By Eric Baker

What set the original Call of Duty game apart from other first-person shooting games set during World War II is the feeling it delivered that the player was just a small part of a much larger battle. Which, since players were taking the role of an enlisted rifleman in some of the war’s biggest battles, they were. Call of Duty 2, for the PC from Activison, captures this feeling even better, with more computer-controlled characters on the screen, both allies and enemies. At the same time, the computer AI doesn’t let the player hang back. It responds to the player being inactive by becoming more aggressive. Particularly with grenades.

In addition to more people, CoD2 also adds vehicles to the game, both the single player and the on-line multiplayer. These additions take place on larger battlefields. The single-player game has the same open-ended scenario selection as the first game. Players can start in Normandy, Russia, or the African desert. No matter where the fight takes place, it turns out that one of the most welcome additions is the ability to lay smoke, which not only keeps the character alive, but also adds to the “yikes” factor of the game when the character suddenly comes on the enemy in the midst of the billows.

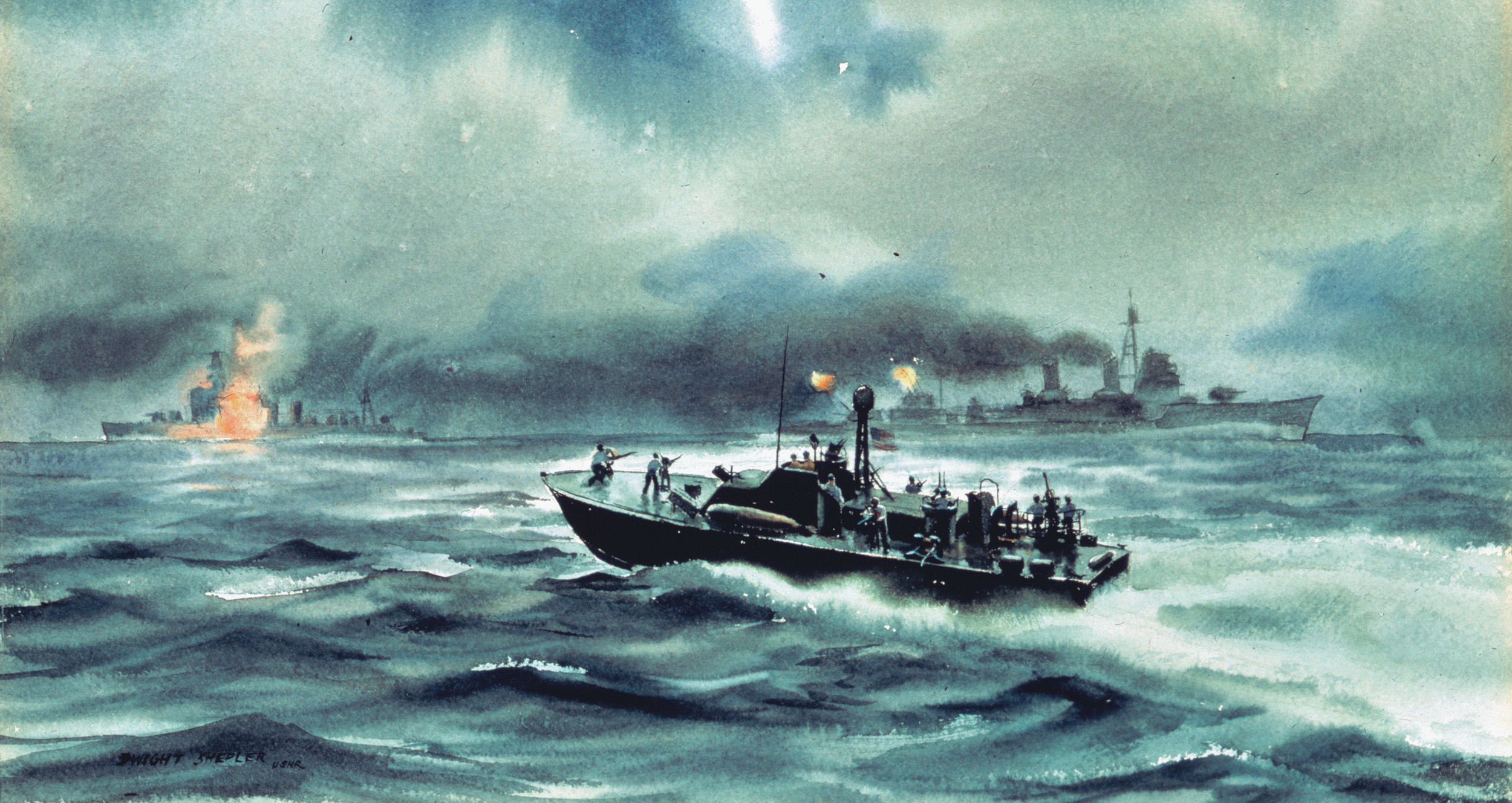

In contrast to the ground-pounding action of CoD2, Heroes of the Pacific, for the PC, PS2, and Xbox and also from Activision, is a highflying game that puts players behind the joystick of a warplane battling above the Pacific. The game starts with the attack on Pearl Harbor and carries on through the major battles of the Pacific, including Wake, Midway, and the Coral Sea. Overall, the game contains ten campaigns and 26 missions. The missions take in the full range of air combat in the era including patrol, attack and defense, ground support, and bombing, both dive and torpedo.

Players can ultimately choose from 35 different planes in HotP. The game can track over 100 planes in combat at a time, which in addition to the highly detailed ship models that appear in many missions, means that combat is very immersive. Players can choose if they want to fly and fight arcade or historic style, and they can choose the difficulty of the missions. The AI wingmen do a decent job during the single-player missions, but the experience of the multiplayer game with real humans “flying” is definitely superior.

A final game worth mentioning is Lost Battalion’s naval-themed card game, Battlegroup: 1939-1945. The game comes with an Allies and an Axis deck, plus an action deck and dice. The game is a historical simulation of WWII ship combat only in the broad sense that the ships and planes on the cards, and the statistics derived for them, are based on the historical units. The rules of the game reflect the realities of that combat, but because of the way the cards are drawn by the players, it is possible to have ships acting together and opposing each other who were never near one another during the war.

Historical limitations aside, Battlegroup is easy to learn, easy to teach, and fast to play. There are rules for two, three, and four players, and players who want to win have to know or learn the roles of their ships and planes, balancing their strengths and weaknesses just as the historical admirals did. Send the planes to attack or keep them to defend? Attack at night without air cover at all? In addition, the victory conditions change with the cards played so that simply sinking the most tonnage is not always the way to win.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments