By Joshua Shepherd

“It was a sad, sorrowful day,” recalled Confederate Major James McCreary, “and more tears of grief rolled over my weather beaten cheeks on this mournful occasion than have before for years.” It was no slight observation for McCreary, whose regiment, the 11th Kentucky Cavalry, had seen considerable hard service since the outbreak of the Civil War. But after witnessing the severe mauling of his men at Tebbs Bend, Kentucky, McCreary was left with an inexplicable premonition of ill fortune in the aftermath of the fight. “The commencement of this raid,” he recorded in his diary, “is ominous.”

John Hunt Morgan: “Thunderbolt of the Confederacy”

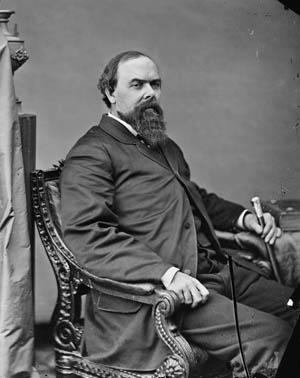

The raid on which the 11th was embarked would become the stuff of American military legend. It was the brainchild of the regiment’s divisional commander, Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan, a transplanted Kentuckian who combined an ease in the saddle with the most necessary trait of a successful cavalry leader—supreme self-confidence. The dashing Morgan’s reputed fondness for women was exceeded only by his love for fighting. A juvenile argument at Lexington’s Transylvania University had led to a duel and expulsion in 1844, and Morgan experienced a dose of real fighting three years later when he served as a lieutenant in the 1st Kentucky Cavalry during the Mexican War, seeing action at the hard-fought and narrowly won American victory at Buena Vista.

His brief taste of soldiering virtually ensured that Morgan would don a uniform when the secession crisis resulted in the outbreak of Civil War. Although by no means an advocate of Southern independence, Morgan raised and trained a volunteer company, the Lexington Rifles, in 1857. When Kentucky neutrality proved elusive, he unflinchingly cast his lot with the Confederacy, and in September 1861 he led his men south to link up with other Confederate forces. The following April, Morgan was named colonel of the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry.

Morgan quickly proved himself adept at irregular operations, menacing enemy supply depots and lines of communication in hard-driving raids that left befuddled Federal commanders wobbling on their heels. In July 1862, he led a raid deep into his home state and captured some 1,500 Federal troops. His most spectacular coup came that December, when he led a combined arms force of about 1,300 men in an unexpected strike against an enemy brigade guarding the Huntsville crossing of the Cumberland River. Despite being up against some 2,400 Federals, Morgan fixed his opponent with infantry, lashed his flanks and rear with cavalry, and made off with more than 1,800 prisoners. Awarded a brigadier’s star for the stunning exploit and heralded a partisan genius in the Southern press, Morgan earned the sobriquet of “Thunderbolt of the Confederacy.”

Unfortunately, Morgan’s own commanding officer was not as effusive in his praise. Braxton Bragg, arguably the most despised general in the Confederacy, grudgingly admitted that Morgan had few peers as a partisan leader but regarded him and his troops as gravely deficient for conventional cavalry operations. Eminently fussy by nature, Bragg was easily nettled by Morgan’s swaggering troopers, self-styled knights in gray who were ill disposed to submit to regular military discipline. Bragg’s subordinates generally responded with a seething contempt for their commander’s abilities, or lack thereof, and such near insubordination proved particularly acute among commissioned officers hailing from the Bluegrass State. Bragg’s cool personality and inept generalship, thought one of Morgan’s men, “have made an abhorrence of him part of a Kentuckian’s creed.” Ultimately, Bragg was left distrustful of his hell-for-leather horsemen, and he would later write that Morgan, despite his undeniable skills, was “a dangerous man, on account of his intense desire to act independently.”

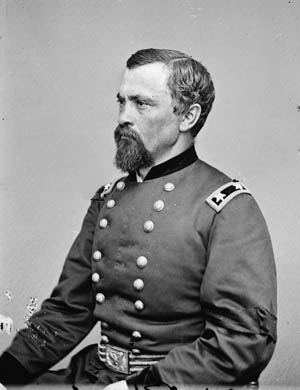

Morgan’s Ambitious Plan

By the summer of 1863, Bragg would be in desperate need of a cavalryman with just such a predilection for independent command. The Army of Tennessee’s senior officers expected to receive a multi-pronged Union thrust into Middle and East Tennessee. The Federal Army of the Cumberland under Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans was within striking distance of Bragg, whose army occupied the Duck River line centered at Tullahoma. Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside was likewise known to be mustering the Army of the Ohio, estimated between 15,000 and 30,000 men, for a push into East Tennessee. Centered in Glasgow, Kentucky, was a formidable detachment of Federal cavalry, thought to be upward of 5,000 men, under the command of Brig. Gen. Henry Judah. It was feared that as Rosecrans and Burnside advanced Judah would maintain communication between the two Federal forces and be in an advantageous position to fall on Bragg’s flanks and rear should the latter be forced to give ground.

Bragg opted to assume the strategic defensive and give up the Tullahoma line, fall back behind the Tennessee River, and then turn to fight Rosecrans somewhere in the vicinity of Chattanooga. To render the delicate maneuver of withdrawing in the face of the enemy less hazardous, Bragg was considering a plan suggested by Morgan. As usual, the cavalryman thought on a large scale. He proposed to lead his entire division, nearly 2,700 men, on a massive raid far into the Federal rear to wreak havoc on Rosecrans’ lines of communication, threaten Louisville, and give Bragg a better chance of withdrawing his army from Tullahoma unmolested. Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, Bragg’s chief of cavalry, had suggested a similar feint toward Louisville as early as March, and he eagerly endorsed Morgan’s plan.

Defying Bragg’s Orders

Fully aware of Morgan’s penchant for recklessness, Bragg approved the operation but outlined rigid parameters designed to keep his impetuous partisan commander in check. On June 14, Wheeler forwarded written authorization for the raid. Morgan would be allowed to take just 1,500 men; the balance of his division would remain behind to screen Bragg. Furthermore, Wheeler stressed that the operation was designed to relieve pressure on the Army of Tennessee, and Morgan should remain close enough to his base to directly cooperate with Bragg. “Should you hear that the enemy is advancing for a general engagement,” wrote Wheeler, “General Bragg wishes you to turn rapidly and fall on his rear.” And despite Louisville’s tantalizing proximity to the Union-loving heartland of Indiana, the raiders were to confine their movements to Kentucky.

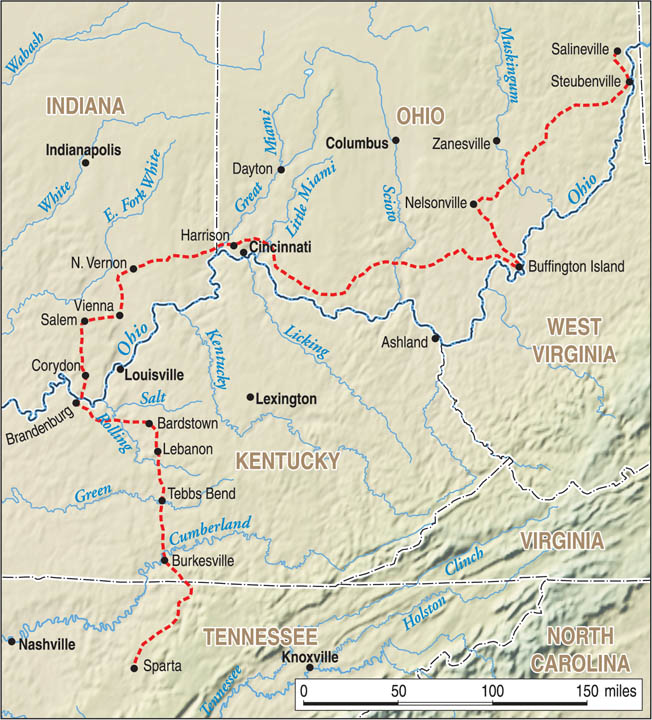

Not surprisingly, Morgan had plans of his own. In a meeting with his senior officers, he revealed the ambitious scope of the proposed expedition, which he had clearly been contemplating for some time. Morgan intended to take the bulk of his division on an unprecedented raid through Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio before returning to Confederate lines by way of West Virginia. Morgan’s officers, who were by no means strangers to desperate operations behind enemy lines, were nonetheless left speechless by the general’s plan. Morgan was confident they could outpace any Federal pursuit but highlighted four primary obstacles to the success of the raid: crossing the Cumberland River, crossing the Ohio River, bypassing Cincinnati, and recrossing the Ohio. “All who heard him felt he was right in the main,” recalled one officer, “although some of us were filled with a grave apprehension.”

Morgan did not inform his officers of Bragg’s explicit orders to limit the raid to Kentucky. But in a private conversation with Colonel Basil Duke, his senior brigade commander, brother-in-law, and closest confidant, Morgan made a stunning admission. “General Morgan told me,” Duke later recalled, “that General Bragg had ordered him to operate in Kentucky, and further stated that he intended, notwithstanding his orders, to cross the Ohio.” Morgan feared that if he followed the letter of his instructions and remained in a state teeming with Federal troops the contest “would be decided very soon, and he would be driven out or cut to pieces in a few days.”

Entering Indiana presented greater prospects for success. Morgan was certain that such an unexpected move would draw thousands of pursing Federals out of Kentucky, where he could keep them occupied for weeks on end. From a strategic standpoint, Morgan felt that the Federals would do better to focus their energies on Bragg, but he was equally certain that the mass hysteria that resulted from an invasion of the North would compel the Union high command to deal with the threat immediately and “furnish the troops that would be called for.” Morgan was willing to run the very real risk of wrecking his division, as well as his own career, flatly stating that “even if he lost his command, he could greatly benefit General Bragg by crossing the Ohio River, and only in that way.” Notwithstanding such high talk, it was evident that Morgan conflated genuine patriotism with unbounded ambition. Crossing the Ohio with a substantial number of troops, observed Duke, “had long been a favorite idea” of his exuberant brother-in-law.

Crossing the Cumberland River

As he began to implement the operation, Morgan ordered Duke to dispatch horsemen to scout a number of potential fords along the Ohio River upstream from Cincinnati. Another body of 62 men led by Captain Thomas Hines moved out under the vague pretense of operating “north of the Cumberland” but headed straight for Indiana. Anticipating his orders, Morgan had already set his troops in motion by June 11, heading out from Alexandria, Tennessee, on what proved to be a fitful start to the raid. A hesitant Bragg immediately recalled Morgan’s troopers to counter the Federal cavalry brigade of Colonel William Sanders, whom he feared was targeting East Tennessee for a raid of his own. The threat proved to be groundless, but Morgan was delayed for the better part of two weeks.

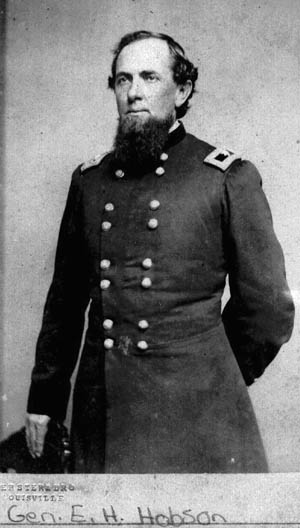

By June 30, Union pickets on the Cumberland River were growing suspicious of an increased Confederate presence on the south bank of the river. The Federal commander in the area, Brig. Gen. Edward Hobson, was convinced that Morgan’s troops had occupied Turkey Neck Bend in force and threatened a crossing. A competent horse soldier and veteran of the Mexican War, Hobson requested permission to attack Turkey Neck Bend that night and post a cavalry brigade at Burkesville, Kentucky. His immediate commander, Henry Judah, demurred, regarding an enemy crossing of the swollen Cumberland as extremely unlikely. Hobson sent a single company to Burkesville.

Judah’s tepid response would prove to be a serious mistake. On the evening of June 30, Colonel Richard Morgan’s 14th Kentucky Cavalry began crossing the river to secure a bridgehead on the north bank. Although ultimately authorized to lead 2,000 men north, Morgan had characteristically ignored his orders, leaving behind a single regiment, the 9th Kentucky, to operate with the Army of Tennessee. Morgan would mount the long-awaited raid with the lion’s share of his division, consisting of two brigades of crack Confederate cavalry. His second brigade, consisting of about 1,000 men commanded by Colonel Adam “Stovepipe” Johnson, began crossing the Cumberland on the morning of July 1. They were followed by his first brigade, about 1,500 men, led by Basil Duke. Morgan’s complement of artillery consisted of Captain Edward Byrne’s Kentucky Battery, which boasted 12-pounder howitzers as well as several Parrott rifles.

By July 2, Morgan had all his men across the river and handily brushed aside the company that Hobson had posted at Burkesville. Rosecrans and Burnside were informed of developments that afternoon, and Hobson, desperate to slow the advance of Morgan’s troops until an effective response could be mounted, ordered reinforcements to the vicinity. Inexplicably, the order was countermanded by Judah.

“The Fourth of July is a Bad Day to Talk About Surrender”

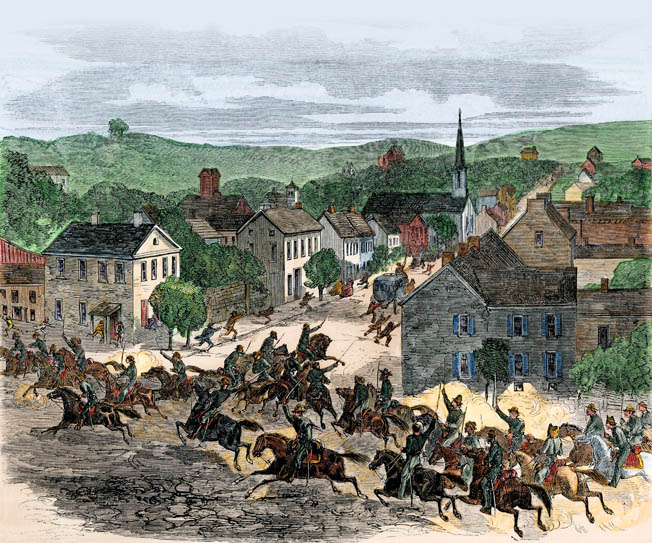

Morgan’s division was already riding hard to the north. On the afternoon of July 3, the horsemen thundered into Columbia, Kentucky, driving off 100 enemy cavalry in a brief skirmish. From the outset of the raid, Morgan’s men took considerable liberties with private property, a dangerous breach of discipline bemoaned (at least formally) by the officers. In the aftermath of the fight, some of the troopers, reportedly in their cups, broke into one of the town’s stores and commenced looting. Lt. Col. Robert Alston, Morgan’s chief of staff, angrily ordered the return of the goods, observing: “These outrages are very disgraceful, and are usually perpetrated by men accompanying the army simply for plunder. They are not worth a damn, and are a disgrace to both armies.”

That evening the main body camped about six miles north of Columbia, and during the night Morgan’s scouts reported hearing the disconcerting sound of Federal troops feverishly felling trees. By dawn, Morgan found himself facing a difficult decision. Drawn up on Tebbs Bend of the Green River were Federal troops who clearly intended to fight—men from the 25th Michigan, bolstered by companies from the 8th Michigan and 79th New York. The thin force, around 200 men, was commanded by Colonel Orlando Moore, a starchy veteran officer of the 6th U.S. Infantry who clearly knew his business. Moore used the ground to good advantage, deploying his men on the Columbia-Campbellsville Turnpike where the road bottlenecked across a high ridge before dropping down to a bridge over the Green River.

Moore had further strengthened his position with crude but effective field works. Out front was a simple rifle pit manned by 75 men. The bulk of the force occupied a more formidable earthwork whose front was covered by a nasty tangle of abatis. Morgan, inherently aggressive and disinclined to seek a detour, opted to assault the position. A detachment of Confederate horsemen was ordered to cross the river and fall on the bridge from the rear, while the main body advanced along the turnpike. At about 6:30 am, a salvo from Byrne’s Parrotts announced the Confederate presence, and Morgan sent in a demand for unconditional surrender. “If it was any other day,” Moore responded, “I might consider your demand, but the Fourth of July is a bad day to talk about surrender, and I must therefore decline.”

Moore Defies Morgan’s Advance

Moore’s rejection brought on the fight in earnest. Morgan sent in elements of Stovepipe Johnson’s brigade, the 11th and 7th Kentucky with a single company of the 10th on the right. Advancing dismounted, Johnson’s men seized the enemy’s advanced line, where they were afforded a better view of Moore’s main position. Morgan and Johnson entered the rifle pit for a better look, and Johnson blanched at the sight. Moore had clearly laid a deadly trap for the Southerners, and Johnson pleaded in vain to bypass the position and locate alternate crossings of the Green. “I begged the general not to attempt it,” he recalled, “as I had but seven rounds of ammunition and we could easily flank the place; but he insisted and I led my men to the charge.”

Johnson’s opinions should have carried greater weight. A native of Kentucky, he moved to the Texas frontier in 1854 and cut his teeth fighting the much dreaded Comanche. Regarded as an expert tracker and scout, he served in that capacity early in the war with no less a fighter than Nathan Bedford Forrest. He then raised the 10th Kentucky Cavalry and led his men on the first Confederate incursion into Indiana in July 1862. It was during his celebrated raid of Newburgh that Johnson earned the nickname “Stovepipe” when he bluffed a garrison of rattled Hoosiers into surrender after rolling a preposterous Quaker gun into view. His men loved him for the exploit.

Johnson led his brigade forward supported by the 5th Kentucky of Duke’s brigade. Despite a weight in numbers, the Confederates were unable to gain the earthwork and were subjected to heavy fire as they stalled in the confusing mass of downed timber in front of the Federal position. At times the combatants fought from the mere distance of six feet. In an attempt to flank the position, Colonel David Chenault’s 11th Kentucky was ordered to turn the enemy’s left. Chenault gamely led his men into the abatis but was fatally shot through the head as he fired his sidearm into the earthwork.

Further attempts to force the bridge were deemed pointless, and Morgan pulled his men out, bypassed Moore’s position by means of alternate fords, and picked up the turnpike again north of the Green River. The furious fight at Tebbs Bend had cost Morgan 35 killed and 45 wounded. Writing in his diary that evening, Alston recorded that the men remained in good spirits but were growing fatigued after enduring “bad roads, little rest or sleep, little to eat, and a fight every day.” Morgan, he thought, looked “haggard and weary.”

The Death of Morgan’s Brother

The following day was only worse. Morgan rode hard for Lebanon, hoping to bag the town’s rich Federal supply depot. The Union officer in charge at Lebanon was Lt. Col. Charles Hanson, an acquaintance of the Morgan family, who led his own 20th Kentucky as well as detachments from three other regiments—all told about 380 men. Burnside had telegraphed Hanson the previous evening with orders to hold the town until reinforcements arrived. When Morgan’s division converged on the town early that morning, Hanson was driven through the streets to a ready-made fortress he had prepared in advance consisting of the depot of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad and several adjacent structures. Morgan demanded unconditional surrender. The Federals refused, and he shelled the depot until its upper story was reduced to rubble.

Around 1 pm, after nearly seven hours of frustrating stalemate, Morgan ordered the 2nd and 5th Kentucky to dismount and storm the buildings. As the troops rushed forward, the general’s youngest brother, Lieutenant Thomas Morgan, was shot in the chest and exclaimed, “Brother Cally, they have killed me!” The attack fell apart, but the death of Tommy Morgan, something of a favorite in the division, incited “a terrible excitement” thought Colonel Alston, and the men were reduced to “a state of frenzy.” Morgan ordered the buildings around the depot burned, and angry troopers yelled that they would burn the entire town. In the face of such threats, Hanson capitulated at 1:20 pm.

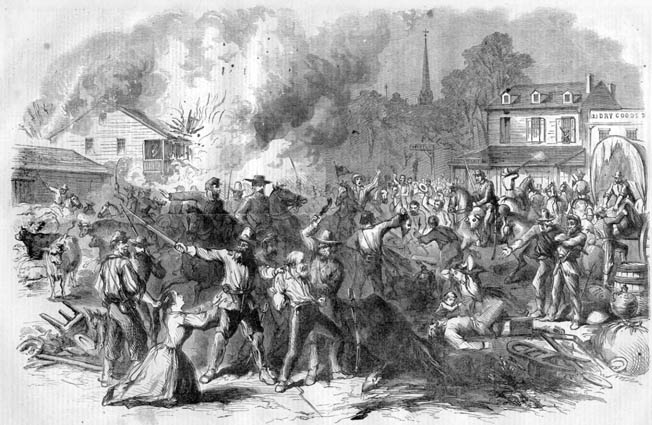

In the wake of the surrender, the general nearly lost control of his enraged men. Captain Charleton Morgan stalked up to Hanson, grabbed him by the beard, and raged, “I’ll blow your brains out, you damned rascal!” Confederate Colonel D. Howard Smith, who had been reared with Hanson, intervened, and General Morgan reportedly drew his pistol to restore order. No further blood was shed, but the Confederates made a swift wreck of the town. About 20 buildings were destroyed and one disgusted officer recorded that a minority of unsavory soldiers “behaved badly breaking open stores and plundering indiscriminately.” All in all, the repeated robbery of Kentucky civilians, whom the Confederates had ostensibly come to liberate, was “very disgraceful.”

Delaying the Raiders

The breakneck pace of the raid was clearly taking a toll on the exhausted cavalrymen, but Morgan could ill afford to rest his men after expending so much time and energy dealing with small but stubborn detachments of Federal troops. He met with the same difficulty when he arrived at Bardstown at 4 am on July 6. The night before, his lead elements had collided with 25 men of the 4th U.S. Cavalry, who promptly took refuge in a livery stable and barricaded the doors with lumber and horse manure. A dismounted assault failed to dislodge them, as did an attempt to set fire to the building, and the stubborn defenders refused two demands to surrender, holding out until 7 am, when Confederate artillery was unlimbered and trained on the building. Dick Morgan, exasperated at the embarrassing episode and seething over the death of his brother the day before, initially refused to recognize the white flag but soon thought better of it and accepted the surrender. A mere two dozen defenders had detained Morgan’s division for several more precious hours.

Morgan could ill afford such delays. The day before, Burnside had placed Hobson in command of a provisional cavalry division of nearly 4,000 men, which set out in pursuit from Greensburg, Kentucky. Morgan had a head start on his opponent, but Hobson, a solid officer and dependable commander, could read a map. By the afternoon of July 7, he was convinced that Morgan was heading for Brandenburg, Kentucky, which sat on the Ohio River about 50 miles downstream from Louisville. From Brandenburg, Morgan’s next move was obvious.

He had, in fact, already set in motion his plans for a river crossing. On the afternoon of July 7, Morgan dispatched Captain William Davis and a company of cavalry to ride beyond Louisville and cross the river east of town, where it was hoped they would divert attention from the main body. Another detachment rode into Brandenburg for a linkup with the mercurial Captain Thomas Hines, who had led a brief raid into southern Indiana. Hines had tangled with particularly feisty Hoosier militia and gotten the worst of it. Of the 80 men who had followed him, only 12 escaped.

Pressing Onward to Brandenburg

For Morgan, there was no turning back. His division reached Brandenburg in force on the morning of July 8 and immediately made preparations for a crossing of the Ohio. Two steamers, John T. McCoombs and Alice Dean, were already available, having been seized the previous day by members of the 10th Kentucky. But as a heavy morning fog lifted from the river, it became apparent that the crossing would be contested. About 130 Indiana militia under the command of Colonel John Timberlake had hastily assembled at Morvin’s Landing on the north bank of the river, training a single 6-pounder at Brandenburg.

As soon as the fog lifted, Timberlake’s gun dispersed Morgan’s men from the Brandenburg wharf, and he confidently shouted across the river for the surrender of the two steamers, or “I will blow you all to hell in five minutes.” One cheerful Confederate trooper, with perhaps more good humor than good sense, shouted back, “Oh hell, old man, come over and take a drink.” The exchange that resulted was less than cordial. Morgan’s guns went into battery on Brandenburg’s courthouse hill and promptly scattered the Hoosiers, who scampered back into the bushes from the river bank.

With Morvin’s Landing cleared, Morgan began crossing his men and secured a bridgehead with the 9th Tennessee and 2nd Kentucky. As soon as the two regiments were over, Morgan was delayed again by the abrupt appearance of the Federal gunboat USS Springfield, which commenced a duel with the raiders’ guns at Brandenburg. With Hobson’s force fast closing the distance to his rear, Morgan grew concerned that the Union gunboat could effectively cut him off from the two regiments on the north bank of the river. His fears were unfounded. Ensign Joseph Watson, Springfield’s commander, drew off for reinforcements after a noisy but bloodless artillery exchange. He later reported that the raiders numbered at a greatly exaggerated 10,000 men.

Morgan resumed ferrying his troops. Duke’s brigade went over soon after dark, and Johnson’s brigade continued crossing until after midnight. Alice Dean was burned to the water line, but McCoombs, whose skipper was an old acquaintance of Colonel Duke, was spared. Not long after Morgan’s rear guard disappeared from the river bottoms early the next morning, Hobson’s provisional division, which had stopped to rest a mere dozen miles away, finally arrived in Brandenburg.

A 30 Minute Fight

As Morgan drove north up the Mauckport Road, the local militia was scrambling to halt the invasion. By the morning of July 9, about 450 Home Guards under the command of Colonel Lewis Jordan took up position on a slight ridge about a mile south of Corydon and hastily improvised breastworks from logs and fence rails. At half past noon, Morgan deployed his division, Johnson’s brigade out front with Duke in support. The battle was joined on the Confederate right, where Dick Morgan’s 14th Kentucky engaged in a sharp fight with the militia to their front, who put up stiffer resistance than expected. The guardsmen repulsed three separate charges, and Duke recalled with grudging admiration that the Hoosiers “resolutely defended their rail piles.”

Real fighting, however, lasted no longer than 30 minutes. The militia line crumpled when Johnson’s dismounted troopers snapped at the flanks, and as the Hoosiers raced pell-mell for Corydon, the battle degenerated, recalled one survivor, into “a series of skirmishes in which each man seemed to fight upon his own hook.” Morgan was determined to capture the lot. Byrne’s artillery unlimbered on the heights above Corydon, and the 14th Kentucky galloped east of town, where the troopers seized the Louisville Plank Road, the Hoosiers’ only adequate route of retreat or reinforcement. Jordan quickly surrendered, and Morgan just as quickly paroled the militia en masse. The Confederates briefly rested in town, tramping into private homes in a search for food and ransacking Denbo’s Store, where they made off with boots, hats, and clothing. Morgan refrained from burning the town’s mills after demanding payment of $3,000. He settled for $2,100.

The Union Panic

The furor created by the invasion of Indiana was exactly what Morgan hoped. Every militia company south of the National Road was mobilized, and Oliver Morton, the state’s iron-fisted Republican governor, flew into a state of near panic. Morgan contributed to the confusion by unleashing a lively campaign of false intelligence, the handiwork of George “Lightning” Ellsworth, a popeyed eccentric who possessed boundless energy for disrupting the Union war effort. Regarded as little more than a buffoon by some of Morgan’s officers, Ellsworth was unquestionably skilled at tapping telegraph lines and copying the rhythm of Federal operators. Thanks to his efforts, the Union lines were flooded with false reports of Morgan’s whereabouts and intentions; nearly every town in southern Indiana considered itself specifically targeted.

Despite the hysteria, Morgan was anxious to get out of the state as quickly as possible after causing as much damage as possible in the process. His main body, as well as smaller parties dispersed in the countryside, stripped the region of horses, impressing fresh mounts multiple times each day. The division averaged 21 hours in the saddle and 40 miles per day, and even the best horses gave out after 20 miles. The raiders gleefully wrecked the state’s infrastructure, destroying bridges, rail lines, depots, and mills in a wide swath across southeast Indiana.

After scattering 200 jittery militia at Salem on July 10, Morgan’s feats created a sensation in the Northern press. He ordered a number of bridges burned, as well as the town’s railroad depot. In the process, his men lost all sense of proportion. Duke thought the ever present danger had rendered the troops more and more reckless, resulting in wholesale plunder of the town’s stores. “It seemed to be a mania,” said Duke, “senseless and purposeless,” as men seized such useless articles as bolts of cloth, birdcages, and ice skates. “They pillaged like boys robbing an orchard,” he recalled, adding that he was shocked “that such a passion could have been developed so ludicrously among any body of civilized men.”

“The Darkest of All Nights”

As soon as the merriment at Salem was over, Morgan had the division on the move—and for good reason. Hobson was hot on his trail and arrived in Salem at 9 o’clock that evening. Morgan drove his men hard, reaching Vernon on the Muscatatuck River the next afternoon. A scratch force of about 1,000 militiamen occupied impressive bluffs on the north bank and twice refused a Confederate demand for surrender. Morgan was bluffing. After dark, the militia heard what was thought to be a crossing and rushed to counter the threat; several men lost their footing and tumbled down the bluffs only to find that a local farmer’s cows had caused the commotion.

By then the raiders were gone. Disinclined to waste further time on militia, Morgan pulled out and slipped away on back roads. The division made for the hamlet of Dupont, where the raiders caught about four hours of sleep and then were treated to a Sunday dinner of 2,000 hams liberated from a local packing house. By the morning of July 13, Morgan was closing fast on the Ohio border and facing what he considered the greatest obstacle of the raid, the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton Railroad. Not without good reason, Morgan feared that Burnside, who had upward of 10,000 armed men in Cincinnati, could easily avail himself of the rail line to rapidly deploy troops across Morgan’s front.

That Morgan was able to cross the CH&D and bypass a heavily defended Cincinnati unmolested was nothing short of miraculous. His plan, which was to cross the railroad at night and keep moving until he was well east of Cincinnati, resulted in a merciless ride that taxed man and beast. “It was without doubt the darkest of all nights,” remembered Lieutenant Kelion Peddicord of the 14th Kentucky. The men were spent. “Oftentimes I have seen on that raid both man and horse,” Peddicord wrote, “nodding together, and at such times the horse staggering like one intoxicated.” To Duke, the ride around Cincinnati was nothing short of a nightmare.

Avoiding Union Gunboats

Upon reaching Sharonville, 17 miles northeast of Cincinnati, Morgan felt confident enough to celebrate with his officers over brandy and cigars. Meanwhile, his exhausted and hungry men spread out to forage what they could from the nearby countryside. When they found a local intersection defended by a mere 200 convalescents and militia, Morgan chose to backtrack to an alternate route rather than throw his exhausted men into more unnecessary combat. At 4 pm on July 14, the division set up camp at Williamsburg, Ohio, having ridden a remarkable 84 miles in 36 hours.

At 3:30 the next morning, they were back in the saddle again. Although Morgan had succeeded in wreaking havoc on a wide swath of Indiana and Ohio, the raid was taking a considerable toll on the division, and he knew it. Of the 2,460 men who headed out on the raid, only 2,000 were left in the ranks. Despite the continued destruction of bridges and rail lines, Morgan’s paramount objective was to get his men back across the Ohio River. He sent Dick Morgan to investigate possible crossing sites, and Dick found the ford at Ripley defended by militia and a single gun. He didn’t press for a closer look, but he did glimpse a most unwelcome sight: Federal gunboats in the river.

The presence of such vessels, which could tear his command to pieces during a river crossing, forced Morgan to continue east to the fords above Portsmouth, where, in the summer months, gunboats typically found the shallow waters of the Ohio unnavigable. The Ohio couldn’t be crossed too soon. On the evening of July 14, a persistent Hobson had reached Mulberry, Ohio, 14 miles behind Morgan, where he linked up with an additional brigade of Michigan cavalry under the command of Colonel William Sanders.

As the Confederate column drove deeper into Ohio, it was regularly delayed by roadblocks of felled trees, testament to industrious northern farmers more adept with an ax than a gun. Local militias were not averse to fighting and increasingly snapped at the raiders’ flanks as they passed, inflicting casualties by twos and threes. Duke respected the militias’ grit but noted that larger bodies were easily put to flight by simple flanking maneuvers. “We captured hundreds of prisoners,” noted McCreary in his diary, “but, parole being null, we can only sweep them as chaff out of the way.”

“All Our Troubles Are Now Over”

On July 17, the raiders tangled with a substantial force of 1,500 militia at Berlin Crossroads, and although they were eventually driven off Morgan lost three more precious hours in the process. By the time he approached the roads to the ford at Eight Mile Island, near Cheshire, Morgan found the rugged hills commanding the route swarming with militia. The general, along with Duke, caught a glimpse far more ominous: telltale plumes of smoke from Federal gunboats. The pair agreed to make for the ford at Buffington Island, where the river was expected to be entirely impassable to larger vessels. To get there, the division was forced to utilize the Stagecoach Road, a narrow thoroughfare that paralleled the Ohio but was flanked by steep hillsides guarded not by militia but two regiments of veteran Federal troops under the command of Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes, whose stubborn delaying action cost Morgan three killed and 16 wounded and afforded the pursuing Union cavalry time to close the distance on the Confederate rear.

The raiders arrived in Cheshire at 1 pm. Morgan was elated. Sitting on the front porch of a general store, he called to Stovepipe Johnson to rest with him a bit. The general was smiling and clearly relieved. “All our troubles are now over,” he told his brigade commander. “The river is only twenty-five miles away, and tomorrow we will be on southern soil.” Unknown to Morgan, the Federal noose was tightening around his division. Hobson arrived in Cheshire about 8 that evening, briefly rested, and then rode on after the raiders. Judah, who reached Pomeroy at 4 that afternoon, decided on a forced march for Racine, a crossroads hamlet within striking distance of Buffington Island. Heavy rains had unseasonably swollen the Ohio, and some of the water at Buffington Island, normally around three feet deep in July, now was double that depth.

Disaster at Buffington Island

Morgan rode into Portland Bottoms, a large flood plain adjacent to Buffington Island, at around 8 pm. In the dark, his scouts located a redoubt guarding the ford, defended by what appeared to be Federal troops and two guns. After assessing the situation, Duke pressed for immediate action, suggesting that the division abandon their wounded, seize the redoubt in a night attack, and swim their horses to West Virginia. Morgan mulled over his choices and decided a night crossing was too risky; he would assault the earthwork and cross his rested men in the morning. Even men in the ranks were uneasy about the decision. “All night long every one of us that I heard express themselves,” remembered Private John Weatherred, “said we would be captured, many of us, if we remained all night.”

The river was blanketed by heavy fog the following morning, July 19. Duke advanced the 5th and 6th Kentucky to attack the redoubt but found it abandoned. The jittery militiamen guarding it had run off in the night. About 110 men of the 9th Tennessee nabbed a flatboat and four skiffs, crossed the river, and took up positions on the south bank to cover the rest of the division as it came over. Federal cavalry was known to be near, but so far all was going according to plan.

Suddenly, at 5:30 am, bedlam erupted. Elements of Duke’s brigade patrolling in dense fog south of Portland Bottoms ran into Judah’s advance guard, which had executed a forced night march, opening a sharp skirmish that left the Federals reeling. Thirty Union troops were captured, and Judah himself narrowly escaped. Duke’s horsemen gave chase through a thinning fog but saw the enemy’s main body deploying into line of battle. Judah had about 1,000 men and three batteries in his scratch brigade.

Duke hastily formed his troops across the bottoms to cover the rest of the division but was badly outmatched. Judah’s batteries possessed 3-inch ordnance rifles that played havoc on the raiders’ line, and a wild charge of the 5th Indiana Cavalry cut up Duke’s right rear, seizing several guns. Looking to the river, Duke was horrified. A Federal gunboat, USS Moose, accompanied by two armed steamers, appeared off his flank and unleashed a devastating enfilade fire. Duke’s line crumpled under the pressure, but he succeeded in withdrawing his men in good order, reforming them closer to Johnson’s brigade, which was positioned along the Chester Road.

Momentum was clearly against the cornered raiders. Union Colonel August Kautz, whose fresh troopers had been sent out by Hobson to ride down Morgan’s command, drove into Confederate pickets two miles west of Buffington and then assaulted Johnson’s right. Morgan held his own until 6:30, when more Federal troops poured into the fight—Sanders’ brigade along with the 11th Michigan Battery. One gun unlimbered on the Chester Road, within 600 yards of Johnson, while another opened fire from a commanding hill that covered the bottoms. Great gaps were torn into the ranks of the disoriented Confederates, who broke in panic for the rear. The raiders, remembered Private Alfred Austin of the 5th Indiana, “skedaddled like a scared flock of sheep.”

In the confusion, Morgan was able to make off with about half the division while Johnson and Duke covered the retreat with what men they could gather. The two brigade commanders hastily conferred. Duke offered to fight it out in the bottoms while Johnson extricated the remnants of his brigade. Duke could muster no more than 200 men, but they held out until their ammunition was expended. A wild race ensued. Morgan’s indomitable brother-in-law, at the head of 50 frightened and hungry men, was captured hiding in nearby woods. The fight at Buffington Island had been an utter disaster. Morgan suffered 57 killed, 63 wounded, and 50 captured. An additional 570 disoriented raiders were rounded up over ensuing days.

The Fate of John Hunt Morgan

Morgan desperately sought to escape with the shattered remnants of his command. The following afternoon, the demoralized Confederates arrived at Belleville Island Ford and immediately attempted a crossing there. While Morgan was midstream, Moose steamed into range, although Lt. Cmdr. Leroy Fitch mercifully ordered his gunners not to fire on the helpless Confederates in the river. About 300 men reached the West Virginia shore. Morgan, seeing the bulk of his command still stranded in Ohio, headed for the north bank.

Miraculously, Morgan kept his scarecrow division on the run for another week. Increasingly hemmed in and daily losing men to capture and desertion, Morgan made a final attempt to reach Bobb’s Island Ford on July 26. On the Beaver Creek Road, he ran into a barricade manned by wide-eyed volunteers of the New Lisbon Militia armed with an antiquated cannon. Most of the militia scattered, but their captured commander, Captain James Burbick, agreed to accept Morgan’s sick and wounded and guide the remaining Rebels to Pennsylvania. A mere 12 miles from the border, Morgan saw a dust cloud on a parallel farm lane and recognized that Federal cavalry had finally cut him off. The game was up. Hoping to cheat his pursuers one last time, Morgan abruptly offered to surrender to Burbick. The startled militia officer agreed, and the men negotiated rather lenient terms, which granted the raiders parole, their side arms, and a safe escort out of Ohio. Morgan then trotted to a nearby farm and calmly sat down in the shade of a cherry tree. Many of his troopers simply collapsed by the side of the road for a few moments of much needed sleep.

Major George Rue, the Federal officer who had finally trapped the elusive Morgan, arrived to disarm the legendary general and his senior officers. When informed of Morgan’s surrender terms, Rue blinked in disbelief. “Who the hell is Burbick?” he barked. Brig. Gen. James Shackelford, who met with Morgan in the orchard and ultimately claimed the honor of capturing him, disavowed the arrangement, calling it with some accuracy “not only absurd and ridiculous, but unfair and illegal.” At 3:20 pm, Shackelford tele-graphed Burnside: “By the blessing of Almighty God, I have succeeded in capturing General John Hunt Morgan.”

The next day, Morgan and his men were taken by special train to Cincinnati, where they were tried, convicted of horse stealing, and sentenced to the Ohio State Penitentiary in Columbus. Four months later, Morgan and six of his officers escaped after tunneling through the cement floor of their ground floor cell and scaling a 25-foot-high wall with a rope made of bed sheets. Three of the men subsequently were recaptured, but Morgan made it safely to Franklin, Tennessee. He would be killed by Union cavalry eight months later in Andrew Johnson’s adopted hometown of Greeneville, Tennessee.

The Mixed Legacy of Morgan’s Ohio Raid

The military value of Morgan’s quixotic raid remains controversial, but the consequences for his selfless troopers were painfully obvious. After an epic ride of nearly 1,000 miles, Morgan surrendered a mere 364 members of his once feared division. Morgan’s cavalier élan, carried to a punishing and costly extreme, had resulted in the near destruction of one of the South’s finest cavalry divisions. By the summer of 1863, such horsemen were nearly irreplaceable in an increasingly beleaguered Confederacy.

In the immediate aftermath of the raid, it quickly became apparent that Morgan’s actions had been next to useless in dulling the Federal advance into southern Tennessee. Rosecrans had implemented his much heralded Tullahoma Campaign on June 24, before Morgan’s division had even crossed the Cumberland. By skillful maneuvers, Rosecrans deftly pried Bragg from the Duck River line and clearly had little to fear from Morgan, who was driving somewhat pointlessly into Kentucky. When it came to direct cooperation with Bragg, Morgan might as well have been on the moon.

Some Confederate officers took a long view of the raid. Basil Duke maintained that the raid had postponed Burnside’s invasion of East Tennessee for weeks and delayed reinforcements to Rosecrans that otherwise would have been available to him at Chickamauga. Federal Colonel John McGowan agreed. “Had Morgan been readily beaten back from Kentucky in a crippled condition,” he said, “Burnside would have met Rosecrans at Chattanooga, the battle of Chickamauga would not have been fought, and the war might have ended sooner.”

It is certainly possible to argue that Morgan’s unauthorized crusade north of the Ohio contributed in some measure to the great battle at Chickamauga. Such reasoning was lost on the petulant Bragg. Unable to discipline the now incarcerated Morgan, the general opted to exact retribution on his helpless troopers. Some 240 of the raid’s survivors were reorganized for service and folded into the cavalry command of Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. Bragg was determined to humiliate Morgan’s men and, in a petty exhibition of juvenile score settling, insisted that their mounts be reallocated. The irascible Forrest would have none of it. A pleased Stovepipe Johnson noted that Forrest risked court martial when he defiantly refused to execute Bragg’s order. “Any man who says that Morgan’s men are not good soldiers and fighters,” claimed Forrest, “tells a damn lie.”

Good fighters or not, Morgan’s expedition was clearly ill advised. Despite its tragic outcome, however, the best appraisal of the raid was offered by Basil Duke. Few veterans of the raid, he thought, ever regretted it. To Confederate soldiers and civilians who had witnessed their homeland ravaged by the horrific scourge of civil war, taking the fight to the enemy’s front door was a luxury “cheap at any price.” It was also a point of honor. “It would have been an inexplicable shame,” wrote Duke, “if, in all the Confederate army, there had been no body of men found to carry the war, however briefly, across the Ohio, and Morgan by this raid saved us, at least, that disgrace.” Perhaps it was enough to justify the cost.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments