By Peter Suciu

Many famous photos of military uniforms and personalities are actually taken from vintage postcards. And while today many vintage baseball or football cards can fetch thousands of dollars, military postcards essentially have been forgotten. Even at military shows, they tend to be buried in obscure piles. Yet military postcards can still serve as a window to the past—both the individual participants and the nations they served.

Postcard collecting today is very much a niche hobby, and the collecting of military cards is a niche within a niche, one that overlaps the greater category of collecting militaria. Postcards first became popular in the late 1860s, and saw a resurgence between the years 1894 and 1914. Cards of all sorts were popular, including those devoted to famous people, cards for holidays, advertising, and topical events. “Postcards have always been the means of communication since the late 1800s,” says Alan Gottlieb, a dealer in postcards for Oldpostcards.com. He says that, all things considered, it was a more patient time. “Today, everything is instantaneous such as emails and text messaging.”

The early age of postcards was also the age when military cards first gained popularity. The history of such cards precedes the widespread use of film cameras. “The first postcards were actually not photos, but lithographs, like the earlier trade cards,” notes Eric Larson of CardCow.com, who adds, “U.S. picture postcards became popular after they were first made available at the World Columbian Exposition in 1893.”

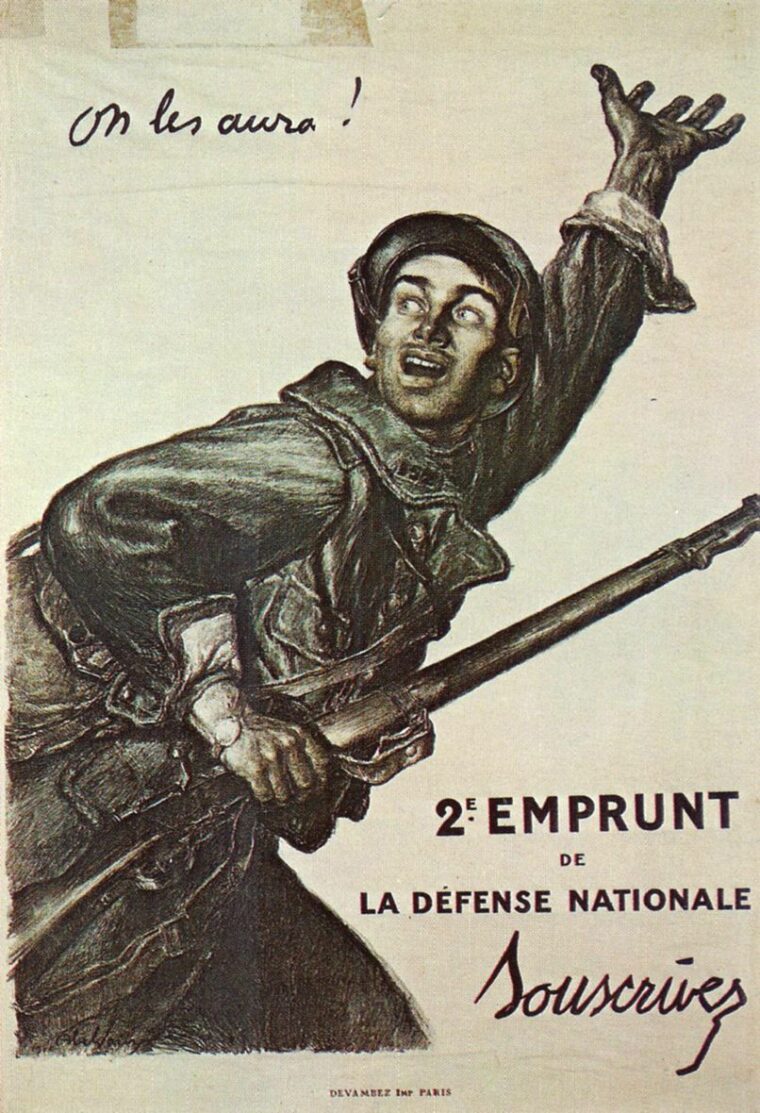

Postcards were first issued in the late 1860s, and military cards made their debut in a meta-phorical baptism of fire. Both sides during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 printed cards depicting the soldiers of the era. These early cards were used as propaganda tools, and for the first time folks back home received a visual glimpse of the war at the front. These early cards also served as a way of setting the tone of the nation. While the German cards of the post-Franco-Prussian War showed a bright future, the French cards took a more somber tone that was more in keeping with the nation’s crushing military defeat.

The first true military postcard was offered for sale on September 29, 1870, and was issued by the German Army Corps Society. It was uncolored (black and white), illustrated with the Red Cross symbol, signed by the commander of occupied France, and authorized by German occupation headquarters. The French also issued cards, part of a series of sketches drawn by Leon Besnardeau, a well-known stationer in Sille-le-Guillaume. These cards were reproduced on card stock and were used for homeward correspondence by soldiers in training.

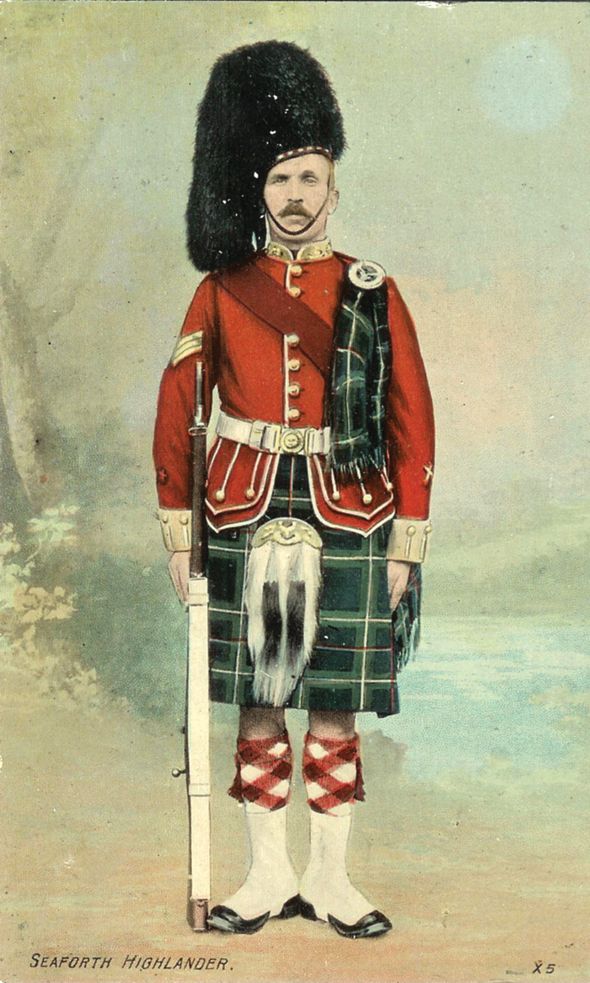

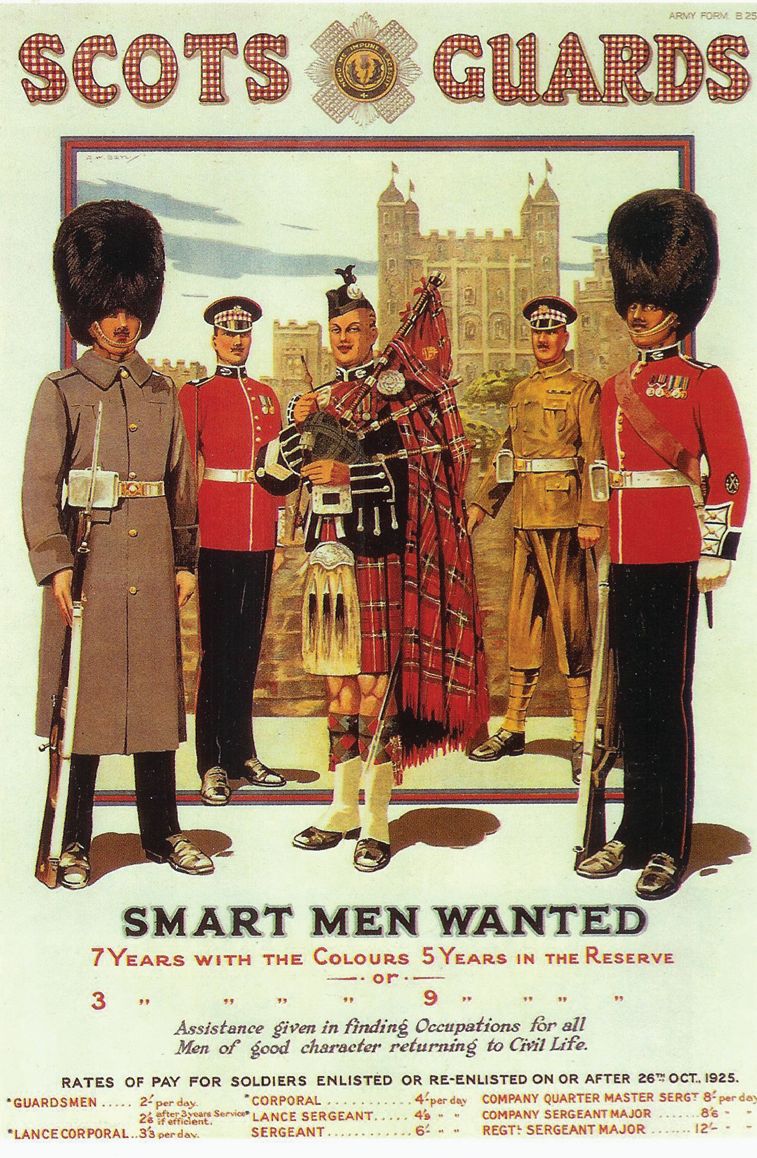

Many nations began to print military postcards and illustrations, and for a time lithographs remained far more popular than actual photographs. The British, being master propagandists as much as master politicians, were keen to highlight their various exploits, and the cards were used to offer glimpses from the empire on which the sun never set, while also being used to recruit soldiers to join the ranks of the Queen’s army. These included a variety of card sets.

Interestingly, many of Queen Victoria’s enemies did not issue postcards until the Second Anglo-Boer War, when cards depicting the Boer struggle were printed. Other cards illustrating conflicts from a Eurocentric view were printed for a variety of wars, including the Boxer Rebellion in China, the Russo-Japanese War, and the Balkan wars. None of these survive in great numbers today, in part because of the limited appeal of the conflicts to earlier collectors and in part because many of the cards contained strongly nationalistic propaganda. The latter aspect made the cards less desirable, especially to the masses who didn’t necessarily agree with the politics involved and thus likely never bothered to save the cards.

For much of the late 19th century, military postcards were primarily a European affair, one that Americans didn’t take part in until much later. “There were some foreign picture postcards before 1893 and some U.S. postal cards, but I don’t think there were many military cards until the very late 1800s,” says Larson. Even when the United States got into the act, the number of cards was somewhat limited. As a result, postcards chronicling the events of the Spanish-American War were actually far less common than one might expect, especially considering the widespread national exuberance over the war. It was far more common for American soldiers to have photographs made of themselves and mailed home. As a result, actual cards from the Spanish-American War are highly sought by collectors today. But so too are personal-photo military cards, often because these are truly one of a kind.

“Real photo military cards are typically the most desirable, since they were often made in very small numbers,” says Larson. “Printed cards may have been made by the thousands or tens of thousands. I’m not sure if I’d say there are certain countries that are more desirable than others, but cards from smaller, more obscure places and smaller conflicts are rarer than cards from Europe or the U.S.”

And while the larger conflicts may seem to be the more desirable, it is actually the lesser- known wars and sideshows that have piqued the interest of collectors. “Mexican Revolution cards with Pancho Villa are very sought after,” says Larson. “Basically, cards that cross over into multiple topics may bring the highest prices.”

It was another, greater war that marked the end of the highly detailed postcards, notes Larson. “World War I happened right after the golden age of postcards.” Ironically, while postcards as a collectible, mini artwork practically died as a result of the World War I, postcards with simple art were actually sent in record numbers during the conflict. Some of these, such as the embroidered silk cards that were made in France during the conflict, remain the most desirable of all cards among collectors today.

While World War I ended the golden age of postcards in general, it was also a boom time for military cards. This duality of events isn’t lost on modern collectors, who note that hundreds of thousands of cards may have been printed, many of which survive today. “The Germans have, for World War I, by far the most cards,” says Chris Boonzaier, a collector of paper documents and postcards. He says that this is primarily because the Germans simply printed far more cards than anyone else. “Traditionally, they have had lots of cards, but cameras were also widely spread in Germany, and as a result there are zillions and zillions of photo postcards.” Boonzaier notes that the cards were also quite well made, like most German products—military or otherwise. “As far quality and numbers, they lead the way.”

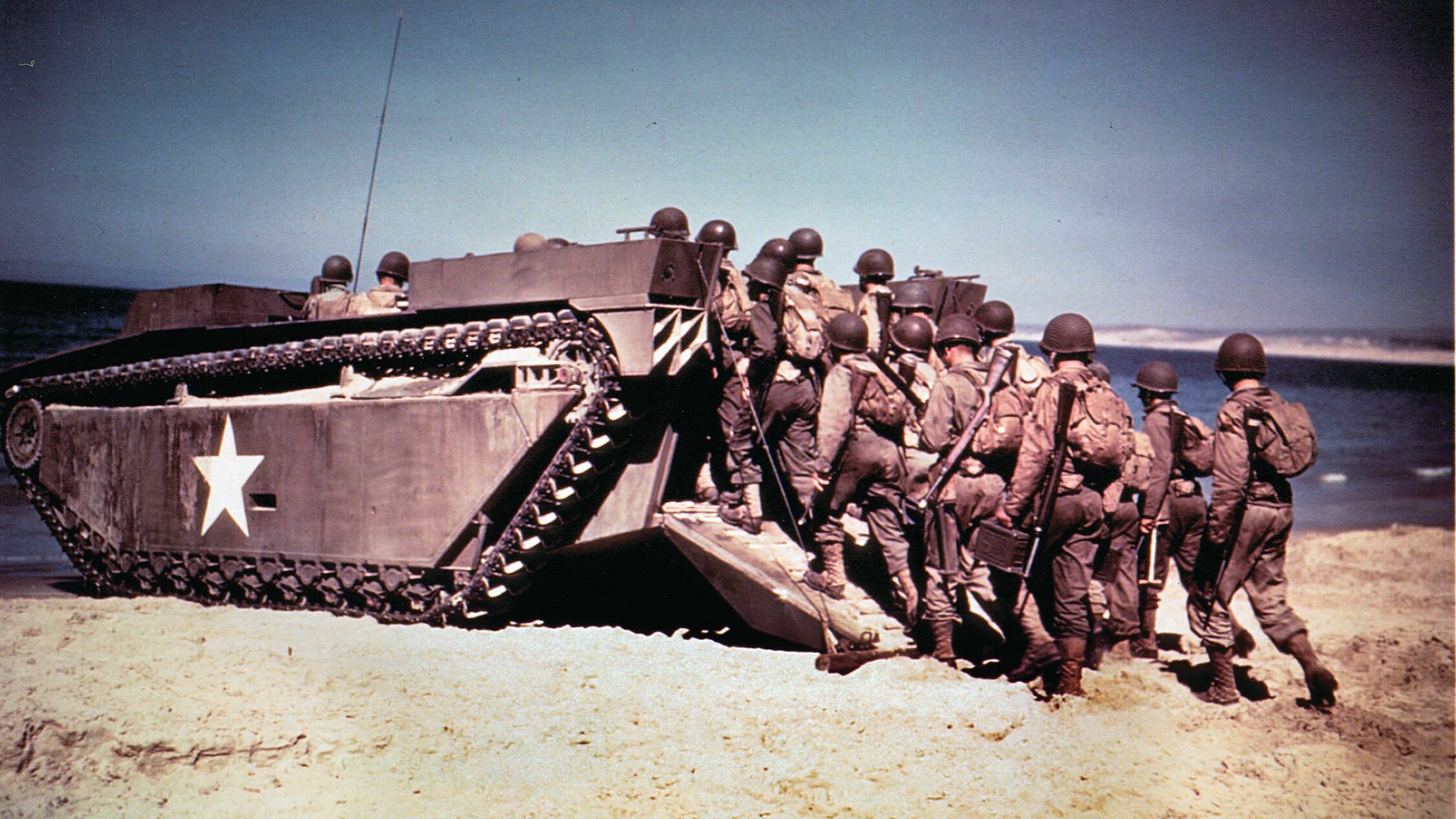

Military postcards saw a resurgence after the war, but never to the levels of prewar cards. The closest came in Nazi Germany, as the master propagandists churned out cards in great numbers before the war and then following the Third Reich’s many early successes. As the tide turned against Hitler and his minions, the cards dwindled in numbers until practically no new cards were being printed. Thus, original World War I cards remain far more numerous than World War II cards. Boonzaier adds that this relative plethora has been good for collectors. “With German World War I cards,” he says, “you can choose one of hundreds of different themes to concentrate on. For collectors this is fantastic.”

Boonzaier further notes that French postcards from the World War I era come in a distant second, and that, whereas the British had been early adopters of cards during the zenith of their empire, by World War I such postcards weren’t nearly as popular in Great Britain. “The British seem to have favored letters,” he says.

For this reason, those fewer British cards have become the ones most sought after by collectors. Among the holy grail of such postcards is one of Canadian Hospital No. 2 in Le Treport, France, showing an operation on a soldier about to begin. This card reportedly sold for nearly $1,000 on eBay a few years ago, but Larson says that most postcards sell for under $20, and many common cards retail for about a dollar. This makes it an easy hobby to get into and. except in the rarest occasions, one with relatively few fakes.

Nor is finding vintage military postcards all that difficult. While dealers such as Larson and Gottlieb have sites devoted to sales, many dealers have moved to online auction sites. “EBay all the way,” says Boonzaier. “Most of the major postcard dealers are online and on eBay.”

Where new sellers need to be concerned is not so much with outright fakes, but rather with the millions of reprints of original cards. Museums around the world, notably those in Europe such as the Imperial War Museum in London, sell such reprints, and they should not be confused with the originals. However, it is worth noting that many of the reprints themselves are now out of print, and these “vintage” cards can be considered collectibles in their own right. Collectors should be wary of whether a particular card being sold was something produced by original printers in 1915, or whether it is a 1970s or 1980s reprint. The good thing about reprints is that they tend replicate the front artwork of the cards quite well, although purists will note that the paper on which they are printed is quite different.

Collectors tend to be very specific with regard to eras, rather than collecting a wide spectrum of postcards. Unlike baseball cards, there is little in the way of pricing guides, so collectors must pay whatever they feel is appropriate for the cards. Condition of cards is a big factor in determining the price.

Card sellers say that the grading of military postcards is not entirely dissimilar to that of stamps or coins although nowhere near as advanced. “Postcards are not graded like sports cards,” says Gottlieb, noting that many factors come into in play. “The professional graders for sports cards once tried grading postcards, but there was little demand for them [grades] in the postcard market.”

More important, unlike baseball or other sports cards, military postcards come in the mailed variety, although many were never sent through the post. “Some collectors only care about the interest of the topic or postal marks, while other collectors for high-end expensive cards look for perfect corners and clean cards,” says Gottlieb. “It is not very hard to tell the faults of a postcard on your own.” And unlike sports cards, the rarity is only part of the issue, adds Gottlieb. “If I do not have a card that I collect, the grading is of little importance. In the future, I can always upgrade or I may never see that card again.”

In addition to determining a card’s rarity and condition, proper preservation is also an issue. Postcards, being paper, should be stored out of direct sunlight and under UV protection, if possible, when being displayed. Protective sleeves such as those from makers such as Ultra Pro, are also recommended. As cards can fade, the more valuable variety should be kept in albums or archive boxes whenever possible. “A good way to protect postcards is to use an acid-free protector,” says Gottlieb. “For my personal collection of cards, I use the Ultra Pro Platinum Series Protectors for a three-ring binder.”

Regardless of how military postcards are preserved, it remains a fact worth noting that the cards capture images that are often not to be found in history books and, thus, offer a unique perspective of the era. After all, it isn’t every piece of militaria that allows you to literally look back in time.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments