By Eric Niderost

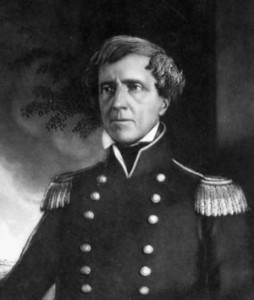

Around noon on September 25, 1846, Brig. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny mounted his bay horse and raised a hand in salute. He was an impressive figure, ramrod straight in the saddle, impeccably dressed with a double row of brass buttons marching down his chest and gold epaulettes perched on each shoulder. At Kearny’s signal, his grandly named Army of the West moved out of Fort Marcy, a military post just outside Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Beginning a Daunting Task

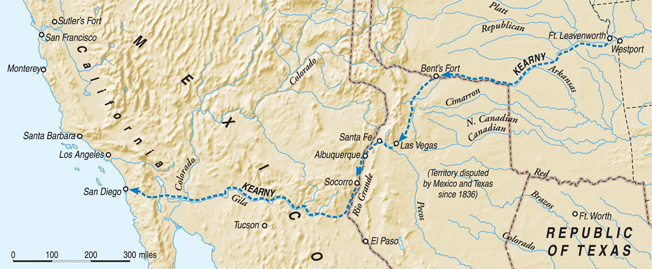

Kearny, a professional soldier, had been given a vitally important assignment. The newly minted general was ordered to take over New Mexico, then proceed to California and establish a functioning American government there. The odyssey actually began weeks earlier at Fort Leavenworth, on the Kansas plains, where the 1,700-man army assembled for duty. Many of the troops were hastily raised civilians, such as Colonel Alexander Doniphan’s Missouri Mounted Volunteers, but the Army of the West’s professional core was provided by Companies B,C, G, I, and K of the U.S. 1st Dragoons.

The journey from Fort Leavenworth to Santa Fe had been no picnic, but the men were inured to hardships on campaign. Kearny was a strict disciplinarian who forced a grueling pace—22 miles a day was average, and sometimes the column exceeded 30. The troopers longed for action, but the Mexicans seemingly refused to cooperate. Most Americans of the time viewed Mexicans with contempt, considering them culturally and biologically inferior to whites. The Army of the West’s first encounters with Mexican people only fed these stereotypes. The column met a few Hispanics along the trail, seedy-looking individuals mounted on diminutive jackasses. Lieutenant William Hensley Emory later recalled that the Mexicans presented “a ludicrous contrast by the side of the big men and horses of the first dragoon[s].” Even mountain man guide Tom Fitzpatrick, who had a notable sense of humor, convulsed with laughter at the poorly mounted Mexicans.

A Phantom Enemy

The army’s overconfidence was soon replaced by mounting frustration. The men entered Las Vegas, New Mexico, without opposition, but rumors arose of a large Mexican force waiting just outside town. Here was a chance for glory, a chance to forget the short rations and endless hours in the saddle. The national and regimental colors were unfurled, and each company’s fork-tailed guidons waved in the breeze as buglers sounded commands, the brassy notes galvanizing the men and exciting their horses.

The Mexicans were supposed to be hiding in a gorge two miles from Las Vegas, and as the troopers neared the gorge, the squadrons broke into a full-blown charge. The troopers were quickly disappointed—they found the gorge discouragingly empty of the enemy. The Mexicans had fled if, indeed, there had ever been any Mexican soldiers in the vicinity in the first place. Emory, a topographical engineer with a keen eye for terrain, noted that there were several potential defensive positions along the Americans’ line of march. They had been left unmanned. The Mexicans seemed unwilling or unable to mount any kind of defense.

A Bloodless Victory

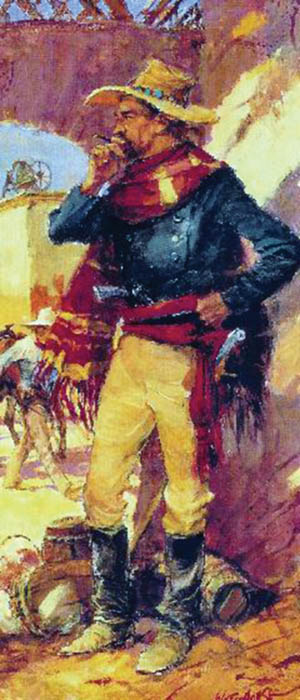

Don Manuel Armijo, the governor of the New Mexico province, was a self-styled general with no actual military experience. In fact, he preferred bombast to bullets, regularly unleashing a steady stream of paper proclamations and bellicose speeches on his unfortunate subjects. A comic-opera stereotype, the portly Armijo stuffed himself into a gaudy uniform dripping with gold lace, but there was no substance beneath the grandiose façade. He realized his bluff was about to be called.

Apache Canyon, a narrow defile 15 miles southeast of Santa Fe, was the last best place to stop the norteamericano invaders. Armijo hastily assembled some 3,000 local inhabitants, urging them to “crush the gringo invaders.” It was a ragtag army scarcely worthy of the name, a hodgepodge of peon farmers, ranch hands, sheepherders, and old men armed with weapons so antique they belonged in a museum, not on a battlefield.

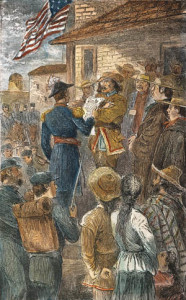

Luckily for all concerned, Armijo fled the scene and his army melted away like snow in the desert sun. American forces occupied Santa Fe without firing a shot—except for the 13-gun artillery salute that accompanied the raising of the Stars and Stripes on the roof of the governor’s palace. Kearny, for his part, was conciliatory but firm. He made a speech that declared New Mexico part of the United States. Its citizens—at least the prominent ones—would have to declare allegiance to the American government. Mexican institutions such as the Catholic Church would be respected, and the American army would protect the people of New Mexico from marauding Indians.

Onward to California

Kearny stayed in Santa Fe for a month, laying the foundations of American control, before pushing on to California, the main goal of his peripatetic mission. California, three years’ shy of its epochal gold rush, was still a much-sought-after prize. Its mineral riches were as yet untapped, but all recognized its natural bounty in the form of a mild climate, rich topsoil, and long coastline indented by good natural harbors. Mexican California was largely confined to the coast, a thin veneer of Hispanic civilization anchored by a chain of 21 Catholic missions. The missions had originally been meant as temporary institutions, lasting no more than a decade, but they had ossified into a kind of permanent status. They had been secularized in the 1830s, shut down, and acquired by a rising class of local cattle barons called rancheros. In 1846, Mexican California had around 7,000 Hispanics and one-tenth as many Americans. This figure did not include 6,000 former Mission Indians and well over 100,000 Native Americans living in the interior.

The Californios

California, for all its promise, was still some 2,000 miles away from the leading politicians and generals in Mexico City. The native Hispanics—called Californios—had grown bitter over time at Mexico City’s neglect. The bitterness festered until some prominent Californios began to think openly that the sore could be cured only by the balm of semi-independence. A few even dared to think of foreign intervention—perhaps an American protectorate or even annexation.

The last outside governor of California—that is, one from Mexico—was General Manuel Micheltorena. He was not without talent, but the 300 soldiers he brought with him proved to be his undoing. They were an ill-disciplined lot, ragged and semi-mutinous; many were ex-convicts. When regular pay was not forthcoming—a common complaint in early California—many soldados simply went back to their old light-fingered trades. Their numerous thefts and outrages alienated the Californios, who rose in revolt, and before long Micheltorena and his band of robbers were expelled from the province.

The Californios had triumphed temporarily, but they were divided into northern and southern factions. Governor Pio Pico, a native Californian, became governor of the rebellious but essentially autonomous province. He was the head of the southern faction, with his capital in the tiny pueblo of Los Angeles. The north was controlled by Jose Castro, military commandant of the region. Don Jose’s base was Monterey, the principal port of California, and he financed his power with revenue from the all-important customs house.

Local Support for Annexation

The Californios still gave lip service to Mexico, but by 1846 they were effectively independent of Mexican control. At the same time, California was dependent on foreign trade, which had kept the region prosperous during its long periods of official neglect. The rancheros thrived on a growing tallow and cattle-hide industry. Americans and British dominated the hide and tallow trade through strong ties with the burgeoning factories of New England.

Californio leaders such as General Guadalupe Vallejo of Sonoma liked the Americans and favored annexation. These sentiments were encouraged by U.S. Consul Thomas Larkin, a Monterey businessman who doubled as a diplomat. Larkin himself was well respected by the Californios and had a great deal of personal and political influence. The consul worked feverishly for American annexation, at one point exulting in a private letter that “the pear is near ripe for falling.”

The Long Trek

Kearny had been ordered to complete the California harvest by occupying the territory and establishing a functioning American government there. With New Mexico apparently pacified, he looked forward to continuing on to the Pacific Coast. To date, the Army of the West had traveled some 850 miles from Fort Leavenworth to Santa Fe. Now it was about to embark on the most difficult and physically demanding leg of the journey.

In leaving Santa Fe, the Americans in effect were leaving the last vestige of civilization. Captain Philip St. George Cooke noted that “tomorrow, three hundred wilderness-worn dragoons, in shabby and patched clothing set forth to conquer or annex a Pacific empire, to take a leap in the dark of a thousand miles of wild plains and mountains.” Cooke, not one for hyperbole, worried that they would be crossing several deserts where “a camel might starve, if not perish from thirst.” Events would soon prove Cooke too sanguine in his worries.

The expedition was meant to gather information as well as to conquer. Emory headed a 14-man topographical party attached to the Army of the West. He was a consummate professional, eager to gather data that could be used to create the first accurate map of the lower Rio Grande-Gila River region. To do so, he was equipped with a special instrument wagon filled with chronometers and barometers. The first few days, as the column marched down the Rio Grande valley, were deceptively pleasant, warmed by the late fall sun. Vast groves of cottonwoods and willows lined the river. On October 6, the Army of the West camped at Valverde, where ruins bore mute testimony to Spain’s ultimate failure to halt Navajo and Apache Indian raids.

A Surprising Rendezvous

About noon, a small party of horsemen was spotted heading toward the camp. There was a moment of anxiety—were they hostile Indians? Tensions eased when it was discovered that most were white men, headed by Christopher “Kit” Carson, one of the most famous mountain men of his era. Carson was bound for the East Coast, carrying dispatches from Commodore Robert Stockton to President James K. Polk announcing the peaceful occupation of California.

Kearny was thunderstuck—had his mission been preempted? He pored over the dispatches, and Carson provided additional information. Elements of the U.S. Pacific squadron had landed three months earlier, boldly proclaiming that California was now part of the United States. On July 7, a party of American marines had marched to the Monterey customs house and raised the Stars and Stripes. Two days later, Captain John B. Montgomery of the USS Portsmouth landed at the village of Yerba Buena (later San Francisco) and raised the flag there as well. The Californios seemed indifferent to the American takeover. Some, like Vallejo, actually welcomed the change of regimes.

Kearny was not one to hesitate, and after short reflection he decided to press on to California. Orders were orders, even if the Navy had stolen his thunder. Knowing that they would soon be leaving the relatively benign Rio Grande valley and heading west toward the forbidding Gila River region, Kearny ordered Carson to abandon his original mission and guide the army to California. On Carson’s advice, Kearny sent 200 dragoons—two-thirds of his force—back to Santa Fe. He would soon regret his hasty decision.

Encounters with Native Tribes

The column struck westward into the sandy upper reaches of the Sonoran Desert. The wagons quickly got stuck in the sand, as Carson had warned, driving the mule teams to exhaustion. Progress was so laborious that Kearny finally ordered the wagons to be abandoned. Supplies were switched to pack mule, something that filled Emory with dismay since his delicate instruments were not designed to be carried in such rough fashion.

The line of march followed the meandering Gila River. The days were blisteringly hot; the nights freezing cold. Cactus sprouted everywhere, the sharp thorns ripping sweat-stained blue uniforms to shreds and lacerating the sides of the long-suffering horses and mules. Soon, all the animals were scarred with cactus wounds and saddle sores, and the cavalry horses that were the source of so much pride to the troopers began dying in droves, leaving many of the men to stumble on foot. Kearny’s own mount, a magnificent bay, died and was left for the coyotes and vultures. Kearny had to switch to a mule, which might have looked ridiculous but at least was better than going on foot.

In spite of the hardships, Kearny managed to meet with some Indians along the way, including the Apache leader Mangas Coloradas, father-in-law of the great future chief, Cochise. The Apaches recognized at once that these white men were different from the Mexicans and quickly swore eternal friendship with the newcomers. (Carson wryly observed that he would not trust any of them.) The column also passed through the lands of the Pima and Maricopa tribes, gifted agriculturalists who made the desert bloom with wheat, corn, and other crops. Emory, a keen observer, noted that the Indians were peace loving yet obviously able to defend themselves against Apache depredations.

A Change in Circumstances

It was now November, and the Americans captured a Mexican courier in possession of important dispatches. The papers, dated October 15, told of major Californio uprisings against the Americans in Los Angeles and Santa Barbara. This altered the strategic picture and galvanized Kearny’s entire command. They could expect hard fighting—and soon.

The Army of the West crossed the Colorado River into California on November 25. The next few days were ones of incredible hardship for the Americans as they crossed a 90-mile stretch of barren landscape. The brackish water available did little to quench the raging thirst of men and beasts. Food was so scarce that the troopers had to slaughter their mules. Their immediate goal was Warner’s Ranch, near the base of the southern Sierra Nevada. As they neared the ranch the land became richer, blessed with rich soil, waving grass, and stands of mighty oaks. Warner’s Ranch seemed like the Garden of Eden to the travel-worn command, and they spent two days resting and feasting on mutton. Although somewhat refreshed, the dragoons were still a sorry sight: emaciated, ragged, sunburned, and half naked. Some were even barefoot.

The troopers managed to round up 75 fresh horses and mules, although only 30 were saddle broken enough to be of service. They belonged to Jose Maria Flores, a leading insurgent against the Americans. One of his drovers reported the theft and told Flores that there was a group of gringo soldiers in the area. Thus alerted, Flores contacted Major Andres Pico, brother of the governor, and advised the officer to reconnoiter the area. In the meantime, Kearny dispatched a message to the American forces at San Diego, urgently requesting an escort to the coast. When Commodore Stockton received the missive he immediately ordered Marine Captain Archibald Gillespie, Lieutenant Edward Beale, and friendly Californio leader Rafael Machado to take a small force and link up with the Army of the West. Gillespie’s mixed command took along a four-pounder cannon as artillery.

Altogether, Gillespie brought another 37 men to Kearny’s command, boosting the totals to roughly 140. Kearny also had two artillery pieces of his own, dragged laboriously though the sandy wastes and mountain defiles. The general was happy to see Gillespie, but he keenly missed the 200 extra men he had sent back to Santa Fe. Ironically, Gillespie was one of the reasons the Californios were in revolt in the first place. His high-handed occupation of Los Angeles, including arbitrary arrests, had caused much bitterness among the local population.

Clumsy Scouting

On December 5, Don Andres Pico arrived at San Pasqual, a small Indian village 30 miles east of San Diego. Don Andres, supposedly a competent soldier, was apparently unaware the Americans were camped only six miles away. He had around 80 men, mostly local vaqueros, under his command, and at first glance the Mexicans seemed outmatched. For the most part, his men were not professional soldiers, and they possessed few firearms. But the disparity was more apparent than real. The Californios were armed with lances, and they knew how to use them. By contrast, the Army of the West was a mere shadow of its former self, the troopers no more than emaciated scarecrows mounted on mules or half-broken horses.

The night of December 5-6 was cold and rainy, dampening American spirits as well as drenching the troopers’ ragged uniforms. Gillespie warned Kearny that there were Californio soldiers in the vicinity and offered to send some of his own mountain men to scout the area. Kearny approved the idea but preferred to send his own dragoons to reconnoiter. Events would prove that this was a crucial tactical blunder.

Lieutenant Thomas Hammond was ordered to lead the scouting party, accompanied by Californio turncoat Rafael Machado and six dragoons. The lieutenant and his party rode within a half mile of San Pasqual, then quietly dismounted. Machado crawled toward the village while Hammond and the dragoons stayed behind. It was a slow and painstaking process, but Machado managed to sneak into San Pasqual without detection and talk to an Indian villager, who was more than happy to give him information on Pico’s forces. The natives feared and hated Don Andres and his lancers. Meanwhile, Hammond grew tired of waiting in the cold, clammy darkness. He mounted his horse, the other six dragons following suit.

Incredibly, Hammond and his party rode directly toward San Pasqual, sabers and scabbards rattling noisily as they approached. Village dogs let out howls of alarm, the canine chorus blending with human shouts of alarm. The Californios emerged from the Indian huts and raced to their horses, crying: “Viva California! Abajo los Americanos!” Hammond and his men managed to locate Machado in the confusion, and the whole scouting party beat a hasty and undignified retreat. One Californio found a blue army jacket that had been lost by one of Hammond’s troopers. Pico examined the garment and noted the initials “U.S.” on it. Here was proof, if any were needed, that Americans were indeed in the vicinity.

The scouting party returned to camp just past midnight. After listening to Hammond’s report, Kearny issued orders for an immediate attack. There was no alternative. The coming daylight might reveal to the Californios just how exhausted and vulnerable the Americans really were.

“Oh, heavens!” A Mistaken Charge

The Army of the West was in the saddle by around 2 am. It was bitterly cold, and a bugler tried and failed to nurse a few frozen notes from his instrument. The troopers moved out in a column of twos, every man eager to finally come to grips with the enemy. Kearny led his men to the brow of a ridge just outside San Pasqual valley. The general said that he wanted merely to capture fresh mounts, and that he wanted to keep casualties—including Mexican casualties—to a minimum. This was not to be a wholesale slaughter. How much this advice registered with the men is unknown. Most of the soldiers simply wanted some action after a grueling yet uneventful trek.

His speech concluded, Kearny led the descent to the valley floor. He ordered Captain Benjamin Moore to spearhead the attack and encircle San Pasqual. Captain Abraham Johnston would follow in close support, his men mounted on the best horses or mules the Army of the West could muster, to provide the muscle in the operation, completing the encirclement and making sure no one escaped.

Kearny was in the vanguard, accompanied by Lieutenant Emory and the redoubtable Carson. Gillespie’s men and the artillery brought up the rear. Kearny shouted the command, “Trot!” But in the excitement Johnston thought he heard the word “Charge!” instead. He acted accordingly. Johnston drew his saber, dug into his mount’s flanks, and repeated the order “Charge!” to his men. They were off in an instant, and since Johnston’s group had the best horses, they soon outdistanced the rest of the command.

“Oh, heavens!” Kearny exclaimed when he saw what was happening. “I did not mean that!” By now Johnston’s men were well beyond earshot and hell-bent for leather. Pico had ordered his men to fire their muskets before engaging the Americanos, and Johnston’s galloping troopers were met with a ragged volley. One lucky shot crashed into Johnston’s forehead, killing him instantly. Another trooper went down, and the remainder found themselves hard-pressed by lance-wielding Californios.

Just when all seemed lost, the Californios abruptly broke off the attack and turned tail. The reason soon became apparent—Moore and his 50 troopers had arrived on the scene. Moore and his men gave chase for about a mile, but in doing so the dragoons became dangerously strung out. Weary mules and jaded, half-broken horses could not keep the pace. Even Kearny’s mule was giving out, and he was falling farther and farther behind.

The Retreating Californios Turn About

The Californios suddenly drew rein and wheeled about, facing their enemies. The tables were turned—the pursued were about to become the pursuers. The American dragoons were suddenly confronted by a line of horsemen coming at them at full speed, their eight-foot lances resting menacingly under their arms. As soon as the two groups collided it was clear that the Californios had the advantage. Their horses were fresh, and they maneuvered their mounts so well that animals and riders seemed as one. Kearny marveled at the enemy’s superb horsemanship

Moore dueled with Major Pico himself, and the two furiously traded sword blows. Pico parried Moore’s thrusts and slashed him with his own blade. Two lancers rushed to the aid of their commander, spearing the hapless American officer again and again until he finally tumbled from the saddle, mortally wounded. Moore lay near an oak tree, his uniform drenched in blood, still clutching the hilt of his broken sword. A Californio came over and finished off the captain with a well-aimed pistol shot. Moore’s brother-in-law, Lieutenant Hammond, attempted to ride to his aid and was fatally stabbed by Californio lancers for his trouble.

Kit Carson was unhorsed when his mount lost its footing. Winded but otherwise unhurt, the famous scout had only seconds to react to a new danger. He was directly in the path of some on-charging dragoons, and as he later admitted, “I came very near being trodden to death.” Carson managed to scuttle away, but his gun was broken. He could see that the Americans—including himself—were no match for the Californios on horseback. He quickly found a discarded rifle and hurried over to a cluster of boulders. Once ensconced in his natural fort, Carson began to pick off any lancers that came within range.

A Pyrrhic Victory for the Army of the West

Kearny himself was badly wounded when an enemy lance thrust drove deep into his back and entered his buttock. Unhorsed and bleeding, Kearny could do little to rally his rapidly disintegrating command. Within minutes, the Californios made short work of the American dragoons. The troopers fought with clubbed carbines and sabers, but the contest was unequal from the start. Particularly unnerving to the Americans was the way the Californios worked efficiently in teams. One vaquero would rope a dragoon from the saddle with an effortless yank. Once on the ground, the helpless trooper, hog-tied by a reata, would be impaled on a second vaquero’s lance.

Gillespie was singled out as a special target of Californio ire. His heavy-handed rule of Los Angeles had started the revolt in the first place. Gillespie was lanced several times but managed to avoid a fatal thrust. Bloodied but defiant, Gillespie managed to find his way to one of the artillery pieces. Aided by a midshipman named James Duncan, he fired off a round or two of grapeshot that effectively broke up the Californio attack. The lancers left the field, enabling the Americans to technically claim a victory, albeit a mostly Pyrrhic one. Three officers and 21 men were dead, and another 17 were wounded.

The decimated Army of the West limped forward cautiously; it was clear the Californios were still in the vicinity. Kearny felt his men could do no more. It was better to dig in and send for relief. The general chose to make a stand on a small boulder-choked rise that was studded with cactus. It was less than ideal, but at least it was high ground. The dragoons threw together some rough fortifications, then settled in to wait for reinforcements. The nearest help was the U.S. Navy force in San Diego, 30 miles away. With the quick-riding Californios infesting the area, it might as well have been 100.

The Rescue

Carson, Lieutenant Edward Beale, and a Diegueno Indian named Chemuctah were chosen to sneak through enemy lines and bring aid. The trio set out on the night of December 8. The ground was rough and gravelly, so Carson and Beale removed their boots to make less noise during their descent. Chemuctah’s soft moccasins were not a problem. The night was still, and Carson worried that their canteens would make too much noise, so reluctantly they left them behind.

The first obstacle was a line of Californio pickets mounted on horseback and armed with lances. Carson, Beale, and Chemuctah crawled under the very noses of the pickets, close enough to the enemy horses to smell them. Somehow, Carson and his companions managed to evade detection, but Carson and Beale lost their boots in the darkness. There was no time to search for their lost footwear. They continued through rugged canyons and cactus-dotted arroyos until they cleared Pico’s pickets. By mid-morning, Carson and Beale were in bad shape, their feet lacerated by rough rocks and cactus spines. Californios still swarmed through the area, so the three messengers split up. That way, there was a chance one of them would get through.

Carson literally stumbled into Stockton’s camp in San Diego at 3 am, some 12 hours after he had said good-bye to his companions. To his surprise and relief, he found that both Beale and Chemuctah had gotten there ahead of him, having traveled in a straighter line. A relief column of some 200 men had already been dispatched to Kearny’s aid.

The rescue force reached Kearny and the battered Army of the West two days later and drove off the besieging Californios. The painfully wounded general finally made it to San Diego, claiming a technical victory at San Pasqual but admitting that “we paid most dearly for it.” Emory the scientist noted precisely in his records that the army had traveled 1,912 miles from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to San Diego. It was one of the greatest forced marches in American military history. Unfortunately, the trek brought Kearny’s men crashing headlong into Don Andres Pico and his determined Californios, who made good their boast: “Aqui vamos hacer matanza [Here we are going to have a slaughter].” It was all that and more.

Originally Published February 2010

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments