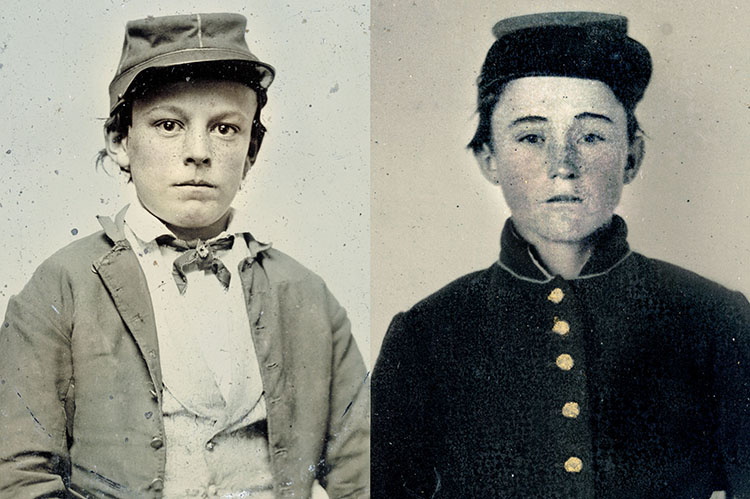

“All wars are boyish, and are fought by boys,” author Herman Melville wrote. That was certainly true of the American Civil War, when some 70 percent of the troops on either side were 23 or younger, and the median age for a soldier was 18. The very nicknames of the generic combatants reflected their youthfulness: Billy Yank and Johnny Reb. Many were not even shaving yet.

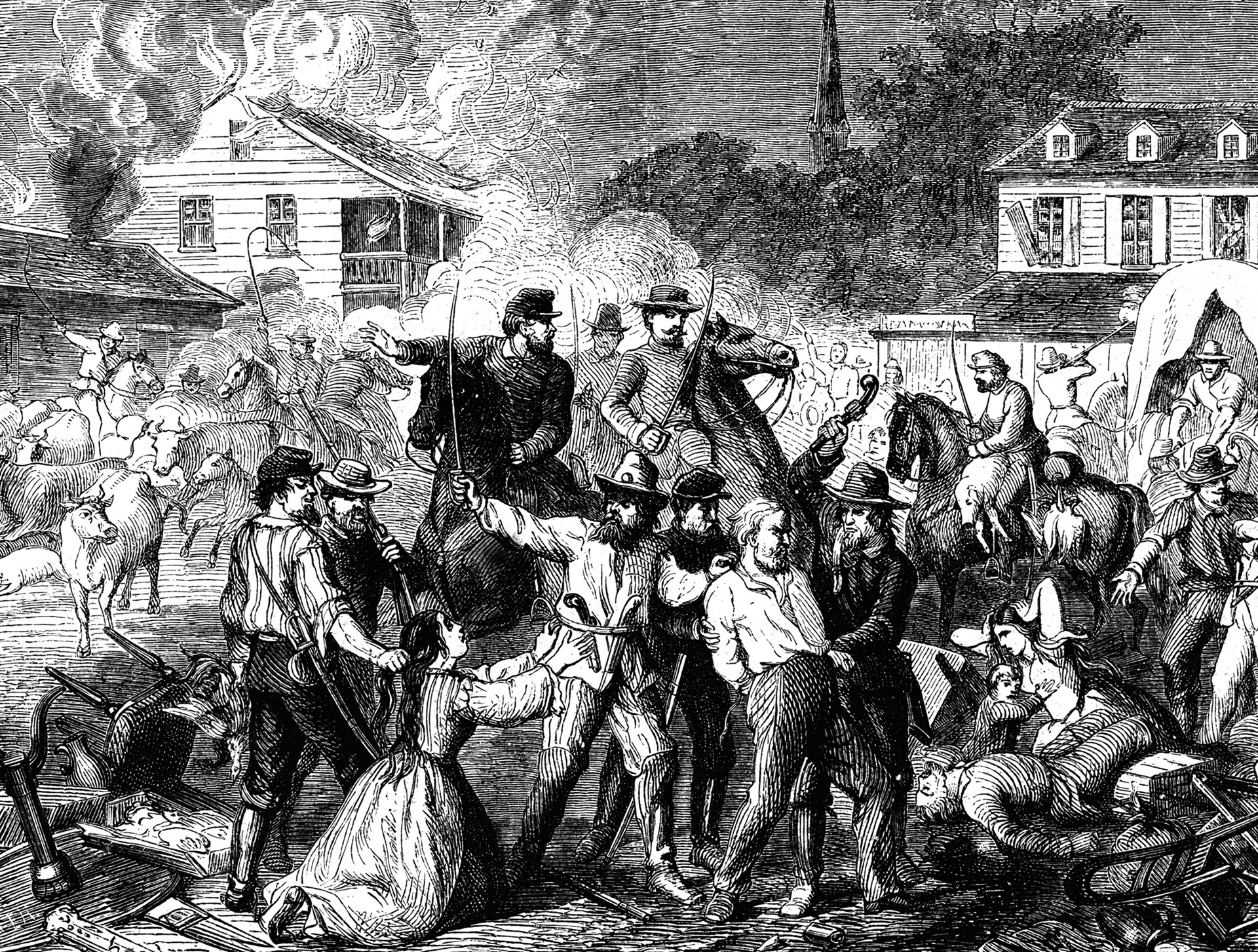

As with most wars, the young Civil War soldiers enlisted for a variety of reasons: patriotism, peer pressure, adolescent idealism. Most were motivated, at least at the beginning of the war, by a vague desire to “see the elephant,” as the popular catchphrase then had it. The “Boys of ‘61” believed that the war would be great fun. Thoughts of death were the farthest things from their minds. Smart new uniforms, crackling flags, and swooning ladies were the grist for adventure. The true political underpinnings of the war were understood dimly, if at all.

Private Ralph Smith of the 2nd Texas Infantry caught the glowing spirit of the times. “I wish I were able to describe the glorious anticipation of the first few days of our military lives,” he wrote, “when we each felt individually able to charge and annihilate a whole company of bluecoats. What brilliant speeches we made, and the dinners the good people spread for us, and oh, the bewitching female eyes that pierced the breasts of our gray uniform, stopping temporarily the heartbeats of many a fellow.”

The gaiety usually did not survive the first battle—nor, for that matter, did all the soldiers. Corporal Selden Day of the 7th Ohio Infantry remembered exchanging shots with Confederate troops at the Battle of Kernstown in 1862. As his unit stood in an open field blazing away at the enemy crouched behind a stone wall, Day found himself alongside an unnamed comrade. “He was firing away as fast as he could,” said Day. “I looked at him as he was loading his gun and preparing for another shot, when he said to me, ‘Isn’t it fun!’ I did not reply, and when I looked at him next he was dead.”

The Virginia Military Academy cadets who helped turn the tide at the Battle of New Market in 1864 were the most famous of the boy soldiers, but they were hardly the only Southern schoolboys to fight together as a unit. The Richmond Howitzers fought in the first battle of the war at Big Bethel, Virginia, in June 1861, while cadets from the Citadel in Charleston, South Carolina, and West Florida Seminary in Tallahassee, also saw service during the war.

Most young soldiers enlisted individually, often as drummer boys, buglers, couriers, and surgeon’s aides. The most famous of all drummer boys—indeed, the most famous boy soldier of the war—was Ohio-born Johnny Clem, who went off to war in 1862 at the age of 10. At Chickamauga, one year later, Clem swapped his drum for a sawed-off musket and rode into battle atop an artillery caisson. At the last-ditch stand on Snodgrass Hill, Clem supposedly shot down a Confederate colonel who had called on the “little fellow” to surrender. He was promoted to sergeant on the spot. Clem parlayed his newfound fame as “the Drummer Boy of Chickamauga” into a 50-year career in the United States Army, retiring as a major general in 1915—the last actively serving veteran of the Civil War.

Most of the boys, long since grown into men, returned from the war with considerably less fanfare than Johnny Clem. Almost all were proud of their military service; in the words of the Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., himself a veteran, they had been “touched by fire.” By then, too, most had long since gotten over their initial burst of youthful enthusiasm. As Herman Melville also wrote, “What like a bullet can undeceive!”

-Roy Morris Jr.

Let’s not forget Galusha Pennypacker. He became a brigadier general of volunteers at the age of 20, then a brevet major general of volunteers at 21. Stayed in the Army after the war, becoming a full colonel in the Regular Army at 22, in 1866, then a year or so later a brevet major general in the Regular Army in 1867. Retired as a full colonel at the age of 39 due to health issues from wounds suffered during the Civil War.

This is why politicians should be made to fight the wars they start.

Wars are easier to start than stop. People with families are too busy to fight.

Help me stop war,

Which dehumanizes people.

Tears our bodies and minds

With wounds that never heal.

And uses resources we need for families.

Governments can make other choices.