By Marcus Brotherton

“The true picture of war is impossible to convey—even by those who did the bleeding and the fighting.”

So wrote Burton “Pat” Christenson at the start of a pictorial journal he made for his three sons after the war. The journal is the size of a large picture album and runs more than 50 pages. Inside are pictures drawn by Pat––exquisitely detailed pencil sketches of the war he lived through. Underneath each drawing is an excerpt from a journal he kept about his season of fighting in Europe. Sometimes the journal excerpts show straight descriptions of battle scenes; sometimes they are poems or analyses. The art flows from him in various forms as he’s ever seeking to communicate his experiences.

Pat’s art is graphic, vivid, not something you’d show to a six-year-old. One page shows a soldier clutching his hand over one eye. The soldier has just been hit by shrapnel. Blood gushes from his hand and spills over his face. The soldier’s other eye is still open, shocked, looking straight ahead. “Only those who were wounded severely know the conflicting emotions and anxieties that race through a person’s brain,” wrote Pat underneath, “if one is still conscious after being hit.”

Pat also left an additional journal, the thickness of a small phone book. He wrote in pencil, sometimes printing the words, sometimes writing in large, clear cursive. The journal begins August 12, 1942, and talks about why and how he joined the Army. It ends in 1945, in Saalfelden, Austria, during occupation duties at the end of the war. Much of the journal appears to be reconstructed in later years from recollections, notes, and conversations with other E Company men.

Inside the journal are detailed descriptions of army life and combat, including references to maps and separate essays about everything from what it’s like to have flat feet from the long marches while carrying heavy equipment (“Sheer torture. My arches were gone. I found a podiatrist who sold me a pair of steel arch supports.”), to a probing query about motivations for war (“What are we fighting for? Very few men in combat mention patriotic motives. Thoughts of making it through the war and going home are foremost in their minds.”).

The two journals, together with his drawings, leave one of the most complete eyewitness accounts of life in Easy Company, 506th PIR. What follows is the story of Burton “Pat” Christenson.

Burton “Pat” Christenson was born in Oakland, California, on August 24, 1922. Few people ever called him Burton. Most of his friends either called him Pat, a nickname he gave himself, or Chris, the shortened form of his last name. His middle name was Paul, so Pat may have been a derivative of that. Family members knew him as Pat. Sometimes he signed letters as Chris.

As a child, he was driven to create. He never studied art professionally except for a few classes during one semester of college, and never worked at art as his career, but it remained a lifelong passion. The gifted boy could draw, play piano, and sing—talents he nurtured his whole life.

Well into his seventies, he invited fellow Easy Company members over to his house, including Bill Guarnere, Bob Rader, Tony Garcia, Bill Wingett, Woodrow Robbins, and Mike Ranney, and “they chased the ghosts of the war together,” said one of his sons, Chris. During these impromptu get-togethers, Pat played the piano, the men sang songs from the 1940s, and they drank. “The men were never shy about drinking,” Chris added.

While in the service, Pat and fellow Easy Company members PFC Carl Sawosko and PFC Coburn Johnson sang together with a guitar. Johnson was wounded during the Normandy campaign and sent home. Sawosko was shot in the head in Bastogne and died. Pat described losing his friend Carl as one of his greatest losses.

Pat’s nephew, Gary Van Linge, 13 years younger, lived just down the street from Pat. “He was always my hero,” said Gary. Before the war, Pat took up archery after watching the movie Robin Hood, starring Errol Flynn. Gary contracted scarlet fever at age seven and was quite sick for some time. The young boy had a thick book about Robin Hood, and Uncle Pat frequently came to the house and read to the child. “I’ve been involved in archery ever since,” Gary said.

Pat was a creative teen. He made airplane models out of balsa wood kits. Paper was stretched over the wood and glued, then water flicked on the paper to tighten it up. Pat was a master at it, a real artist, noted Gary. The models flew with propellers and rubber bands, and if Pat made a model that wasn’t perfect, he lit it on fire and flew it that way.

Pat could be adventuresome. At age 13 he jumped off the roof of his house with a large beach umbrella to see if it would break his fall. “I don’t know how much it actually slowed his descent,” Gary said, “because he never did that again.”

Pat was always athletic and physically strong. He made his own set of weights by pouring lead into flowerpots and sticking pipes in the ends. He was always doing pushups. “He could walk on his hands like nobody I’ve ever seen,” Gary said. “He could walk a hundred yards on his hands, no problem. He was a natural when it came to going into the Airborne.”

Pat taught Gary how to box and made him fight every kid in the neighborhood. It was more a sporting event than malicious fighting, and everybody participated. “All the kids in the neighborhood loved him,” Gary said, “especially when he became a paratrooper. He was a hero to us kids.”

He graduated from Castlemont, a big high school in Oakland, California, then worked for the Pacific Telephone company for a short time before the war. He enlisted at age twenty. “He wanted to serve his nation,” Chris said, “and I think he wanted the challenge. My dad was a very competitive man.”

Pat’s journals concur. He described how he and a friend from work talked constantly about “getting into the fighting part of the war.” They went to an Army recruiter’s office during their lunch break at the phone company where they saw a brochure for the Airborne that read, “Jump to the Fight.”

They were convinced the paratroopers were the only way to go.

After enlisting, Pat was sent to Toccoa, Georgia, where he wrote that, at first, “the majority of men had little conception of Army life and what was expected of them.” Mostly, “too many men in our ranks were unsuited for the Parachute Infantry,” which prompted heavy washouts. Over time, cohesiveness formed in the unit as the men hardened into soldiers.

“Pat became a paratrooper because he wanted to be the best,” Chris said. “He didn’t just want to be the average ground-pounding grunt, not to take away from that, but he wanted to be in a special unit.”

Pat held the physical-fitness record at Toccoa. That’s stiff competition—to be the toughest man at Toccoa. The family has a letter from company commander Dick Winters verifying this. In Band of Brothers, the HBO series shows Pat being the goat of training, drinking water on a run when he wasn’t supposed to and having to run up and down Mount Currahee again. “We’ve asked the men who were there if that ever happened,” Gary noted. “They said, ‘Not to Christenson.’ ”

His young nephew kept a close watch on Pat’s experiences from basic training onward. When Pat was in jump school, he taped his nephew’s picture inside his helmet while making his five qualifying jumps, then commandeered an extra set of jump wings, which he sent home to Gary. “He told me I was a qualified jumper,” Gary said. “With those wings I was the envy of my school. In those days, everybody was well into the war effort. The armed forces were honored by teachers and students alike.”

In spite of the rigorous training, Pat kept a rueful sense of humor. After the unit was sent to Alderbourne, England, for further training, he wrote, “Our training revolved around how to fight every conceivable way, and often, large groups of men gathered at the local pub.” He described the food they ate in England—Brussels sprouts, turnips, and “I think they slipped some horse meat to us from time to time.”

Headquarters staff expected an enemy invasion on England’s airfields, so Lieutenant Winters picked three E Company men to teach unarmed combat to nearby defense units. Pat and the others selected were only privates, so Winters told them to borrow shirts from fellow sergeants in case they were challenged by the trainees. The three E Company men traveled to a nearby air base and taught the defense unit hand-to-hand combat techniques for several days. It was a rough-and-tumble crew, but Pat didn’t back down. He wrote: “After a period of time, a group came to me and exclaimed, ‘Sergeant, no one can get out of this guy’s hold. If this stuff works, show us how you’d get away from him.’ There, standing in the middle of the group, was a great big 300-pounder with a smile from ear to ear.

“I deliberately paused, directed a cold stare at him, then approached quickly and said, ‘Make your move.’ As soon as I felt his arms around me I immediately collapsed my legs and threw my arms over my head. I slipped out of his grasp and found the back of his neck with my hands. His body was now bent over my back. I jerked hard on the back of his neck. His body, off balance, came flying over my shoulder and struck the ground with a violent thud. Swiftly, I drove my knee into his neck. I had never executed that move as well before or since.

“The crowd roared with approval. Then and there, to that group, I was untouchable.”

The company moved to a marshalling area near Exeter, England, then to Uppottery Airfield in preparation for the D-day invasion. Pat described flying over to Normandy on the night of June 5, 1944: “The aircraft moved along at a smooth pace. The only noise heard was the drone of the engines.”

He was in the same plane as Lieutenant Winters, who stood in the door, watching the approaching coast of France get larger. Pat was second in line to go out the door behind Winters. Everything was quiet for some time, then a few miles into the peninsula, Winters pointed to the aircraft ahead and said, “Look, Chris, they’re catching hell up ahead of us.”

Pat wrote: “The red and orange tracers were reaching for the forward aircraft. Tension began to mount, nerves became taut. A burst of flak to our right aroused those still mesmerized by the long flight. [We were] conscious now that our drop zone couldn’t be too far away.

“The flak grew heavier. We stood now, ready to get the hell out of that bobbing and weaving C-47, the pilot doing his damndest to elude the fire. Antiaircraft now hammered incessantly. It was time to go. On went the green light. Go-go-go!

“As Winters left the plane, a heavy burst of 20 mm hit the tail of the plane. I thought for certain he had gone right into it. I was out the door behind him in another second.”

The shock of the opening blast tore much of the gear from Pat, as it did with many of the men that night. The pilots were flying too fast and too low. Pat was a machine gunner and carried a machine-gun tripod, which he lost, along with his carbine, his ammunition, and musette bag.

“During the descent, a machine gun traversed the 18 men in my stick with long bursts of fire. Adrenaline pumped through my body. Explosions filled the air. A C-47’s engine was on fire, about 150 feet off to my right. [The plane] seemed to be disintegrating.

“A bell was ringing in a town off to my left. I thought, ‘Keep your composure, assess your situation, plan your moves quickly. Christ, I’m headed for that line of trees. I’m descending too rapidly. Concentrate on your landing.’

“I could see an orchard beyond the trees. As I passed over the trees I drew my legs up to avoid hitting them. A moment of terror seized me: 70 feet below and 20 feet to my left was a German quad-mounted 20 mm antiaircraft gun. That moment it opened up, firing at the C-47s passing above.”

Luckily, the Germans were concentrating on shooting someone else and didn’t look and see Pat. “It was really fortunate,” the paratrooper told his nephew later, “because they would have given me a burst, and that would have been it.”

It wasn’t until years later when Pat watched the movie The Longest Day that he understood what the ringing bell he had heard was all about. He was near the town of Ste. Mere-Église when he jumped, and had always speculated the Germans were ringing the bell as an alarm. Actually, it was the townspeople ringing the bell because a house near their church was on fire.

Pat landed high in an apple tree and crashed down the trunk. He found himself in an apple orchard, his only weapon a .45-caliber revolver he had bought from a British paratrooper for fifty bucks. He carried that .45 throughout the rest of the war. He jumped into a hedgerow for cover and stepped on a dead American pathfinder, a large blond man.

“It scared the hell out of him,” Gary noted, “because the dead guy let out a grunt as the air escaped from his diaphragm.” It was a gruesome start to the war. The night’s adventures were just beginning.

Pat wrote: “I remained quiet and still, moving only my head. Suddenly my eyes caught movement 40 feet in front of me. A silhouette of a helmeted man approached me on all fours. I reached for my cricket and clicked it once, click-clack, the sign of a friend. The figure stopped. I waited for the counter sign. There was no response.

“The silhouetted figure began to move toward me again. My handgun pointed in the center of his chest. I again gave him the click-clack. He immediately responded with a hand raised: ‘For Christ-sake, don’t shoot.’

“Immediately I knew it wasn’t a German. It was my assistant gunner, Woodrow Robbins. ‘What the hell’s wrong with you?’ I asked. ‘Why didn’t you use your cricket?’ ‘I lost the cricket part of the cricket,’ came his stammering reply (the sound-producing part of the device).

It was then about 1:50 am.

Pat soon picked up a German Mauser, model 98, a bolt-action rifle, which he used for the first few days of the Normandy campaign, then picked up a Springfield rifle with a grenade launcher attached. The guy he got it from also had a pack full of rifle grenades, so Pat spent the rest of the Normandy campaign as a grenadier. He described the rest of the Normandy invasion to Gary simply as “one small skirmish after another.” Pat turned from description to philosophy in his journal and wrote:

“Of course there is fear in combat. Some men think too heavily about their chances of getting hit, maimed or killed, and their fear turns into terror, so tortuous that they become unable to function as combat soldiers.

“Others fear personal guilt and public shame from [the possibility of] fleeing during a battle. The mind working too heavily and too often on these thoughts has broken some good men. Once you have disgraced yourself, the agony of this disgrace is never completely bearable.

“Once you get a reputation as a good man in battle, you do your damndest not to tarnish it. Personal honor is valued. Fear of scorn is something you guard against. You have seen others fail and disgrace themselves. You want no part of it, but you realize it could happen to you, so you work at being good at your job and suppressing any thoughts that could hinder your effort.

“You tell yourself you’re young, strong, aggressive, and that getting hit or wounded will happen to others, not to you.”

In his art journal, Pat described the interrogation methods used against captured prisoners, most likely first encountered during the Normandy invasion. Along with the description of interrogation, he included a darkened pencil sketch of two men with a single candle between them. He wrote:

“Many methods were used to gain the necessary information from the prisoners we captured without torturing them. A little theatrical setting [was used] to create tension and terrifying thoughts in the POW. The apprehension, just waiting to be interrogated, not being allowed to relieve their bowels or urinate, was torturous in itself. But these were our orders when we captured a German. Lewis Nixon, one of the original officers of E-Company, was an S-2 in the regiment during combat. If anyone could gain intelligence from a POW, I’m certain [Nixon] ranked with the best.”

On September 17, 1944, Pat jumped with Easy Company into Holland for Operation Market-Garden. He noted that, although the paratroopers drew sporadic enemy fire, the jump was made on a Sunday afternoon in daylight, a “parade ground jump,” easy and straightforward, and nothing like the nighttime Normandy jump.

Still, the jump wasn’t without its fears. Pat had become a squad leader, and replacements had come into the unit. He turned introspective and commented on leadership styles:

“You are committed to make this jump. Your composure in the eyes of the new men will show. Let them see the efficiency of a leader emerge from that force if you’re going to command the respect of your men. Above all, don’t embarrass yourself by showing the least sign of fear, even though it’s there in the pit of your gut.

Easy Company liberated the town of Eindhoven and continued on toward the town of Nuenen. Pat first carried a Thompson submachine gun in Holland, which he didn’t like because of the extensive amount of ammunition one needed to carry along with it.

Of all his war experiences, he wrote most extensively about those near Nuenen:

“Company E boarded the top of the tanks and headed toward Nuenen. E Company’s first platoon was in the lead. First squad of that platoon loaded on the lead tank. I made sure my squad was all aboard, then I boarded. The men left an open spot for me in front right, next to the 75 mm cannon. My pals.

“We moved out toward our objective. When we reached the outskirts of town, a man spotted a German half-track moving across a field on our right flank. He shouted his discovery to the tank commander. Our tank halted. The tank commander traversed his 75 mm and quickly knocked out the German vehicle. The great noise and vibration created by the cannon cleared the tank of men in seconds.

“Because we were so close to entering the building area of the town, we decided to disperse into skirmish lines. There was a house on each side of the street, [each having] a front yard and back yard area, like typical American tract homes. Each property line had a hedge to separate the back yard area from one another. Bull Randleman’s first squad was assigned to the right hand side of the street. The second and third squads to the left side. Bull said he would take the front yard area with the machine gun crew, and I would take the riflemen and sweep through the back yard area toward the heart of town. Tactically, this sounded right. The left side of the street was covered in the same manner by Martin’s and Rader’s squads.

“We moved in unison slowly toward the heart of Nuenen, suspiciously eyeing anything that could hide a Kraut. Suddenly two Germans came out of a second story window. Quickly, they began to move across a roof. In a second, my Thompson was pointed their direction. I pulled the trigger. They were within 35 yards of me, but the gun did not fire.”

There, in the heat of battle, Pat quickly remembered that there was one part in the Thompson easy to get in backwards. The part would fit in two ways, but the weapon would only fire if the part was in the correct position. He had taken the Thompson apart fifty times before he got in the plane, but recounted to Gary later that he obviously had got the part in backward. So Pat field-stripped his submachine gun right there and fixed the problem.

He continued: “This little incident strung the nerves a little tighter. We were moving at a hasty clip—this is what made the two Germans bolt from their concealment rather than fire at us: they knew we would be on them in seconds.”

And then a squad leader’s worst fears were realized.

“The last house had an open field next to it. I parted the foliage of the hedge that separated the field from the house. I must have been spotted by a German machine gunner. Before he could fire, I pushed through the hedge and dropped into a ditch just on the other side. Robert Van Klinken, one of my riflemen, was following me closely. [Van Klinken] peered through the same opening as I had, just as the German machine gunner depressed the trigger. Van Klinken was hit with three bullets.”

Pat later speculated to Gary that the Germans must have zeroed their sights on him in the hedgerow when he went through, then fired at the next man, Van Klinken. Pat grabbed Van Klinken and pulled him through. Van Klinken was still groaning, but dying. The machine gun must have climbed slightly while firing—as they’re prone to do, Pat told Gary—and Van Klinken had been hit in the groin, with two in the chest. The men were still under heavy fire.

“The rest of the riflemen were now in the same ditch as me, looking toward the area that the machine gun fire had come from. Richard Bray shouted to me that he had captured a German at the end of the ditch and wanted to know what he should do with him. I suggested he keep him covered until I could find out what the rest of the platoon was going to do.”

British tanks moved behind Easy Company as they crouched in front of houses. Sergeant Johnny Martin spotted a German tank nearly hidden in a hedgerow, no more than 100 yards away, but the British tanks continued to approach, unaware. The following part of the action is also covered extensively in the HBO miniseries.

Martin ran over to the first approaching tank, stopped the British tank, and quickly explained to the tank commander the location of the enemy tank, just below and to the right of a power pole on his left flank. The panzer was waiting for a shot at the British tank.

The [British] tank commander continued to move forward. Martin again cautioned the tank commander that if he continued his forward movement, the German tank would soon see him.

The British tank commander exclaimed, ‘I caun’t see him, old boy, and if so, I caun’t very well shoot at him.’

Martin shouted, ‘Well, you’ll see him in a minute,” and rapidly moved away from the tank.

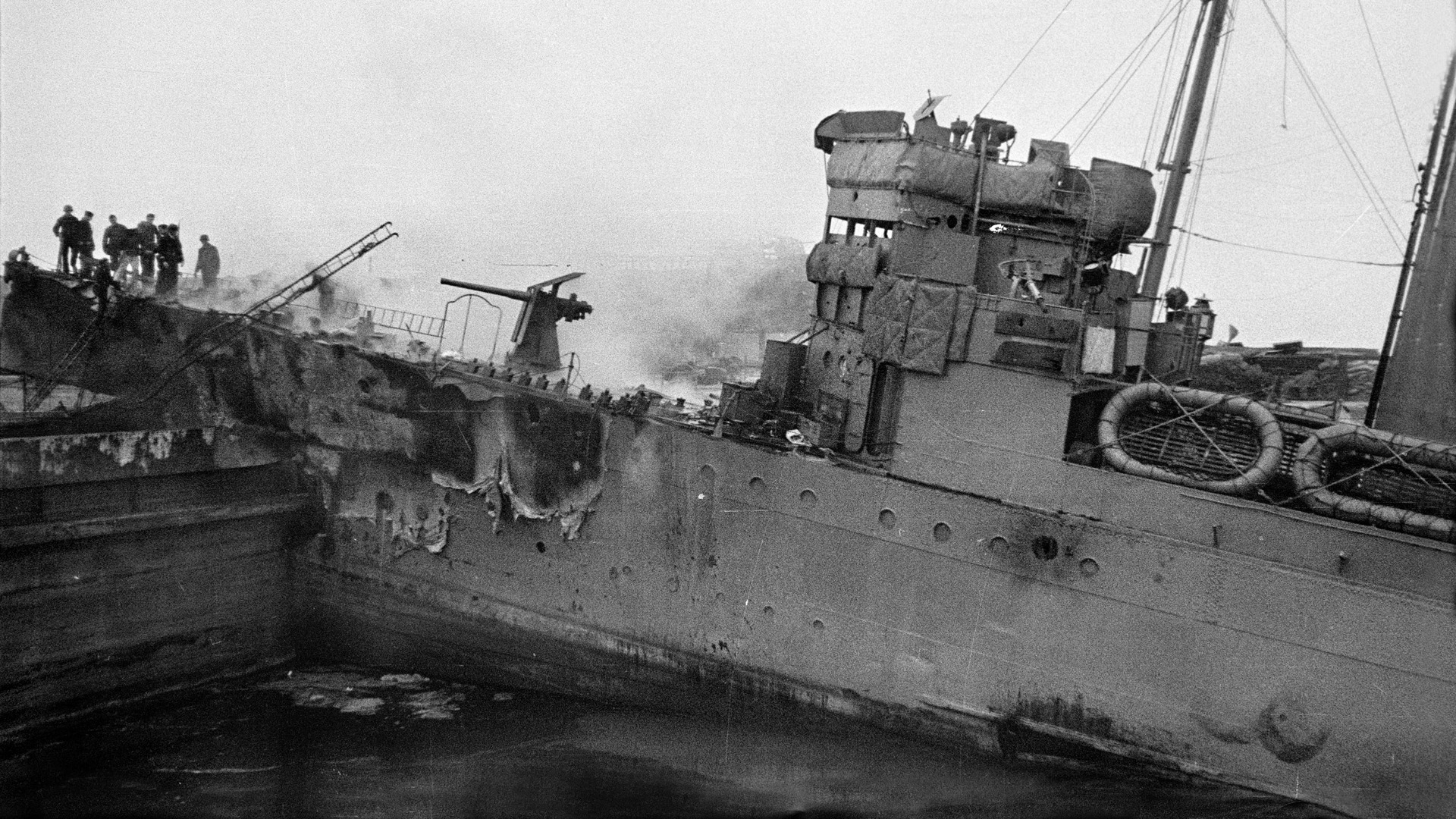

The British tank finally exposed itself to the German tank. [The British commander stood] with his head and shoulders completely exposed in top turret. A sharp Bam! broke the silence. The British tank jumped and shook as the German cannon shot penetrated its armor, taking the legs off the driver. Then came the nauseating interruption of flame that seemed to always follow when a Sherman is hit. “The rest of the tank crew came flying out of hatches I didn’t know existed and ran toward us. The tank continued to move forward at a slow pace. By now it was an inferno. What we did not know was that Bull Randleman was in a ditch next to it, and to keep from being incinerated he was forced to move in the direction of the enemy.

“[Another British tank, following the first British tank] nudged along the same path, as if he had not seen the first tank get hit. The past scene did not influence his caution at all. Bam! Another shot. This time the [second] Sherman shuddered and stopped completely. Again, those who survived came tumbling out of the hatches.

“A German machine gun cut loose to our direct front, biting into the dirt to my left. With so much confusion and bungling, I was oblivious to what was happening to the rest of my platoon. I could not see anyone except four of my men. I cursed the confusion and waited, assuming Lieutenant Peacock would shout out some kind of order. Another burst of machine gun came from the enemy lines. Another shot from the enemy tank hit the house behind us. We had to make a move.

“I shouted to my men to my right, ordering them to get up and move to the rear behind the house. Once behind the cover of the house I shouted to Carl Sawosko to help me carry Van Klinken to the safety of the house. But each time we exposed ourselves, the same machine gun that cut Van Klinken down burned in more bullets.

“[Pvt. Philip] Longo, our first platoon medic, walked over to Van Klinken as if the war had ceased, and picked him up and carried to the cover of the house. [Van Klinken’s] face was ashen; he would soon be dead. The Germans must have seen Longo, but did not fire at him. This had happened before in the case of a medic, if that’s what they thought he was.

“Machine-gun fire was hitting all around the house, and as an organized unit we ceased to exit. Lieutenant Peacock turned his head from side to side, not uttering a word. I said, ‘Lieutenant, if we don’t make a move, the Krauts will soon come in on our flanks.’

“‘Chris, I’m not sure what to do,’ [Peacock said.]

“‘Let’s withdraw—now!’ I said.

“He hesitated. ‘Who’s going to start the withdrawal?’ (The Germans were firing a machine gun in the path of our only escape route.)

“I said to the men around me to move to the rear in two’s and keep spread out. The men began to move. All got clear of the house. Peacock dashed across the danger area and I was close behind him. We ran as fast as we could for several hundred yards when we finally ran into the rest of E Company. We mounted the rest of the British tanks and rode back to Eindhoven.

The rest of the story is also recounted in the Band of Brothers miniseries, told there with slight changes. Pat’s record noted that the next day a British scouting party moved into Nuenen and returned with Bull Randleman. Bull had a bullet hole through his shoulder. Bull told the men what happened to him in the meantime. Pushed into German lines and separated from his men, Bull found an empty barn. A young Dutch girl tried to bandage his wound, then left him alone. He fixed his bayonet to his rifle and waited. Soon a lone German entered the barn. Bull ran him through and hid his body with hay. Bull spent the rest of the night in the barn, waiting for morning. By dawn, the Germans had moved out and Bull was evacuated.

Gary noted how another good buddy of Pat’s, Bill Dukeman, was killed by a rifle grenade a few days later. After the war, Easy Company member Joe Liebgott cut Gary’s hair and sometimes told Gary war stories while he sat in the barber’s chair. Liebgott recounted to Gary that when Dukeman was killed, the men were taking cover in a ditch. The Germans were firing different weapons that burst overhead and dropped shrapnel on the men. One was a rifle grenade that burst and killed Dukeman. A piece of shrapnel went down through his back and through his heart. The deaths of Robert Van Klinken and Bill Dukemen shook up Pat greatly, Gary noted.

Pat later traded his Thompson for an M1 rifle, which he liked much better and used throughout the rest of the Holland campaign. The men fought on the line for seventy days in Holland. On October 3, 1944, Easy Company was relieved from their duty around Eindhoven and transported by truck to an area known as “the Island”––the area between the Waal and the Neder Rhine. The company engaged in various patrols and battles until November when the company was relieved and sent to Mourmelon, France.

In his art journal, Pat depicts and describes several scenes that take place along the dike. One pencil sketch shows a group of men being blown up. Underneath, he wrote:

“Winters passed the order that everyone would open fire when my machine gun commenced firing. As my eyes adjusted to the darkness there seemed to be at least 50 Krauts busy digging in and just milling about the top of the dike. I gave [PFC Dale] Hartley the order to fire, then the whole platoon opened up. Krauts were rolling down the dike toward us like bowling pins and running in all directions. From that very beginning we were hunting, shooting, and capturing Krauts, so the Germans we did not shoot either gave up or ran away. Our casualties were one killed and 15 wounded. The Germans must have lost more than 75 killed, wounded, and captured. That day we were victorious. Tomorrow it may be their turn.”

He also drew a picture of two men in a foxhole in the middle of a storm, looking glumly toward the horizon, and described the weather: “And then there was the rain, the ever-constant rain. The raincoat must have been designed by the Krauts. It kept the rain out, but soon your body would sweat, for the coat could not breathe. You cursed the rain and the coat. You became cold, then even colder, and when you were convinced that your body could stand no more, you found it could.”

On December 18, 1944, Easy Company left their base camp in France and traveled by ten-ton trailer trucks in division convoy to Bastogne, Belgium. E Company was ordered to hold the line at Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge, Hitler’s last desperate bid to turn the tide of war in his direction. They arrived on the morning of the 19th and hiked the rest of the way into the town. Pat describes it as “a dismal, depressing place.”

While marching with the rest of the battalion toward Bastogne, Easy Company was commanded to move from the rear to the point position of the column, the first and most exposed position. Pat turned again to leadership philosophy and recorded his observations of Dick Winters, once his company commander and platoon leader, now a battalion executive, immediately after the command came through. “Captain Winters was standing out in front looking completely, in all respects, as tough as usual, without even trying. I’ve never seen this man show a quarrelsome, pugnacious attitude. When you’re as tough as he is, you don’t have to act tough to prove it. I am sure Winters knew [the gravity] of the situation.”

At Winters’ command, Pat’s squad assumed the scout position. Small-arms fire could be heard in the distance. Soon off the road and into the woods, the density of the woods made forward movement slow. “No opposition,” Pat wrote, “but you’ve experienced enough in this game of war not to allow yourself to become careless or overconfident.”

The unit stopped at the base of a tree line. The men dug foxholes and prepared for the worst. By nightfall, they were completely entrenched. The first flurries of snow came on December 21. The weather grew increasingly cold. That same night a heavy snow fell with “unbearable freezing temperatures.”

Pat picked up the narrative again on December 23, 1944: “The blackness of the early morning surrendered to the new dawn. It was cold and quiet, and snow had fallen intermittently [throughout] the night. The flicker of a small fire could be seen in the rear toward the first platoon CP [command post]. [The fire] was well under control, for there was no tell-tale smoke that a German artillery observer could see. [If there had been smoke,] that area would have been shelled or mortared immediately.

“The early morning hours passed with only the sound of sporadic small arms fire to our left flank and occasional mortar fire a great distance away.”

Pat’s recollections of Bastogne end there, but in his art journal he draws several pictures of his experiences in Belgium. One shows a man’s leg exploding, being hit from mortar fire, the picture a tribute to Bill Guarnere and Joe Toye, who both lost legs in Bastogne. Another shows a jeep being hit by a mortar blast, which Pat saw happen and described. Other drawings depict patrols, tank battles, mortar fire, and hiking toward town on point.

Pat described Bastogne as “the worst artillery he had ever seen,” Gary said. One time they let German tanks go right over their foxholes. Then they stood up and shot the infantry behind the tanks. By the time the tanks turned around, the Americans were gone.

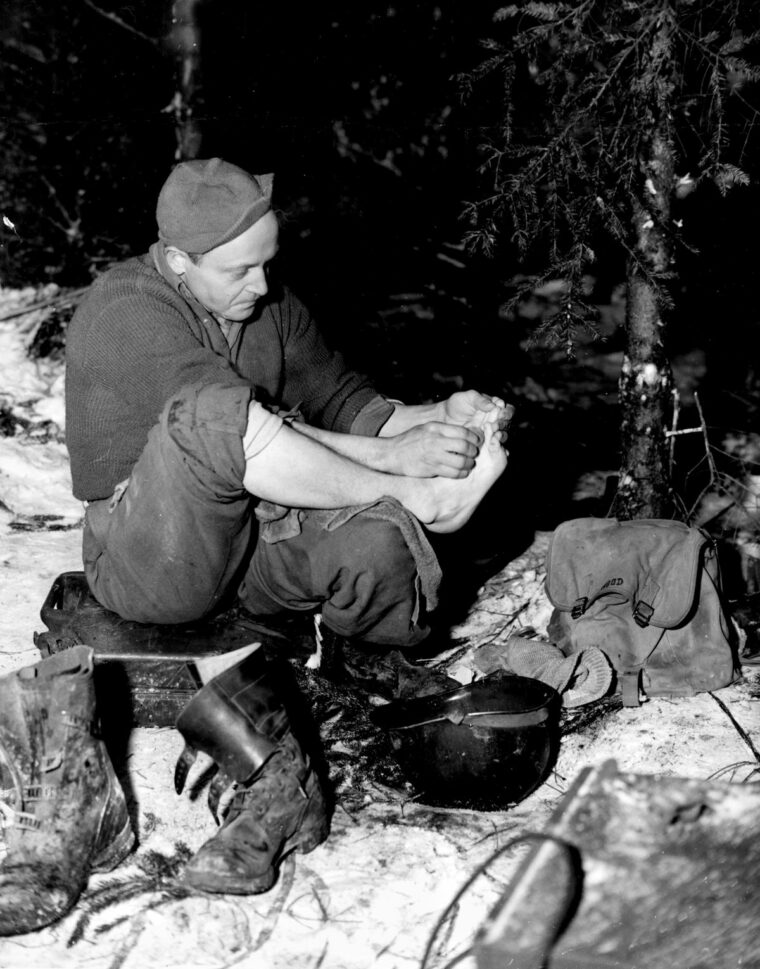

Toward the end of his time in Bastogne, Pat’s feet froze. He was evacuated and hospitalized. Gary said, “I remember when he wrote home about it. The letter said he got to the hospital and the nurse wouldn’t let him take a bath because of his frozen feet, (apparently they didn’t want men recovering from trench feet to be immersed in water). But Pat just couldn’t bear the thought of getting in that clean hospital bed, as filthy as he was. So he took a shower anyway, and the nurse chewed his ass out.”

Pat recounted two other stories to Gary, the first of his wounding. The men were sleep-deprived, walking deadmen almost. Pat was lying in a foxhole with his arm outside the hole. He heard shrapnel coming in but was too exhausted even to move his arm. Sure enough, he was hit in the arm. He didn’t put in for a purple heart. “He figured that after Dukeman and Van Klinken got killed, what he received was nothing,” Gary said.

Later, the men were at an intersection and a German officer came running out of the woods with a “potato-masher” grenade, intent on throwing it. But the grenade went off in the German’s hand, blowing it off. Streaming blood as he was, the German kept his wits and sprinted back into the woods. The men never did get him. They were all still ducking down due to the grenade blast.

Pat continued on with Easy Company until the end of the war. He was with his unit for occupation duties in Germany and Austria.

Then in fall 1945, Gary, now a 10-year-old boy, remembers hearing the good news. “We got a call from my grandmother. ‘Pat’s home,’ she said. I could hear her over the phone. Instantly I was out the door running down the street to their house. My mother yelled at me to come get my jacket, but I wasn’t turning back for anything.”

Pat was a tech sergeant by war’s end. Gary remembers being very impressed with all the stripes and decorations he had, the spit-shined jump boots. “He was a sharp soldier,” Gary said. That first night home, Pat talked about the war, mostly just saying that he was glad it was over. Funny thing was, he looked up at the ceiling inside his parents’ house and said, “Wonder if a mortar could go through this.” Pat wanted to get on with life, same as the rest of the guys. A few evenings later, the family held a big dinner celebration.

Pat went back to his job at the telephone company, but he never seemed to be fully content there. He wanted to be a professional artist or horticulturalist, his other passion. He was also big into physical fitness and, as a side-business, started one of the first public gymnasiums in Oakland, building it in a greenhouse. Famed bodybuilder Jack Lalanne, also an Oakland resident, was a friend and frequented the club. Pat did professional landscaping on the side from 1967 to 1987, building immaculate Japanese gardens.

Pat married his girlfriend, Mary Jo Bonham, in 1947. They had three sons, and bought a big home near Oakland with a huge yard where he created himself a sanctuary with a Japanese garden and wooden decking. He slept outside in summertime.

Chris noted: “My father was probably like many of the fellows who came back. He was haunted by a lot of his war experiences. My room was adjacent to the back yard. I’d have the window open and remember hearing him in the night, many times. He had put stone pathways in the backyard, and I’d hear him walking on the pathways at two or three o’clock in morning. Afraid, I’d go to my mother. ‘Your father’s having funny feelings,’ she said. That was how she put it. It might have been insomnia, or nightmares, but I believe it was post-traumatic stress.

“Later in life I worked as a police officer,” Chris said. “I retired in 2007 after a fairly significant injury, and I grew to recognize what post-traumatic stress looked like. My dad and I grew closer later in life, but he never really did explain what was going on in his head. My mother explained more later on. She said, “Your dad’s reliving the war, having nightmares; he’s thinking about the loss of his buddies, the significant people in his life.”

Mostly, Pat lived for his family. He did whatever he needed to do to care for them. If he took a vacation, it wasn’t for him, it was for the kids, Chris noted. He was an avid bow hunter and fisherman, but never at the family’s expense. He never had an extravagant vehicle. Mostly, he drove older, used cars. He lived a simple life, but he lived it to the fullest.

Pat also spent lots of time creating his artwork, working on his or others’ gardens, sometimes for pay, usually for free. He built a cabin at Lake Tahoe with his sister’s husband. He loved the mountains and ocean. Chris described him as “a universal man. Some of us are good at some things, but Dad was good at many things.”

Pat was a craftsman who built birdhouses and made elaborate wood carvings that were sold in gift shops in San Francisco and Sausalito. He picked up pieces of cedar and pine in the Sierras and carved everything from figurines of American Indians to Jesus.

The family was Catholic, not necessarily devout, Chris said, but they attended church for many years. Pat had an aunt who was a nun. Pat was a highly ethical man and believed in following the Golden Rule. He was always known as a gentleman, even around his war buddies.

Pat started out in the phone company climbing poles with those old straps and spikes. He could shimmy up like a bear. They called his section in the company “craft” because it took an artisan’s and technician’s mind to do it well. He worked his way up to management but hated his new role, so he quit and went back into the field, which floored his wife because it meant a cut in pay, Chris noted.

But Pat was wired as a kinetic person. He had to be able to dig into his work with his hands. He wanted to get out there and get into the wires, not shuffle papers and people. On his 70th birthday, just for fun, he went out and climbed a telephone pole with his old rig. He retired from the phone company in 1977 at age 57.

Pat was big on ethics and doing the right thing. Later in life he told his son that he had always been true to his mother. “They were married a long time,” Chris said, “and I’m sure there were moments they felt less than thrilled with each other. But he never bailed. He never went astray on my mother.”

After Mary Jo got sick in 1997, she passed away very quickly, dying of liver cancer within three months of diagnosis. “It was a shock to everyone,” Chris said, “but it really took my father for a loop. He was absolutely destroyed.” She was just 69 when she died. “After she passed, my dad got good and drunk at the end of her funeral. He said, ‘I’ve lost my wife of fifty years, I just don’t care anymore.’ Dad retreated into grief. It was reflected in his diary and in other papers. Dad lost his passion for life, for his artwork, for writing. He just stopped doing those things.”

Then Pat started to have health problems of his own. First, he had an aneurism, a mini-stroke. “The train just derailed from that point on,” Chris said. The stroke rewired his brain. He was slow and unresponsive, and was placed in a hospital in Salinas, near where his son, Pat Jr., lived.

“Dad was a tough old sonuvabitch,” Chris said. “The hospital called us from time to time, saying things like, ‘Your dad has been very feisty lately.’ A few times he even needed to be restrained because he’d start slugging if he didn’t like what he was getting. He was just confused. For a short time he ended up in an Alzheimer’s facility in Freemont. He didn’t know where he was, or who he was, or what time period he was in. He had lost track of his perception of time, and said things like, ‘Well, [Sergeant Don] Malarkey’s sitting over there. I just told him he had outpost duty.’ I’d say, ‘That’s not Malarkey.’ He’d say emphatically, ‘Of course it is.’ He was just rewired.”

Then, surprisingly, the unthinkable happened. One day Chris visited him in the Alzheimer’s facility and he said, clear as day, “Son, I’ve got to go home.”

“Dad, what are you saying?” Chris said.

“I’ve got to get out of here,” he said. “I’m fine.”

And he was. Pat had defied the odds. His brain had healed. The family had him assessed, and he checked out fine.

The family wasn’t eager to let him be on his own, just yet. Two cousins who grew up with him in Oakland moved into his home with him, staying about ten months. Pat started exercising again. Most of his functioning returned, even to the point where he passed a DMV test and drove a car again. The physician didn’t bark a bit.

Then, he got colon cancer, which they removed, and he was okay.

Then Pat fell in his backyard, broke his arm, and jacked up his hip. “There was only so much the old war bird could take,” Chris said.

Pat’s other son, Tim, had the financial means by then to take care of his father very well. Tim arranged to have a caregiver live with him in his home around the clock. She took good care of Pat, and they had a good friendship.

Toward the end, Pat developed lung cancer. It didn’t come as a surprise. “He had been a chronic cigarette smoker since the war,” Chris said. “That was just the mind-set of that era. They received cigarettes in [the rations] packages back then.”

The doctor said surgery was an option, but that Pat might end up on a ventilator.

“I don’t want to go out like that,” Pat said. “Let the cards fall where they may.”

They didn’t give him a timeline, but toward the end family members knew he was in massive pain. “You could tell by his mannerisms and expressions,” Chris said. “He never complained. He drank wine and self medicated instead.”

He went into a coma with a high fever with short respirations. Then he was gone. He died December 15, 1999, in his own home. His three sons were with him when he passed.

Chris called Bill Guarnere to fill him in. In those days Bill kept track of everybody. Dick Winters wrote the family a letter, which says in part:

“I always took pride in having my best looking man out front carrying the guidon [a small flag carried for marking, signaling or identification] for reviews by dignitaries. And that man, or course, was always Pat, who, with his clean-cut good looks and wide shoulders, proudly carried the Company E guidon.

“When it came time for the big jump in Normandy, I wanted my best, most dependable man right behind me, that man was Pat again.”

The last entry in Pat’s art journal shows a Christmas card he drew in 1944, which he sent to his fellow soldiers in Easy Company. It depicts a helmeted soldier. Underneath is one of his poems:

So you think you’re getting old, Pal, and

time is running short.

Your hair is changing color and thinning,

you report.

You’ve had your good and bad times since

1945.

So best count your blessings, that you are

still alive.

And look upon the bright side,

remember all the young men

we left beneath the ground.

For one day we will see them

where happiness abounds.

You can worry all you’re worth.

When it’s time to bite the bullet, there’s a

better place

than here on Earth.

Merry Christmas,

—Chris

Mighty good.