By David A. Norris

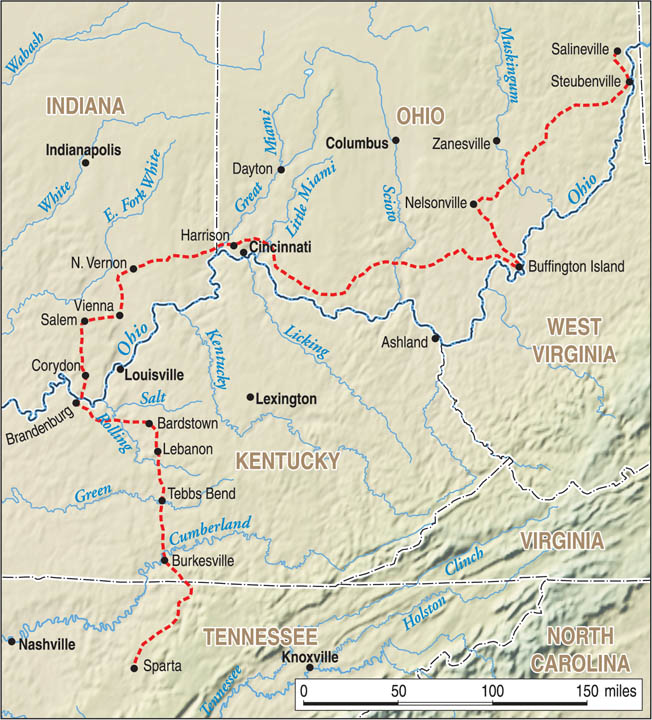

Stepping off of two captured river steamboats, the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry and the 9th Tennessee Cavalry set foot in Indiana on July 8, 1863. On the south bank of the Ohio River awaiting transport were seven more regiments of Confederate cavalry led by Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan. They aimed to keep well ahead of the Union cavalry sent to pursue them and bring the war into Indiana and Ohio, a so far untouched section of the Union. But first they had to get the rest of the army across the river. The slow process of using the captured steamers as ferryboats was about to turn dangerous. One mile above the crossing, dark smoke poured from the stacks of an approaching sidewheel steamer. Then, a plume of whitish smoke gushed from the steamboat’s bow, and cannon shot hurtled toward the Confederates waiting on the Kentucky shore. A gunboat of the U.S. Navy’s Ohio River Division had joined the pursuit of Morgan’s raiders.

In June 1863 Lt. Gen. Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee was at Tullahoma in south-central Tennessee. Facing it was the larger Army of the Cumberland under Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans. A smaller and separate Confederate force under Maj. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner held eastern Tennessee. Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, commander of the Department of the Ohio, pressed against Buckner’s army. Under this dual threat, neither Confederate army could afford to reinforce the other; however, one of Bragg’s generals devised a solution that he thought would swing the initiative back to the Confederates.

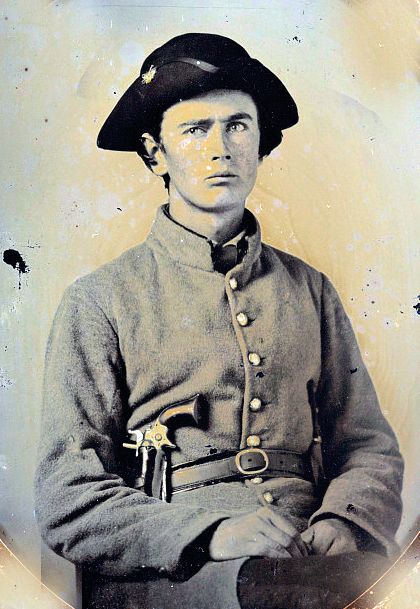

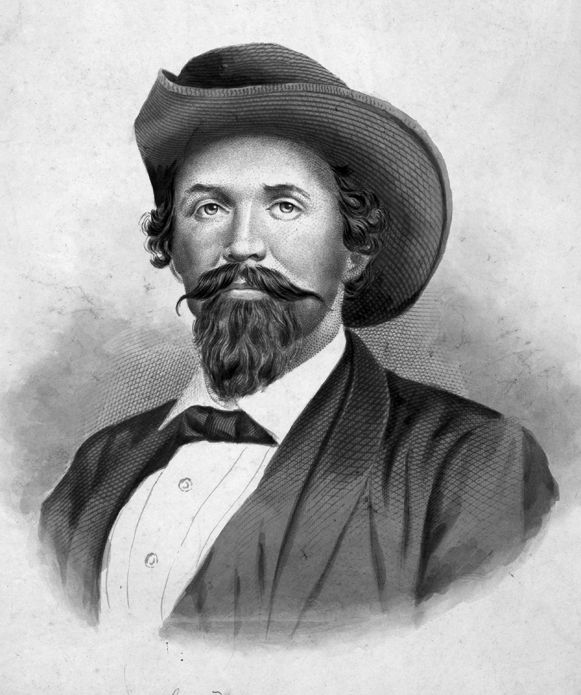

Born in Huntsville, Alabama, Morgan’s family relocated to Lexington, Kentucky, when he was a boy. He served as a private in the U.S. Cavalry during the Mexican War and afterward returned to Lexington where he became a businessman. In September 1861 he led a militia unit known as the Lexington Rifles into Tennesee to join the Confederacy. The following April he raised the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry, of which he became the colonel.

Morgan was a legend among the South’s cavalry commanders. Three times during 1862 he had led long mounted raids from Tennessee into Union-held areas of the border state of Kentucky. At the cost of only light casualties, Morgan’s raiders destroyed millions of dollars’ worth of military supplies, cut railroads, and captured and paroled more than 2,000 prisoners. His successes won him promotion from colonel to brigadier general and a vote of thanks of the Confederate Congress. Beyond their strategic value, his bold raids boosted morale and buoyed hopes for a turnaround in Confederate fortunes west of the Appalachian Mountains.

Morgan’s accomplishments inspired him to suggest to Bragg a raid against Louisville, Kentucky. In Morgan’s thinking, a strike against the great Ohio River port city, with its warehouses and transportation facilities, would distract Rosecrans and ease the pressure on Confederate forces in Tennessee. Morgan estimated that Louisville was defended by only about 300 troops. Such an attack might compel Burnside to detach his cavalry from Buckner and send it to Kentucky for several weeks.

Bragg consented to the new raid. On June 14 Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler confirmed his own meeting with Bragg and informed Morgan that he could have 1,500 men for his expedition. As the commander of Bragg’s cavalry corps, Wheeler was Morgan’s superior.

“I can accomplish everything with 2,000 men and four guns,” said Morgan. “To make the attempt with less might prove disastrous, as large details will be required at Louisville to destroy the transportation, shipping, and government property. Can I go? The results are certain.”

Bragg increased the authorized force to 2,000 men, with the proviso that the raiders hit the Louisville and Nashville Railroad to interrupt Rosecrans’s flow of supplies. Wheeler stressed to Morgan that it was vital that he strike Louisville and return quickly; after all, he was taking a fifth of Bragg’s cavalry.

Although Bragg forbade crossing the Ohio River into the Union states, doing just that was Morgan’s true objective. Three weeks before, Morgan had already sent some “intelligent men to examine the fords of the upper Ohio,” including a crossing from Ohio to West Virginia at Buffington Island.

A separate 25-man detail under Captain Thomas Henry Hines was also on its way north. Disguised as a Union cavalry patrol on the hunt for deserters, Hines’s men crossed the Ohio River on June 18 into Indiana. They searched out Dr. William A. Bowles, a leader of the region’s “Copperheads” (secret secessionist sympathizers in the North), to enlist his help. Bowles informed them that while his adherents had some sympathy for the Confederate cause, that did not extend to their taking the risk of extending any tangible help to an invading force.

For his grand raid, Morgan left Alexandria, Tennessee, on June 11 with 2,460 men. The force was composed of eight regiments of cavalry from Kentucky and one from Tennessee. Morgan had two 3-inch Parrott rifles and two 12-pounder howitzers.

Leading his two brigades were two colonels. Basil Wilson Duke had distinguished himself as commander of the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry, a regiment that Morgan relied upon as his dependable regulars. Duke was Morgan’s brother-in-law.

Morgan’s other brigade commander, Colonel Adam Rankin Johnson, had already crossed the Ohio the previous year. On July 18, 1862, with about 40 men, he captured the town of Newburgh, Indiana. Lacking any artillery, Johnson built a single fake cannon from a pair of wheels and an axle from a wrecked wagon topped with a length of stovepipe. Allowing the garrison to see the gun only at a distance, Johnson convinced them to surrender the town. Thereafter, he was known as “Stovepipe Johnson.”

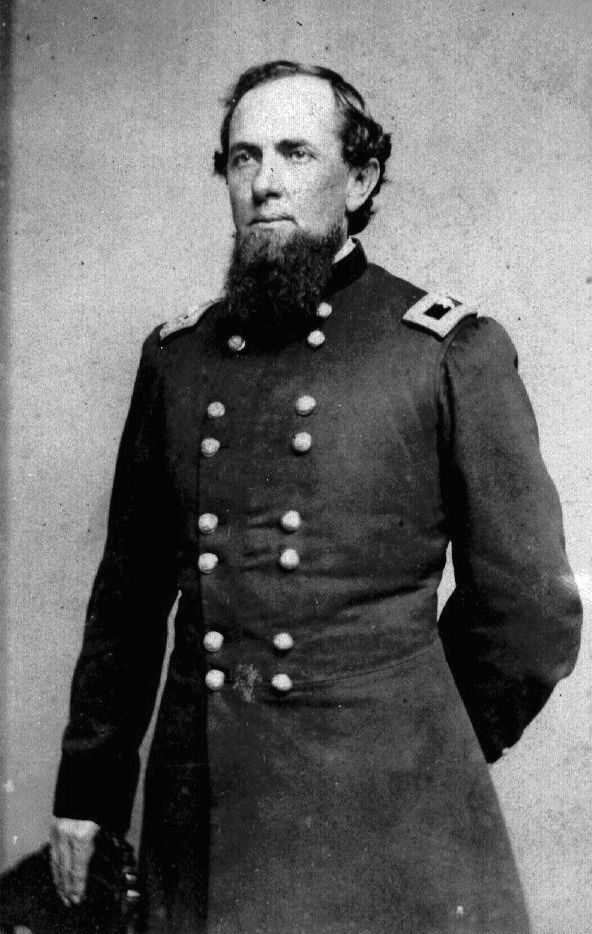

At Glasgow, Kentucky, on June 22, Union Brig. Gen. Henry Judah of the Union XXIII Corps received word that Morgan’s cavalry threatened Carthage, Tennessee. Judah shifted his division to cover the Tennessee border so he could either relieve Carthage or block a potential Confederate advance into Kentucky. Judah’s brigades had been organized as combinations of horse and foot regiments in preparation for Burnside’s intended campaign against Buckner in eastern Tennessee. Another combined brigade consisting of both horse and foot soldiers under Brig. Gen. James M. Shackelford was temporarily placed under Judah’s command. Judah’s move from Glasgow would be the beginning of a month-long odyssey in pursuit of Morgan.

Heavy rains slowed Morgan’s advance to Kentucky. The Obey and Wolf Rivers were so flooded that the Rebels’ wagons had to be taken apart and ferried across in canoes. On June 30, Morgan and his riders reached the Kentucky border south of Burkesville, a town on the Cumberland River. Duke described the Cumberland as “out of its banks, and running like a mill-race.” His brigade had only “two crazy little flats that seemed to be ready to sink under the weight of a single man, and two or three canoes,” according to Duke. On the other hand, because the river was at flood stage, Union commanders thought it unnecessary to pay much attention to the Cumberland River, and Morgan’s men were all on the north bank on July 2. Many accounts reckon that day as the beginning of what became known as Morgan’s Ohio Raid.

News of Morgan’s moves changed Burnside’s plans regarding Buckner. Burnside, whose department included most of Kentucky, sent the XXIII Corps divisions of Brig. Gens. Henry Judah and Jeremiah Boyle toward Louisville. Burnside reshuffled some of the mounted units into a provisional division under Brig. Gen. Edward H. Hobson, his senior brigadier. Judah gave Hobson permission to move as he saw fit in regard to the unfolding situation.

One day later, the raiders approached Tebbs Bend in Taylor County, a likely spot to cross the Green River. Morgan had already been to that location. During his “Christmas Raid” of December 1862, Morgan’s men had burned the old bridge and a small stockade. Union forces replaced the stockade, but rising waters swept away the new temporary bridge on June 28. Captain Thomas Franks of the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry, sent ahead to Tebbs Bend, reported that “during the entire night, he heard the ringing of axes and the crash of falling timber.”

For about two weeks Colonel Orlando Hurley Moore and 250 men of his 25th Michigan Infantry had been stationed at Tebbs Bend. By June 27, it was clear that Morgan was moving north into Kentucky and would likely confront Moore soon. Moore abandoned the old stockade, which could not hold out against a major attack.

Heavily outnumbered, and with no artillery, Moore chose a spot admirably suited for defense. He occupied the open end of the loop in the Green River. Protected on his flanks by the river, he had only to protect a narrow front. He set his men to work on new breastworks to block the road, as well as abatis and a large rifle pit in front. Woods and ravines partially shielded his front and right. This defensive position not only would funnel the Confederate attack into a narrow front, but also give Moore’s men an unobstructed field of fire.

Under a flag of truce, Morgan demanded Moore’s surrender. Moore replied that “if it was another day he might consider the demand, but the Fourth of July was a bad day to talk about surrender, and he must therefore decline,” recalled Lt. Col. Robert Alston, Moore’s chief of staff.

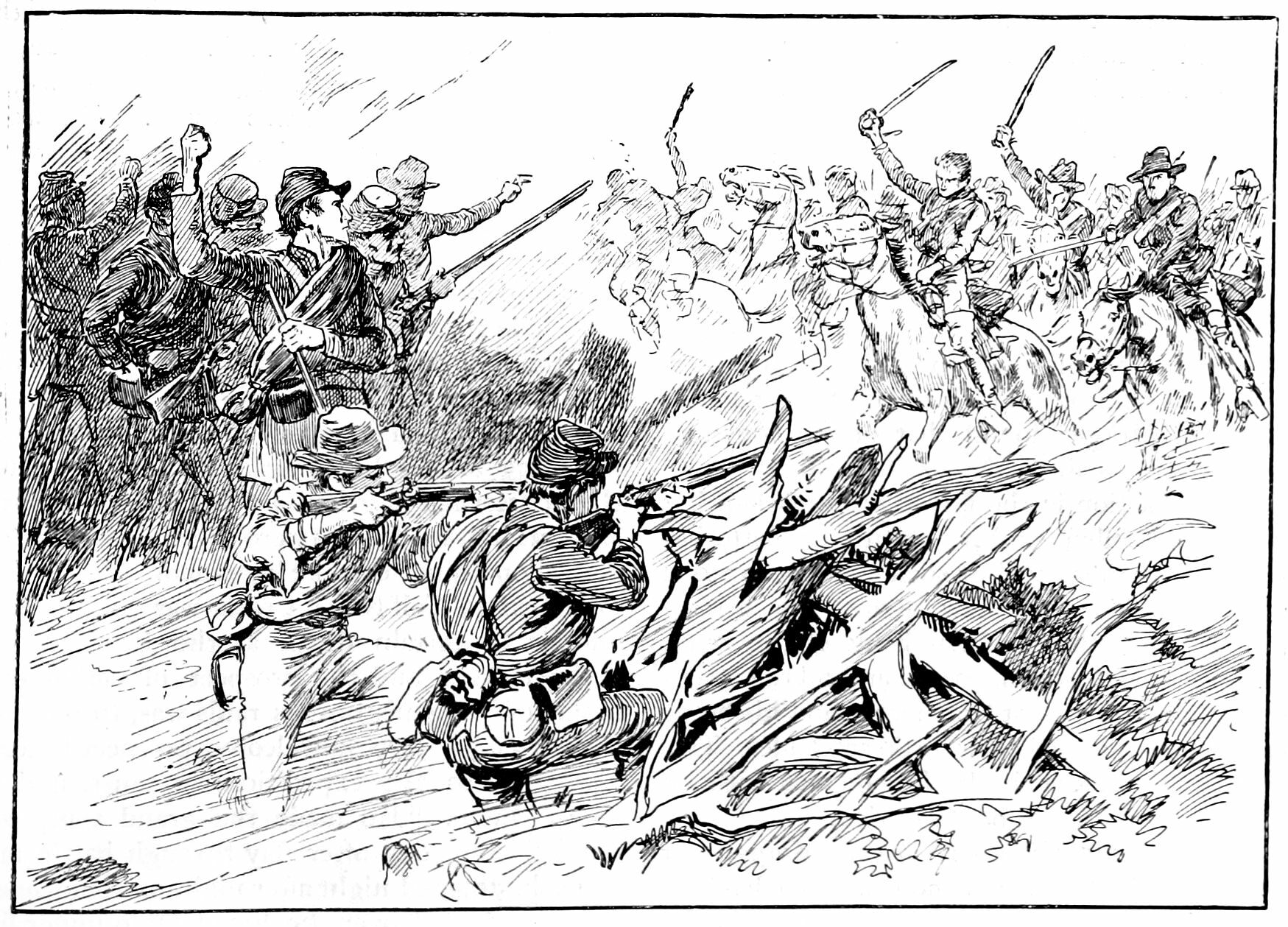

Morgan could have bypassed the stubborn Michigan troops, but he was determined to carry their position. Moore’s well-hidden sharpshooters decimated the Confederate gunners until the general ordered the artillery pulled back. Against the advice of his officers, Morgan ordered a frontal attack on foot. Three times the Confederates charged, but the sturdy Union defenses protected the defenders. Moore’s men poured a deadly fire into the attackers.

It was clear that overrunning Moore’s post would cost too much time and blood. Morgan called off the attacks late in the morning and moved to a less defended crossing. He had lost six officers and 29 men dead, including Colonel David W. Chenault of the 11th Kentucky Cavalry. Chenault had been shot while leading the first charge dismounted. He was in the process of scaling the barricade when he was slain. Another 45 men were wounded. That night Morgan lost another valuable officer. Captain William M. Magennes, Morgan’s adjutant general, was shot to death by a soldier under arrest for stealing a watch from a prisoner.

Crossing into Kentucky was a homecoming for most of Morgan’s men, who were natives of that divided state. But this also meant that they would confront some of the fellow Kentuckians who defended their state for the Union. This very situation occurred on July 5 when Morgan faced another stubborn Union garrison at Lebanon, Kentucky. Lt. Col. Charles S. Hanson commanded about 400 men, mainly from his regiment, the 20th Kentucky Infantry (Union). Hanson and his family were acquaintances of the Morgans, as both families had lived in Lexington. Roger Hanson, Charles Hanson’s brother, was a Confederate brigadier general who died on January 4, 1863, of wounds suffered at the Battle of Murfreesboro.

Like Moore, Hanson put up sharp resistance. Pushed back into the town, the pro-Union Kentuckians held on to each house as best they could. Eventually they concentrated in Lebanon’s sturdy brick railroad depot. The Rebel artillery was ineffective. Three guns were posted on higher ground, but the gunners could depress the muzzles only enough to hit the roof of the building. The defenders swept the fourth gun’s crew with their musket fire. A last-ditch dismounted charge overran the depot. In the final minutes of the battle, the Confederate commander’s younger brother, 19-year-old Lieutenant Thomas Morgan, was shot dead.

Hanson surrendered the garrison. Duke remembered their losses as “about eight or nine killed and 25 or 30 wounded.” The raiders left Lebanon immediately, herding their prisoners at the double-quick. Scarcely one hour after Hanson surrendered, a battery and two regiments of Michigan cavalry under Colonel James I. David neared the town. David did not press after Morgan, and the Rebels rode toward Louisville after paroling their prisoners at the town of Springfield.

Morgan detached two companies under Captain William J. Davis with orders to ride east of Louisville. They were to create as much commotion as possible, confuse the Union Army as to Morgan’s intentions, and then rejoin the main force in Indiana.

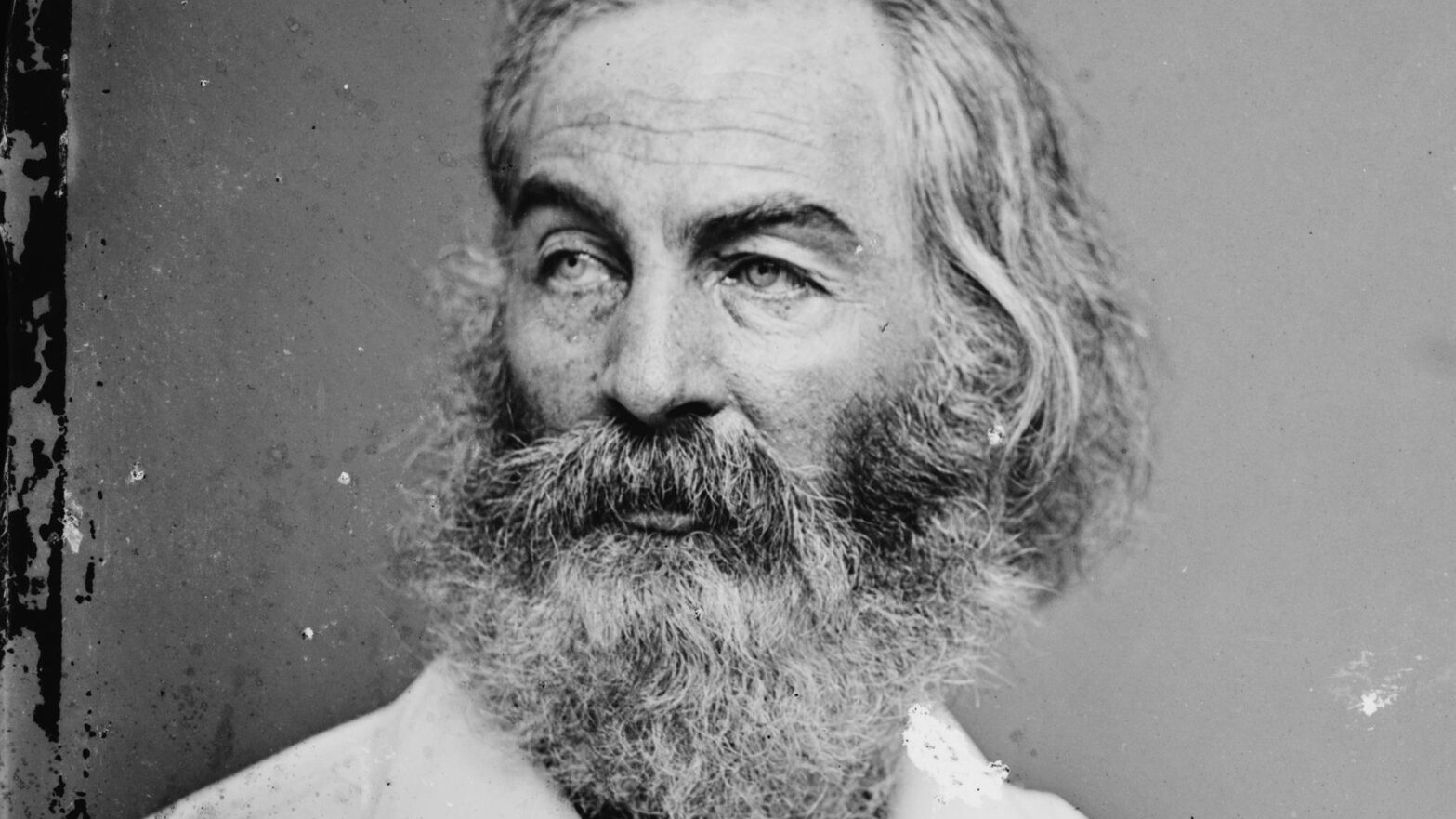

Besides sending out small detachments to move in different directions and sow confusion, Morgan also took advantage of the enemy’s telegraph system. Before the war, Morgan met a Canadian-born telegrapher named George Ellsworth in Lexington. Remembering how impressed he was with Ellsworth’s intelligence and skill, after the war began Morgan had him transferred to Duke’s 2nd Kentucky Cavalry. With a portable telegraph unit, Ellsworth could tap into the enemy wires. He could listen to messages and send new ones. His comrades had called him “Lightning Ellsworth” because during an 1862 raid, the young operator sat on horseback in a flooded creek and tapped out a message during a thunderstorm.

Each telegrapher had a distinct style that an expert could identify nearly as well as a voice. Ellsworth had a remarkable ability to imitate particular Yankee telegraph operators, giving a veneer of authenticity to the false messages dictated to him by Morgan.

While Davis headed around Louisville, the rest of the Rebels turned to the northwest, away from the big city. As they neared the Ohio River port of Brandenburg, Kentucky, on July 7, Morgan sent two officers ahead to secure boats for crossing the river.

For three weeks, Hines had been trying to find Morgan. On June 19 Hines’s men came under fire as they tried to cross the Ohio near Leavenworth, Indiana. They scattered and Hines was separated from his troops. When Duke reached Brandenburg, he found Captain Hines “leaning against the side of the wharf-boat, with a sleepy, melancholy look—apparently the most listless, inoffensive youth that was ever imposed upon,” recalled Duke.

At Brandenburg, the civilian steamer John B. McCombs pulled up to the wharf boat about 2 PM on July 7. Wharf boats were common along the Ohio, because the fluctuating water levels of the river made traditional wharfs impractical for many towns. Once the steamboat was tied up, a party of Confederate soldiers took possession of it. Another steamboat, the Alice Dean,came into sight downstream from the town. It seemed like a double stroke of luck until the course of the approaching steamer showed she did not intend to land. At that point, the Confederates steered the John B. McCombsinto the channel. They hailed the Alice Dean,and her unsuspecting captain halted. In moments, the raiders swarmed on board the second steamer. With two boats available as ferries, Morgan’s men seemed to be ready for a quick crossing of the Ohio.

Morgan’s division rode into Brandenburg, Kentucky, around 9 AM on July 8. Fog cloaked the river, so no one knew that some Union home guardsmen waited on the opposite bank. Arrayed in buildings and boats, and sheltered behind haystacks on the Indiana shore, the enemy opened fire. Rifled-muskets had no effect across a half mile or more of river, but shots from a Yankee 6-pounder dropped among the Rebels and scattered them. When the mist thinned out, Duke could see the enemy across the river. Some wore uniforms and others wore civilian clothes. Their attire indicated that they were a scratch force of the enemy.

Duke began to worry about, in his words, “how large a swarm Hines had stirred up in the hornet’s nest.” Two Confederate regiments landed across the river before the firing began and for the time being were left stranded without their horses. A pair of Parrott rifles was brought forward and drove away the gunners from the Union cannon, allowing the Confederates to resume transferring their men across the river.

Half a dozen tinclad gunboats of the Mississippi Squadron’s Ohio River Division, under the command of Lt. Cmdr. Le Roy Fitch, were available to watch for the Rebel cavalry. But Fitch had 100 miles of river to patrol with only six vessels. In places, some of the gunboats were barely able to make headway upstream against the strong currents, and enemy cavalry could take short cuts across land while the steamers chugged around great bends in the river.

One of Fitch’s boats, the Springfield under Acting Master Joseph Watson, was just northwest of Louisville at Portland, Kentucky. Watson learned Morgan’s men were trying to cross the river and headed down the Ohio after them. Aboard the Springfield were six 24-pounder howitzers. When the Springfield nosed around the bend east of Brandenburg, “A bluish-white funnel-shaped cloud spouted from her left-hand bow, and a shot flew at the town,” wrote Duke.

Watson’s guns fired at the Confederates on both sides of the river for 11/2hours. Morgan’s two Parrott rifles returned fire from “a high hill near the courthouse.” Down the slope from the Parrotts the Rebel howitzers also bombarded the Springfield. Outgunned by the enemy rifles’ range and superior elevation, the Springfield fired with little effect. At last the tinclad temporarily drew upriver out of range. Two steam transports with 500 troops arrived from Louisville, and Watson again unsuccessfully engaged the Rebel artillery.

Morgan ordered the Alice Dean set afire; however, the John B. McCombs was commanded by a friend of Duke, so the Confederates spared that steamer. Soon the entire Confederate force was in Indiana, riding north on a course that threatened the state capital, Indianapolis.

Alerted to the invasion, Indiana’s Governor Oliver P. Morton called up emergency troops. On July 9 he summoned to arms every able-bodied male citizen who lived south of the National Road in the southern half of the state. As the Rebels eluded pursuit, Morton called up the men of the northern portion of the state as well. Eventually as many as 65,000 men from Indiana reported for temporary military duty during the raid.

On July 9 near Corydon, Indiana, Colonel Lewis Jordan waited in Morgan’s path with about 450 men of the 6th Regiment, Indiana Legion, which was the state’s militia force. Jordan’s men had little or no training and were armed with a grab bag of weapons. They built a log barricade to block the road to Corydon. There was little hope of repelling the much larger invading force, but Jordan hoped to delay Morgan until more Union troops could arrive.

Another of Morgan’s brothers, Colonel Richard Morgan, led the Rebel attack. The raiders soon outflanked the Indiana militia on both sides, killing or wounding several men and capturing practically the entire force. Eleven Confederates were killed and about 40 were wounded. By this time, the Rebel force numbered fewer than 1,800.

On the same day as Corydon, Hobson’s tired cavalrymen reached Brandenburg. The Alice Dean was still burning, but because the Rebels spared the John T. McCombs, he sent that steamboat to Louisville to order transportation for his brigade. By 2 the following morning, the boats from Louisville had landed Hobson in Indiana. At daybreak he followed Morgan’s trail, passing by a burned farmhouse and a smoldering flour mill.

After Corydon, Morgan sent detachments out in different directions to screen his movements and round up fresh horses. They reassembled on July 10 at Salem, Indiana, after sweeping aside the militia and armed citizens who waited for them. Duke’s old 2nd Kentucky Cavalry captured a small swivel gun. Once used for town celebrations, the old piece was “loaded to the muzzle,” wrote Duke. Luckily for the Rebels, the militiaman in charge of the cannon fled before touching off the gun.

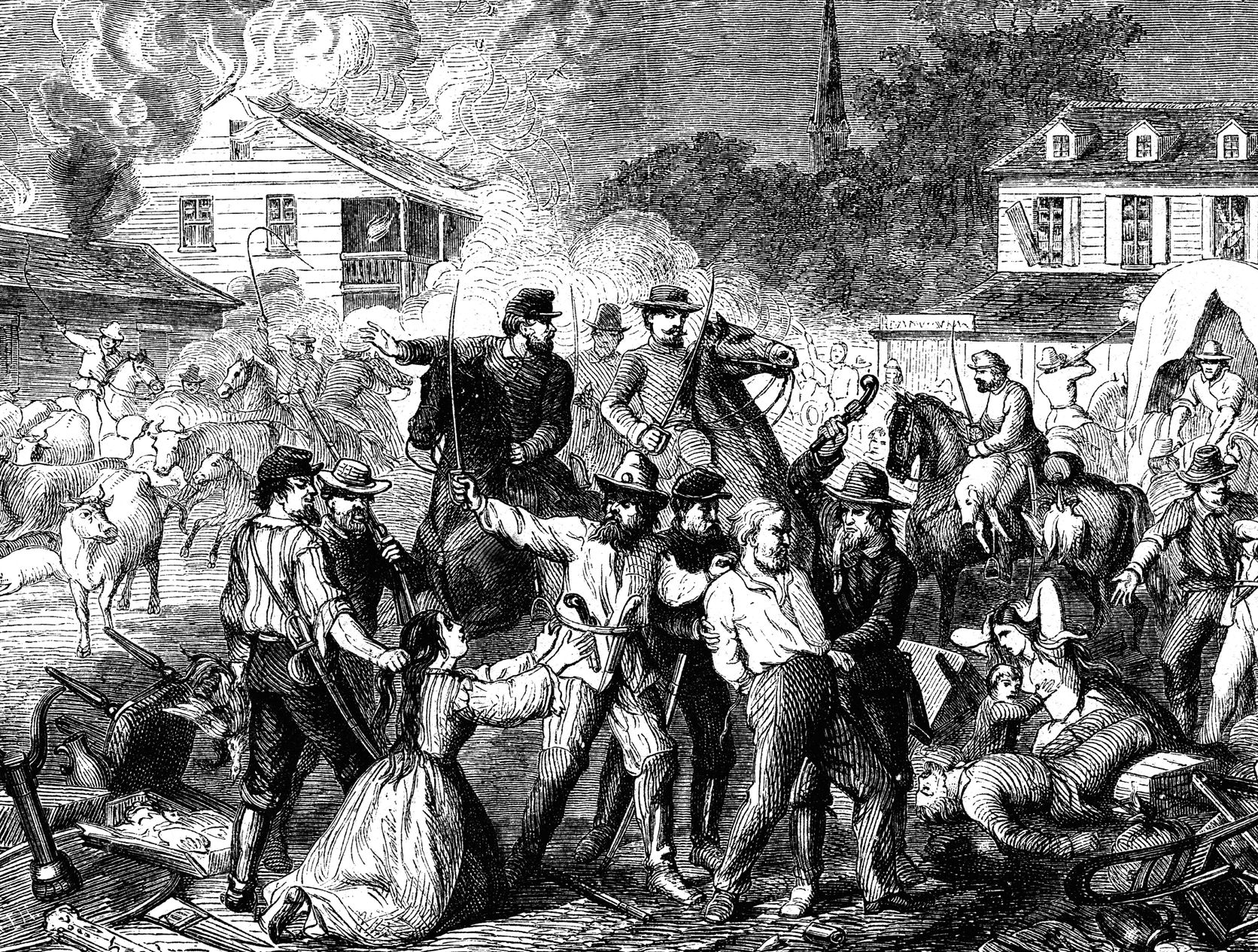

At Salem, Morgan’s provost guards were hard-pressed to prevent looting. Duke thought the plundering “seemed to be a mania—senseless and purposeless.” He saw troopers grab absurdly useless items; one took a chafing dish, and another took a birdcage with three canaries. One rider stole seven pairs of ice skates and draped them over his neck in the sweltering summer heat. “They would [with a few exceptions] … throw away their plunder after a while, like children tired of their toys,” wrote Duke.

Discipline was restored when the Confederates learned that Hobson’s cavalry had crossed the river and was only 25 miles behind them. Leaving Salem, Morgan quickly went through several towns. The raiders burned a depot and railroad bridge at Vienna. They camped that night at Lexington, about 40 miles from Corydon.

Most of the troops in Morgan’s path were untrained volunteers or militia, and nearly all of them were foot soldiers. With the raiders moving in an unpredictable path, and cutting railroads and telegraph lines, militia in any one place often had little time to assemble a credible defense. Yet even brief and futile actions served the purpose of delaying Morgan until regular cavalry could arrive.

The troopers and horses of Generals Judah and Hobson were as tired as those of Morgan. Although the citizens of Indiana and Ohio provided all the help they could to the Federal troops, there was one gift they could not give: fresh horses. All along their route, the Confederates sent out small parties that fanned out to seize all available horses for several miles beside and ahead of the main column. For remounts in the countryside the bluecoat horsemen found only exhausted horses worn down and abandoned by the fast-moving Rebels.

On July 11, Captain Davis’s detachment hoped to rejoin Morgan in Indiana. Davis started crossing the Ohio at Twelve Mile Island, 12 miles above Louisville. They used two small boats as ferries until two Union gunboats, the Springfieldand the Victory,opened fire on them. A few of the Rebels and their captain reached the northern bank of the river, but they were intercepted and captured later that day at New Pekin, Indiana.

The rest of Davis’s force was left stranded. Lieutenant Joseph B. Gathright eventually assembled 44 men; however, all but eight had to abandon their horses and arms on Twelve Mile Island. During a series of stealthy night marches, they captured enough horses to mount all the men and eventually returned to the Confederate lines near Knoxville.

Morgan approached the railroad hub of Vernon on July 11. About 1,000 men of the Indiana Legion under Brig. Gen. John Love waited outside town. Morgan sent a demand for surrender, but Love refused. Rather than lose any more time with Hobson growing nearer, Morgan slipped southeast toward Dupont and halted for the night. Hobson by this time was 17 miles away at Lexington.

Another hard day of riding brought the Rebels to Ferris’s Schoolhouse, two miles south of Sunman, on July 12. Hobson was less than 20 miles away, at Versailles. Near Sunman was another force of 2,500 cavalry under Brig. Gen. Lew Wallace. Not realizing the enemy was so near, the Union cavalry troopers did not interfere with the raid.

In answer to Governor Morton’s call, Indianapolis was filling up with soldiers. Five regiments camped on the grounds of the state capitol. Saloons were ordered closed and most regular business came to a standstill. On July 13 the 12th Michigan Battery passed through the streets.

After breaking camp on July 13, Morgan’s advance crossed the border into Ohio near Harrison, about 20 miles from Cincinnati. With a population of 160,000, according to the 1860 Census, Cincinnati was the seventh largest city in the country. Morgan had no realistic chance of attacking such a well-defended metropolis with fewer than 2,000 exhausted cavalrymen. Yet he also rejected the idea of crossing the Ohio River and heading back to the Confederate lines; instead, he was determined to ride across the state of Ohio to make his raid even more destructive and disruptive to the Union.

Riding all night on July 13-14, the Confederate raiders passed within a half dozen miles of the northern outskirts of Cincinnati. Finding the right roads in the pitch-dark night was challenging. The Rebels were “compelled to set on fire large bundles of paper, or splinters of wood to afford a light,” wrote Duke. On heavily traveled roads, it was impossible to tell which horse tracks belonged to Morgan’s leading regiments, but Duke found that “the dust kicked up by the passage of a large number of horses will remain suspended in the air … and it will also move slowly in the same direction that the horses which have disturbed it have traveled.” Duke added, “We could also trace the column by the slaver dropped from the horses’ mouths.”

Long days of incessant riding and skirmishing pressed upon the cavalry. “At every halt officers were compelled to … pull and haul the men who would drop asleep in the road,” wrote Duke. “Quite a number crept off into the fields and slept until they were awakened by the enemy.”

At Williamsburg, 28 miles from Cincinnati, Morgan allowed the men to halt in the late afternoon and rest all night on July 14-15. The column had ridden 90 miles in the previous 35 hours, according to Duke.

In pursuit of Morgan, Union cavalry units straggled into Cincinnati with worn-out horses. Burnside assembled a new force, under Majors W.B. Way and George W. Rue, and provided them with fresh mounts. Burnside rushed them east by rail, hoping to get them ahead of the raiders while sparing the horses.

Morgan pushed east through Ohio for four more days. Although they outran the regular cavalry, the Confederates confronted militiamen and armed locals everywhere they went. The toll of countless skirmishes, ambushes, and sniping whittled away at Morgan’s ranks and delayed their progress. Besides picking off Rebel horsemen, the militia also busied themselves chopping down trees to block the roads, further slowing Morgan down.

Roughly 150 miles east of Cincinnati, the Rebel horsemen reached Chester at 1 PM on July 18. They were only about 10 miles from the Ohio River and a crossing that offered escape into West Virginia. For some hours, the Rebels lingered at Chester to allow their scattered and stretched column to unite. They also searched in vain for guides who were familiar with the fords along the river.

Morgan planned to cross the Ohio just above Buffington Island. Roughly one mile in length and a quarter of a mile across, the island spilt the river into two channels. The western channel, known as Buffington Chute, was a narrow passage between the island and the Ohio shore.

The long halt at Chester delayed their arrival at Buffington Island until dark. A regular officer, Captain D.L. Wood of the 18th U.S. Infantry, held the ford with about 200 men rounded up at Marietta. Wood’s men were one of numerous detachments scraped together to hold every possible crossing point open to Morgan. With two old guns formerly used only for firing salutes, Wood reached the ford near Buffington Island only one day before Morgan and put his men to work building some defenses.

Morgan’s advance took Wood’s detachment for a force of 300 regulars with two guns. Duke urged an immediate attack to secure the ford and cross the river as soon as possible, but Morgan pondered several reasons to avoid quick action. He knew the risks of a night attack on a fortified position and of crossing in the darkness a river swollen by heavy rains. And, Morgan’s men were down to about five cartridges each, and there were only three rounds apiece for the artillery.

When the 5th and 6th Kentucky Cavalry came to within 400 yards of the enemy works, they decided to wait for dawn before rushing the enemy entrenchments. As soon as it was light enough to press forward, they found the works had been quietly abandoned during the night. Both Union guns were rolled off the bluff into the river.

Finding the works empty, the two Kentucky regiments were sent after Woods’ retreating Union troops. Meanwhile, General Judah with his staff advanced down a road that was bordered on both sides by fences that led to the river. They were investigating disturbing reports that Wood’s men had fled. A Union gunboat had withdrawn, and Morgan was already escaping across the river.

Fog cut visibility to about 50 yards. In the mist, the general’s party stumbled into Duke’s cavalry. Duke told Judah later that “he could not have been more surprised at the presence of my force had it dropped from the clouds.” Firing broke out in an instant. Taken by surprise, Judah’s party was pushed back and scattered. Their gun was taken before it could fire a shot.

About 50 of Judah’s men were shot or captured, including some of his staff officers. Most famous among them was 65-year-old Major Daniel McCook. The major’s family was known as “the Fighting McCooks.” Nine of his sons and six nephews all served in the Union Army. Although too old for field service, McCook joined the army in 1862 and became a paymaster. He left his routine duties to volunteer as an aide for General Judah and was shot in the early minutes of the clash near Buffington Island. McCook died of his wounds two days later. He was the highest ranking Union officer killed on Ohio soil during the war.

Judah and the other survivors fell back to join the rest of their force. “Obstructing fences prevented a charge by my cavalry,” wrote Judah, but his muskets and artillery hammered the enemy troopers. Hobson’s men were not far behind those of Judah, and at 6:30 AM they attacked Morgan from the west.

The report that the gunboat on the river had withdrawn was not true. Most of Fitch’s gunboats were deployed farther downstream. The army had not conveyed much solid intelligence about Morgan to the Navy, and Fitch in part relied on newspaper reports to decide where to station his vessels, but he was on hand with his gunboat, the Moose.

Pressed by more than twice their number in cavalry, the Confederates retreated north along the riverbank. One and a half miles above Buffington Island, they tried to ford the river under cover of a Parrott rifle and a 12-pounder. Armed with four 24-pounder Dahlgren guns, the Moose opened fire on them from the river. After the Rebel gunners were killed or driven away by the Dahlgrens, Lt. Cmdr. Fitch sent a landing party to capture the two cannons.

Some of Morgan’s men were partway across the river when the Moose opened fire on them. Most of the men turned back to the Ohio bank. But several of Morgan’s men had been shot from theirs saddles. Some of their horses remained standing still in the water, while bodies and pieces of Confederate clothing and equipment floated downstream past the steamer.

On the shore, the Rebel riders were exposed along a narrow ledge of beach. Men scrambled up ravines and disappeared into the woods. Captured wagons and carriages were abandoned by the edge of the river. “The road along the bank was literally strewed with his plunder, such as cloth, boots, shoes, small arms, and the like,” wrote Fitch.

The Battle of Buffington Island all but ended Morgan’s raid. Of the force involved, 750 men, including Colonels Duke and William Morgan, were captured. The remnants of the expedition rode northwest back into Ohio as far as Nelsonville, then turned northeast on a course converging with the Ohio River.

Twenty miles upriver, Morgan tried to cross the river and reach Belleville, West Virginia. The Mooseagain opened fire on the soldiers fording the river, this time cutting the Confederate force in two. Several men were killed in the water. Stovepipe Johnson made it to West Virginia with 300 men, but the rest of the force followed Morgan to make another try at getting home.

Fighting their way northward and eastward for another week, the dwindling force of raiders tried to maneuver around Union troops and find their way across the Ohio. Brig. Gen. James M. Shackelford, leading 2,600 Union horsemen, caught up with Morgan at Salineville on July 26. Shackelford’s force killed 23 Confederates and captured nearly 300 men. Salineville would be the northernmost battle of the Civil War.

Morgan escaped from Salineville with only a handful of men. A few hours after the clash with Shackelford, the remaining raiders reached West Point in Columbiana County, Ohio. They were just past the northern tip of West Virginia and about 10 miles from the Pennsylvania border. But the appearance of more Union cavalry dashed any hope of getting out of Ohio. Burnside’s use of the railroads had enabled Major Rue and elements of the 9th Kentucky Cavalry to catch up with Morgan. Before Rue could close in, Morgan surrendered to one of his prisoners, a militia captain named James Burbick. The captain agreed to parole Morgan and his remaining men.

Sparing a notorious raider such as Morgan from prison was unacceptable to Rue and his superiors. Burbick’s decision was overruled on the spot; an official inquiry later found that because he was not a regular officer, he had no authority to grant paroles. Rather than being treated as prisoners of war, Morgan and several of his officers were jailed in the Ohio State Penitentiary as common criminals.

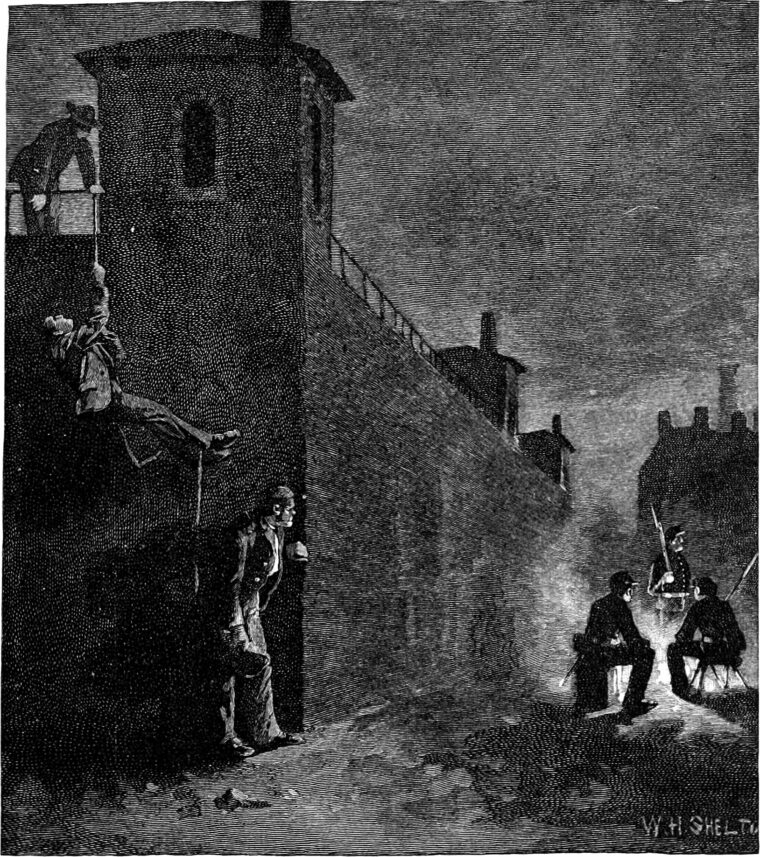

On November 27, 1863, Morgan and six of his companions broke into a ventilation shaft that ran under their cells. Soon they were outside the prison and scattered into the rainy night.

Hines and Morgan had some money they had kept hidden from the guards. The pair bought tickets to Cincinnati aboard a train leaving early on the morning of November 28. Morgan struck up a conversation with a Union officer in a passenger car and shared a flask of brandy with him.

At daybreak, when their train reached the edges of Cincinnati, Morgan and Hines moved to the platforms at either end of their car. Both men yanked on the bell ropes to activate the emergency brakes. When the train slowed down, they jumped off. Eluding arrest, they paid the owner of a skiff two dollars to row them across the Ohio. Once in Kentucky, they found Confederate sympathizers to help them reach the Confederate lines.

Again, Morgan went back into the field as a cavalry raider. He met General Hobson once more when he captured the Union officer during an attack on Cynthiana, Kentucky, on July 11, 1864. Less than two months later, Morgan’s career ended when he was shot dead during an attack at Greenville, Tennessee, on September 4.

Although a spectacular achievement in so far as traversing two Union states, Morgan’s Raid accomplished little of strategic value. The cavalry force slashing across the Ohio Valley was too small to accomplish any permanent objectives, and it could ill afford the losses incurred in sharp clashes such as those at Tebbs Bend and Lebanon. The raid deprived Bragg of many of his most effective cavalry officers and men. Tying up more than 100,000 enemy troops meant little when the massive Union Army could easily spare them for a few weeks.

More important than any tangible results, though, Morgan’s Raid at least for a short time provided hope for a Confederacy reeling from the twin disasters of Vicksburg and Gettysburg. Morgan’s men could point to an impressive toll of damages. They took and paroled 6,000 soldiers, which was almost three times their own number. During the raid, they burned 34 bridges and cut railroads in more than 60 places. In Ohio alone, the raiders captured about 2,500 horses. As many as 4,375 people across 29 Ohio counties filed damage claims. The state government mobilized approximately 50,000 militia to deal with the Rebel foray. After the war, the expedition remained a proud achievement to the ex-Confederates of the trans-Appalachian theater of the war, and a vivid memory to the inhabitants of a broad and otherwise peaceful swath of Indiana and Ohio.

Morgan’s actions, however glamorous, served to illustrate that it is the infantry that holds the ground that is taken. Even Sherman with all his success in the Southeastern campaign, did not propose to hold all the area he passed through. The morale boost to the Confederacy was certainly welcome but in the end did not alter the course of the war.