By David Alan Johnson

“We went to London in ones and twos during our precious 24-hour passes to transfer and pick up our U.S. uniforms,” Pilot Officer James A. Goodson of 133 Eagle Squadron recalled, sometime during the late summer of 1942. By “transfer,” P/O Goodson was talking about the impending Eagle Squadron handover from the Royal Air Force to the U.S. Army Air Forces.

All three Eagle Squadrons knew that it would only be a matter of a few weeks, at best, before they were absorbed into the expanding Eighth Air Force. While the pilots were making their way to London in small groups, someone wrote in longhand across the cover of 71 Squadron’s logbook—71 Squadron was the “senior Eagle” squadron—“Now No. 334 Sq. USAAF.”

Better Food, Better Pay: What RAF Pilots Had to Look Forward to

The first of the Eagle Squadrons, Number 71 had been formed in September 1940, in the midst of the Battle of Britain but over a year before Pearl Harbor. By the middle of 1941, enough Americans had come to England as RAF volunteers to form two more squadrons: 121 Squadron in May and 133 Squadron in August 1941. After flying countless convoy patrols and bomber escort missions and strafing attacks over the enemy-occupied European continent during the past year, the Eagles would be leaving the RAF for the American forces. One of the pilots later said, “We knew that it was only a matter of time until the Eagles would be renamed and most of us would be wearing an American uniform.”

Although some of the Eagles decided to remain in the RAF, the vast majority saw the benefits of joining the American forces and looked forward to the transfer with a great deal of enthusiasm. There were two basic reasons for this enthusiasm: American-style food in the officer’s mess and, especially, American-style pay.

The change in the daily menu was considered a major incentive. There would be no more things like “bubble and squeak” (cabbage and potatoes) to endure. Instead, the pilots would have steaks, chicken, real fruit and vegetables, American coffee, and other things they had not seen since they left home. The British Isles had a good many admirable things about them, but the British wartime diet was not among them.

The biggest and most impressive change of all was in the rate of pay between the RAF and the U.S. forces. The U.S. government paid its personnel between two and three times the amount earned by their RAF counterparts. A pilot officer in the RAF was paid roughly $67.00 per month (actually, 16 pounds, 14 shillings, and 7 pence). A second lieutenant in the USAAF, the equivalent of a pilot officer, received $162 per month.

During 121 Squadron’s farewell party, a departing Eagle pilot informed an RAF Wing Commander, “We can’t afford not to go. Do you realize, Wingco, as of now, I’m being paid about twice as much as you if not more—and I’m only a lootenant. Too bad you don’t qualify to come with us, your accent would be worth every cent of your pay—what, what, old boy?” The U.S. equivalent rank of wing commander is lieutenant colonel.

What Eagle Squadron Pilots Had to Do to Transfer to the Eighth Air Force

Before they could transfer into the U.S. forces, every pilot had to travel to London for an examination by a board of American officers. Among those on the board were two of the Eighth Air Force’s highest ranking officers: Maj. Gen. Carl A. Spaatz, commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces in Britain, and Brig. Gen. Frank O. Hunter, head of U.S. Fighter Command.

After being questioned by the board, the pilots were sworn into the U.S forces. Most entered the Eighth Air Force with the rank that corresponded with their current RAF rank: flight lieutenants became captains; squadron leaders became majors. Sergeant pilots were commissioned into the USAAF as second lieutenants.

Some pilots had their own ideas of what their new rank should be. Squadron Leader Carroll McColpin informed the examining board that he ought to be promoted to brigadier general. The American forces would be getting a seasoned and experienced combat leader, he argued, and paying him a brigadier’s salary would represent a sound investment. He allowed himself to be persuaded into settling for the rank of major.

Squadron Leader William Dunn, who was officially credited with being the first American ace of World War II, had an altogether different reaction toward making the transfer. Over a year before, in August 1941, Dunn had been badly injured in combat while he was still a member of 71 Squadron. By the autumn of 1942, he had recovered from his injuries and was serving as acting squadron leader of 130 Squadron, which was stationed in Canada. Dunn was well aware that most American pilots in the Royal Air Force were exchanging their RAF blue uniforms for U.S. khakis, but he did not have much interest in leaving the British forces.

A letter from an organization called The United States Inter-Allied Personnel Board gave Squadron Leader Dunn second thoughts. The letter was not at all friendly. “It was sort of implied that if I didn’t agree to a transfer, they’d come and get me,” Dunn recalled. Although S/L Dunn was not intimidated by the nasty letter, he was persuaded by the generous U.S. pay and allowances. He agreed to the transfer and was released from the RAF in June 1943.

There was actually no law that could compel William Dunn, or any other American, to transfer to the U.S. forces. Anyone could remain in the RAF if they decided to do so. James C. Nelson of 133 Squadron is one Yank who elected to remain in the RAF and spent the remainder of the war in the British forces. When the war ended, he returned to the United States.

No one can say for certain exactly how many Yanks stayed in the RAF, since nobody knows how many Americans served with the British forces in the first place. Joining the armed forces of a “belligerent nation,” including Britain, was a violation of the U.S. Neutrality Acts in 1939 and 1940. Anyone caught trying was subject to a $20,000 fine, 10 years in prison, and loss of U.S citizenship. Some of the volunteers came to Britain by way of forged passports or other illegal documents. It was best for them to keep their mouths shut about their true nationality, and staying in the RAF was the safest bet for such individuals. They were afraid of going to jail if the U.S. or the British authorities ever discovered what they had done.

“Half In, Half Out” of U.S. Forces

Throughout the summer, all three Eagle Squadrons continued to escort bombing missions over France as well as to fly convoy patrols. The Luftwaffe rarely came up to challenge these flights. A frequent entry in squadron logbooks is “no enemy aircraft seen.”

Once in a while, though, the enemy did decide to come up. Whenever that happened, the result was a short, violent combat. On August 21, 71 Squadron was flying another routine escort mission when the Luftwaffe made an appearance. During the next few minutes, 71’s pilots claimed two enemy aircraft destroyed along with one probable and also lost one of their own Spitfires to enemy fighters.

The Eagles kept up a strange existence throughout August and September, half in and half out of the U.S. forces. Many of the pilots had already been commissioned as officers in the USAAF by this time, but they were still on “detached service” with RAF Fighter Command. They still flew Spitfires marked with the RAF roundel insignia and still wore their RAF blue uniforms. Some had not even bought their U.S. uniforms. Even though they were finally members of the American air force, they were still in the British forces.

Everyone was well aware that their leaving the RAF would be only a matter of a couple of weeks, though. On September 5, Pilot Officer Dan Young of 121 Squadron spotted a Junkers Ju-88 bomber near Southend-on-Sea that was being attacked by Spitfires from another squadron. P/O Young chased after the Junkers, which was already burning, and gave it two bursts of cannon fire. The German bomber crashed into the River Thames estuary “with a huge splash,” according to the squadron’s logbook. This would be the last enemy claim that 121 Squadron would make. A few shots would be fired at Focke Wulf FW-190 fighters during regular fighter sweeps, but no further claims would be made.

Unfriendly Rivalry: How the Mark IX Drove Another Wedge Among the Three Squadrons

Even though preparations were already underway to absorb the Eagle Squadrons into the U.S. forces, there was one problem that would not go away: The three squadrons had developed an unfriendly rivalry among themselves. The Eagles did not like one another and made no bones about it.

The pilots of 71 Squadron considered themselves to be the best of the all-American fighter units and made no secret of their opinion. Number 121 Squadron did not like hearing about the accomplishments of the “Senior Eagles” and resented being referred to as the “Second Eagles,” as though they were somehow second-class citizens. And 133 Squadron had to put up with being called “junior” by the other two units. The situation was not a happy one.

The rivalry did not diminish with time as RAF Fighter Command had hoped. If anything, it had grown “to the point where it was causing concern to various wing commanders,” as one historian said. Even though all the pilots were American, the only thing they seemed to have in common was hostility. Keeping the three squadrons based at separate airfields seemed to be the only solution to that particular problem.

The problem was not going to trouble the RAF for much longer, though; the Eighth Air Force was about to inherit the situation. After the Eagles had been absorbed into the American forces, the plan was to base all three squadrons at one station and incorporate them into one group: the U.S. Fourth Fighter Group. But if the three units kept on with their feuding and squabbling, any such arrangement would be impossible. They would spend more time fighting with each other than with the Germans.

This attitude problem developed a new wrinkle in the middle of August 1942, when 133 Squadron was issued the new Spitfire Mark IX. The Mark IX was the latest version of the Spitfire, developed to compete with the FW-190. It was faster, had a better rate of climb, and was more heavily armed than the Mark V, which it was supposed to replace.

The new Mark IX was certainly a status symbol. Only three squadrons throughout the RAF had them—133 and the other two squadrons stationed at Biggin Hill, in Kent—and every fighter unit in the RAF wanted them. Because it had been issued the Mark IX, 133 Squadron claimed this as a “sign of superiority” over both 71 and 121 Squadrons. The other two squadrons resented this attitude.

“We had the best planes,” one of 133’s pilots said. “We had dawn readiness—71 didn’t. We would scramble in the darkness. We considered ourselves the best without question. One-three-three was number one among the Eagles.” The pilots of 71 Squadron emphatically did not agree. As far as they were concerned, they were the best of the Eagles. And 121 did not want to hear that the other two Eagle Squadrons thought they were the best.

This sounds juvenile and petty, but the resentment among the three squadrons was deep and bitter. There could be no possibility of basing them at the same airfield as long as feelings were running so high. By September 1942, the problem had become a pressing concern for the Eighth Air Force. The Eagle Squadrons were scheduled to be transferred to the U.S. Army Air Forces later that month.

121 and 133 Finally Join 71 Squadron in Essex

But senior officers decided to go ahead with their plan just the same. On September 23, both 121 and 133 Squadrons joined 71 Squadron at its base in Debden in Essex. This was the first time all three had been based at the same station. The officers wanted to see if their experiment would work and hoped for the best.

“The nearby village of Saffron Walden would not be losing its boisterous Yanks,” according to 71 Squadron’s logbook. With all three squadrons now at RAF Debden, there would be three times as many Yanks as before, for better or worse. Saffron Walden was the nearest village, about three miles away from Debden, and was also the closest spot for rest and relaxation for the pilots and their crews.

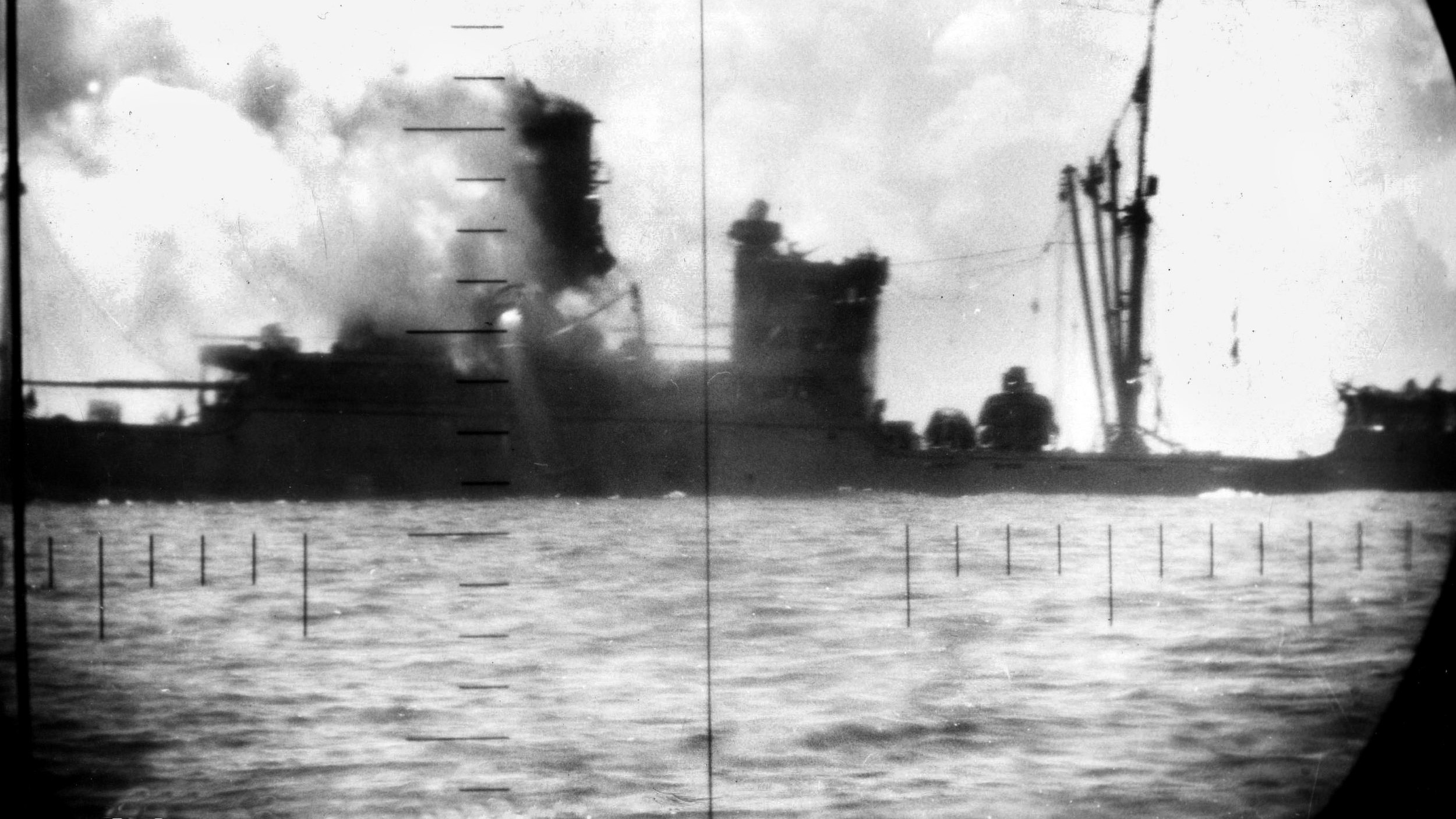

Why the Morlaix Mission Was Plagued with Problems

Three days after arriving at Debden, 133 Squadron was sent off to the RAF airfield at Bolt Head, near the city of Exeter, to prepare for another bomber escort mission. From Bolt Head, the 12 pilots would fly fighter cover for the U.S. 97th Bomb Group, a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress unit. The 97th would be flying a bombing raid against the city of Morlaix, in Brittany, which was the site of a Focke-Wulf maintenance plant as well as a major rail center for the area.

The pilots thought that Morlaix would be just another routine escort job—take the bombers to their target and escort them back again. Hardly any of the pilots bothered to attend the preflight briefing. They had done the same sort of assignment many times before and knew the coast of Brittany almost as well as they knew the south coast of England—“like the backs of our hands,” according to one pilot.

Unfortunately, the “routine” operation went wrong from the beginning. According to plan 133 Squadron was to rendezvous with the 97th Bomb Group over the English Channel, at a point about halfway between Bolt Head and Morlaix, along with the Spitfires of both 401 and 412 Squadrons. But the Fortresses arrived at their rendezvous point about 20 minutes early and continued on to their target without waiting for their escort.

While the Flying Fortresses went on toward Morlaix, the Spitfires kept circling the Bay of Biscay, waiting for orders and burning up fuel. After circling the bay several times, ground control in England finally ordered the fighters to fly after the bombers, catch up with them, and escort them to Morlaix.

The mission should have been aborted—it was normal procedure to cancel an operation if the rendezvous point was missed by as little as half a minute. But this was not a normal operation; it was being carried out for the press and publicity units, to give them both a good story. The most widely reported rumor was that ground control sent the Spitfires after the Fortresses because of pressure from senior officers in the Eighth Air Force.

But there was another problem as well. Besides being kept orbiting the Bay of Biscay, the pilots were also given an incorrect wind speed estimate when they were sent off to find the American bombers.

The Spitfire pilots had been informed that they would be flying into a 35-knot headwind, which would slow their forward speed. But the Spitfires were actually flying into the jet stream, a high-speed wind current that was just about unknown in 1942. Instead of a 35-knot headwind, the jet stream gave the fighters a 100-knot tailwind at 28,000 feet. All this added up to a 135-knot miscalculation.

It should have taken the fighter escort 33 minutes to reach their destination, taking the 35-knot headwind into consideration. But because of the jet stream and the 135-knot error, the Spitfires actually flew more than 100 miles beyond their projected destination during their 33-minute flight. Because of the 8/10 overcast that covered most of northern France that day, none of the pilots could see anything underneath their fighters except a solid layer of gray cloud. Blown many miles to the south and unable to identify anything on the ground, the pilots had no real idea of where they were.

Ground control in England could track the Spitfires on radar but could not give the pilots their position—the Luftwaffe was listening. Eventually, the three Spitfire squadrons did run into the Flying Fortresses they were supposed to be escorting. The bomber pilots had given up trying to find Morlaix through the cloud cover and turned back for England. The fighters joined up with the bombers, hoping that they would lead them home.

Because they had burned up so much fuel over the Bay of Biscay, the pilots began dropping through the cloud layer after only about half an hour with the Fortresses. They were completely disoriented and thought they must be over southern England by that time. They hoped they might be able to spot some nearby airfield where they could land and refuel.

But they were not over southern England. They were still over Brittany. As soon as they dropped below the clouds, the Spitfires came under almost immediate attack, first by antiaircraft fire, then by FW-190s.

The pilots could not do very much about taking evasive action; they did not have enough fuel left. Each pilot called out his position and his situation and then did whatever he could to save himself. Some bailed out. Others crash landed. One pilot was shot down and killed over Brittany. Only one pilot managed to fly back to England. Richard N. Beaty crash landed his Spitfire a few miles inland from the coast, out of fuel.

Of the 36 Spitfires—three full fighter squadrons—that took part in the Morlaix operation, 22 were lost. Of the three squadrons, 133 fared the worst. Four of its 12 pilots were killed; six either bailed out or crash landed in German-occupied France and were taken prisoner. All 12 Spitfires were lost.

Number 133 (Eagle) Squadron no longer existed, except on paper at the Air Ministry in London. Replacement pilots were quickly sent to Debden along with replacement aircraft. There were no more Spitfire Mark IXs available, so 133 Squadron was reequipped with the older Mark V.

Pilot Officer James Goodson happened to report for duty on the same day as the Morlaix raid. The only other pilot he met at the nearly deserted fighter base was P/O Don Gentile, who did not go to Morlaix with the rest of the squadron. Gentile told Goodson and another new arrival, “I sure am glad to see you. I’m all alone here.”

133 Squadron Gets Wiped Out (and Goebbels Capitalizes on the Morlaix Disaster)

Dr. Josef Goebbels’ Propaganda Ministry in Berlin immediately broadcast the news of the disaster. Twenty-two RAF Spitfires had been brought down by the Luftwaffe, the broadcast said, and several Americans were among the pilots who had been taken prisoner. As soon as reporters in Britain heard the news, they started asking questions about what happened. The Air Ministry and the Eighth Air Force informed the press that the fighters had been lost due to adverse weather conditions and wing icing. Reporters duly wrote that all 22 Spitfires crashed because of heavy icing on the wings; it was the only information they had.

Morlaix was a disaster for 133 Squadron, but one good thing did come out of it; it played a large part in doing away with the unfriendly rivalry between the three Eagle Squadrons. Number 133—“junior,” “third Eagles”—had been wiped out. The catastrophe ended all the animosity and name-calling. Bad feeling was instantly replaced by sympathy, and the conflict and all the cutting remarks of the past year were forgotten. Both 71 and 121 Squadrons knew all too well that what had happened to 133 could just as easily have happened to them.

The Eighth Air Force planners took their own steps toward ending the rivalry. All three of the former RAF squadrons were mixed together; not one of the original Eagle Squadrons was left intact. Each individual squadron of the new Fourth Fighter Group incorporated members from all three squadrons; 71 Squadron was now the 334th Squadron, 121 was the 335th Squadron, and 133 had become the 336th Squadron. But all the sympathy offered to 133 Squadron in the wake of the Morlaix raid helped to unite the three units more effectively than any plan the Eighth Air Force might have thought up.

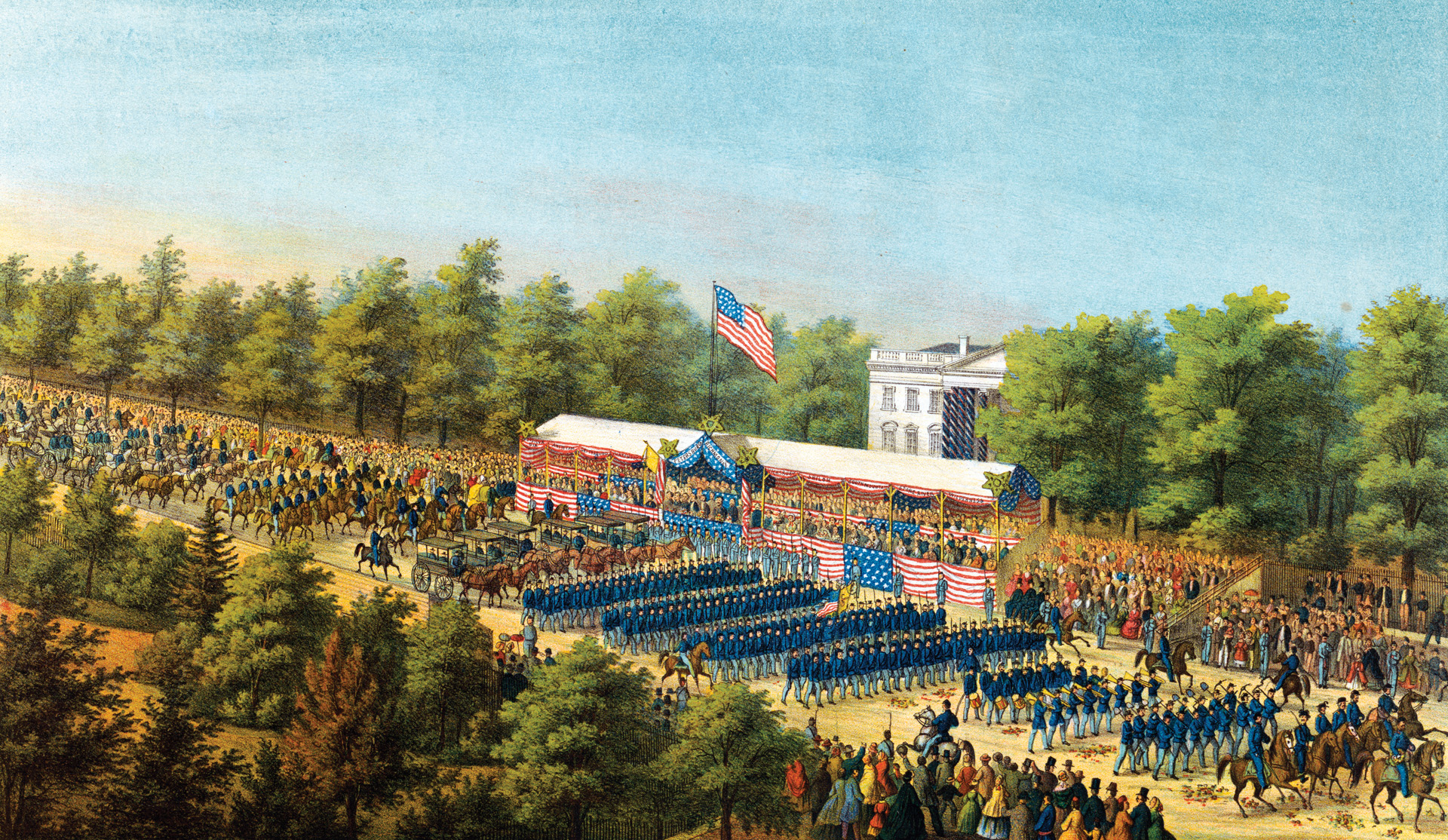

The three Eagle Squadrons officially left the Royal Air Force on September 29, 1942, in a formal ceremony filled with speeches and fanfare. Among the officers present were Maj. Gen. Carl Spaatz, commander of the Eighth Air Force, and Sir Sholto Douglas, chief of RAF Fighter Command.

Sir Sholto Douglas wished the departing Eagles a fond farewell and expressed regret that the Americans were leaving the RAF—gracious words that he could now afford to make. Since 1941, when 71 Squadron was first formed, Douglas had often been furious with the Eagle Squadrons concerning their conduct. In the early part of 1941, he told American General Henry “Hap” Arnold that 71 Squadron’s performance was “unsatisfactory” and that there was the possibility of disbanding the squadron and sending all the pilots back to the States.

Besides making the usual polite remarks, the sort of comments that are always made on such occasions—“We at Fighter Command deeply regret this parting”—Sir Sholto also gave a brief history of the Eagles, including their total number of enemy aircraft destroyed. “Eagle pilots have destroyed some 73 enemy aircraft, the equivalent of about six squadrons of the Luftwaffe.” A moment later, he amended the score to 73½. The half was a Dornier Do-17 bomber that was shared with a British pilot from another squadron—“a symbol of Anglo-American co-operation,” Sir Sholto called it.

For the first few weeks, at least, the pilots of the new Fourth Fighter Group felt foreign and out of place in the U.S. forces. It would take a while to accustom themselves to American ranks and to saying “lieutenant” instead of “leftenant.”

The Eagles Keep Their Spitfires

At least the Eagles would not have to adjust to new fighters. When they transferred to the Eighth Air Force, they would be taking their beloved Spitfires with them. This made the former Eagles a happy group of pilots. As far as they were concerned, there was no American fighter that could hope to compete with the Spitfire, not to mention the Messerschmitt Me-109 or the FW-190. The Fourth Fighter Group would be equipped with Spitfire Mark Vs, courtesy of the Royal Air Force. The British referred to this as “reverse Lend-Lease.” Only the national insignia would be changed; the white U.S. star inside a blue disc would be painted over the red, white, and blue RAF roundel.

The fact that American pilots preferred the Spitfire to an American fighter produced no small amount of embarrassment back in the United States. An American pilot was quoted in New York’s Herald Tribuneas declaring that he was “glad they had Spitfires instead of P-40s and Airacobras.” The story was repeated in Timemagazine, where it received national circulation and also caused faces to turn red from coast to coast. No one in the War Department wanted to hear that any foreign airplane was better than anything made in the USA, even if it happened to be true.

The Fourth was reequipped with the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt in the early part of 1943 and would be reequipped again with the North American P-51 Mustang in February 1944. The former Eagles were the first to convert to the Mustang, which is generally regarded as one of the outstanding fighters of the war. With the P-51, the Fourth dramatically increased its total of enemy aircraft destroyed. During March and April 1944, the group destroyed 189 German aircraft in the air and another 134 on the ground. This earned the Fourth a Presidential Unit Citation, the highest award that any American unit could receive.

By the end of the war, the Fourth Fighter Group’s final score was 583½ enemy aircraft destroyed in the air and another 469 on the ground, for a total of 1,052½. This made the Fourth the top-scoring American unit in the European Theater of Operations. Hubert Zemke’s 56th Fighter Group, the Fourth’s main challenger for the highest number of confirmed enemy victories, destroyed fewer enemy planes—985. But its members are quick to point out that the 56th destroyed more planes in the air, in actual combat—a total of 674½—than the Fourth.

At the “handing over” ceremony in September 1942, Sir Sholto Douglas ended his presentation with, “Good-bye and thank you, Eagle Squadrons of the Royal Air Force. And good hunting to you, Eagle Squadrons of the United States Air Force.”

The Lasting Legacy of the Eagle Squadrons

In 1940, when 71 Squadron was being formed, the American volunteers who had come to England and joined the RAF had actually violated the U.S. Neutrality Acts. Every one of them had broken the law; some had lost their American citizenship. Just a little over two years later, and eight months after Pearl Harbor, all of this was conveniently overlooked. The Eagles, along with their “operational experience,” were officially welcomed into the U.S. Army Air Forces by one of its commanding generals. James Goodson pointed out, “When the U.S. entered the war, they desperately needed experienced Air Crew, so they did everything they could to facilitate our transfer, including restoring U.S. citizenship if it had been lost.”

Forty-four years after the Eagles transferred to the American forces, a permanent memorial was dedicated to all those who flew with the all-American squadrons—a granite obelisk inscribed with the names of the pilots of 71, 121, and 133 Squadrons and topped by an American eagle. Appropriately, the memorial is installed in Grosvenor Square, London’s most American place, which has been the site of the U.S. Embassy ever since the 13 original colonies won their independence from Great Britain.

After all the speeches had been given and all the fanfares had been played, the Stars and Stripes was raised alongside the RAF’s blue battle duster and the band played “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The transfer ceremony was finally over; the pilots were dismissed. “The Squadron then marched from the parade ground as No. 335 (USA) Squadron, under the command of Major W.J. Daley, DFC. (Formerly Flight Lieutenant Daley.)” This was the last entry in 121 Squadron’s logbook. The other two squadrons marched off the field along with Major Daley and his pilots.

“Swinging their arms straight from the shoulders with their heads held high,” wrote the biographer of 71 Squadron, “the Eagles passed smartly in review, and passed out of the Royal Air Force.” A British writer summed up the transfer ceremony in a different way: thus ended the “riotous, semi-independent career” of the American Eagle Squadrons.

David A. Johnson has written for WWII History on a variety of topics. He is also the author of numerous books on subjects ranging from the Civil War to World War II. He resides in Union, New Jersey.