By Robert Whiter

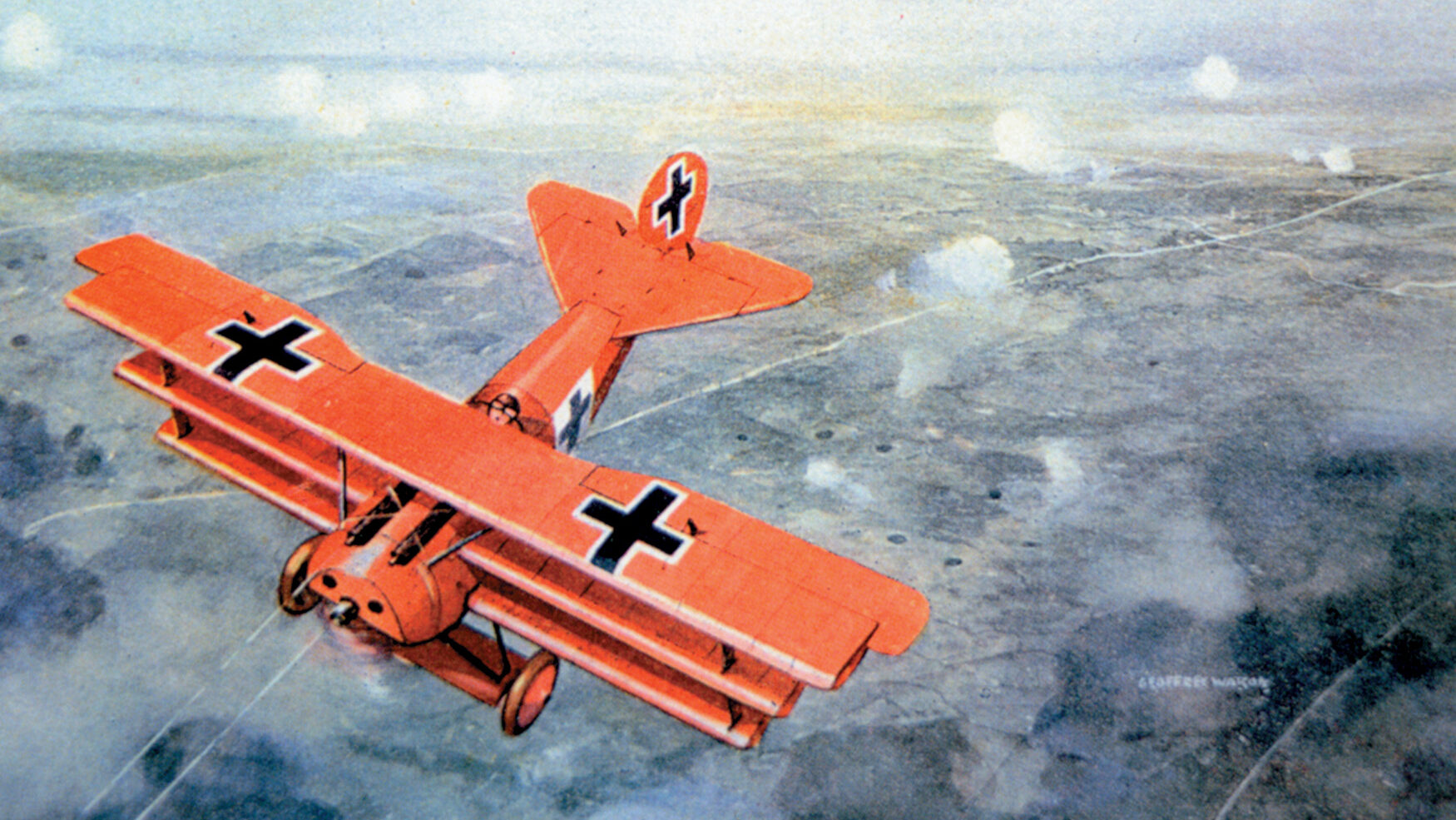

It was early in the year 1917, and a member of the Luftstreiknafte (German Army Air Service), Freiherr (Baron) Manfred von Richthofen, was feeling a trifle disgruntled. He had brought down 16 confirmed enemy planes to date, one of which was piloted by the celebrated British champion, Major Lanoe Hanker, VC, DSO, and credited with at least seven victories. Max Immelmann and Oswald Boelcke (pronounced Berlkeh) had both been awarded the Orden Pour le Mérite after downing only eight or nine Allied airplanes; why had he not received similar recognition?

To add insult to injury as it were, von Richthofen had just received a telegram directing him to take command of the Eleventh Jagdstaffel (literally hunting or pursuit squadron). This would mean leaving all his friends and fellow airmen of the Boelcke Staffel (his own squadron) behind. In addition, the unit to which he was being sent had a bad standing. Despite being formed several months earlier, it had yet to claim an aerial victory.

Two days after receiving the annoying wire, von Richthofen’s comrades arranged a farewell dinner. It was during this celebration that another telegram arrived from headquarters. Guaranteed to bring a smile to the young Prussian’s face, it stated that His Majesty had graciously condescended to give him the Orden Pour le Mérite. Richthofen received the award on January 12, 1917. He said, “My joy was tremendous. It was balm on my wound.”

One frequently hears the Pour le Mérite referred to as Imperial Germany’s highest decoration. This isn’t strictly correct. Actually, Germany by name had no awards as such. It was the various “states”—kingdoms, grand dukedoms, dukedoms, and earldoms, not forgetting the Free Hansa towns of Bremen, Hamburg, and Lubeck—that supplied the many medals and decorations. The Pour le Mérite like the Iron Cross was a Prussian award, but because Wilhelm II of the House of Hohenzollern was not only King of Prussia but also Kaiser (or Emperor) of the German Reich, most of the German officer class regarded it as the supreme honor.

But some did not. In fact, after the Kaiser had conferred the Pour le Mérite on Max Immelmann, the King of Saxony awarded him the Commander’s Cross of the Order of St. Heinrich. To quote Immelmann: “To me as a Saxon the Commander’s Cross is a higher order than the Pour le Mérite.” To prove his point, when Immelmann, the “Eagle of Lille,” posed for a photograph, he wore the Saxon Order around his neck, but placed the Pour le Mérite to a spot just below and to the side. In addition, the Saxon Ritterkreuz (Knight’s Cross) of the same order leads the row of medals on Immelmann’s chest, preceding the Iron Cross (2nd class) and the Hohenzollern House Order with swords, both Prussian awards.

As with many orders, there have been several variations—or perhaps more properly, grades—of the Pour le Mérite over the years. But the one arguably most conferred consists of a Maltese cross enameled blue, edged in gold, with four golden eagles situated between its arms. A golden imperial crown with the letter F for Friedrich was engraved on the upper arm of the cross, with the words Pour le Mérite distributed on the other three limbs. It is suspended by a 2 1/4-inch black-and-white-striped ribbon, the white stripes being woven with silver threads (narrower ribbons have been reported).

The specimen in my collection has the wide ribbon and is suspended by a flattened split-ring that passes through the so-called “pie slice” located at the top of the upper arm. Earlier orders have a metal loop in lieu. The medal was directed to be worn hanging around the neck at all times. That this was carried out to the letter by some recipients is evidenced by the fact that Max Immelmann, Karl Allmenroder, and Wemer Voss, when brought down or crashed, were wearing the decoration in its accustomed place.

When Manfred von Richthofen crashed on March 9, 1917, he was wearing his dirty leather flying jacket and a scarf around his neck. The men and ground officer who rushed up to render help and later took him to the officers’ mess didn’t recognize him. The ground officer asked the pilot if he had ever shot down enemy planes. “Twenty-four,” was the reply. The officer thought the man a liar until he removed his scarf and jacket, revealing the Blue Max. Then von Richthofen’s hosts recognized him. They sent for oysters and champagne with which to toast their new guest.

The order of the Pour le Mérite had its origins in 1667 when it was known as the “Order of Generosity,” and was founded by the Elector of Brandenburg, Friedrich I. It was remodeled on June 6, 1740, by the latter’s son Friedrich, later known as Frederick the Great, and given the title Orden or Ordre Pour le Mérite.

Although the award was strictly to be given to officers for gallantry in war (other ranks or enlisted men receiving the Golden Military Cross—Militar Vedienstkreuz—instituted February 1864 and known as the Pour le Mérite fur Unteroffiziere), there was also a civil division. For this, the ribbon and the gold and blue coloring remained the same, but the badge assumes an entirely different shape. It consists of a circular band in blue, trimmed with gold, and bears the words Pour le Mérite in gold. It has golden crowns at 12 o’clock, 3 o’clock, 6 o’clock, and 9 o’clock, sticking out from the circular band. The middle disc of gold, which contains an embossed imperial eagle, is held in place with eight capital Fs set back-to-back and four IIs set in between. Created by King Friedrich Wilhelm IV in May 31, 1842, it was primarily awarded for distinction in Science and Art. It survived World War I only to be suspended by the Nazis soon after 1933; however, there was a revival in 1952 and it continues to be awarded to this day, albeit sparingly.

A further embellishment could be had for the military variety. This was the addition of the oakleaf cluster (in German, Orden Pour le Mérite mit Eichenlaub). It was instituted in 1813 (the same year as the introduction of the Iron Cross) by Friedrich Wilhelm III. The three oak leaves are affixed to the suspension ring. Furthermore, in 1817 the wide version of the ribbon has another white-and-silver-stranded stripe added to the middle. That this additional honor wasn’t easy to come by is attested to by the Red Baron’s remarks in the officers’ mess on April 6, 1918, 15 days before his death. He and his comrades were celebrating the announcement that the Kaiser had conferred on von Richthofen the third-class order of the Red Eagle with crown and swords. When asked how many orders he would like to receive, the decorated pilot replied, “Every one that I can get. I should especially like to add the oak leaves to my Pour le Mérite, but that is impossible.”

“Why?” asked one of his pilots. Von Richthofen pointed out that even General Ludendorff hadn’t received them despite his exceptional war record. Ludendorff, who had been on the German Imperial Staff, had drawn up the original plan for the attack on the 12 forts at Liege, which were of the utmost importance for Germany’s advance into Belgium. Although not officially a member of Von Emmich’s army, Ludendorff was assigned to work with him and report the progress to the Second Army, commanded by General von Bulow. When the advance was found to be held up, the story goes that Ludendorff placed himself in command of one of the halted formations and boldly led it up to the citadel. Banging on the barred door with the hilt of his sword, the surprised occupants opened it and surrendered en masse; Ludendorff found himself master of the city! Both General von Emmich and Ludendorff were awarded the Pour le Mérite for this operation.

Subsequently, Ludendorff helped mastermind the German triumph at Tannenburg, rose to military head—even de facto dictator—of Germany and drew up the plans for his country’s final—and initially successful—assault in 1918. When this Kaisershlacht (Kaiser battle) was showing promise, the Kaiser congratulated Ludendorff and presented him with a small statuette of himself, but no oak leaves were to be forthcoming.

In 1844 Friedrich Wilhelm IV issued a decree that “anyone who had held the award [Pour le Mérite] for 50 years was entitled to adorn it with a gold imperial crown; this would be attached to the suspension ring.” The victor of Sedan, General Feldmarschall Graf Helmuth von Moltke was awarded the crown in 1889; it was encrusted with diamonds.

In 1866, Wilhelm I created the Gross Kreuz or Great Cross, together with a diamond-shaped golden breast star. The enlarged badge was relieved in the middle by a gold disk containing Frederick the Great’s likeness in profile, the latter being repeated on the breast star with an added circular blue border containing the legend Pour le Mérite. It is said to have been created as a reward for the victors of the Battle of Koniggratz, namely Wilhelm’s son Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, and his nephew, Prince Friedrich Karl of Prussia. This battle saw the termination of the Seven Weeks’ War against Austria, an armistice being signed at Nikolsburg on July 22, 1866.

At the urging of his generals, the King himself accepted the Great Cross. Although this supreme class of the Pour le Mérite could be upgraded with oak leaves as far as can be ascertained, only the previously mentioned princes seem to have received them, the occasion being for their participation in the 1870 Franco-Prussian War.

No one is quite sure how the Orden Pour le Mérite came by its sobriquet the “Blue Max.” The most likely explanation is that it derived from Max Immelmann, the “Eagle of Lille,” an early recipient of the blue Maltese cross during WWI. In spite of extensive research over the years, I have found no reference to the name “Blue Max” before the 1914-1918 conflict. Incidentally, Major James McCudden, VC, had another nickname for it. On speaking of the death of Werner Voss, McCudden referred to “the Boolcke collar,” likely after recipient Oswald Boelcke.

In their excellent book German Knights of the Air (1914-1918), Terry C. Treadwell and Allan C. Wood offer another interesting theory: “The Germans pronounce the word Maltese as Maa’ltese; if this word is then corrupted to ‘Maa’ and the word ‘cross’ is replaced by an ‘X’, then the term ‘Blue Max’ can be derived.”

A question one often hears is, “Why did a Prussian order bear a French title?” Here’s the reason. At his court, Frederick the Great commanded that only French fashions and language be used. Hence, Friedrich’s palace at Potsdam was named Sans Souci, the crack cavalry regiments had the title of Garde du Corps, and his distinguished medal was inscribed with the words Pour le Mérite. It is said that Friedrich was of the opinion that the German language was fit only for stable boys.

Although it would seem that the WWI pilots of the German Air Service secured a good percentage of the Ordres Pour le Mérite, other services had their fair share. For example, the German Naval Air Service, which supplied the officers and men that crewed the Zeppelins, also garnered several of the blue and gold crosses. Peter Strasser, Joachim Breithaupt, and Treuch von Buttlar-Brandenfels all participated in air raids against the United Kingdom and were awarded the coveted order.

Two well-known names from the German Navy Submarine Division were awarded the Blue Max. These were Walter Schwiege, the man who sank the Lusitania; and the U-Boat ace of aces, Lotha von Arnauld de la Perière, who sank 400,000 tons of Allied shipping.

On studying the records of the men who received the Pour le Mérite, one comes to the conclusion that, on the whole, the decoration was awarded more for continuous brave service than for one supreme act of valor. That this differs from the U.S. Medal of Honor or Britain’s Victoria Cross is clear from the citations.

For the medal collector, the Orden Pour le Mérite is a rare and costly item. I count myself very lucky on being able some years ago to pick up my own specimen at a reasonable price. The last one I saw for sale was at a Highland Games gathering. The vendor was asking $1,800. In passing, perhaps it is worth mentioning that there are some very good copies on the market. As the old saying goes, “Caveat Emptor.”

When the Kaiser relinquished the thrones of both Prussia and Germany in 1918, the military division of the order also came to an end; there were no more awards. But, at military meetings and reunions, those entitled to wear the order did so. There are photographs taken even as late as the 1970s showing recipients still wearing their “Blue Max” with pride.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments