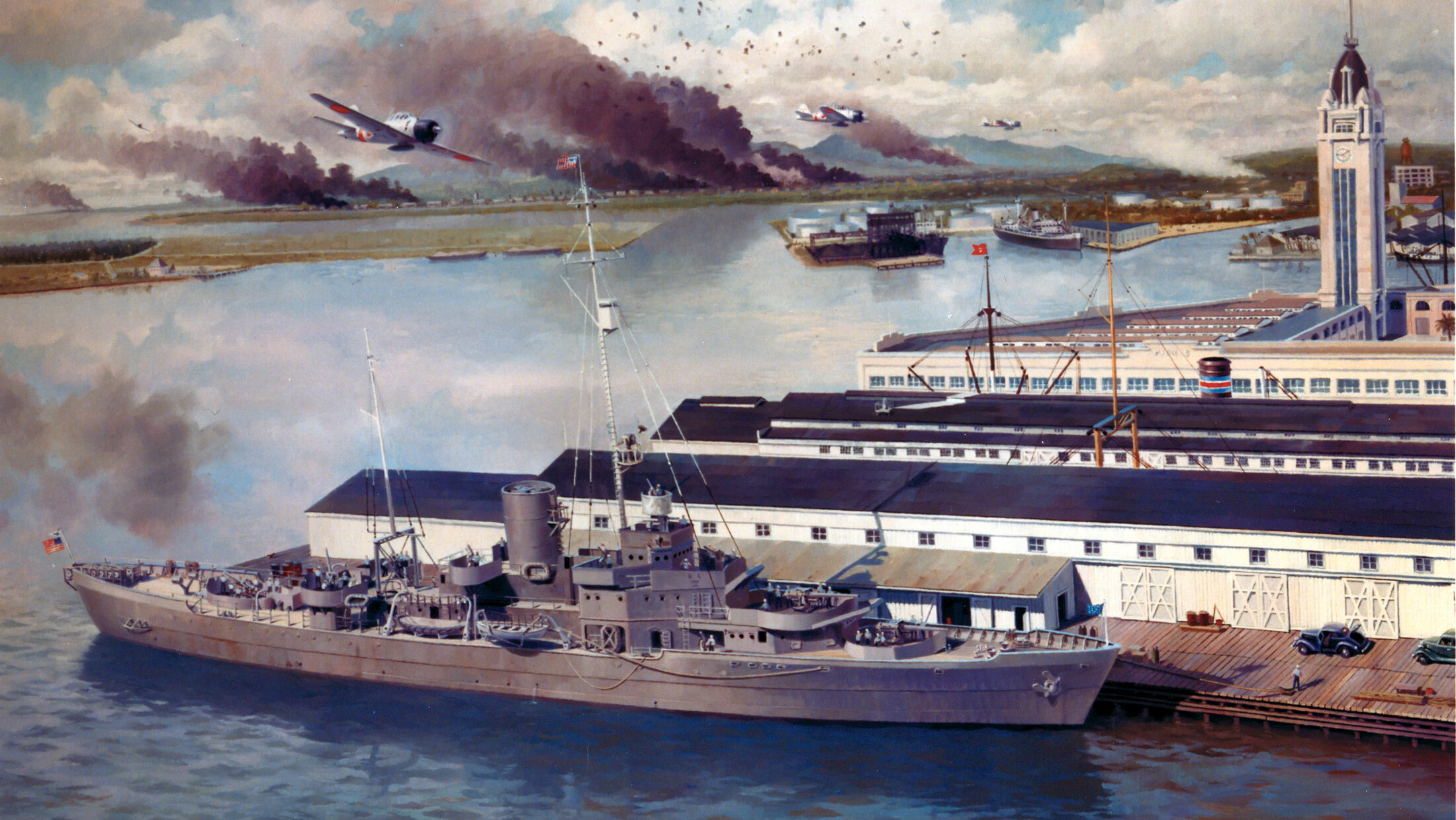

The Germans sought the Azores to give their navy a commanding position in the Atlantic and a simpler way to defeat Britain than by an English Channel crossing. But the German high command was too preoccupied with other objectives, and Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler tended to pay scant attention to maritime affairs.

American President Franklin D. Roosevelt favored immediate action against the scenic, peaceful Portuguese islands, and General William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, his vigorous, outspoken chief of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), planned a private, covert intrusion there. He suggested that the islanders be encouraged to rise up “spontaneously” in a concerted revolt against Portuguese authority. But the OSS plan was based on wishful thinking and ignorance, for the Azoreans were loyal Portuguese citizens and had never shown any evidence that they wanted independence. They always insisted, “Sou Portugues das Ilhas” (“I’m Portuguese first, then from the islands”).

Far off the mark in its premises, the OSS assumed that Salazar was “a dangerous fascist, a good friend of [Italian dictator Benito] Mussolini, and in league with the enemy,” and that the Portuguese leader would welcome a German occupation of the Azores. The harebrained OSS idea was mercifully squelched by able American diplomat George F. Kennan and the British ambassador to Portugal.

Early in the war, the British established air bases in Labrador, Greenland, and Iceland to furnish protection for convoys in the North Atlantic, where German U-boats preyed. But farther south, air cover was far out of reach for the central and southern ocean routes. With the liberation of continental Europe as the ultimate Allied objective, the entire Atlantic had to be made safe for the convoys carrying men and matériel to England. Failure to gain use of the Portuguese islands left a giant “black hole” in the Azores gap—a perilous gauntlet for the convoys to run.

For Hitler’s Germany, the Azores represented an ideal base for both U-boat operations and airfields needed for his “Projekt Amerika,” an ambitious bomb and rocket campaign against the U.S. East Coast. Reichsmarshal Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe, had authorized work on an intercontinental Messerschmitt “Amerika-bomber” that would carry a 3,000-pound bombload to New York. But the outbreak of war interrupted development. The concept failed to materialize, and the Luftwaffe lacked operational long-range, strategic bombers for the duration of the 1939-1945 war.

Britain and America, meanwhile, sought to use the Portuguese archipelago for air bases to shield the convoy lifelines in the central Atlantic, where Nazi submarine packs prowled freely and sank thousands of tons of vital shipping from 1941 to mid-1943.

This was the second time since the fall of France and the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940 that the fate of Western civilization hung by a thread. German submarines were sinking three Allied merchant ships for every one built.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who feared the U-boat menace above everything else, wanted an air base in the archipelago before the Germans got there first. If that happened, the Battle of the Atlantic could be lost. But Churchill realized that all diplomatic channels would have to be explored before there was any consideration of an armed entry into neutral territory. This was not the British way of doing things, and such an incursion would cause great embarrassment to the Allies.

Yet, gaining entry to the sprawling group of islands—Flores, Corvo, Terceira, Sao Jorge, Pico, Faial, Graciosa, Sao Miguel, and Santa Maria—was to prove a formidable diplomatic undertaking for the Allies. Vulnerable Portugal, whose troops had fought alongside the British on the Western Front in World War I, had no desire to become embroiled in another —and much wider—conflict. As one Lisbon official commented, “When an elephant sneezes, a mouse dies of pneumonia.”

To stay out the war, Prime Minister Salazar wanted neither side to use any of his territory as a base for offensive operations. His regime was a right-wing dictatorship, but Salazar, the mildest of European dictators, detested the Nazis and also feared communism. While many in the Portuguese upper classes admired Hitler’s new Germany and were influenced by it, the working people were sympathetic to the Allied cause.

In March 1939, Portugal and Spain, once bitter enemies, signed the Pacto Iberico, a treaty of friendship and nonaggression, and Salazar made an important early move that would benefit the Allies. He influenced the Spanish leader, Generalissimo Francisco Franco, to resist Hitler’s blandishments to join the Axis camp. When World War II broke out on September 1, 1939, with the German invasion of Poland, Spain and Portugal both declared their neutrality. Salazar’s foreign policy comprised two main elements: Iberian solidarity and the 1373 Treaty of Windsor signed by England and Portugal, the world’s longest standing alliance. The two countries had close economic ties.

The Portuguese admired Britain most of all the European nations, and while Salazar’s attitude toward Hitler and the Third Reich was reserved, his sympathy for Churchill and his people was friendly and unwavering. When Britain and France were forced to declare war on September 3, 1939, Salazar predicted that Britain would stand undefeated.

To be ready for any eventuality, Premier Salazar doubled the size of the Portuguese Army in 1940-1941 from 40,000 to 80,000 men. Because of the perceived threat to the Azores, 40,000 troops were stationed there, and this proved to be a diplomatic triumph for the shrewd Salazar. The Allies were sure that this had been done to defend against a possible German assault, while the enemy viewed the garrison’s aim as resisting a British or American landing.

Meanwhile, the strategic importance of the Azores was studied in 1941 by both Hitler and President Roosevelt, who had been making a number of moves to support the British while his own country was still neutral. Hitler gave instructions to prepare for Operation Felix, the occupation of the Azores and also the Spanish Canary Islands and Portugal’s Cape Verde Islands, both west of the African coast, to prevent possible Allied landings. Roosevelt promised Churchill that he would dispatch an occupying force to the Azores, as in the case of Iceland, if Britain could arrange an invitation from Portugal. Both leaders feared a Nazi thrust through the Iberian Peninsula and the seizure of Gibraltar, the British bastion guarding entry to the Mediterranean Sea.

In May 1941, the American president pressed for action to take over the Azores and the Cape Verde Islands to forestall what he imagined might be a German move into Spain and Portugal “at any moment.” FDR wanted a landing force of 50,000 men ready within a month. But when his advisers reported that a sufficient number of ships could not be found in such a short time, FDR “let himself be argued out of the thing,” according to Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau. Nothing came of it. There was no German threat to Gibraltar and no need, at that time, for an invitation from Lisbon.

But the Allied leaders and planners continued to study the strategic importance of the Azores and how they might gain a foothold there. While on their way to the Trident Conference in Washington in May 1943, the British chiefs of staff—General Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff; Admiral Sir Dudley Pound; and Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal—drafted a detailed report for consideration by Churchill and Roosevelt. Use of “the Portuguese Atlantic Islands would be of outstanding value in shortening the war by convincing the enemy he has lost the Battle of the Atlantic,” they wrote. And, said the British military chiefs, the “protection of convoys in the central Atlantic is essential to sustain Allied operations in the Mediterranean and to keep the buildup for [Operation] Overlord [the planned liberation of Europe] on schedule.” The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff endorsed the report and presented it to FDR and Churchill to adopt as official policy.

The prime minister cabled his War Cabinet in London that he and FDR were discussing a combined front to pressure Salazar and that they would present him with an ultimatum to allow an Allied occupation of the islands. If diplomacy failed, they would use force. The British and Americans approached the Azores question differently. Churchill’s cabinet advocated waiting to see if ongoing negotiations failed, while the Americans were characteristically impatient.

Admiral Ernest J. King, the irascible U.S. Navy commander in chief who was more concerned with operations in the Pacific Theater than in Europe, suggested that the British seize the islands and build an antisubmarine base there. Roosevelt recommended sending to the Azores an army division, 400 antiaircraft guns, 14 fighter squadrons, and 10,000 men to build an air base. Meanwhile, the U.S. State Department, “accustomed to sneezing whenever the Pentagon caught cold,” vacillated.

Churchill was pleased with the proposals, but his War Cabinet was horrified and convinced him to calm Washington down. Additional restraint was exerted by Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden on Churchill and by General George C. Marshall, U.S. Army chief of staff, on FDR. Some headway had been made by this time with Salazar, who was about to agree to British bases in the Azores. He wanted to keep the Americans out of the picture for two reasons: first, that once in the Azores, they would stay; second, how to explain it to Germany, with which he was trading.

Persisting with diplomatic maneuver and ever mindful of history, Churchill rose in the House of Commons on October 12, 1943, to announce that he had invoked the treaty signed by King Edward III and King Fernando and Queen Eleanor of Portugal in 1373 to authorize an operation to protect the Azores. Relishing every moment of the historic event, the prime minister took puckish pleasure in springing on a surprised Parliament an ancient treaty that few even knew existed.

“As this soaked in,” Churchill reported, “there was something like a gasp. I do not suppose any such continuity of relations between two powers has ever been, or will ever be, set forth in the ordinary day-to-day work of British diplomacy.” He noted that the 1373 accord had been reinforced in various forms by treaties in 1386, 1643, 1654, 1660, 1661, 1703, 1815, 1899, 1904, and 1914.

Churchill told the Commons that Salazar’s government had accepted the British request for “certain facilities in the Azores which will enable better protection to be provided for merchant shipping in the Atlantic.” The agreement, said the British leader, “is of a temporary nature only, and in no way prejudices the maintenance of Portuguese sovereignty over Portuguese territory.” On that evening of October 12, 1943, the Lisbon newspapers carried the full text of Churchill’s statement along with an explanation by the Portuguese government that the Azores accord would not compromise the nation’s neutrality.

Churchill dubbed the occupation of the Atlantic islands Operation Alacrity.

Premier Salazar had acted outwardly neutral to justify his refusal to grant the Germans submarine bases in the Azores, while continuing to trade with them. Because of a Royal Navy blockade, Nazi Germany had to obtain tungsten—a metal necessary to harden steel and for use in lamp filaments—on the European continent. Portugal, Spain, and Sweden were the only suppliers that could ship the metal overland to Germany. The Portuguese production of tungsten was by far the most important—3,000 tons a year.

To the dismay of the Allies, Salazar insisted that trade with Germany was necessary to maintain his country’s neutrality and not damage its poor economy or antagonize the Nazis. Like Spain’s wily Franco, he was careful not to provoke the ruthless and unstable Hitler, who had harbored designs on the Iberian Peninsula early in the war.

A Nazi occupation of Portugal would mean U-boats sneaking out unhindered from bases on its Atlantic coast, and this was a consequence too calamitous for Churchill to contemplate. “The U-boat attack was our worst evil,” he said later. “It would have been wise for the Germans to stake all upon it.” When Salazar had consulted with Britain early in the war on what was expected of him, Churchill agreed to help modernize the Portuguese Army. But he urged Salazar to stay out of the war.

Throughout the war, the Allies found Salazar difficult to deal with. The only son of a small landowner in the scenic province of Beira Alta, he was educated in a seminary and at the historic University of Coimbra before becoming an economist and professor. He served as finance minister of Portugal and was elected prime minister in 1932. He became a virtual dictator. A bachelor and lifelong supporter of the Catholic Church, “the little gray man” lived an austere life. A British diplomat observed that he “lived the plainest of lives, indifferent and indeed hostile to any ostentation, luxury, or personal gain.”

Urbane British Foreign Secretary Eden was driven to despair many times while dealing with Salazar and spoke of “conduct incomprehensible in an ally.” Yet the Portuguese leader was in an unenviable position. His chief concern was to maintain a pose of proper diplomatic behavior and not give the Germans an excuse to invade his vulnerable, strategic territory. Although the Azores occupation made Portugal a co-belligerent, an outward veneer of neutrality was maintained. When 11 American planes were obliged to land at Lisbon in January 1943, they were impounded and their crews interned.

Salazar also had to be wary of his Spanish neighbor, for, at the beginning of the war, Franco had signed the Anti-Comintern pact aligning Spain with the Axis powers.

Convinced that the fascist nations would win the war, Franco had warned Salazar that any Allied landing on Portuguese territory would be considered an act of aggression and that Spain would be forced to take steps in her own defense. The Portuguese premier needed to be careful, for if the Nazis did not invade his country, then their Spanish supernumeraries might arrive instead. At a meeting in Seville in February 1942, the shrewd Salazar convinced Franco to remain neutral and start thinking about the possibility that the Allies could prevail. The Anglo-American invasion of North Africa on November 8, 1942, assured Franco that his Portuguese counterpart was on the right track.

In the meantime, the British War Cabinet feared that even if Spain ostensibly remained cordial to Portugal, Franco would be hard pressed to deny Hitler the right to send his forces through the Pyrenees and into Gibraltar and Portugal. As it turned out, Franco emerged as one of the unsung heroes of World War II. He was the only national leader on the European continent to stand face to face with Hitler and reject his proposals. If he had not done so, German armies would have invaded Iberia, the Mediterranean would have been closed, and the German general staff would not have gone ahead with the June 1941 invasion of Russia, which proved to be the Nazis’ undoing.

The Allied-Portuguese treaty of October 1943 was the wedge that allowed the construction of the Lajes airfield on the island of Terceira in the Azores. At the first Quebec Conference on August 13-24, 1943, Churchill and Roosevelt had agreed that British units should enter the islands with the consent of Portugal, followed by the Americans two weeks later. Portugal had signed an official agreement giving Britain the use of Azores bases on August 18.

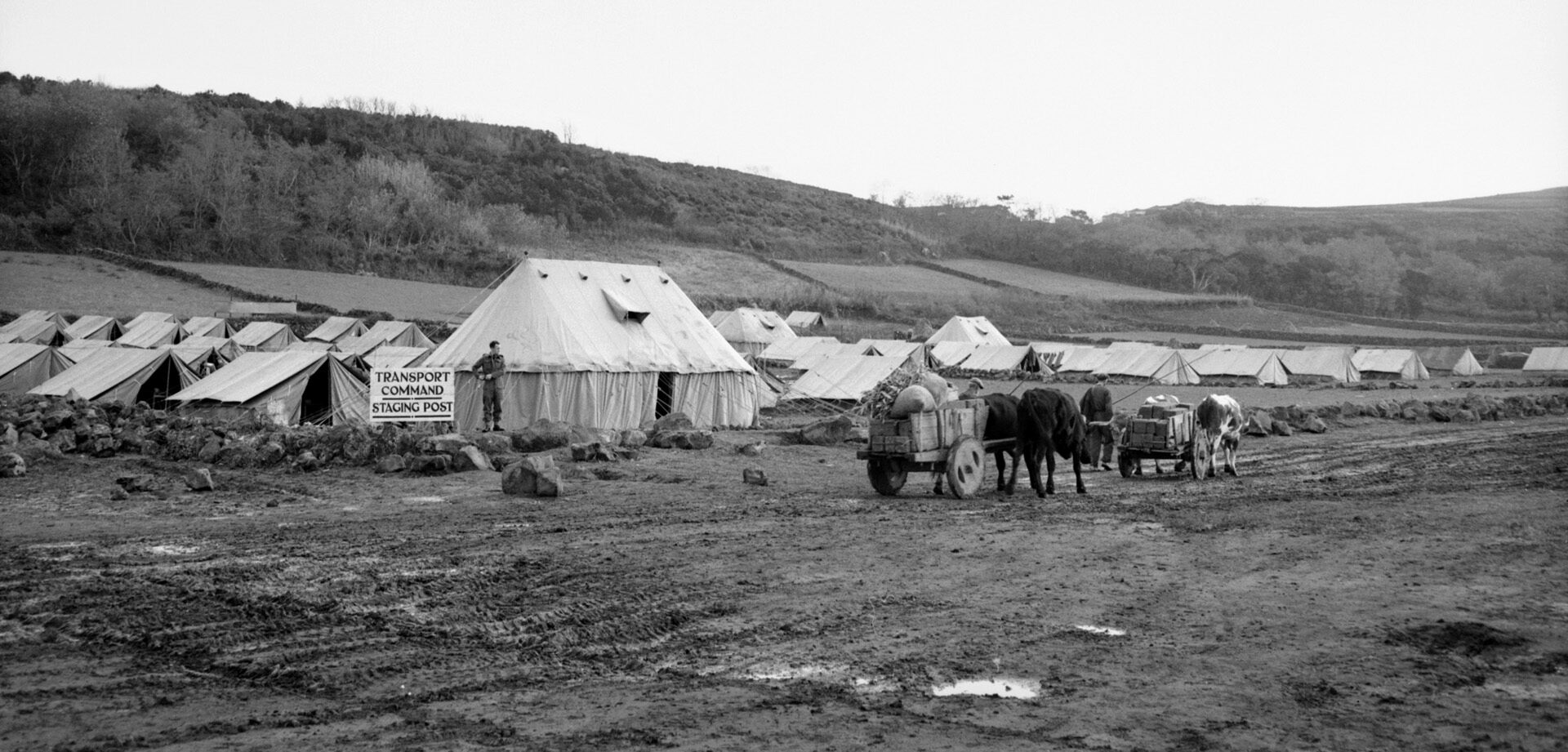

Early in October 1943, a combined British task force led by Air Vice Marshal G.R. Bromet sailed from Liverpool to the Azores. Three small convoys were comprised of the troop carrier HMT Franconia, three escorting destroyers, the escort aircraft carrier HMS Fencer, anti-submarine trawlers, and landing craft. The force carried 3,000 officers and men drawn from the Royal Engineers, the Royal Air Force, and the Royal Navy. After a week of sailing through rough weather while eluding U-boats, the so-called 247th Air Group disembarked at Angra do Heroisma to start work on the Lajes air base.

Immediately after landing in Terceira, work started on building a 6,000-foot-long runway that would serve RAF Coastal Command four-engine Boeing B-17 bombers and heavy transport planes. The British airmen, sappers, and sailors were helped by local laborers. The landing strip was finished quickly, blessed by a local Roman Catholic priest, and ceremonially opened by the governor of Terceira. Air Vice Marshal Bromet moved three squadrons of Coastal Command B-17s and Lockheed Hudson twin-engine medium bombers into Lajes, and air patrols from the islands started.

The Azores gap was closed, the Atlantic was no longer a graveyard for Allied ships, and German U-boat losses mounted dramatically. British, Canadian, and American naval units—now aided by antisubmarine patrol bombers based in the Azores—had turned the tide in the long, costly Battle of the Atlantic. The director of the U.S. Bureau of Yards and Docks’ Atlantic Division reported, “Suffice it to say that with the inauguration of the Azores patrols, shipping losses fell off to such an extent as to become almost negligible; at the same time, the men concerned wanted for little.”

A U.S. Navy report said later, “Allied acquisition of the Azores as a base was a decisive blow against German submarine warfare.”

Twenty-three U-boats were sunk in October 1943, and in November and December only nine merchant ships were lost out of 2,468 that sailed in 64 North Atlantic convoys. At the same time, 25 more German submarines went to the bottom. Admiral Karl Dönitz called off his wolfpack strategy and ordered the remaining U-boats to disperse more widely.

In January 1944, officers and men of the U.S. 96th Naval Construction Battalion (Seabees) and the U.S. 928th Engineer Aviation Regiment landed on the island of Terceira.

When a U-boat intercepted the Portuguese merchant steamer Serpa Pinto in the mid-Atlantic on May 26, 1944, Prime Minister Salazar considered clamping an embargo on tungsten shipments to Germany. He was also under intense diplomatic pressure regarding the exports from the Allies, particularly Brazil, which charged that tungsten sent to Germany was contributing to casualties among its 25,000-man expeditionary force fighting with General Mark W. Clark’s U.S. Fifth Army in the Italian campaign. Salazar relented and agreed in June 1944 to halt all tungsten shipments to Germany. It was a hard decision that meant the loss of two million pounds in revenue and 100,000 jobs for his impoverished country.

Meanwhile, the facilities in the Azores were expanded and improved, and agreement was reached in November 1944 for construction of a U.S. air base on Santa Maria Island. By now, with the archipelago a “shining Allied beacon in the Atlantic,” neutral Portugal was playing a key role in the war against tyranny. Besides hunting down U-boats, British and American patrol bombers from the Azores shepherded to England convoys of U.S. and Canadian troops, weapons, and matériel crucial to the liberation of Europe.

Nevertheless, Salazar’s Portugal maintained its neutrality until the end of the war. It was one of two nonbelligerent countries (Ireland was the other) that flew flags at half mast after Hitler’s suicide in April 1945.

Author Michael D. Hull has written frequently for WWII History on a variety of topics. He resides in Enfield, Connecticut.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments