By Eric Niderost

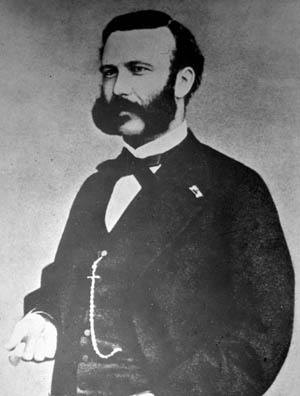

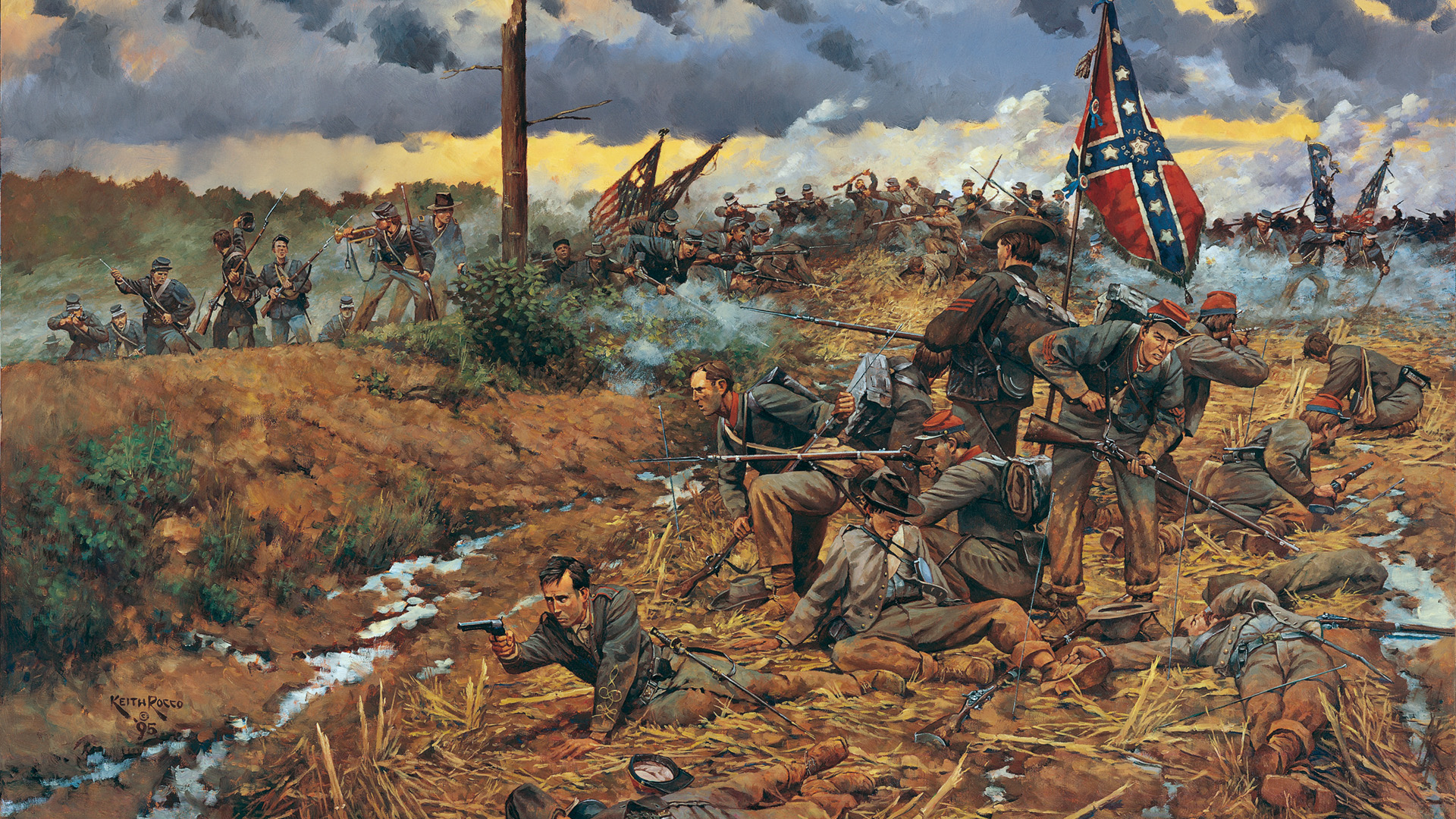

Henri Dunant, a 31-year-old Swiss banker, was a more or less inadvertent eyewitness to the Battle of Solferino in June 1859, and its myriad horrors left an indelible impression on him. Like most people of the Victorian Age, Dunant had a romantic notion of war, reinforced by the epic battle paintings common to the period. Before the battle began, he was actually looking forward to the spectacle about to unfold before him like an epic sporting event

The ensuing 15-hour slaughter stripped him of all such delusions. War was not just colorful battle flags waving in the breeze, but death, dismemberment, blood, and agony. Thoroughly and permanently shocked, Dunant did what he could to tend the wounded after the battle, organizing volunteers from anyone who was willing to roll up his sleeves and help. He recruited Italian peasants and even English tourists to help him on his mission of mercy.

Dunant was changed by what he had seen at Solferino. He felt there must be a better way to aid sick and wounded soldiers. He wrote an empassioned pamphlet, A Memory of Solferino, that graphically detailed the sufferings of the wounded. It is powerful reading even today, and its publication caused a sensation throughout Western Europe.

Back in his native Geneva, Dunant began to develop ideas on how to aid the victims of battles. It took time, but in 1863 Dunant and four other Geneva residents formed a committee that became the ancestor of the International Red Cross, named in honor of their native country’s flag. Within a few years there were national committees devoted to the aid of the wounded in nearly every country in Europe, all sprung from the seed that Dunant and his colleagues had planted in 1863.

Back in his native Geneva, Dunant began to develop ideas on how to aid the victims of battles. It took time, but in 1863 Dunant and four other Geneva residents formed a committee that became the ancestor of the International Red Cross, named in honor of their native country’s flag. Within a few years there were national committees devoted to the aid of the wounded in nearly every country in Europe, all sprung from the seed that Dunant and his colleagues had planted in 1863.

Dunant devoted himself completely to the Red Cross movement, but his single-mindedness came at a price. He neglected his business affairs to the point that he went bankrupt and heavily in debt. Still, during his years of greatest fame, between 1863 and 1867, he was an international celebrity of a sort, honored for his humanitarianism. Louis Napoleon supported the movement, and Empress Eugenie met personally with Dunant.

The Franco-Prussian War in 1870-1871 saw the first fruits of Dunant’s labor, as volunteers did much to ease the suffering of soldiers on both sides of the conflict. American-born nurse Clara Barton was one such volunteer, and she bore the Red Cross’s message home with her, founding the American Association of the Red Cross in 1881.

Meanwhile, Henri Dunant drifted into obscurity. Thirty years later, when he was an old man, poverty-stricken and sick, he found refuge in a hospital in Heiden, Switzerland. A reporter rediscovered him there in 1895, and he enjoyed some long-delayed honors in the last years of his life, including a share of the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901. He died in 1910, but the humanitarian movement he founded lives on.

Today, there are over 185 Red Cross and Red Crescent societies all over the world giving aid and comfort to those in distress. The Red Crescent became the symbol of the movement for Muslim countries, an obvious nod to history. In Islamic countries, a red cross is still a touchy symbol, too similar to the emblem worn by European crusaders in the Middle Ages.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments