By Phil Zimmer

Promoted to full colonel in the German Army and an award of the prestigious Knight’s Cross were significant accomplishments, even in the waning days of World War II. Yet, Lt. Col. Heinrich Scherhorn managed to get the promotion and the Knight’s Cross while languishing well behind the lines in a Soviet prisoner of war camp, and his promotion was fully aided and abetted by his Soviet captors.

Operation Berezino

The Soviets had deceived the Germans into believing that Scherhorn had rallied a group of some 1,800 German soldiers who were behind enemy lines in Belorussia and surrounded near the Berezino River in the summer of 1944. The group was reportedly making a determined yet desperate attempt to reach German lines. The report was based, in part, on truth. However, Soviet forces had earlier destroyed the unit near Minsk, with Scherhorn and 200 troops taken captive. The Soviets seized upon the opportunity, knowing that the Germans already believed that some Wehrmacht soldiers were stranded in the forests near Berezino.

Before Operation Berezino was over nine months later, the hard-pressed Germans had been convinced to fly 39 sorties to the fictitious fighters, dropping 13 radio sets and 225 cargo packs consisting of ammunition, food, medicine, and more than two million rubles, according to Robert W. Stephan, a former CIA counterintelligence specialist. In addition, 25 German agents and intelligence officers were rounded up in the successful deception, adds Stephan, author of Stalin’s War: Soviet Counterintelligence Against The Nazis, 1941-1945.

As the Germans slowly took the bait, the Soviets further added to the ruse, with the trapped unit supposedly growing nearly 40 percent in size, including 16 officers—all quietly captured earlier—and 884 wounded. This supposed growth, in turn, created the need for even more medicine, ammunition, and supplies.

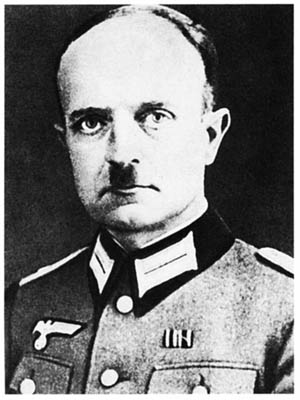

Heinrich Scherhorn was captured by the Soviets and used to help deceive the Wehrmacht into

believing that he led as many as 2,500 German troops behind Soviet lines.

“The German sense of duty, and the potential political and military value of rescuing 2,500 troops trapped behind Soviet lines, proved stronger than the suspicions surrounding the operation,” reports Stephan. Despite some serious doubts and rapidly depleting resources, the Germans continued to supply food and ammunition to the nonexistent unit. Whenever the Germans asked detailed questions about various officers supposedly working with Scherhorn, the Soviets would isolate them and obtain the information requested by the Germans.

Luck certainly played a part when a German intelligence officer landed on a primitive airfield to meet Scherhorn. The excited Oberleutnant Barfeldt jumped out of the aircraft a bit too early as it was taxiing, and a propeller blade decapitated him. The rattled crew quickly recovered the body and flew off, perhaps saving Operation Berezino from being uncovered.

32 Officers, 250 Servicemen

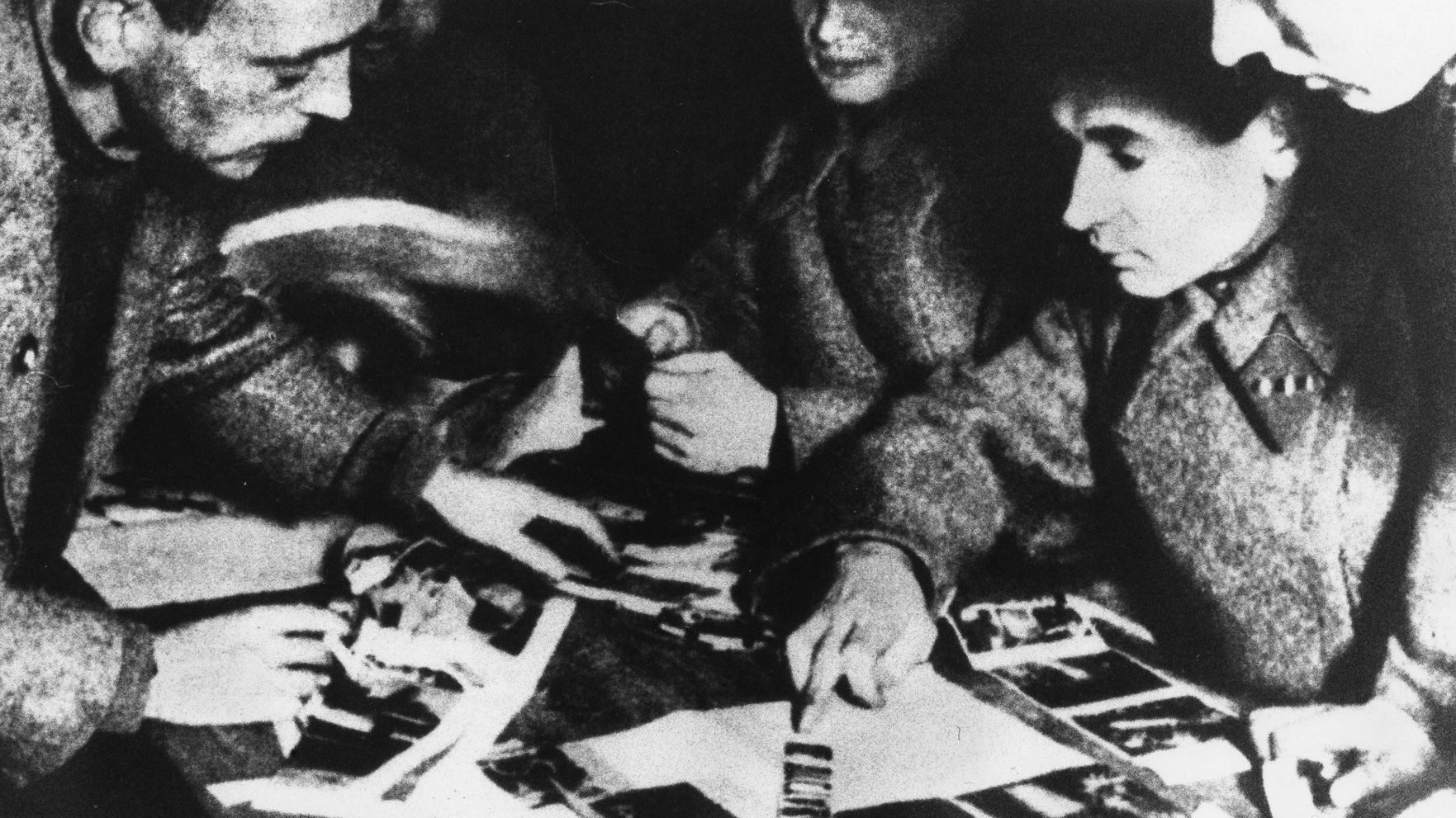

The Soviets invested considerable resources to Operation Berezino, including 32 intelligence officers and more than 250 servicemen. These included high-ranking Leonid Aleksandrovich Eitingon, who had earlier coordinated the assassination of Leon Trotsky, Stalin’s political rival. A number of POWs were pressed into service to create a convincing camp, complete with dugouts and tents to further convince the Germans.

Adding even greater authenticity to the troops’ predicament, Soviet counterintelligence convinced the Germans that some of the planned airdrops needed to be postponed because of approaching enemy troops. The Soviets even managed, according to reports, to have the cooperative Scherhorn initially talk with recently dropped German parachutists who radioed back that everything was as stated. The fresh Germans were then captured by NKVD (Soviet Intelligence) security troops hidden nearby.

The Soviet deception skills had developed to the point that they were able to continue the ruse for nine months while convincing their wily opponents to supply ammunition and food desperately needed elsewhere.

Operation Barbarossa’s Devastation

The Soviets had come a long way since the early phase of World War II when the Red Army was overwhelmed and scattered as the powerful German Wehrmacht rolled across the Motherland in June 1941. The advancing Germans had swept down on the town of Orel, only 200 miles from Moscow, so quickly that they found the trams still running. The Wehrmacht moved so fast that within a few months the invaders were at the gates of Moscow and Leningrad, threat- ening the very existence of the Soviet Union.

More than three million Axis troops had invaded the Soviet Union, organized in 146 German divisions along with 14 Romanian divisions in the south and Finnish units in the north. They were supported by more than 2,000 aircraft and 3,300 tanks.

The Soviets had been caught flat footed, nearly totally surprised. Soviet aircraft were exposed and lined up “in inviting rows at major air bases,” notes British historian Richard Overy. Many forward units had limited ammunition, and within the first month 200 out of 340 military supply depots fell into German hands.

By the end of December 1941, some 3.8 million Soviet prisoners had been taken and were stranded behind barbed wire in desperate conditions. Perhaps a million more had been killed. Leningrad, Russia’s old imperial city, was surrounded, and the lack of food began to take its toll. The city’s death rate rose to 5,000 per day during that first winter of the epic siege. Moscow itself teetered on the verge of collapse with many of the government offices evacuated to Kuibyskev, some 500 miles to the east.

Even Lenin’s body had been whisked from Moscow, and Stalin himself had a special train on standby, but he decided at the last moment to remain in the capital city. His decision to stay helped calm the populace of Moscow, which had seen widespread looting and civil unrest.

The Germans had overrun some 40 percent of the Soviet Union’s population and nearly the same percentage of its production capacity. Only 90,000 Soviet troops stood between the Wehrmacht and Moscow, which was so close that some German troops reported seeing the city’s spires.

Soviet Maskirovka

Stalin, in many ways, was like a prize fighter who had been knocked into his own corner. He and his comrades were dazed by the onslaught, but the decision had been made to stand and fight. The coming of winter certainly played a significant role in halting the German tide, as did information from a well-placed Soviet agent in Japan. The spy had informed Moscow that Japan had set its eyes on potential oil-rich war prizes to the south, rather than Soviet territory. Based on that information, Stalin moved winter-hardened Siberian units across the length of the Soviet Union to successfully shore up the defense of the capital.

Soviet military leaders had long held that maskirovka, or military deception, was a viable weapon in protecting the Motherland. They had believed firmly in Sun Tzu’s centuries old contention that “all warfare is based on deception.”

It was, perhaps, during the fighting for Moscow that the Soviets first demonstrated their affinity for maskirovka. The overly confident German commanders unwittingly assisted the effort. The Germans had convinced themselves that the Soviets had depleted their reserves. They further failed to realize that elements of three Soviet armies, including the experienced Siberian troops, had been redeployed around Moscow under a new commander, General Georgy Zhukov. Those Russian armies would serve as the shock troops to spearhead the early December 1941 Red Army counteroffensive before Moscow.

Bad weather, the repositioning of troops at night, and comparatively crude maskirovka efforts assisted in catching the tired and overextended Germans by surprise. The Germans were successfully pushed back, giving the Soviets a much-needed respite as winter fully closed in on the opposing forces.

“At best, Soviet experiences at Moscow partially indicated what could be done with maskirovka,” noted David Glantz, author of Soviet Military Deception in the Second World War. “Moscow was only their first lesson in a long combat education.” Successful early deception efforts prompted the Soviet high command to consider an even broader range of deceptive moves that could contribute to future operations.

The Soviet Counterintelligence Advantage

The Germans did have some successes with their own military deceptions. An operation that began in Warsaw in the summer of 1943 lasted nearly a year. It led to the capture of 52 Soviet agent teams and enabled the Germans to determine the scope of some Soviet military operations in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Upper Silesia during that time frame.

However, as the war progressed so did Soviet sophistication in the use of deception. Basic practices such as false and misleading radio traffic, camouflage to conceal troops and equipment, and fake troop movements gradually gave way to more complex, coordinated, and sophisticated measures such as Operation Berezino.

The Soviets had a number of advantages over their German opponents when it came to deception. Russian-born American journalist Issac Don Levine summed up the Soviet system well in 1960. The government was “esstentially a counterintelligence apparatus. It was conceived in 1903 by Lenin as an operation in counterintelligence against the Czarist regime, and it remained a conspiracy ever since…. It was a front…,” with real power resting with the Communist Party.

The Soviet Union from its very inception was “designed from top to bottom to catch, manipulate, kill, or imprision ‘spies,’ ‘traitors,’ and dissidents of every stripe, real or imagined, to keep the Communist party in power,” observes Stephan.

German arrogance and hubris in dealing with the untermenschen or “subhuman” Slavs also played into the hands of Soviet counterintelligence officers. The time-proven Soviet system of suspicion made it difficult for German spies to operate behind the lines and collect valuable information. In fact, if more than 10 percent of German agents completed their assignments behind Soviet lines, the Germans were pleased.

Making things even more difficult for German agents was the fact that Soviet soldiers were required to carry five to 10 different documents, including identification, pay book, and military orders. Civilian truck drivers needed a bill of lading, title, travel orders, and a weapons pass if carrying a weapon. To confound German agents, the Soviets ingeniously used a type of rusting wire that was not available outside the country for staples. The Soviets even printed some documents on wallpaper not available outside the Soviet Union.

Soviet counterintelligence closely examined the uniforms of suspected agents. Uncovered buttons on the underwear of German agents posing as Soviet officers would raise eyebrows because Soviet officers wore covered buttons on their underwear. Even the number of bullets issued to pistol-carrying officers could raise questions, with the Germans most often supplying 20 cartridges to agents while Soviet officers carried 21 cartridges to reload their Nagant pistols three times.

Recruiting Double-Agents

The Soviets were adept at not only capturing German agents, but also in turning them against the Germans. They were even able to plant double agents inside the German system. One agent, Ivan Savchuk, worked himself into a position serving as an interpreter for German intelligence screening of Soviet POWs for potential agent candidates. He managed to provide the Soviets with detailed information on 80 agents and 30 Abwehr (German intelligence) staff officers.

The Soviets also managed to infiltrate Abwehr spy training schools, with some agents actually becoming instructors. Information supplied by one such instructor alone resulted in the apprehension of some 112 German agents. At one time, Soviet counterintelligence officials were so emboldened that they actually instructed their agents to contact them by using the radio facilities at the German training schools.

Maskirovka in Operation Bagration

By mid-war the Soviets had fully mastered radio discipline and communications security. Camouflage techniques had progressed significantly, and the Soviets had largely mastered the difficult task of quickly relocating troops to take advantage of German weak points. Zhukov noted that by that time the Soviets were much better at keeping their intentions secret and at spreading disinformation and misleading the enemy. By then most Soviet units were using code tables in all radio and telephone transmissions. Codes were being changed every 24 hours, and cipher keys were being transmitted only by courier. An extremely detailed maskirovka component was included in each operational plan.

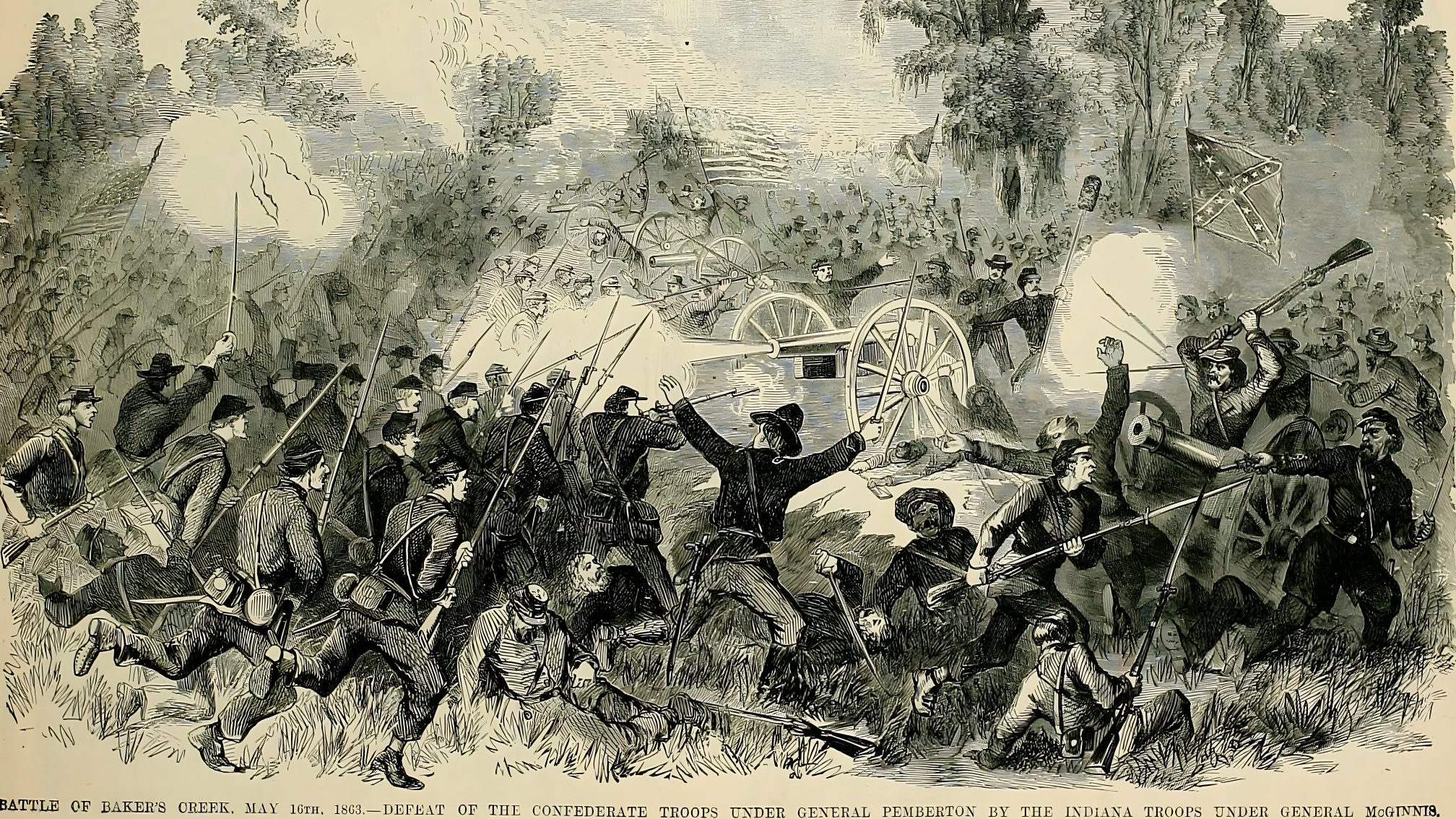

In Belorussia, as part of Operation Bagration in mid-1944, Soviet tanks and guns rolled out of the swamps on the northern edge of the Pripet Marshes, surprising German defenders. Undetected by the Germans, Soviet engineers had laid wooden causeways, creating makeshift roads for the Soviet armor that made gains of 25 miles per day against the startled Germans, who dropped back against the remorseless onslaught.

The planning of Operation Bagration was kept so secret that the Soviets were able to have partisans strike German Army Group Center’s key transportation points. Deception efforts had encouraged the Germans to reinforce the southern sector of the front while the decisive blow hit in the north. The destroyed railroad lines meant that the Germans could not easily redeploy their armor where it was most needed.

The two-month operation decimated Army Group Center, isolated Army Group North, and resulted in the loss of 450,000 German fighting men. It was perhaps the single largest German intelligence failure of the war, with the direction of the main thrust initially missed and Soviet strength underestimated by some 1.2 million men.

False orders, rumors, and feints played important roles in confusing the Germans. A number of German agents were turned by the Soviets prior to and during Operation Bagration, further aiding subsequent Soviet deception efforts.

Before Operation Bragration was over, the Soviets had advanced some 450 miles, liberating Belorussia and eastern Poland. The Soviets then focused on the southern sector, where the Germans had believed the first blow would fall. In late August, Army Group South collapsed. By September 2, Bucharest had fallen and the Ploesti oil fields, Germany’s last major source of oil, were in Soviet hands.

Eliminating Enemy Spies and Preserving the Regime

The Soviets had clearly mastered maskirovka, substantially confounding German intelligence, which often underestimated Soviet strength by 25 to 40 percent. Soviet counterintelligence had achieved its two primary objectives during the war: elimination of enemy spies and the preservation of the regime itself. At the end of the war, Stalin remained in power, and the Soviet Union was well on its way to becoming a superpower.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who had staunchly opposed the Soviet Communists for years prior to World War II, astutely summed up the situation in March 1944. He stated: “Not only have the Hun invaders been driven from the lands they had ravaged, but the guts of the German army have been largely torn out by Russian valor and generalship.”

Wartime hyperbole set aside, Churchill’s comments continued to be proven correct, right up to the time that German forces surrendered and the war ended. Soviet blood and maskirovka turned the tide in the East and helped achieve Allied victory in World War II.

Phil Zimmer is a former newspaper reporter and U.S. Army veteran. He holds a bachelor’s degree in history from SUNY Fredonia and a master’s degree in journalism from Penn State University. He resides in Jamestown, New York.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments