By Chuck Lyons

On August 3, 1864, near Atlanta, Georgia, Captain Henry Lawton of Indiana led a group of Union skirmishers in a charge against Confederate rifle pits. Lawton and his men took the pits and held them, successfully beating beat back two enemy counterattacks. For his actions that day, Lawton was awarded the Medal of Honor. But what for many would have been the pinnacle of a military career was only the beginning for Lawton. He was to continue in the army for the next 35 years and rise to the rank of major general.

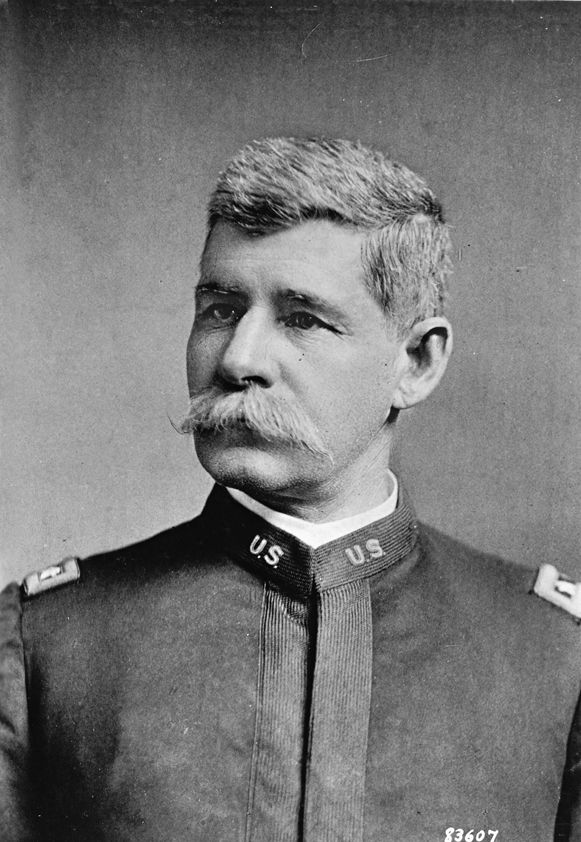

Military in bearing, tall (he was six-four), with a flowing mustache, Lawton had the distinguished look of a military leader. He embodied the heart of a warrior as well, refusing to take shelter when under fire and always staying at the front with his men, who consequently adored him. Lawton modeled himself after the great British war leaders of the past, going so far as adopting the British pith helmet for his personal use. He quickly became a darling of the American press and a legend to the American public. And he won battles, which helped his popularity immensely.

An Indiana Volunteer

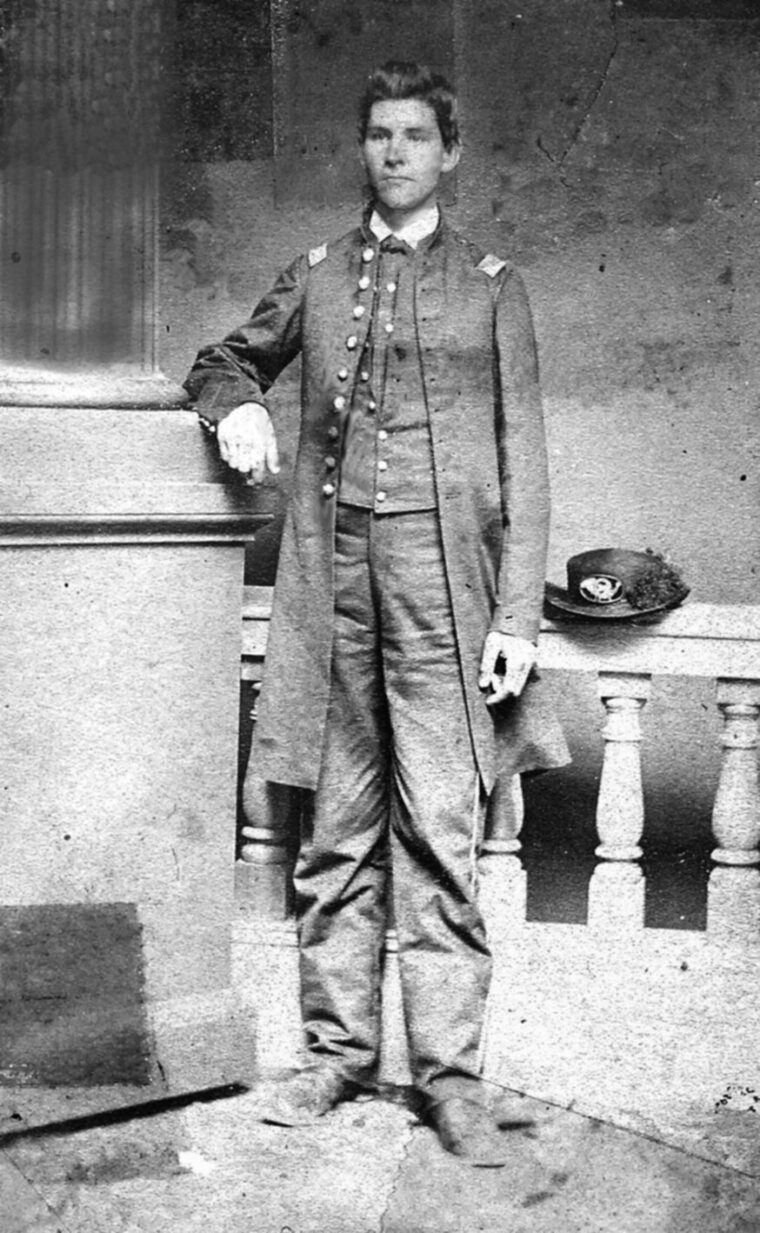

Lawton was born March 17, 1843, in Maumee, Ohio, but moved with his family to Fort Wayne, Indiana, where he grew up. He was studying at the Methodist Episcopal College there when the Civil War began and was one of the first men there to answer Pesident Abraham Lincoln’s call for three-month volunteers, signing on as a private with the 9th Indiana Volunteers. He mustered out on July 21, 1861, and returned home to Indiana before re-enlisting in the 30th Indiana Volunteers in August. He was promoted to first lieutenant that same month and to captain in May 1862. By the end of the war, Lawton had reached the rank of brevet colonel, a promotion he received for distinguished service in the field. During the war he saw action in some 22 engagements, including Shiloh, Corinth, Stones River, and Chickamauga, as well as in the Atlanta campaign, where he was awarded his Medal of Honor.

“A Remarkable Pursuit” of Geronimo

After the war, Lawton left the army to study law at Harvard but, urged on by General Philip Sheridan, he accepted a second lieutenant’s commission in July 1866 and traveled west to serve under the famed Indian fighter Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie. He saw action with the 41st and 24th Infantry Regiments and eventually with the 4th Cavalry and was commended for his “vigilance and zeal, rapidity and persistence of pursuit” and “for [his] great skill, perseverance, and gallantry.” Lawton was involved with Mackenzie in 1874 in the fight at Palo Duro Canyon in the Texas Panhandle.

In March 1879, Lawton was promoted to captain, and in 1886 he was named to command Troop B of the 4th Cavalry out of Ft. Huachuca, Arizona. There, he was selected to lead an expedition into Mexico against the feared Apache warrior Geronimo and some 50 of his followers who had escaped from the White Mountain reservation. Lawton and his men chased the Indians for some 2,000 miles. During the chase he employed a recent British invention, the heliograph, to keep in touch with his scouts and patrols. The heliograph, which had been developed by the British Signal Corps in India, used reflected sunlight to send messages in Morse code. Since it weighed only seven pounds, it was ideally suited for desert use.

Lawton’s expedition finally tracked down Geronimo in Mexico, where he and his remaining 17 followers surrendered to a small party led by Lieutenant Charles Gatewood. Lawton led the captives back north to Skeleton Canyon in southern Arizona, where the Apaches officially surrendered to General Nelson Miles on September 4. The Indians were moved 60 miles north to Fort Bowie and then shuttled to several different locations before finally being setted in Oklahoma, ironically near the site of what would eventually become Lawton, Oklahoma.

The Apache leader himself credited his capture to Lawton’s tenacious pursuit, which gave the Apaches little chance to rest or remain in one place for long. Miles called Lawton’s expedition “a remarkable pursuit,” noting that it had crossed 10,000-foot-high mountains and traveled through canyons “where the heat in July and August was of tropical intensity.”

Fighting the Spanish American War in Cuba

On September 17, 1888, Lawton was promoted to major and made inspector general of the army in Arizona. The following year he was promoted to lieutenant colonel, and in May 1898 he was named a brigadier general and assumed command of the 2nd Infantry Division, V Corps, which was being sent to Cuba, where the Spanish-American War had recently broken out.

It was in Cuba, and later in the Philippines, that Lawton was to reach his greatest glory. His 6,000-man 2nd Division spearheaded the invasion of Cuba at Daiquiri, a shallow beach 18 miles east of Santiago, on June 22, 1898. He was also called on to successsfully assist Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, who had met stiffer than expected resistance at Las Guasimas.

After the landing, Lawton began leading his men west toward Santiago, meeting only scattered resistance. As the force approached the city, Lawton was delegated to take El Caney, six miles northeast of Santiago and guarding the city’s flank. El Caney, it was believed, should be taken in two or three hours, after which Lawton was to march his men along the main road and take a position on the right flank of the force assembling to attack San Juan Hill.

The attack on El Caney was slated for daybreak July 1, with Lawton’s men supported by only one light artillery battery. At 6:30 am, the artillery opened up on the dug-in Spanish positions at El Chaney including its strongpoint, the fort of El Viso. The infantry began firing at 7 am, but it soon became clear that the position would not fall in the proposed two or three hours. In fact, the 521 Spanish defenders were to hold out for a full eight hours.

At noon, Maj. Gen. William Shafter, who was in overall command, ordered Lawton to drop the El Caney attack, fearing the American forces were becoming too spread out. Lawton replied that withdrawal would be tantamount to defeat and that his forces were too deeply engaged to withdraw. Shafter conceded, and the attack continued.

Shortly afterward, Lawton’s artillery, which had been firing with little effect all morning, finally got the range of the fort, and at about 3 pm the 12th infantry overwhelmed El Viso. Some 235 of the defenders were killed or wounded and another 120 made prisoner. On the American side, Lawton suffered heavy casualties, seeing 81 of his men killed and another 360 wounded. Following the battle, Lawton moved to the right of the American line at San Juan Hill, with orders to link up with the rest of the forces on July 2. They subsequently took part in the famous attack on San Juan Hill and the ensuing siege of Santiago.The city capitulated on July 4.

“America’s Lord Kitchener”: Lawton in the Philippines

Lawton was named one of Shafter’s negotiators at the surrender talks and was present at the formal Spanish surrender on July 17. He was appointed military governor of Santiago province before being reassigned for health reasons to command IV Corps in Huntsville, Alabama. At the time, it was believed by some that Lawton’s alleged heavy drinking was the actual reason for his reassignment. Rumors of excessive drinking had haunted him throughout his career and would continue to haunt him throughout the Philippines campaign.

Back in the States, Lawton attracted the attention of President William McKinley, who had heard of Lawton’s exploits, and he offered the stateside general command of field forces in the Philippines. At the time there was no fighting in the islands. A nasty conflict was to break out shortly thereafter, however, between the United States and Philippine insurgents who objected to the United States takeover of the islands. Maj. Gen. Elwell Otis was given overall command of the Philippine operations. Lawton sailed in January 1899, believing he would be in charge of field forces in the islands as McKinley had indicated, while Otis would handle mainly administrative affairs.

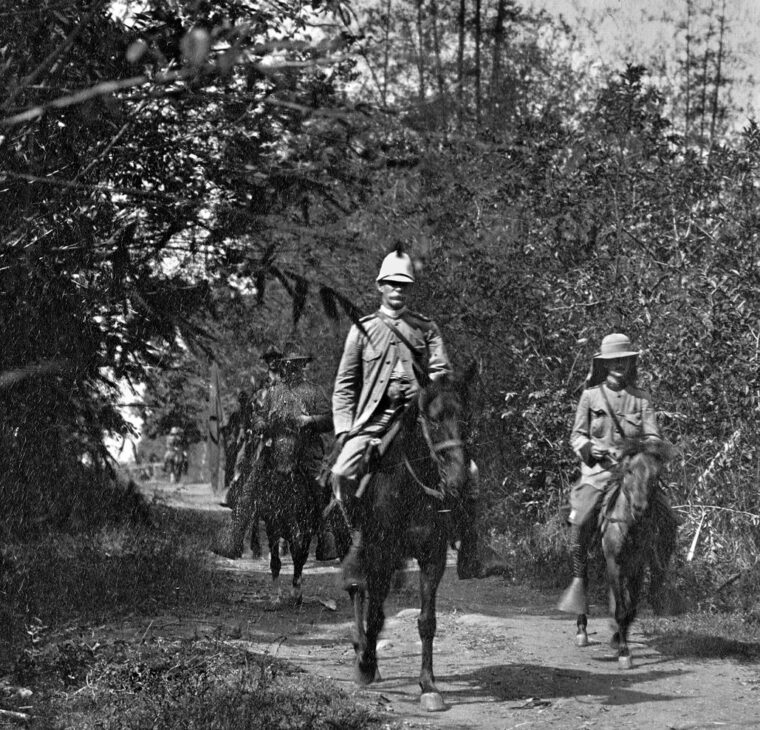

The arrangement, or at least Lawton’s understanding of it, led to numerous conflicts between the two generals. By this time, Lawton had built his reputation to almost legendary status with the American public. He was immensely popular with his troops and also with the press, which he assiduously cultivated. He consciously modeled himself on a British colonial officer, wearing a pith helmet, sporting a well-groomed look, and riding erect on a coal-black horse or striding distainfully along the front line of an engagement. One observer called him “America’s Lord Kitchener,” referring to the popular and successful British soldier of roughly the same period. With his flowing mustache, great height, and imposing presence, Lawton provided a stark contrast to the far less vital looking Otis, who was considered timid and secretive by his troops and indeed may have been the only officer in the Philippines who never saw any actual fighting.

Hostilities had broken out in the islands on February 4, 1899, when Private William Grayson of the Nebraska Volunteers fired at a group of Filipinos approaching his position, provoking an armed response that quickly escalated into a full-scale war as shooting spread up and down the 10-mile-long U.S.-Filipino lines, causing hundreds of casualties. By the end of the conflict in 1902, a total of 4,234 American troops had been killed and 2,818 wounded, against an estimated 20,000 Filipino combat deaths and possibly as many as 200,000 civilian deaths, mostly from disease and privation connected with the fighting.

Lawton, who arrived in March, immediately responded to the fighting, employing counterinsurgency tactics to combat the Filipino fighters, tactics based in large part on what he had learned fighting Indians in the American West. He quickly won victories at San Isidro, Santa Cruz, and San Rafael, continuing his style of “leading from the front,” a technique that had worked well for him in the Civil War and the West.

Otis relegated Lawton mainly to diversionary attacks and smaller operations while giving the major operations to General Arthur McArthur, whose son Douglas would direct Philippine operations in World War II. Undaunted, Lawton was able to turn those minor operations into victories.

The Death of General Henry Lawton

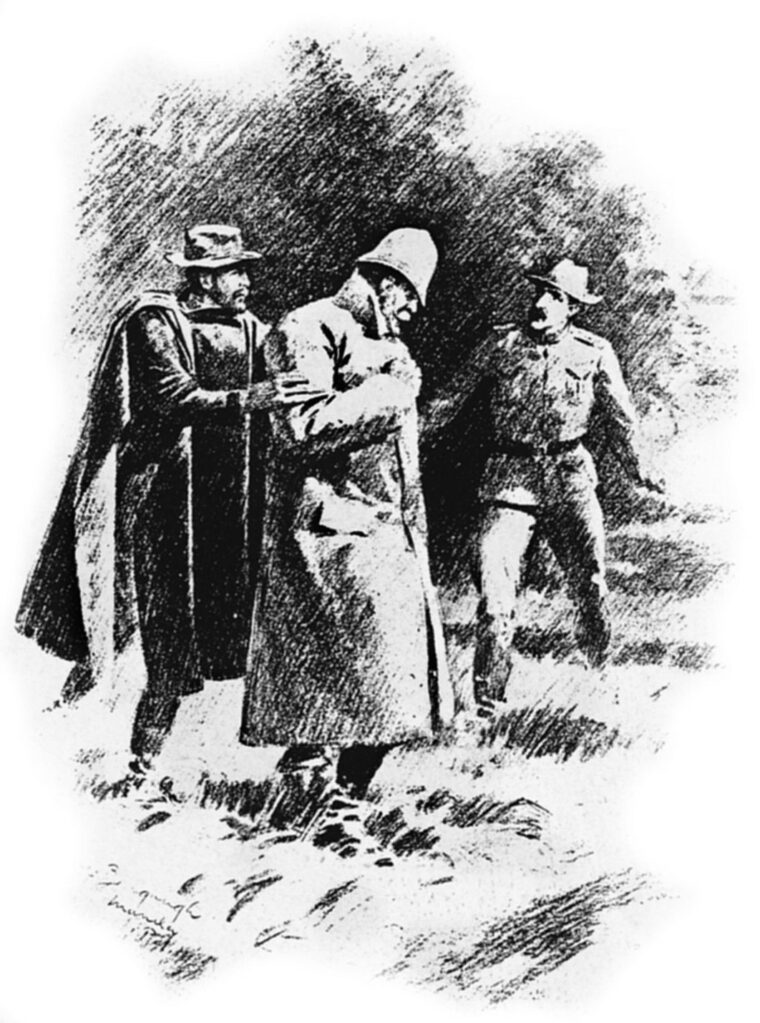

By autumn, Lawton had been placed in charge of the defenses of the capital city of Manila and was pushing the insurgents north when, waiting for Otis’s permission for a major movement, he led a “scout in force” north of the city. On December 18, 1899, accompanied by a correspondent from Harper’s Weekly and leading two squadrons of cavalry and three battalions of infantry from Manila in very heavy rain, Lawton assaulted San Mateo, a long-time nationalist stronghold 18 miles from Manila. There, he was met with only weak oppositon, about 250 guerrillas who were defending the place, and his men took San Mateo easily.

Near the end of the fighting, one of Lawton’s staff officers was shot in the side and fell in an exposed position. Lawton, making a conspicuous target in his bright yellow slicker and his customary pith helmet, ran to the officer’s side and began directing the construction of a litter to remove the lieutenant from the field. As he stood over the wounded man, Lawton suddenly threw up his head, clenched his teeth, and pressed the palm of his left hand against his chest. Asked where he had been hit, he said, “Through the lung,” stood for a few seconds, and then collapsed dead into the arms of his aide de camp.

In a double irony, the sharpshooter who had killed Lawton was under the command of a general named Licerio Geronimo, and the night before Lawton’s death, President McKinley had instructed the War Department to prepare his promotion to major general. Lawton was the highest ranking American officer to fall in battle in either the Spanish-American or Philippine wars.

Henry Lawton Remembered

Secretary of War Elihu Root ordered flags to be flown at half-mast, badges of mourning to be worn, and 13-gun salutes to be fired at every American military post and station. Lawton, he wrote, “leaves to his comrades and his country the memory and example of dauntless courage, of unsparing devotion to duty, of manly character, and of high qualities of command with which he inspired his troops with his own indomitable spirit.”

Theodore Roosevelt, a close friend of Lawton who rode his own fame in the Spanish-American War into the vice presidency and the White House, later remarked that he would have chosen Lawton as his secretary of war had he lived. William Howard Taft, who ultimately was Roosevelt’s choice, later went on to be president in his own right.

Lawton’s body was given a state funeral at Manila, which Harper’s Weekly called “the most imposing ever seen in the city,” before his body was exhumed and taken back to the United States. In San Francisco, an estimated 30,000 people lined the streets to watch Lawton’s funeral procession pass between the harbor and the railway depot, where the body was placed on a train and taken to Washington, D.C. Lawton’s final resting place is Arlington National Cemetery.

A subscription was raised for Lawton’s widow, the former Mary Craig of Kentucky, and she wore black for the rest of her life. Today, the fallen general is remembered through Fort Lawton, near Seattle, Washington, and Lawton, Oklahoma, both of which were named in his honor.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments