By John Wenner

With the bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861, the Civil War began in earnest. The first recruits, on both sides, were completely uninitiated in the ways of military life. They had to learn in camp how to be soldiers—living in the open, sharing tents, constructing fortifications, drilling, marching in step and following commands. Included in their train-ing was instruction in proper military conduct, enforced by a system of punishments for infractions that would prove as vexing to the soldiers of the Civil War as it had to every army since the time of Alexander the Great.

The Confederate provost system was one approach to maintaining proper military discipline in the southern armies. The provost system was based largely on British precedents that had existed since the Revolution and was mainly restricted to purely military police functions. Many provost duties initially were performed by civilians, although the Confederate articles of war provided for military provost marshals and military courts to try personnel charged with violating military law.

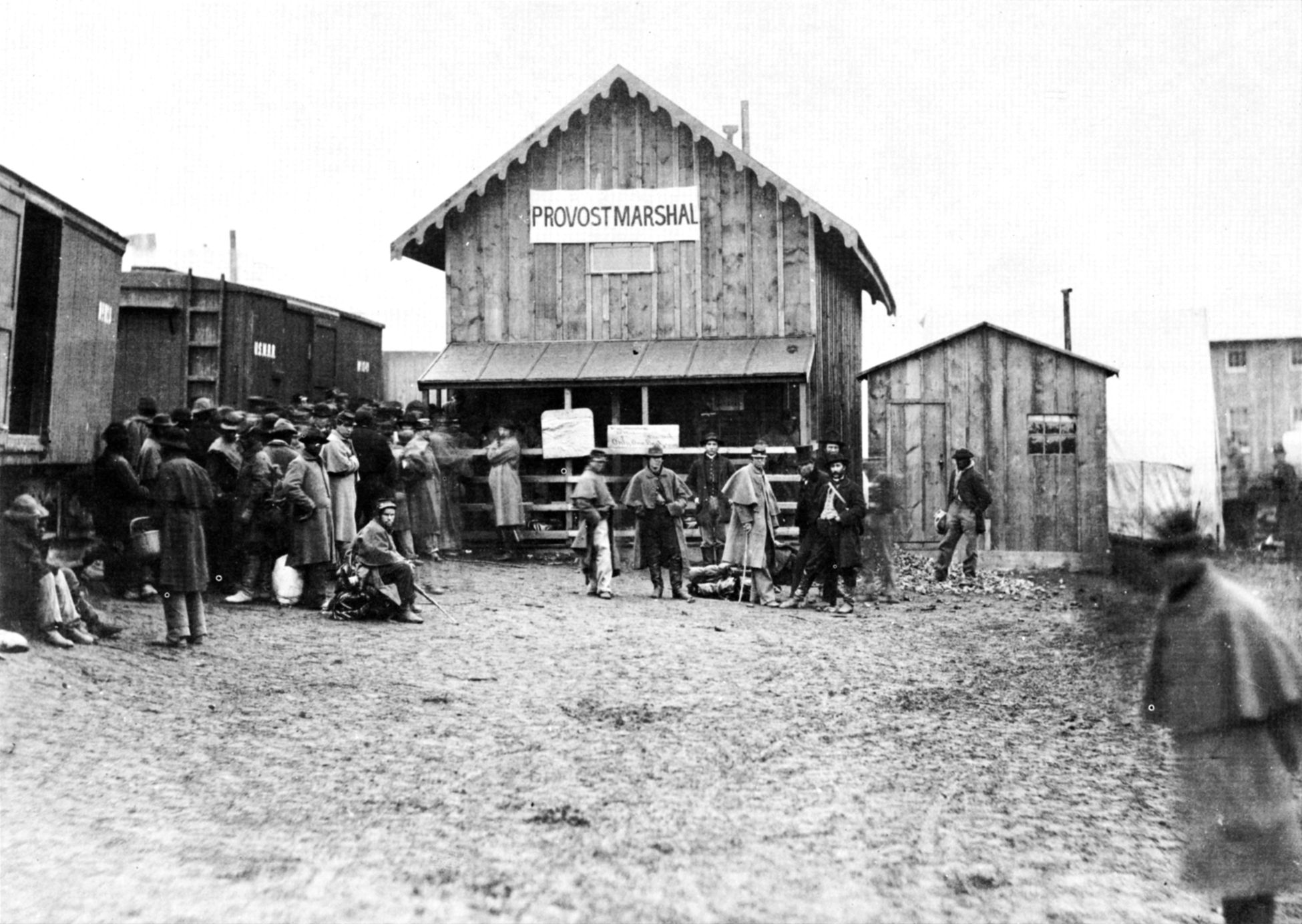

The Provost Guard Receives Its Duties

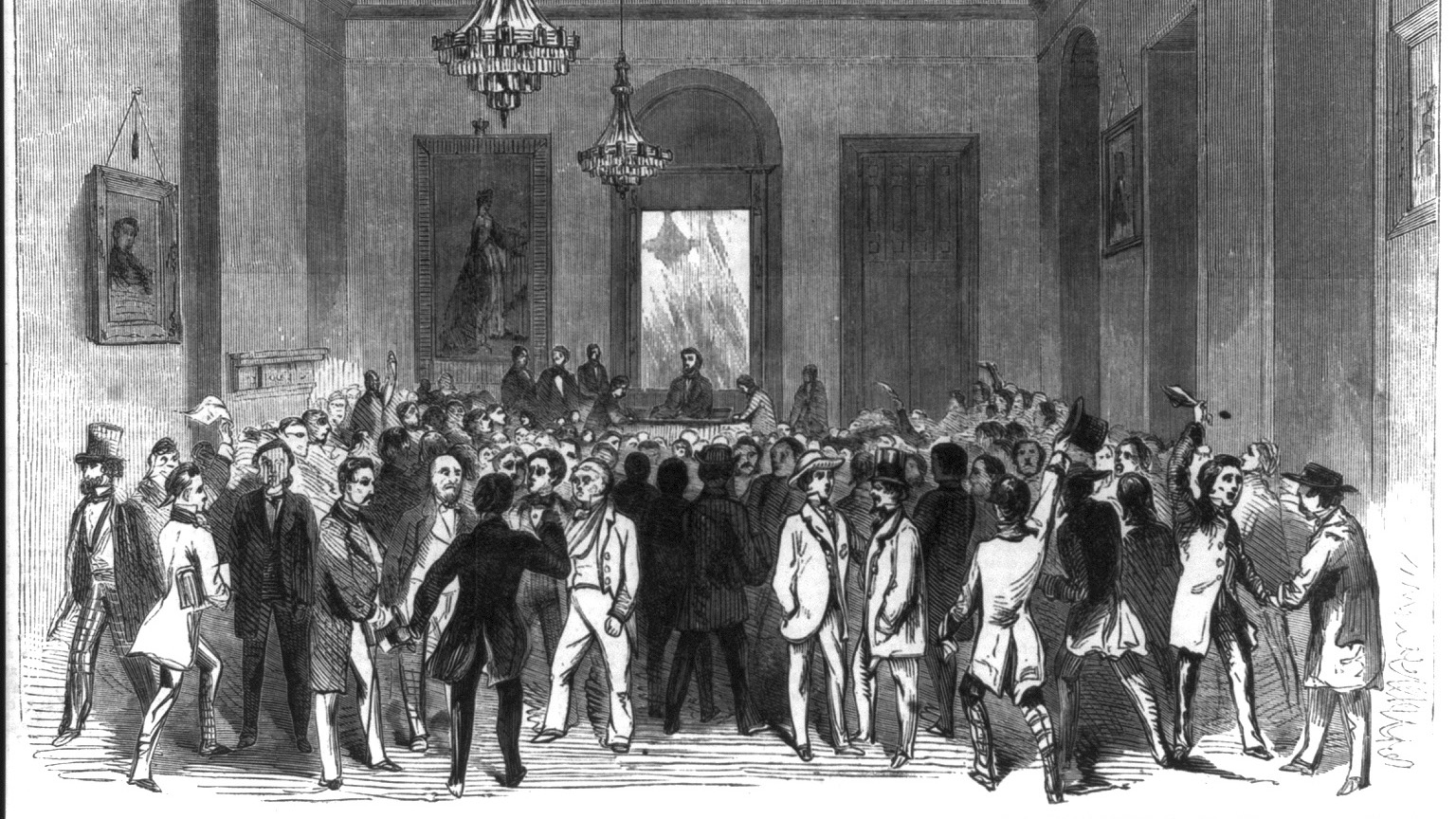

In 1862, a subsequent act of the Confederate Congress authorized a military court for each army corps and a provost marshal to execute its orders. The jurisdiction of these courts included offenses against the Articles of War and against Confederate and state laws. An 1863 report of the Army of Tennessee mandated: “A provost marshal general will be assigned to duty at army headquarters with one assistant. Corps commanders will detail a field officer, with one assistant, for duty at corps headquarters, a captain for division headquarters, and a lieutenant for brigade headquarters. These officers will report regularly to the provost marshal of the army.”

As the war dragged on, Southern governors tried and mostly failed to gain direct control over the provost guard as it increasingly affected the public. They wanted at least to rein in its authority, especially its existence outside the operational sphere of the armies, to prevent abuses against the civilian population. But legislative efforts were generally unsuccessful in limiting the authority of provost marshals over the citizenry. The governors’ fears of such an extension of power would later prove justified as the provost guard’s original purpose—to preserve order in the armies—was greatly expanded by the pressures of war.

Should Their Powers Extend Beyond the Army?

One example of the provost guard’s increased authority was the monitoring of transportation services such as trains. The intention was to decrease the growing rate of desertion within the Confederate Army and to restrict the movement of Union spies. A system of passes was devised to regulate travel, annoying citizens and soldiers alike. Vigorous debate continued among members of the Confederate Congress who believed that provost marshal powers should not extend beyond the army. But as the Confederacy’s military fortunes declined, the army often ignored relevant provisions. Military necessities had more weight than the political niceties of catering to strict constitutionalist governors and other state officials.

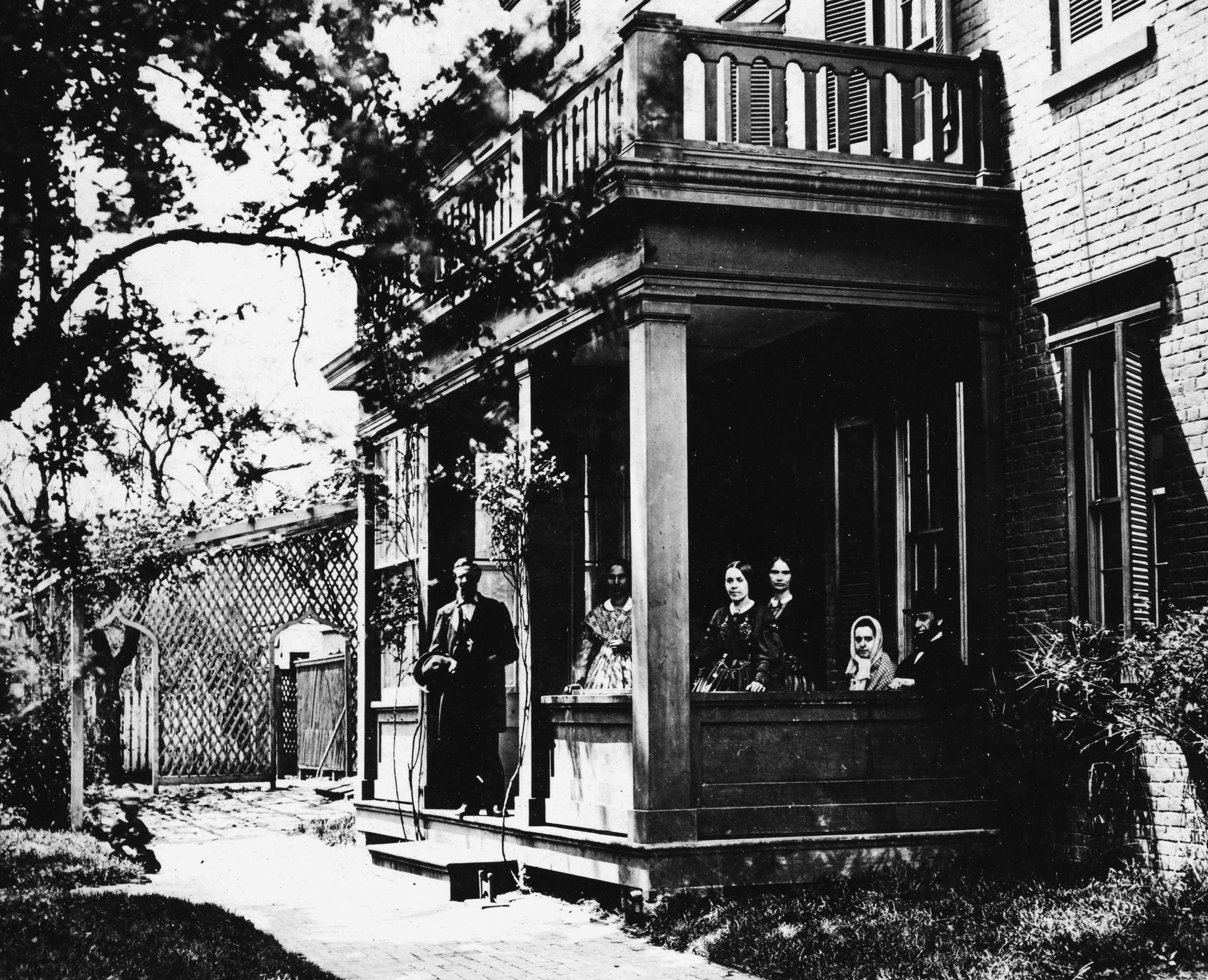

The widespread unpopularity of civilian passports grew as battlefronts expanded, and Confederate citizens increasingly were subject to the provost guard’s control of every individual’s right of movement. Even General Robert E. Lee’s wife, Mary Anne Custis, was delayed and questioned by provost guards during a trip before her identity was confirmed. Over time, oppressive measures continued to be hotly debated, and provost authority was to a degree curtailed in areas outside the actual fields of military operations. Additionally, provost marshal appointments were carefully controlled in rear areas.

Early on, Confederate commanders requested authority to raise companies of exempt men to be used by the provost marshals to enforce orders. In addition, local defense units were organized from the reserve corps and those unfit for active service. In at least one major department, a provost organization was formalized on a district and subdistrict basis, and necessary police officers were appointed, with militia being used as provost guards to keep order and guard public property, prisons, and bridges. In many regions, the absence of any other manpower made the use of the provost guards inevitable. And while there were some complaints from regular troops about their being detached for provost duty, there were also numerous instances of men using provost duty to avoid the rigors of active service, a practice that reached serious proportions in the last two years of the war.

The Provost Chain of Command

Confederate congressional representatives called for steps to prevent officers from abusing their power to grant exemptions from conscription in certain areas. It was feared that enrolling officers who stayed too long in one locality (and who themselves were frequently averse to hard, frontline service) would become overly familiar with local citizens and thus more prone to keep eligible men out of the army.

In military departments, the provost chain of command was from subdistrict to district and finally to department-level provost marshals. In the field armies, as well, a chain extended through the levels of command from brigade through division and corps. Staff responsibilities were fairly well defined, with provost guards receiving their orders either directly from formation commanders or through the appropriate staff officers. Even in the most remote commands, the provost machinery was firmly in place, and sometimes entire brigades were placed on provost duty.

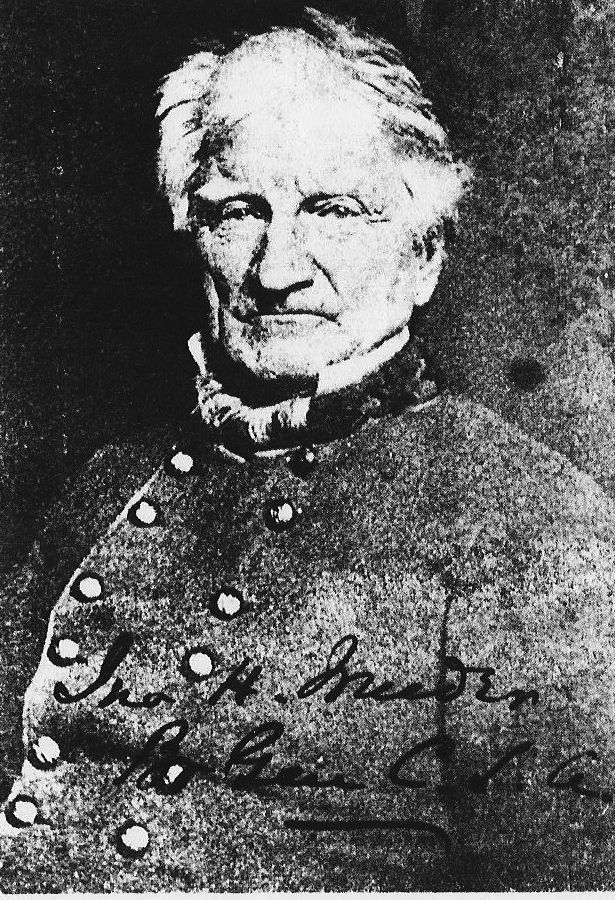

It was not until February 1865 that a bill was introduced in the Confederate Senate providing for the formal appointment of a provost marshal general. The purpose was to replace the long-serving Brig. Gen. John H. Winder, who had just died, and name Brig. Gen. Daniel Ruggles as his replacement. When Winder placed Richmond under martial law “to ferret out spies and other undesirables,” his undiplomatic methods caused further repercussions, and his battles with the city’s hospitals and board of surgeons did nothing but increase his unpopularity. Leaving in June 1864 to become the commandant of the infamous Andersonville prison in Georgia, Winder eventually would command additional southern prison camps and function as provost marshal general until his death on February 7, 1865.

A Constant Battle Against Vice

Robert E. Lee never doubted the need for strict discipline. In Lee’s opinion, too much reliance was placed on the soldier’s innate “merit” and not enough was done to instill instinctive obedience. He believed the primary duty of the Confederate provost guard was the maintenance of discipline. Beyond that, Lee looked to the provosts to perform the time-consuming responsibilities of crime prevention and investigation of crimes committed by military personnel, as well as escorting offenders, apprehending deserters, and rounding up absentees.

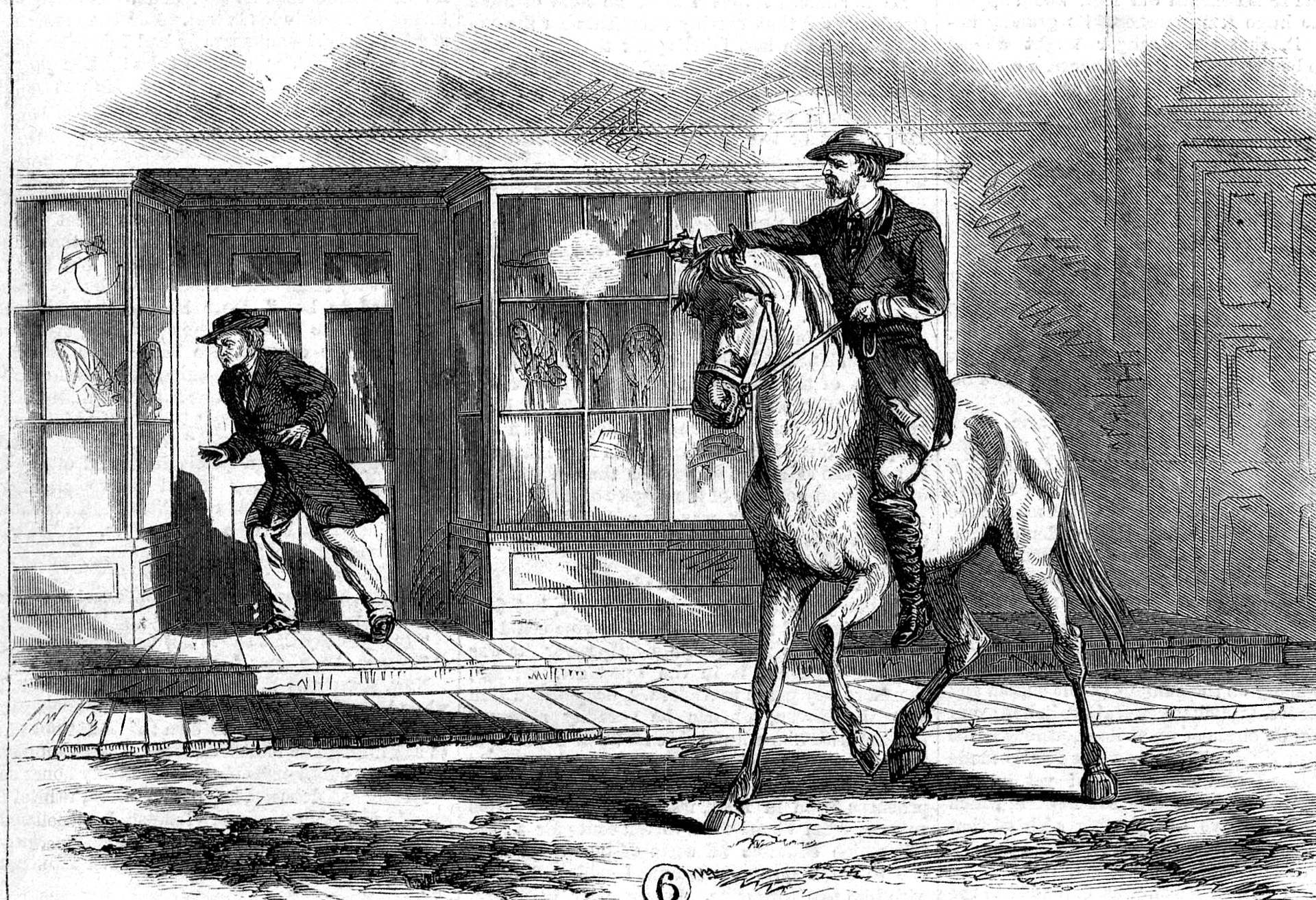

In the constant battle against vice, Confederate military policemen encountered looting, pillaging, lax military security, and the soldiers’ time-honored pastimes of gambling and prostitution, all complicated by the ever-present liquor-related offenses. In May 1862, the Confederate Congress attempted to control liquor consumption by passing legislation to punish drunkenness in the army. Such enactments, noted one historian, “had about the same deterrent effect as King Canute did in his famous encounter with the North Sea.”

A highly visible provost was essential for a measure of acceptable discipline, and provost marshals were charged with functioning as policemen, magistrates, and jailers. The Confederate Articles of War in 1861 provided for provost tribunals to try military personnel accused of offenses against military law. Originally, the procedures for courts-martial were inefficient, but an attempt to correct deficiencies was effected a year and a half later, in October 1862, authorizing a military court for each army corps in the field to exercise unrestricted jurisdiction over military personnel and civil jurisdiction in occupied areas. Each court was permitted to appoint a provost marshal with the rank and pay of a captain of cavalry to execute its orders, and provost jurisdiction was extended to include offenses against the Articles of War, Confederate law, and state law. General courts-martial were also established and they had their own appointed regimental officers serving as provost marshals with duties similar to those of a sheriff in a civilian court.

Although the Articles of War were intended to provide for the trial of military offenders against military law, imprecise wording could be construed as making civilians answerable to military courts. The standards of discipline of the marshals and their subordinate officers, and the degree to which “inhumanity would be tolerated in the imposition of discipline,” varied. Problems frequently arose between the provost marshals and various state supreme courts (acting on writs of habeas corpus) concerning the jurisdiction of the military over civilians accused of crimes against the Confederacy. In one instance, Louisianans loudly bemoaned limited efforts to suspend the writ, and citizens protested the suspension of such rights in New Orleans immediately prior to the Union occupation. When Winder put Richmond under martial law, his undiplomatic methods caused further repercussions. Alarmed, the Confederate Congress quashed Jefferson Davis’s authority to suspend habeas corpus, and virtually anything that smacked of a threat to states’ rights was strenuously resisted.

“Evildoers Were the Only Ones the Police Did Not Trouble”

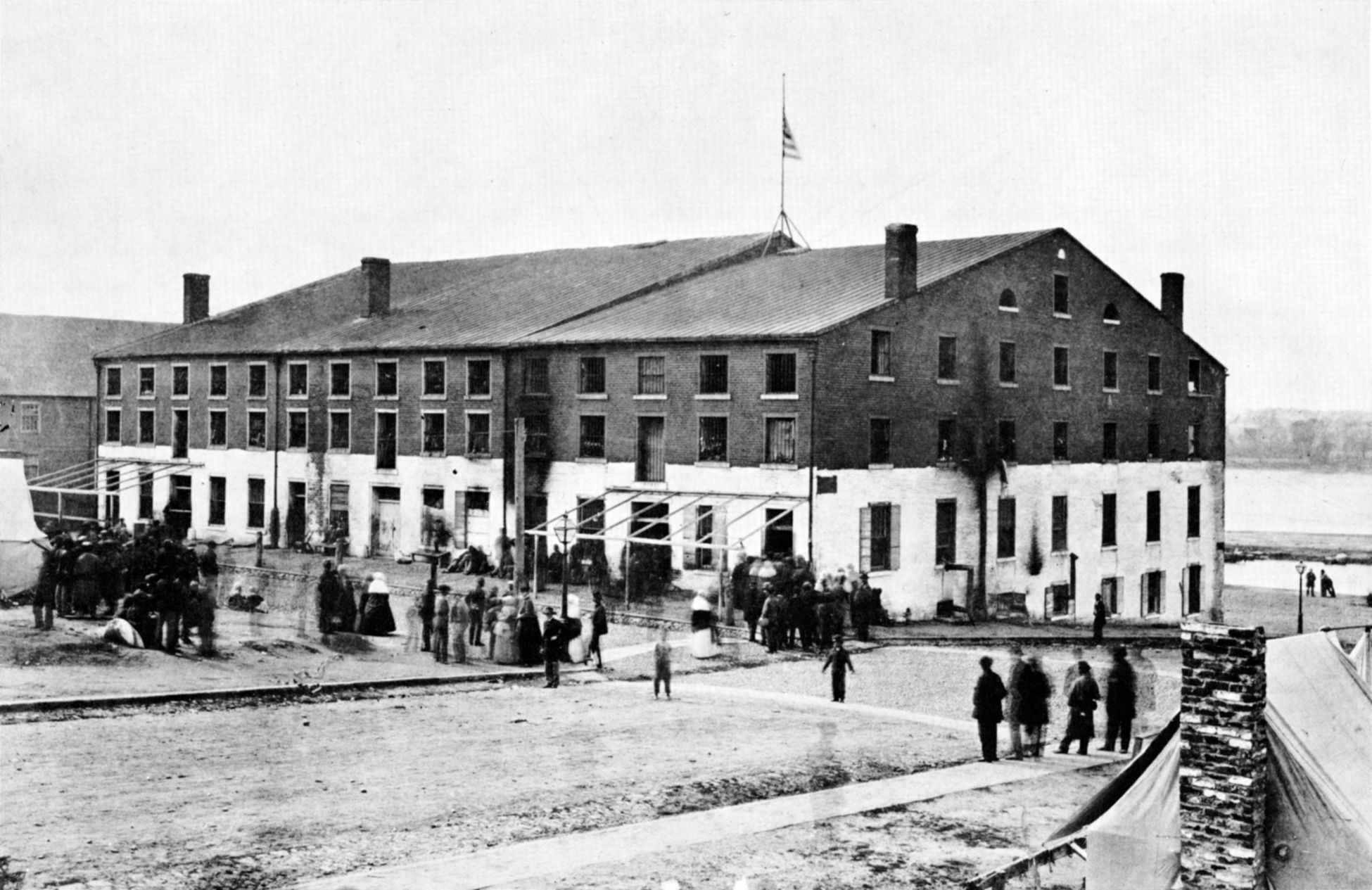

Provost responsibility extended to the operation of detention facilities and service prisons, with Winder tasked with their administration. Initially appointed inspector general of all camps, including the prisons in the Richmond area, Winder met with constant disapproval from the majority of Richmond civilians, who considered the general “active but outrageous.” Said one disgusted citizen, “Evildoers were the only ones the police did not trouble. [They were] oppressive only to the peaceful.”

Unceasing efforts to control desertion occupied more and more provost troops as the Confederacy’s fortunes deteriorated. Large areas in western North Carolina’s rugged Sauratown Mountains and parts of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi became sanctuaries for huge numbers of deserters. Constant appeals to deserters to rejoin the colors fell on deaf ears, in many cases not due to cowardice but to increasing concerns for and acute anxiety over the welfare of their families in the war-ravaged South. In numerous dispatches from November 1864 to March 1865, Lee’s message on desertion was virtually the same: “Hundreds of men are deserting nightly. I do not know what can be done to put a stop to it.”

The decline in confidence and morale significantly decreased the chances of Confederate victory. It is perhaps telling that one of the last operational tasks performed by the provost guard occurred during the evacuation of Richmond in April 1865, exactly seven days before Lee’s surrender to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox. A local defense brigade officer was charged with defending the last bridge over the James River east of the city as the remaining provost troops withdrew. As the last of the cavalry crossed the bridge and an engineer officer set it afire, one of the retreating cavalrymen exclaimed, “All over, goodbye; blow her to hell.” It seemed fitting that a provost guard should have been among the last to leave the burning capital, serving as the rear guard of a nation also blown to hell.

“It seemed fitting that a provost guard should have been among the last to leave the burning capital, serving as the rear guard of a nation also blown to hell.”

That about sums it up!