By Kevin Seabrooke

Mariya Oktyabrskaya was a Soviet Ukrainian tank driver and mechanic who fought on the Eastern Front against Nazi Germany during World War II.

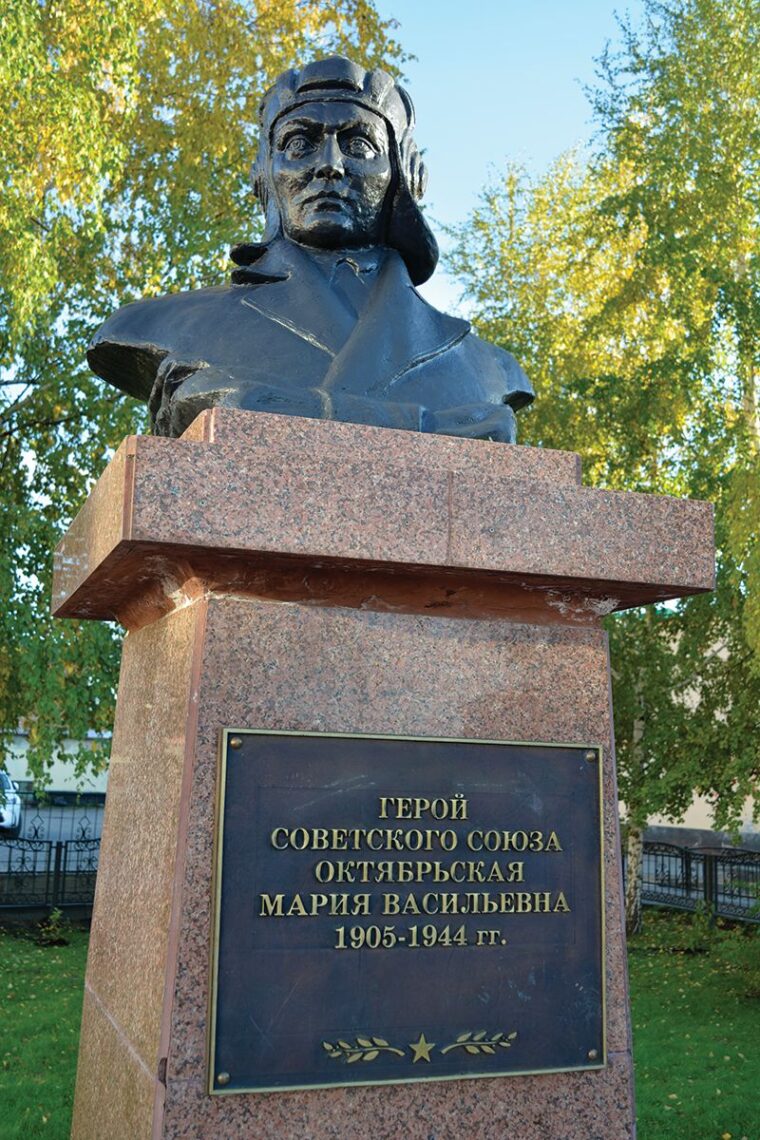

Her courage and devotion to the Russian war effort would make her the first female tanker to be named as a “Hero of the Soviet Union,” the U.S.S.R.’s highest military honor for bravery in combat. She was also awarded the Order of Lenin.

One of 10 children, Mariya Vasilyevna was born into a peasant family around 1905, in Kiat, Taurida Governorate, Russian Empire (Southern Ukraine today, near Crimea). After finishing school, she worked in a cannery in Simferopol and then as a telephone operator.

In 1925, she married a calvary school cadet, Ilya Fedotovich Ryadnenko. The pair adopted the name Oktyabrskaya—”October,” an allusion to the Oktyabrskaya Revolyutsiya or October Revolution. By all accounts Mariya enjoyed being the wife of a Soviet Army officer and got involved in the “Military Wives Council” and trained as a nurse in the army.

“Marry a serviceman, and you serve in the army: an officer’s wife is not only a proud woman, but also a responsible title,” She reportedly said.

She also learned how to use weapons and drive vehicles. She even earned the honorary badge of “Voroshilov’s Shooter,” from a society formed by Marshal Kliment Voroshilov in 1932 to train civilians as a kind of civilian reserve force that would eventually grow to 41 battalions.

When the eastern front of World War II opened with Germany’s push toward Moscow in June 1941, Mariya was evacuated to Tomsk in Siberia, where she again worked as a telephone operator.

Two years later, the news came that her husband had been killed fighting the Germans near Kyiv in August 1941.

Enraged, she was determined to fight the Germans to avenge her husband’s death. She went to the enlistment office and requested to be sent to the front, but was rejected. She was deemed unsuitable for combat because she had spinal tuberculosis, also known as Pott’s disease, which can lead to the collapse of the vertebrae.

She sold all of her and her sister’s possessions to donate toward the building of a T-34 tank for the Red Army. With whatever savings benefits she had as the widow of a regimental commissar, along with embroidery work she did on the side, she reportedly managed to raise 50,000 rubles, which she donated to the national defense fund.

She then reportedly sent a telegram to Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin expressing her desire to avenge her husband by killing “fascist dogs” and asking to be allowed to drive the T-34 medium tank she would call “Fighting Girlfriend” (Боевая подруга). Perhaps thinking it was good propaganda, the State Defense Committee agreed to this.

By this time, Oktyabrskaya was 38 years old. She enrolled in a new five-month tank training program at Omsk Tank Engineering Institute immediately after the donation. Before this, manpower shortages had meant that most tank crews were rushed straight to the front line with minimal training. She was then posted to the 26th Guards Tank Brigade, part of the 2nd Guards Tank Corps, as a driver and mechanic

Though women made an enormous contribution to the war effort for both the Axis and the Allies, relatively few were directly involved in combat. Nearly 200,000 women in Britain, mostly through the Auxiliary Territorial Service, were involved in many military roles traditionally held by men and were recruited as radar operators, as well as spotters on anti-aircraft gun crews. Neither the Brits, the Germans or the U.S. were comfortable with women pulling triggers.

American women also replaced men in manufacturing and many other roles during the war. In order to free up male pilots to fight overseas, some 1,100 civilian women also volunteered for the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) program to ferry planes—even the big B-26 and B-29 bombers—from factories to bases and between bases. The expectation was that WASPs would become an official part of the military, but the program was canceled after two years. (The WASPs were finally given veteran status in 1977, the same year the U.S. Air Force Academy graduated its first female pilots).

As in the Allied countries, German women worked in auxiliary positions: administration, manufacturing, agriculture, ferrying aircraft. It was prohibited to train women on the operation of guns, lest they become a “gun woman” flintenweiber—like the Red Army women depicted in official Wehrmacht propaganda as the “evil” other, hated by German soldiers as a challenge to the social and gender order.

In France and Greece, and everywhere the Nazis invaded, women played vital roles in partisan fighting and underground networks.

At first, communist Russia also prohibited women in combat. After Operation Barbarossa—the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union—began on June 22, 1941, thousands of women volunteered to fight, but were turned away. Women were only allowed to serve in medical and auxiliary units. There was one exception to this rule—Stalin’s secret Order No. 0099, issued October 1941—permitting the formation of three women’s air regiments by that December.

Much has been written about one of those three, the 588th Night Bomber Regiment that became famous as the “Night Witches”—a nickname given to them by the Germans (Nachthexen), who could hear the rush of air through the the struts of the obsolete canvas and plywood Polikarpov Po-2 biplanes, as the pilots cut their engines to glide over the target. Of the 95 women to earn the distinction of Hero of the Soviet Union, 30 were members of the women’s air regiments. Though the Soviets would publicly deny that they were mobilizing women soldiers up until 1944, the Night Witches once flew 324 sorties in a single night and more than 24,000 combat missions over the course of the war.

By 1942, the Party Central Committee decided to allow women volunteers in combat, no doubt influenced by the fact that by then 4.5 million Soviet soldiers were killed, captured or missing. Ultimately, some 800,000 women served in the Red Army during the war, making up about five percent of Soviet Armed Forces. The majority of women serving at the front lines were medics and nurses. But by 1945, some 246,000 women were in combat roles as snipers, machine-gunners, partisans and even paratroopers. Nearly 200,000 women were decorated, including the 95 of them who received the Hero of the Soviet Union.

Also famous were the more than 2,000 Soviet women snipers, none more so than “Lady Death,” Lyudmila Pavlichenko, who had 309 confirmed kills. Most of those came at the sieges of Odessa and Sevastopol in 1941-42. After she was wounded a fourth time, Lt. Pavlichenko was sent to the U.S. on a propaganda tour to drum up support for the Soviet Army fighting the Germans on the Eastern Front. On the trip she became the first Soviet citizen to visit the White House.

Women in tank crews were much less well known, though one, Aleksandra Grigoryevna Samusenko, actually commanded a T-34 tank. Another, Alexander(ra) Rashchupkina, posed as a man to serve as a tank driver from 1942-45. Her secret was only revealed when she was seriously wounded. There was a scandal, but Raschupkina received the Order of the Red Star as other medals.

Mariya had been the first woman graduate from the new tank training program, just ahead of Aleksandra Samusenko. By October she was already on the front lines of the Soviet’s Western Front.

As the driver and mechanic of Fighting Girlfriend, Mariya shared the cabin with Commander Piotr Chebotko, gunner Guennádiy Yaskó and radio operator Mikhail Galkin.

She saw her first action in the city of Smolensk, along the Dnieper River on October 21, 1943. The Red Army had retaken the city, but there were still pockets of resistance. Mariya drove the tank throughout the intense fight in which she and her fellow crew members destroyed machine-gun nests and artillery, as well as any German soldiers they could find.

When her T-34 was damaged, Mariya jumped out to make repairs under heavy fire. Though she had disobeyed orders by doing so, she was promoted to sergeant. For her fellow crew members and any others who had thought Mariya had gotten where she was strictly as a propaganda stunt, there was no longer any doubt about her toughness or capabilities.

Just about a month later, Soviet forces took the town of Novoye Selo in the Vitebsk region of Belarus in a night battle on November 17-18. Mariya’s reputation for toughness and courage grew after her tank was disabled by a German artillery shell to one of its tracks. She and one of the crew climbed down to fix the track while the rest provided covering fire from the turret. Repairs made, “Fighting Girlfriend” was able to rejoin its unit a few days later.

Her second round of mechanical repairs under fire did not rattle Mariya, who still burned for revenge against the Nazis.

She reportedly wrote a letter to her sister, exclaiming “I’ve had my baptism by fire. I beat the bastards. Sometimes I’m so angry I can’t even breathe.”

Two months later, on January 17, 1944, Mariya took part in another night attack, also in the Belarus region, in the village of Krynki near Vitebsk. She drove through German defenses, knocking out machine-gun nests and taking out defenders in trenches. Her T-34 reportedly took out a German self-propelled gun before, once again, it was hit in the tracks—this time by an anti-tank shell. Amid heavy small arms and artillery fire, Mariya characteristically jumped quickly out of the tank and made the repairs. But her luck had run out. She was knocked unconscious when shell fragments struck her in the head. She was taken to a Soviet military field hospital near Kiev after the battle and then to a military hospital in Smolensk. She never regained consciousness. In a coma for two months, she died on March 15, and was buried with military honors at the Heroes Remembrance Gardens in Smolensk.

The crew of the “Fighting Girlfriend” kept fighting and made it to Victory Day on May 9, 1945. After the original “Fighting Girlfriend” was destroyed, the crew went through several replacement tanks —all with the same name as a tribute to Oktyabrskaya—until they reached the Baltic Sea near Königsberg at the end of the war.

In August 1945, Oktyabrskaya was recognized as a Hero of the Soviet Union.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments