By Victor Kamenir

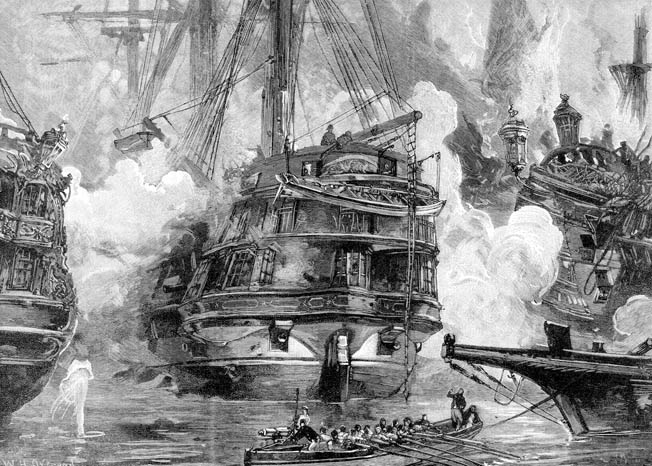

At 2 PM on October 20, 1827, Allied squadrons sailed into the Bay of Navarino on the west coast of the Peloponnese peninsula. The warships arrived in two long columns. Commander-in-Chief Vice Admiral Edward Codrington intended to enforce an armistice on the Ottoman navy during the long drawn out Greek War of Independence. Codrington, aboard the 84-gun HMS Asia, had issued orders not to fire first on the enemy. Although outnumbered by a swarm of mostly smaller, poorly armed warships, the Allies had a number of ships of the line. The atmosphere in the harbor was terribly tense.

A group of Egyptians was preparing a fireship, and one of the British frigates dispatched a boat with men who bore a message instructing the enemy to stop the hostile act. Musket shots rang out between the two parties. An unidentified Turkish corvette swung into action, firing two shots at the French flagship Sirene. Soon the harbor roared with guns as other ships joined the spreading fight at the entrance to the Peloponnese harbor. The struggle for control of Greece was heating up again.

As the Napoleonic Wars drew to a close at the beginning of the 19th century, a wave of nationalist movements swept through eastern and southeastern Europe. Among the peoples struggling for their national identity and independence were the Greeks, who had been living under the heel of the Ottoman Empire since the late 14th century.

In February 1821, a clandestine Greek organization called The Society of Friends, or Filiki Eteria, led an open rebellion against the Ottoman rule. Vicious fighting spread throughout Greece, with no quarter given on either side. Especially heavy fighting took place in the historic Peloponnese peninsula in the south, the heartland of the rebellion. As the fortunes of war shifted back and forth, in early

1824 Sultan Mahmud II turned to Muhammad Ali of Egypt for assistance. Even though nominally under Ottoman suzerainty, Muhammad Ali was an independent ruler in all but name. Moreover, unlike the sultan’s steadily deteriorating military machine, Muhammad Ali possessed an army and a navy trained, equipped, and advised by French military officers. In return for his assistance, the sultan granted Muhammad Ali the island of Crete, while his eldest son Ibrahim was to receive the Peloponnese.

Ibrahim, with a 16,000-strong corps of ground forces supported by an Egyptian naval squadron invaded the Peloponnese in February 1825. He quickly conquered the western part of the peninsula but was not able to secure the east, the stronghold of the rebel government. Despite some successes on land and sea, by 1827 the situation became dire for the rebellion. The fighting turned large swaths of the bountiful countryside into barren wastelands with charred trees, burned-out homes, and barren fields. In some places the landscape was even littered with the bleached bones of the unburied dead who were victims of the slaughter wrought by conquering Egyptians.

Weary of the recently ended upheavals of the Napoleonic Era, which saw many a monarchic house overthrown, major European powers were initially either ambivalent or openly hostile to the Greek revolution; however, the political atmosphere in Europe had changed substantially by 1827. Even though the British and French governments were inclined to support the Ottoman status quo, public opinion throughout Europe was highly favorable to the Greek struggle and placed increasing pressure on their governments. Various Philhellenic committees financed and equipped 1,200 European volunteers, along with a few Americans, to fight for the Greece cause. The Greeks appointed a number of prominent British expatriates to important positions in their military forces.

Russia under Tsar Alexander I initially maintained a neutral stance. After Alexander’s death in 1825, his younger brother Nicholas I ascended the Russian throne. The new tsar adopted a decisively aggressive stance toward the Ottoman Empire as the protector of its Christian subjects, who were mainly the Balkan Slavs and the Greeks. One key consideration was Russia’s strategic aim of extending her influence into the eastern Mediterranean and southeastern Europe.

In their efforts to oppose Russia’s growing power, the British and French governments brought their combined political will to bear on Russia, forcing the latter to agree to a joint effort in attaining Greek autonomy while at the same time preserving Ottoman territorial integrity.

On July 6, 1827, Britain, France, and Russia signed the Treaty of London, which called for an immediate halt of combat operations between the Greeks and the Ottoman Empire. The Allies offered to act as mediators to reach an armistice that would eventually lead to Greek autonomy under continuing suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. On August 29, the Ottoman government formally rejected the Treaty of London, while the Greek provisional government accepted the treaty on September 2.

To enforce the treaty, the three Allied powers formed a joint naval expedition under overall authority of Vice Admiral Sir Edward Codrington, commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet.

Codrington was a veteran with 44 years of experience at sea. He had distinguished himself commanding a frigate at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, and he was very sympathetic to the Greek cause given that he was a member of the London Philhellenic Committee.

The man in charge of the French squadron was Rear Admiral Marie Henri Daniel Gauthier, Comte de Rigny. A capable sailor, his tactful manners served well to counterbalance Codringtont’s gruff persona. A significant portion de Rigny’s distinguished carreer was spent fighting on land as a member of Napoleon’s elite Sailors of the Guard. The Russian squadron was under the command of Rear Admiral Login Petrovich Heiden, a Dutch nobleman in the Russian service who was a solid and reliable officer.

Codrington’s superiors anticipated that the Turks might reject the offer of mediation, and they had issued instructions to him setting forth a specific course of action from that point forward. “In the event anticipated of the refusal of the Porte to admit the mediation and to consent to an armistice, you will then, in the first place, have to enter on friendly relations with the Greeks, and next to intercept every supply sent by sea of men, arms, destined against Greece and coming either from Turkey or Africa in general,” stated the instructions. Codrington was to enforce the armistice without fighting, but once all other means had been exhausted, he was cleared to use military force.

On September 25, while the Russian squadron was still en route to the Mediterranean, Admirals Codrington and de Rigny met with Ibrahim at his base near the small town of Pylos, located on the Bay of Navarino on the southwestern shore of the Peloponnese. At this conference, Ibrahim was advised of Codrington’s instructions. Ibrahim agreed to an armistice, pending further instructions from Constantinople. Satisfied with the outcome of the meeting, the two Allied squadrons departed for the British-held island of Zante, leaving behind a frigate to observe the Ottoman fleet at Navarino.

While Ibrahim initially abided by the agreement, Greek forces in the north of the peninsula, commanded by Sir Richard Church and Lord Thomas Cochrane, expatriate British officers in the Greek service, continued conducting active military operations against the Turks. Codrington appealed to them to desist but to no avail. After launching an unsuccessful protest to Codrington, Ibrahim took matters into his own hands. He tried on October 1 and again three days later to break out from Navarino with part of his squadron but was intercepted both times by Codrington and de Rigny and forced to return to Navarino.

On October 13, the Russian squadron finally joined Codrington after a long voyage from the Baltic Sea. De Rigny’s French squadron linked up later the same day. In contrast to existing tenions between Codrington and de Rigny, whom Codrington considered more of a diplomat than a fighting sailor, the British commander struck an instant friendship with the Russian commander, Admiral Heiden.

On October 17, under the flag of truce, the British frigate Dartmouth entered the Bay of Navarino with a letter signed by the three admirals that contained strict language about Ibrahim not adhering to his commitments. The British envoy was met by Moharram Bey, who claimed not to know where Ibrahim was and, therefore, was not able to forward the letter. At that time, Ibrahim was conducting operations at Modon farther south along the coast.

On October 18 the three admirals gathered on Codrington’s flagship Asia for a confrerence. The Allies felt they had to force the issue because they could not maintain the blockade of the Ottoman fleet in the Bay of Navarino throughout the winter due to inclement weather. “It was decided that all the vessels of the Allied fleet were to enter the Bay of Navarino, drop anchor near the Turkish fleet, so that by presence and deployment of the Allied squadron to force Ibrahim to concentrate his force at this location and give up any new attempts against the shores of Morea [Peloponnese] and Greek islands,” wrote Heiden.

While the intent of the Allied commanders was to intimidate Ibrahim with the presence of their squadrons, each of the three admirals had different expectations of the outcome. The Russian Heiden was spoiling for a fight to punish Ibrahim as the tsar had instructed him to do. De Rigny was convinced that a fight was unavoidable. Only Codrington, although pessimistic, was still hoping for a peaceful outcome. Their decision was presented in a letter to Ibrahim’s representative on October 19.

The classification system of fighting ships of the British Royal Navy in the 19th century was similar to those of other countries. Typically, ships carrying 20 or more guns were ranked according to their size and armament, from sixth rate being the lowest to first rate mounting 90 or more guns. In addition to allocated guns, most ships possessed additional guns, known as bow and stern chasers, which were lighter pieces mounted on swivels; additional guns were mounted on open forecastles and quarterdecks. Thus, a ship designated as a 74-gun carried 80 or more. Rated below ships of the line were double and single-deck frigates, corvettes, and brigs.

Sloops-of-war and cutters, mounting fewer than 20 guns, were considered unrated. The largest Allied ships at Navarino carried 70 or more guns and had a crew of between 500 and 650 men. The ships were armed with a combination of long 12-pounder, 24-pounder, and 32-pounder guns, supplemented by carronades, shorter and larger caliber guns particularly devastating at shorter ranges.

The typical tactical formation was the line, which was composed of ships capable of delivering and withstanding large amounts of damage. Fighting on open seas, each combatant’s goal was to cross in front of the enemy line—thus giving the name of crossing the T—so as to take the enemy line under the raking fire. The raking fire would then be delivered at the stern or bow, the weaker parts of the ships.

Once at anchor, a ship’s alignment, but not position, could be changed by the use of springs (in the form of cables attached to anchor chains). By hauling on springs, a ship could be turned to deliver broadsides against multiple opponents. Naval gunfire was typically inaccurate unless the combatants closed to a very short range where it was impossible to miss. Gunpowder was expensive and few captains could afford to expend it in practice. The main advantage of European crews, the British in particular, came from extensive use of firing drills, long-service experience, and superior ship-handling skill of the officers. Many of the crew and officers on the British and French ships converging on the Bay of Navarino were veterans of the Napoleonic Wars.

An additional vessel type, used extensively and successfully by the Greeks and adopted by the Ottomans, was the fireship. A fireship typically was a mid-to-small-size merchantman or an old ship that was packed with explosives and combustibles, set on fire, and either steered or allowed to drift toward the enemy. A few men remained on the vessel to ensure it reached its intended target. They jumped off the fireship just before it made contact.

The British and Russian ships were newer and in good repair; however, three French ships of the line, the Breslau, Scipion, and Trident, were in such poor shape that Admiral de Rigny flew his flag in the frigate Sirene.

The large natural harbor in the Bay of Navarino provided Ibrahim with a convenient location to receive supplies and reinforcements from Alexandria, Egypt. The bay, which is approximately three miles long and less than two miles wide, is partially shielded by the long and narrow Sphacteria Island. The entrance to the bay could be gained by a narrow and shallow passage to the north of Sphacteria, partially impeded by a small islet, or around the southern tip of Sphacteria, the commonly used approach. The Fort of Navarino and the shore batteries on the southern tip of Sphacteria Island guarded the southern entrance.

The Ottoman fleet that gathered at Navarino was composed of two distinct elements: the Imperial Turkish squadron from Constantinople and the combined squadron from Alexandria, Egypt, composed mainly of Egyptian vessels and including small contingents from Tunisia and Tripoli. Rear Admiral Tehir Bey, Ryale-i Hümayun, was the acting Ottoman commander. He is often incorrectly identified as the Kapudane-i Hümayun, the Grand Imperial Admiral. In practice, he was subordinated to Ibrahim’s command. Vice Admiral Moharram Bey, the Patrona-i Humayun, led the Egyptian squadron from Alexandria.

The ships making up the Imperial Ottoman portion of the combined Turco-Egyptian fleet were in poor repair with many impressed Greek sailors aboard, many of whom were later found chained to their stations. The Egyptian squadron was the largest and best equipped component in the Ottoman fleet. In efforts to modernize his military, Muhammad Ali hired expatriate French officers to train his army and navy and purchased a number of vessels newly built in France and Italy. Their crews included many experienced sailors from North African states and the Greek islands. The French naval contingent was headed by Captain Jean-Marie Letellier, a veteran of Trafalgar, who served as Moharram Bey’s French adviser. The French officers officially served in an advisory role on the Ottoman ships, but in reality enjoyed an almost dual authority. Captain Letellier served on Moharram Bey’s flagship Guerrière, built in France and renamed Murchid-i-Djihad (Warrior) in the Ottoman service.

The number of combat vessels attributed to the joint Turko-Egyptian fleet varies among different sources, but the number is considered to be between 65 and 85 plus approximately 40 armed troop transports. Only the ships of the line and the double-deck frigates and a few singledeck frigates have been positively identified by name.

Three days of diplomacy between Moharram Bey and the Allied admirals gave Codrington an opportunity to learn the disposition of the Ottoman fleet. In a plan prepared by Captain Letellier, the Ottoman vessels were arranged at anchor in a horseshoe formation with the open end facing the entrance to the bay. The vessels were deployed in a checkerboard formation of three lines, with the ships of the line and larger frigates in front, smaller frigates in the second line, and corvettes and brigs in the third. The checkerboard formation permitted the smaller vessels in the back to fire through the gaps between the vessels in front. This disposition allowed the Ottomans to concentrate maximum firepower on the middle of the bay. Fireships were positioned at both ends of the horseshoe, under cover of artillery batteries at the Fort of Navarino and on the southern tip of Sphacteria Island. Ibrahim’s headquarters, minus Ibrahim himself, were located on a small hill near the Fort of Navarino.

Moharram Bey, the senior officer in Ibrahim’s absence, flew his flag on the 60-gun Egyptian frigate Guerrière, and was in command of the left wing. Tahir Bey, commanding the right, flew his flag on the Imperial Ottoman ship of the line Ghyu h R wan. The front line of the Ottoman formation comprised approximately 20 ships, with the largest ships in the middle. They were the Ihsania, Surya, Guerrière, Ghyu h Rewan, Fahti Bahri, Burj Zafer, Leone, and approximately 12 other frigates.

Codrington’s plan was to drop anchor inside the horseshoe, with the British vessels in the center of the Allied formation, and the French and Russians to the right and left, respectively. The British frigate Dartmouth and several smaller vessels were to position themselves behind the Allied formation to deal with the Ottoman fireships on the flanks. This was a very risky disposition, as the Allied ships entering the bay would not only be exposed to fire from shore batteries, but also experience concentrated Ottoman naval gunfire in the middle. Also, the wind was blowing from the southwest, straight up the bay, which would make a possible Allied withdrawal extremely perilous.

Knowing that the majority of Egyptian vessels with their French advisers were located on the Ottoman left flank, Codrington positioned French naval ships opposite the Egyptians. The belief was that the French officers on board the Egyptian vessels would not fight against their countrymen. This theory bore fruit. De Rigny was able to persuade these French officers to come ashore on October 19 so that, in the event of a battle, they would not have to fight their own countryman.

The Allies had 10 ships of the line, whereas the Ottomans had only three. But to its advantage, the Turco-Egyptian squadron had seven double-deck frigates to the Allies’ one double-deck frigate. French navy. Captain Letellier remained on board of Moharram Bey’s flagship, but he left when the ship opened fire.

In number of guns alone, 2,200 to 1,200, the Ottomans seemed to have the advantage, but the British guns were of heavier caliber and better served. The Allied starboard line included the Asia, Genoa, Albion, Sirene, Trident, Scipion, and Breslau, while the port column consisted of the Azov, Gangut, Iezekiil, Aleksandr Nevski, Provornyi, Elena, and Kastor. The Talbot and Armide were on the inner side of the starboard line. The Dartmouth and some of the smaller craft likely were on the outer side toward the head. The British frigates Glasgow and Cambrian and the Russian frigate Konstantin were coming up from the south.

Despite the growing tensions, Codrington had not expected battle. His Marine bandsmen were on the poop deck at the time, and his crew had not fully prepared for action by clearing all possible space for guns.

The Allied entry into the bay on October 20 did not elicit a hostile response from the Turks. A gun at the fort fired a blank shot and Captain Pierre Bernard Milius of the Scipion recorded that the Turks “sat on the battlements smoking their pipes.”

At 2:10 PM, Asia anchored opposite of Moharram Bey’s flagship Guerrière and two other frigates. A boat rowed from the shore and an Ottoman official came onboard Asia, stating that the Allies did not have permission to enter the bay and that they must withdraw immediately. Codrington replied that he did not come to ask permission but to give orders. He warned the official that if the Ottoman ships opened fire, they would be destroyed. After Codrington’s abrupt dismissal, the Turkish official returned to the shore and quickly went to the tent on the hill. Shortly afterward, “a red flag was hoisted at the tent and a gun fired—unshotted,” wrote Codrington.

Shortly thereafter, Captain Thomas Fellowes, commanding the frigate Dartmouth, observed a boat go from the shore to one of the fireships and a man climbed aboard. Being very close, Fellowes could see that preparations were being made to light the fireship. He sent a boat under Lieutenant Spencer Smyth demading that the Ottomans stop what they were doing. Instead, the Ottoman sailors opened musket fire and lit the fireship. Several British sailors in the boat were wounded and the coxswain was killed.

Fellowes sent an additional boat commanded by Lieutenant G.H.W. Fitzroy to take the fireship in tow and remove it to a location where it would not pose danger to the Allied ships. As the second boat approached the fireship, additional musket shots rang out, killing Lieutenant Fitzroy. In reply, Captain Fellowes gave orders to his marines to provide covering fire for the two boats. As the two vessels exchanged musket fire, the French flagship Sirene was entering the bay and its marines added their weight to the firefight.

Up to that point, the skirmish had involved only musket fire. But once the unidentified Turkish corvette fired its two cannon shots, one of which barely missed the Dartmouth and the other striking the Sirene, neighboring ships on both sides joined the fight. The cannonade quickly spread along the Allied line. As each Allied ship reached its assigned position, it dropped both anchors and opened fire.

Coming up opposite the Egyptian frigate Ihsania, Admiral de Rigny hailed the Egyptian, stating that he would not open fire if the Egyptian would hold his fire, too. However, at that same moment, Ihsania’s cannons fired on both Darthmouth and Sirene, killing a man on de Rigny’s ship. The French flagship returned cannon fire. At that point, the nearby shore batteries opened fire on Trident, which was following Sirene. “The engagement quickly became general,” wrote de Rigny.

The Scipion, the third French ship in line, became engaged against the shore batteries and the two Egyptian frigates on both sides. It also had to ward off the fire ship that had precipitated the battle. The burning fireship became entangled with the bow of Scipion, causing the fire to spread from the bowsprit. The gunners feverishly worked their cannons while some of the crew fought the fires. Several powder kegs exploded, causing horrible burns to many of the crew. As crew aboard the Scipion fought the fire, British and French ships came to the Scipion’s assistance, pulling the fireship away and sinking it.

Once the fire on the Scipion was out, she joined the Trident and Sirene in a collective effort to sink the Ihsania. Under relentless pounding, the Egyptian frigate was destroyed, exploding at 4 PM. The three French vessels then turned their attention to the fort, forcing its guns to fall silent.

Seeing the situation of the three leading French ships well in hand, Captain Jean de la Bretonniere of Breslau moved to the center of the harbor and dropped anchor at the junction of the British and Russian lines, with the Russian Azov on its left and the British Albion on the right. The three Allied ships became engaged with several Ottoman ships, including Tahir Bey’s flagship Ghyu h Rewan. De la Bretonniere’s initiative was greatly lauded by both the Russian and British commanders. In particular, Albion’s Captain John Ommanney credited de la Bretonniere for saving his ship from destruction.

As the fighting began to spread along the line, Moharram Bey sent a boat to Codrington’s Asia, stating his intentions to not open fire. But Moharram Bey did not remain unengaged for long. As the fighting continued, with Asia concentrating on Tahir Bey’s flagship, Codrington sent his Greek pilot Petros Mikelis to Moharram Bey to reaffirm the Egyptian’s commitment to remain neutral. For unknown reasons, an officer on Moharram Bey’s flagship shot Mikelis with a pistol through a porthole. Seeing Mikelis’s murder, Codrington turned some of his guns on Guerrière. The Azov also opened fire on Moharram’s Bey’s frigate, with the Russian marines sniping at the Ottoman sailors attempting to fight fires aboard their ship. Under relentless pounding by the two Allied ships of the line, Guerrière was severely damaged and forced to run aground to avoid sinking. Moharram Bey went ashore unscathed.

Dozens of ships at anchor fought each other at point-blank range. Men died not only from cannon shells and bullets but also by spreading fire and flying wooden splinters on their own damaged ships. Roundshot smashed through hulls, overturned guns, and showered men with deadly splinters. Meanwhile, grapeshot swept upper decks while sharpshooters did their best to pick off officers and gun captains.

Aboard the Asia, Admiral Codrington’s son Midshipman Harry Codrington was wounded in the right calf by a piece of flying iron railing from his father’s cabin, and a musket ball or a canister ball hit him in the right thigh. Additionally, a piece of wood dislocated his collar bone.

To preserve them, the British cannons were ordered double-charged and sailors grabbed muskets and joined the action. The heavier weight of the Allied guns and superior performance of their crews steadily turned the firefight into their favor. Despite the heavy damages suffered by the Allied ships, the carnage aboard the Turco-Egyptian ships was much worse. Men were being killed or wounded in the hundreds. Still, the Ottoman sailors fought on with immense bravery. As the Russian squadron began entering the bay, the smoke was already obscuring its progress. A ship of the line Gangut narrowly avoided collision with a burning Ottoman corvette, which blew up several minutes later. Dropping anchors in her predetermined position, Gangut quickly became engaged with three Ottoman frigates in the first line. The Izekiel, which arrived next, relieved some pressure on Gangut, which began engaging Ottoman corvettes in the second line. Around 4 PM, a fireship bore down on Gangut, but the Russian avoided it by maneuvering the springs and sunk it by gunfire. About half an hour later, a frigate fighting Gangut closed its portholes and sank without lowering its flag. “From the concussion of air, our ship shook in all of its parts,” wrote Lieutenant Aleksander Rykachev of the Gangut. “We were pelted with shells and glowing embers, causing the fire to break out in two places on our ship.”

The fire was quickly extinguished, and Gangut continued the fight. When an Ottoman frigate collided with Gangut, Captain Aleksander Avinov ordered his anchor chains cut so that his ship, entangled with the Ottoman one, drifted out of position and could not endanger other Allied ships. Once the two ships drifted out of line, Russian sailors holed the Ottoman ship and sunk it. By 5 PM, the Ottoman first line of ships was annihilated, being blown up, set on fire, sunk, or run aground. It was now time for the Allies to turn their deadly attention to the smaller Ottoman vessels in the second and third lines. With no chance to oppose the Allied capital ships, the smaller Ottoman vessels attempted to flee for the shore, yet the Allied heavy guns mercilessly hunted them down. An hour later the battle was over. The Allies had destroyed the Ottoman fleet. It was now time to tally the butcher bill. Aboard the Allied ships, doctors and medical orderlies worked frantically to save as many men as they could. Total Allied losses came to 174 men killed and 473 wounded. Of that number, the Russians lost 59 men killed and 139 wounded, the

British 74 killed and 206 wounded, and the French 41 killed and 128 wounded. The Allied flagships bore the brunt of the fighting and therefore suffered the heaviest casualties.

Other Allied ships suffering high numbers of casualties were the Russian Azov, which lost 91 killed or wounded, and the French frigate Armide, which lost 41 men, a disproportionally high number considering its smaller crew compliment.

Not a single Allied vessel was lost, even though all the capital ships suffered heavy damage. The three British ships of the line were mangled so extensively that they had to be returned to the United Kingdom for major repairs. “The Asia had 8 round shot in her bowsprit, 18 in foremast, 25 in mainmast, mizzen-mast dowsed, sanding and running rigging cut to pieces, lower yards useless, and 125 round shot in the hull, beside quantities of grape, canister, and musket shot,” wrote Midshipman Codrington. “I believe no round shot penetrated her side in the lower deck, and none through the main deck; there are several shot which have nearly penetrated and even pushed in the inner plank, but I think none got regularly through, except on the upper deck and through ports.” The Russian Azov received 153 hits, seven of them below the waterline, and the Sirene was heavily damaged as well.

The Allied squadrons remained vigilant at their battlestations throughout the night. Darkness was punctuated by exploding Ottoman ships, which were being destroyed by their own crews to keep them from falling into enemy hands. At one point, a burning and out-of-control Turkish frigate was bearing down on Genoa. Nearby Russian ships sunk it by gunfire. Ottoman vessels exploded, burned, or drifted lifelessly about the bay. To protect themselves from the danger of spreading fire, the Allied squadrons pulled away from them.

On the morning of October 21, Tahir Bey came aboard Asia. He was strongly advised that if he displayed any hostile intentions, the remaining Ottoman ships, as well as the fort, would be destroyed. The Ottoman admiral assured Codrington that no more fighting would take place. Later the same day, Ibrahim returned to Navarino to discover his fleet destroyed.

Since the exact number of Turco-Egyptian ships was not known, it is difficult to obtain accurate figures on the Ottoman losses. Ottoman ship losses amounted to one ship of the line, 12 frigates, 42 smaller ships, and all five fireships, according to Captain Letellier. The only fighting ships still afloat in the morning were one dismasted frigate, four corvettes, six brigs, and four schooners. Approximately 3,000 Ottoman sailors were killed and 1,100 wounded. Moharram Bey’s Guerrière was eventually repaired, as were another four or five frigates and several corvettes and brigs.

When the Allied squadrons sailed from the Bay of Navarino on October 25, Ibrahim still maintained a solid hold on the Peloponnese. With his expensive fleet destroyed and 13,000 French troops landing at the Bay of Navarino in April 1828, Egyptian ruler Muhammad Ali lost interest in the Greek affairs and recalled his son Ibrahim and his forces from the Peloponnese. Supported by French troops, the Greek forces cleared the peninsula of the remaining Ottoman strongholds by the end of 1828.

The events at Navarino led to another Russo-Turkish War in 1828 that ended in an

Ottoman defeat. Under the terms of the Treaty of Adrianople, the sultan accepted Greek autonomy as proposed in the Treaty of London, as well as ceded to Russia a large swath of territory in the Caucasus. However, the Greeks refused to accept anything short of full independence. Caving in to Allied pressure, the sultan formally recognized the new Kingdom of Greece in 1832. But the Allies would only accept the new state as a monarchy, not a republic. A suitable candidate for a monarch was found in Bavarian Prince Otto, who traced his ancestry to the ancient royal families of Greece. As King Othon I, he ruled the new kingdom, which was composed of the Peloponnese, central Greece, and some islands in the Aegean Sea. By this arrangement, the Ottomans retained a large part of Greece.

While public opinion in England was enthusiastic about the outcome of the battle, the British government was extremely displeased, for it was never the intention of the three Allied governments to completely destroy the Ottoman fleet. Codrington was blamed for exceeding his instructions and causing the events that precipitated the battle. Paying lip service to public opinion, the British government awarded Codrington the Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath. However, once public enthusiasm died down, Codrington was quietly dismissed from service in August 1828. Three years later, he returned to service. Codrington eventually was promoted to Admiral of the Red; that is, commander of the red squadron, in 1837 and Commander-in-Chief at Portsmouth in 1839.

Admiral de Rigny went on to a political carreer, becoming the Minister of Marine and Foreign Minister. Admiral Heiden finished his military carreer as the military governor of Revel. Young Harry Codrington fully recovered from his wounds and eventually became an admiral himself.

Ibrahim later succeeded his father and eventually became ruler of an independent Egypt. In a strange turn of events, when Ibrahim rebelled against his Ottoman master, invading Turkey in February 1833, Sultan Mahmud II turned to the Russian government for protection.

In a twist of fate, Lieutenant Pavel Nikhimov, who served aboard Azov at Navarino, fought the British, French, and Turkish as an admiral during the Crimean War. Opposing him among the British forces in Crimea was Maj. Gen. William Codrington, the second son of Admiral Sir Edward Codrington.

The Battle of Navarino marked the end of the wooden sailing era. Three weeks before the battle, the Greek sloop Karteria, a steam warship commanded by British expatriate Captain Frank Hastings, gained a formidable reputation by sinking nine Ottoman ships in one engagement three weeks before the Battle of Navarino. The event was significant because it marked the first combat action of a steam warship. A new age in naval warfare had dawned.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments