By Eric Hammel

Backstory: In the first installment, after heroically performing close air support missions for their Marine infantry brethren during several island invasions in 1944, U.S. Marine dive bombers and fighters, eclipsed by carrier-based Navy aircraft, found themselves without a mission. But U.S. Army forces, engaged in the invasion of the Philippines, were in desperate need of support and thus welcomed the dark-blue Corsairs of Marine Air. (Read the First Installment)

The second phase of Marine Air operations in the Philippines began on December 30, 1944, when the four Vought F4U Corsair squadrons of Colonel Zebulon C. Hopkins’s MAG-14 (Marine Aircraft Group 14) were ordered to fly to Samar from Bougainville by way of Emirau, Owi, and Peleliu.

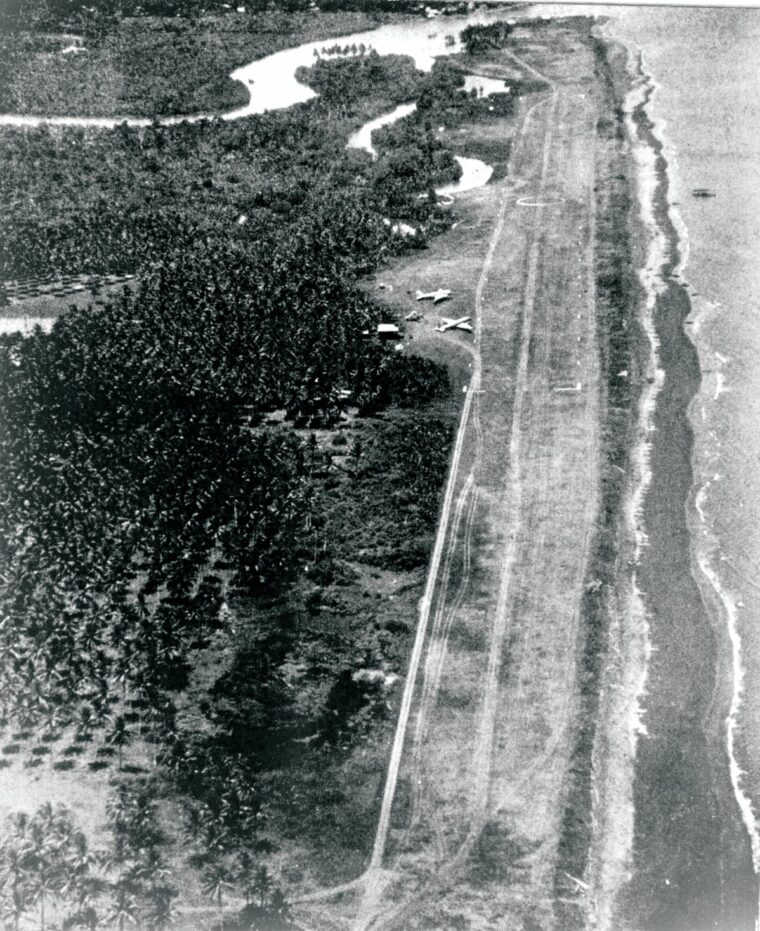

The group had been awaiting this order since December 7, 1944, when it was alerted for the move pending the completion by two U.S. Navy Seabee battalions of a brand-new fighter strip at Guinan, in southeastern Samar. The Marine fighter group was to operate from Guinan in support of operations on Luzon by the U.S. Sixth Army, which was just days away from mounting an amphibious invasion.

The first MAG-14 squadron to depart Bougainville for Guinan was Marine Observation Squadron (VMO) 251 which, despite its designation, was a full-fledged fighter unit. The squadron left Bougainville on December 30 and completed the journey on January 2, 1945, one day before a pre-invasion bombardment force sailed into the Luzon area to begin softening targets around the Lingayen Gulf landing beaches. (Among the many carrier-based squadrons involved in the pre-invasion bombardment were VMF-124 and VMF-213, which were embarked aboard the fleet carrier USS Essex—the first Marine aviation units to be so employed in combat.) The remaining MAG-14 F4U squadrons—VMF-212, VMF-222, and VMF-223—would arrive at Guinan over the next two weeks.

In addition to MAG-14, the ground echelons of two other Marine air groups—MAG-24 and MAG-32—were also prepared to displace from the Solomons to the Philippines. Both of these groups were equipped with Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers, and both had been trained in the newly updated art of close air support. Nevertheless, though the ground crews were on the move and the airmen were considered fully trained, no one knew precisely where the two Dauntless groups would end up. It was not even certain, as the invasion fleet closed on Luzon, that the groups would be deployed there. Indeed, the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing headquarters had been alerted for a move to the Philippines, but it was not certain by the first week of 1945 where it would set up shop.

Of all the Marine aviation units slated for service in the Philippines in early 1945, only the two F4U carrier-based squadrons and the F4U squadrons operating with MAG-12 actually took part in the run-up to the invasion. MAG-12 had been operating on Leyte throughout the conquest of that island, and thereafter it operated with Army Air Forces squadrons of the Fifth Air Force (to which it was attached) in running strikes against lines of supply and transportation targets in the northern Philippines, including Leyte.

By late December, in fact, MAG-12’s four F4U squadrons were so well integrated into the V Fighter Command operational structure that they were usually used interchangeably with Army Air Forces Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk and Lockheed P-38 Lightning squadrons for a wide variety of missions—from combat air patrol to low-level ground attacks against all manner of targets. MAG-12 F4U pilots had been very active—and successful—in air-to-air combat during the Leyte campaign, and they and their fellow V Fighter Command fighter pilots had just about wiped out the Japanese air capability in the Philippines by the end of 1944.

The first confirmed aerial victories awarded to Marine Corps airmen in 1945 went to an F6F night fighter pilot from VMF(N)-541, an element of which had been operating with MAG-12 throughout the Leyte campaign. Between 7:15 and 7:20 am on January 3, 1945, 2nd Lt. Harold Hayes, Jr., downed two A6M Zero fighters while on patrol between Luzon and Negros Islands. These were Hayes’s third and fourth (and last) victories of the Philippines campaign.

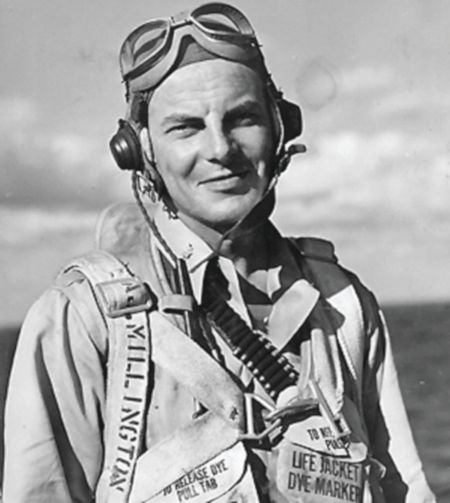

Later that morning, at 9:40, Lt. Col. William Millington, the VMF-124 commanding officer, downed an Imperial Navy P1Y twin-engine bomber over Kagi Airdrome, Formosa, during preliminary air strikes aimed at thwarting a Japanese effort to reinforce the Philippines air bases still in their hands. Millington was the first pilot of the war to down an enemy airplane while serving with a carrier-based Marine aviation unit.

The Japanese high command in the Philippines reacted to the approach of the Luzon invasion fleet with its second kamikaze campaign of the war. Beginning on January 4, many of the several hundred aircraft the Japanese had been saving up on Luzon were sent out on one-way missions against Allied ships.

Almost at the outset, the USS Ommaney Bay, an escort carrier accompanying the invasion fleet, was sunk when a kamikaze crashed into her and set off a series of gasoline explosions that the crew could not overcome. On January 5, kamikaze aircraft severely damaged another escort carrier, two cruisers, and a destroyer.

And on January 6, the most intense day of kamikaze attacks, 15 vessels were damaged, and the battleship New Mexico was struck by a kamikaze that killed the captain and 29 crewmen, but fortunately spared the headquarters personnel assigned to oversee Marine aviation operations on Luzon.

The three-day kamikaze effort thoroughly overwhelmed the small fighter squadrons embarked in the escort carriers and the land-based V Fighter Command units in the area, including MAG-12 and VMO-251.

In fact, the only Japanese airplanes to fall to Marine guns during the three-day kamikaze assault were credited to MAG-12 F4U pilots on January 6—a twin-engine fighter downed over Manila Bay at 3:35 pm by a VMF-211 pilot, and a Zero fighter downed over the Sulu Sea at 5:15 by a pair of VMF-218 pilots. Indeed, the latter was the last Japanese airplane downed by Marine fighter pilots in the Philippines.

As a result of the overwhelming attacks in the Philippines, General Douglas MacArthur ordered the entire U.S. Third Fleet to abort its interdiction strikes against Formosa in favor of sailing south to lend its overwhelming weight in fighters to destroying Japanese air power on Luzon. And that is what occurred.

On January 5 and 6, the fast-carrier fighter pilots downed nearly 80 Japanese airplanes in the northern Philippines, while Army Air Forces pilots downed none and Marines downed the two mentioned earlier. This, along with the suicidal tendencies of the Japanese pilots on January 4, 5, and 6, virtually eliminated Japanese air power—including kamikazes—as a factor in the Luzon invasion scenario.

The U.S. Sixth Army mounted its invasion at Lingayen Gulf on January 9, 1945, one day short of three years and a month after the Japanese mounted their invasion of Luzon over the very same beaches. The landings were virtually unopposed on land and from the air.

Marines landed at Lingayen Gulf the next day, January 10—three of them: Colonel Clayton Jerome, the MAG-32 commander and senior Marine aviator assigned to the Luzon operation; Lt. Col. Keith McCutcheon, the MAG-24 operations officer; and Colonel Jerome’s driver. Their immediate job was to locate an airstrip at which MAG-24 could set up housekeeping and begin operating as soon as possible.

At first, it looked like the Marines were going to be shut out of an early role in the Luzon campaign. It was up to Colonel Jerome to locate a suitable airfield, but he was beaten at the outset by quick-acting Army Air Forces units, which took up residence at the only strip in the beachhead as soon as it was captured. Unbelievably, in an invasion as complex as MacArthur’s return to Luzon, there had been no forward planning with respect to which aviation units would be based where.

At length, Jerome and McCutcheon located a site for a new airfield 15 miles east of the invasion beach, but preliminary engineering work proved that the ground was unsuitable, so the Marines again went looking for a place to land their planes. They ended up in a rice paddy near the village of Mangaladan, and that is where Army engineers built an airstrip by leveling nearby hills and filling the rice paddy to a height of 12 inches above the standing water.

In very short order, a 6,500-foot east-west runway was under way, and Colonel Jerome ordered Colonel Lyle Meyer, MAG-24’s commanding officer, to land with the ground echelons of both air groups. While waiting for the Army engineers to make progress at Mangaladan, Meyer and his Marines helped unload and lay steel matting at the Army Air Forces Lingayan airfield. Then the Marines went to work constructing a camp for themselves near Mangaladan.

While MAG-12 and MAG-14 F4Us continued to support U.S. Army operations in the central Philippines, the Mangaladan runway was completed during the third week of January, and finishing touches were immediately applied by Marine ground personnel. Meanwhile, Colonel Jerome was designated base commander and commander, Marine Air Groups, Dagupan (named for another nearby village). The first MAG-24 and MAG-32 SBDs arrived at Mangaladan on January 25.

Within a week, seven SBD squadrons (VMSB-133, VMSB-142, VMSB-236, VMSB-241, VMSB-243, VMSB-244, and VMSB-341) would have a total of 172 Dauntlesses based at Mangaladan; nearly 3,500 Marines would be housed at the new complex. Unfortunately, within a very short time, approximately 250 Army Air Forces aircraft also descended on Mangaladan, and all were added to Colonel Jerome’s responsibilities in his capacity as base commander

The seven MAG-24 and MAG-32 SBD squadrons were on Luzon to provide close air support for the U.S. Sixth Army. There was no other reason for them to be there. They had worked hard to provide a service no other force in the Pacific could claim as its own—direct, on-call close air support of ground troops engaged with the enemy. It was a service that only Marines would provide, and only the U.S. Sixth Army had it at its disposal. But it nearly came to nothing.

Direct air support had been used with great success throughout the Pacific War, and was being used with great success in Europe. But direct air support is not the same as close air support. For the former, virtually any type of airplane flying at virtually any altitude strikes at the flank and rear of enemy forces engaged in ground combat, or directly at enemy forces who are still some distance from friendly troops.

Direct air support includes interdiction of lines of supply and communication in proximity of the battlefield; or attacks upon supply, munitions, and fuel dumps near the battlefield; or of strikes against defended locations that are to be––but have not yet been––directly attacked by the ground forces the aircraft are supporting.

In short, direct air support is done at a distance from friendly troops, and in World War II it was usually (but not always) based on mission instructions issued before the airplanes took off.

Close air support is the technique by which airplanes operating at low altitude attack ground targets in close or even very close proximity to friendly ground troops, who are usually engaged with the enemy at the time the air attacks take place. Close air support is characterized by the feeding of instructions to the pilots by observers on the ground, within sight of the targets.

The key to close air support is direct communication between an observer or controller on the ground and the man in the cockpit. Preferably, the observer is a trained pilot assigned to the ground force by the supporting aviation force, but it could just as well be anyone equipped with an air-ground radio who, one hopes, is capable of precisely guiding a speeding airplane against a nearby ground target.

The essence of the ground-controlled close air support envisioned by Lt. Col. Keith McCutcheon, the MAG-24 operations officer who refined it, was communications between Marine aviators on the ground and Marine aviators in the air.

For this, McCutcheon invented the air liaison party (ALP), which was equipped with a jeep fitted out to allow the ALP to act much as an artillery forward-observer team acts on the ground. Ideally basing its instructions on direct observation by team members (but also capable of relaying information from other observers on the ground), the ALP would be able to coach Marine pilots against targets the pilots might not have been able to attack or even locate on their own.

If necessary, the ALP could leave the jeep to report from off-trail locations, or transceivers could be used between a member of the ALP, the radio jeep, and the aircraft. It was a flexible system, given the technology available at the time.

Another key to success was the fact that a specially trained Marine aviator was a member of each ALP jeep team; he would know what the aircraft assigned to his mission could accomplish and might even know the capabilities of individual pilots. Moreover, the MAG-24 and MAG-32 dive bomber pilots responsible for delivering ordnance had been trained to strike targets from relatively low altitudes. And they had trained long and hard to do so under the guidance of their ground coaches, which was itself a major departure from any previous norm.

It all seemed to work well in testing and training. Everyone involved was highly confident of the potential results once it was time to leave for the Philippines.

The problem was that Sixth Army senior commanders did not share the confidence Marines had in their newly evolved system. It had been tried before, albeit on an ad hoc basis, and the results had often been as deadly to friendly troops as to enemy troops. In short, the customers were afraid to use the product for, in their experience, very good reasons.

The first SBD missions flown from Mangaladan—on January 27, 1945—were support missions, but the targets were far from the fighting fronts. By the end of the month, Marine SBDs had flown 255 effective combat sorties and dispensed 104 tons of bombs, but they had yet to operate in close proximity to friendly troops or in conjunction with their ALPs.

Then there was a break. The mechanized-motorized 1st Cavalry Division came ashore on Luzon on January 27, the day the Marine aviators at Mangaladan went to work. On January 31, the crack, veteran division was inspected by General Douglas MacArthur, who gave it a unique, important assignment—a drive directly to the city of Manila.

By January 31, the U.S. Sixth Army was in some places as close as 60 miles to the Philippine capital, but Japanese resistance was stiffening in that quadrant. It was the 1st Cavalry Division’s job to literally cut through the resistance and drive into the city—exactly as Army armored divisions in Europe had cut through German defenses in France and Belgium during the previous summer’s stunning advances in that theater.

It was a symbolic move to be sure, but it had strategic overtones, for a successful drive on Manila would bifurcate the Japanese Army in central Luzon, making it easier for American forces to dominate and defeat it.

MacArthur threw everything into the 1st Cavalry Division’s drive on Manila, and that included his promising but untried weapon, Marine close-air support. The cavalry would have to drive 100 miles to the city from its line of departure, and it was to have Marine dive bombers overhead and on call every yard of the way.

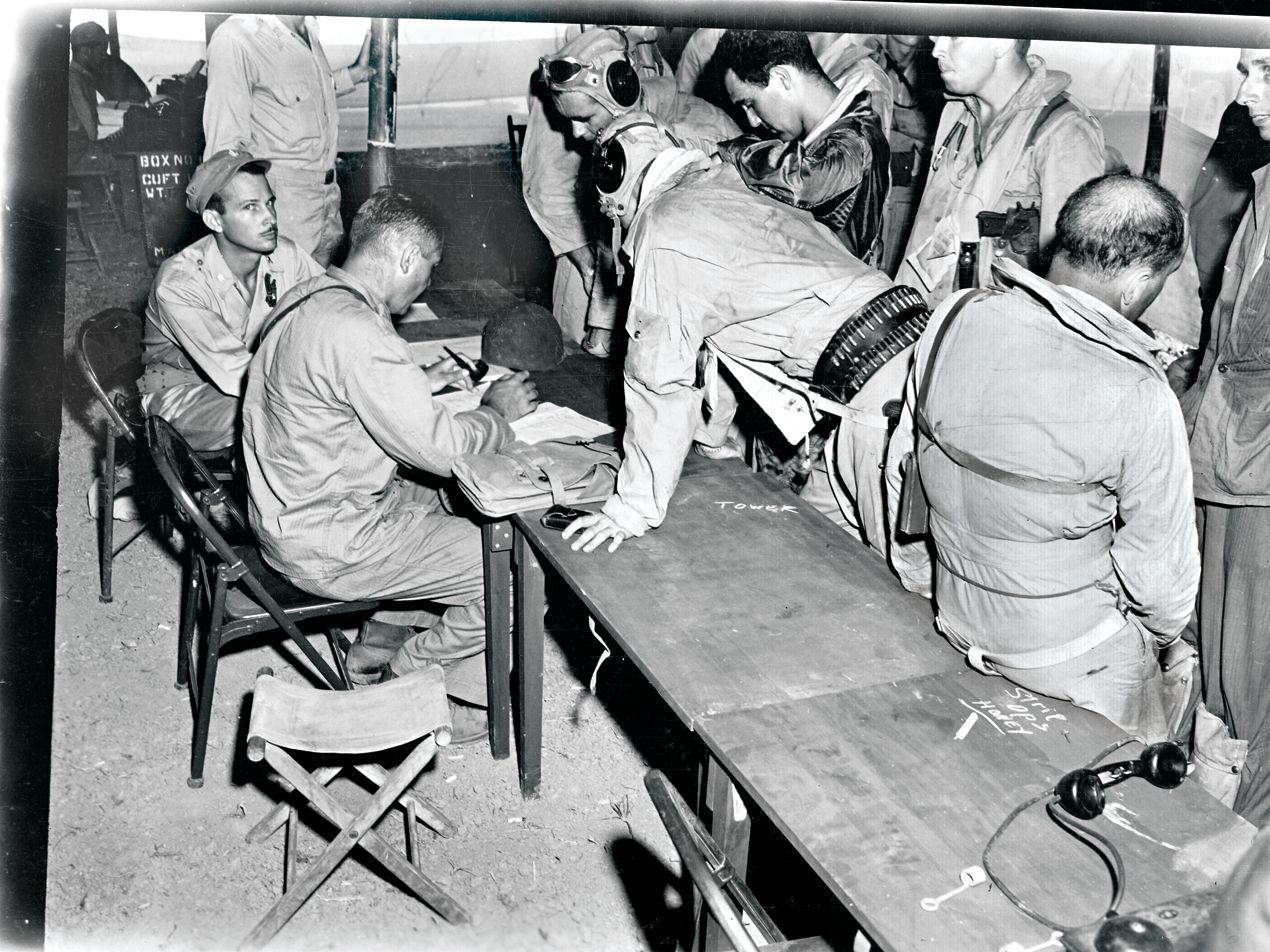

The 1st Cav’s operational plan for air dovetailed beautifully with Marine Air’s capabilities. Under the usual regime, mission directives were issued the night before by the 308th Bombardment Wing, the V Bomber Command sub-headquarters in charge of all the Allied bombers operating over Luzon. But the 1st Cav had organized what it called a “flying column,” which would take ground as it could, as much as possible for as long as possible. The flying column commander, Brig. Gen. William Chase, felt that rigid mission orders would be to his disadvantage; he wanted his air support overhead and on call, to use as and when he needed it.

General Chase’s concept was a perfect match for Marine training and organization. The ALPs were mobile; they could operate with the mechanized flying column without any problem. And, of course, they were trained and equipped to direct all manner of aircraft as and when needed. And the Marine SBD crews had been trained to attack close-in targets while being guided in real time by observers on the ground, with the forward-most ground troops. The Marines could provide dawn-to-dusk air cover, however the cavalry needed it.

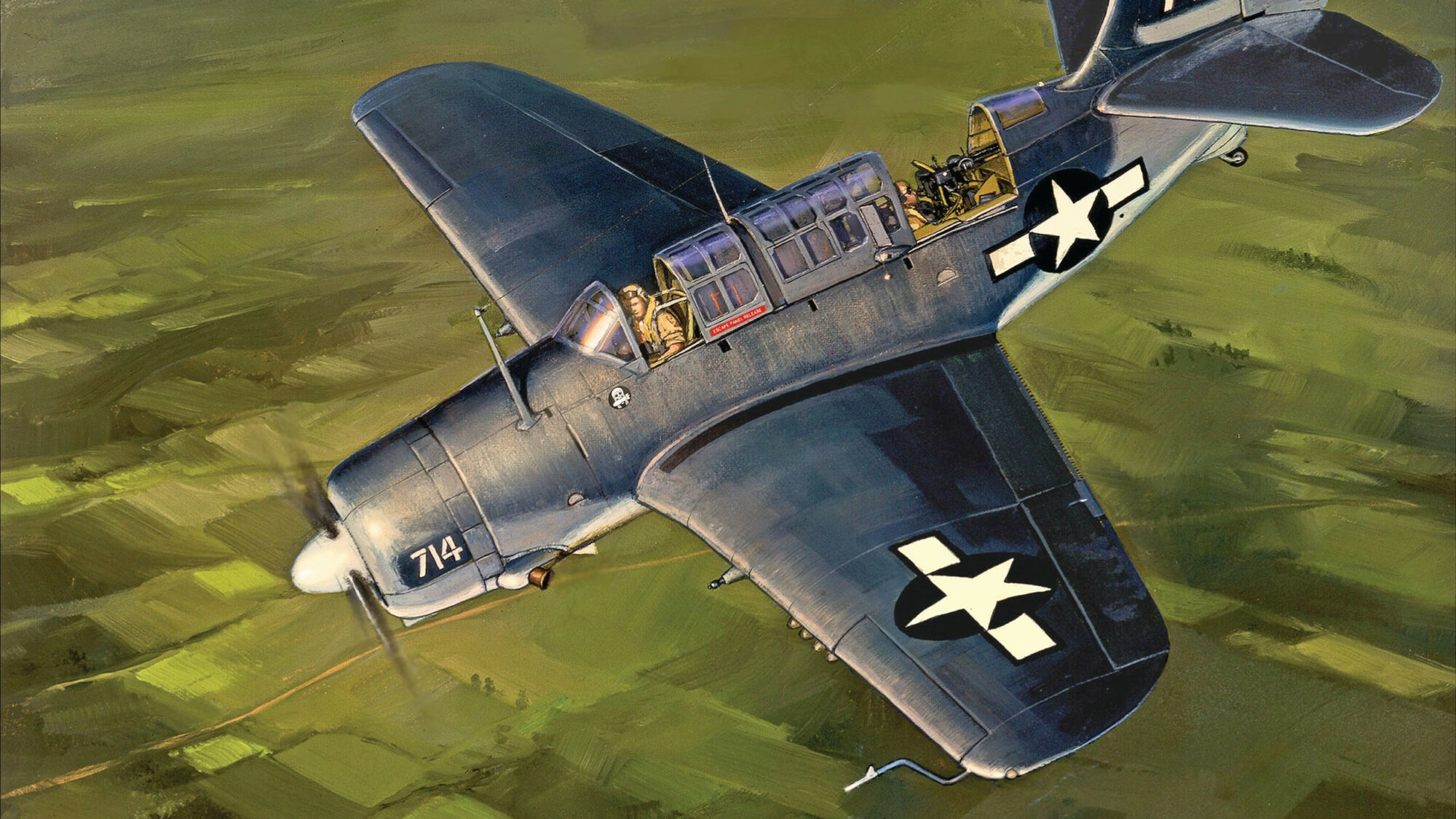

This long after World War II, few people realize what a precision bombing instrument the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps had in the Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bomber. An examination of the SBD’s use will reveal that it was simply the most effective aerial weapon the United States produced for an antishipping role. The SBD was a precision weapon.

It carried one large bomb, and it was designed to use that bomb to strike lithe, fast-moving ships at sea that could do much to throw off the aim of even skilled and determined pilots. And yet, of all the aircraft types the United States used against Japanese ships at sea throughout World War II, the SBD was, bomb for bomb, by far the most effective. It was, for example, the only type known to have struck fast Japanese aircraft carriers at Midway; SBDs sank four carriers in one day there.

The SBD was so maneuverable that it often went up against Japanese fighters if it had to defend itself, and early in the war SBD pilots had scored enough aerial victories against Japanese fighters to be worthy of comment. That maneuverability, of course, was designed so that an SBD diving at a 60-degree angle at several hundred miles per hour against a narrow, writhing ship was responsive enough in the hands of its pilot to hit that ship. And hit ships the SBDs had done—early in the war, when it really counted, when there were few SBDs and far too many Japanese ships.

There were no SBDs at sea aboard American carriers in early 1945; the only service that still had any in combat was the Marine Corps. It was an old weapons system, but it was still effective, for there was nothing that was not known about the venerable SBD’s combat performance characteristics, even by the greenest of Marine SBD pilots.

If the SBD could hit the narrow, dodging decks of speeding ships at sea, there was nothing it could not do to destroy fixed land defenses or troop or supply columns on the roads and paths of central Luzon.

The ALP assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division for the drive on Manila consisted of a radio truck and two jeeps. Each jeep was manned at all times by a Marine pilot assigned to ground duty and an enlisted driver. Teams from MAG-24 and MAG-32 shared the responsibility. The MAG-24 communications officer and at least two other Marines manned the radio truck.

When the first jeep reported for duty, General Chase, the 1st Brigade commander, told the occupants to stay with him at all times. And so, just like that, Marine Air became the commanding general’s weapon of opportunity. The second jeep was assigned to the 1st Cav’s 2nd Brigade, where it was also taken in tow by that unit’s commanding general. The radio truck was consigned to the Cav Division command post and made part of the division commander’s entourage.

The plan was to have nine SBDs overhead at all times, ready to pounce as and when needed. The pilots simply circled over the cav column in large, lazy circles, conserving fuel and watching events unfold on the ground. As a practical matter, the orbiting SBD crews were able to search and observe an area approximately 30 miles ahead and 20 miles to either side of the flying column’s route of advance.

The cav’s first task was to capture its own line of departure, the town of Cabanatuan, which was on Route 5, the main central road to Manila. The attack commenced on February 1 and took all day to achieve its objective. During the day, 18 Marine SBDs expended their bombs on targets designated by the Marine aviators assigned to General Chase’s ALP. The targets were troop concentrations and enemy defensive zones. As far as is known, all bombs struck the intended targets.

During the morning of February 2, ground-directed SBDs attacked Japanese positions just ahead of the advancing cav vanguard, which drove more than halfway to Manila before noon. Farther along, in fact, the cav flying column linked up with a vanguard element of the 37th Infantry Division, which was advancing on Manila by another route.

Shortly after the link-up, the cav ran into determined opposition that could not be overcome. The Japanese were on dominant high ground, and the cav troopers could not budge them. The lines were intermingled; there was no room to plant bombs on the enemy position without endangering friendly troops. So, under direction from the ground teams, MAG-32 SBDs mounted several strafing passes against the stoutly emplaced defenders, but they did not fire a shot.

The Japanese could not be sure what the SBDs might do, even by the last dummy firing pass, so they ducked every time an airplane buzzed their stronghold. And by ducking, they allowed the cav troopers to win through. The position was taken with the aid of Marine Air even though the Marines didn’t expend a single bomb or bullet. All that low-level attack training paid off. By the end of the day on February 2, the cav vanguard was just 15 miles from downtown Manila.

On February 3, Marine Air’s most important contribution to the drive on Manila came simply from being there. Orbiting SBDs waiting for combat assignments reported that a vital bridge right behind the battlefront was still standing. The cav troopers massed before the critical point and drove a wedge to the bridge, which was captured just before an explosive charge would have dropped it into the river. The result was that the cav’s wheeled and tracked vehicles had a dry, easy crossing.

And so the cav vanguard was able to cross into the Manila city limits by 6:35 that evening. Indeed, the cav troopers kept going as dusk descended, and they did not stop until they had liberated 3,700 maltreated civilian internees from their prison camp at Santo Tomas University.

The cav’s 100-mile dash was completed in 66 hours. The battle for Manila would take exactly a month, until March 3, to reach its inevitable conclusion, and by then Marine Air was off doing many other jobs. But those 66 hours over the cav were critical to the success of the mission the Marines had come to Luzon to undertake.

The SBD pilots and the MAG-24 and MAG-32 ALPs won the respect of their prospective clients. Thereafter, Army ground commanders accepted Marine Air support when it was offered, and indeed they often vied with one another to get it assigned.

The initial use of Marine F4U Corsairs on the island of Mindanao was undoubtedly the strangest use of Marine airmen to be made in World War II. This was because the Corsairs, their pilots, and a small contingent of ground personnel preceded the American invasion of the island by several weeks. Marine Air preceded American ground forces to an enemy-held island!

It had been planned all along that Marine Air would take part in the liberation of the southern Philippines. Two Marine fighter groups had taken part in the liberation of Leyte, in the central Philippines, and two Marine dive bomber groups were actively and fruitfully engaged in supporting U.S. Army ground forces on Luzon, in the northern Philippines. The grand plan for the invasion and liberation of Mindanao and other islands in the south included a prominent role for both Marine fighters and dive bombers in a ground-support role.

But Marine Air—in the form of several Marine Air Group 12 Corsairs—arrived in the southern Philippines ahead of any other invasion force.

Between the time Mindanao was surrendered to the Japanese invaders in mid-1942 and the arrival of two Corsairs on March 7, 1945, an American-led guerrilla force composed mainly of Filipino fighters had been able to take largely uncontested control of several areas on the huge island.

Among these was the Dipolog area, in the northern part of Mindanao’s isolated, hook-shaped Zamboanga Peninsula. There, in 1943, the guerrillas had built a small airstrip for the use of supply aircraft bringing in needed war materiel. The facilities at Dipolog Airstrip were rudimentary but certainly adequate to the task for which they were intended.

The Allied plan was to land a reinforced U.S. Army infantry division on March 10, 1945, at Zamboanga Town, at the southwestern tip of the Zamboanga Peninsula, about 150 miles from Dipolog. By then, many of the lightly held islands in the central Philippines would have been liberated, and the huge Japanese garrison on the main island to the north—Luzon—would have been defeated or dispersed. In fact, the outlook for Luzon was so sanguine that nearly the entire complement of Marine aviation units in use in the northern and central areas was slated to be moved south to support the Mindanao operation.

Dipolog became important to American planners when it was learned that an airfield under way on Palawan Island could not be completed in time to support air operations required to cover the southern Zamboanga invasion. Since by that stage of the Pacific War air support was deemed essential to the success of any amphibious invasion, the planners, in casting about for a solution, decided to take control of Dipolog as an advance fighter base. The guerrilla airstrip, which was a going concern, could be placed in use in time to meet the requirements of the Zamboanga invasion force.

On March 2, in a move that does not seem to have been approved through channels by senior headquarters, two officers and six enlisted Marines from Marine Air Group 12—an all-Corsair command—arrived at Dipolog by air transport. Their mission was to assess the needs of the guerrilla forces in the region who would protect the base and to do what they could to ready the field for the arrival of the first MAG-12 Corsairs.

Two Corsairs landed at Dipolog on March 7. Once again, it is not clear if higher headquarters had a hand in authorizing the expedition, for it was not until the next day that two heavily reinforced infantry companies of the Eighth U.S. Army’s 24th Infantry Division were “rushed” to Dipolog by air to further secure the guerrilla-held airstrip. More MAG-12 Corsairs also reached Dipolog on March 8, and by the day after that 16 Corsairs were operating from the field, flying their first sorties in support of Filipino guerrilla forces engaged in setting the stage for the imminent invasion.

Those initial sorties were a bit strange in the varied experience of Marine Air in the Pacific War. Two of the MAG-12 Corsairs on an armed reconnaissance sweep flew over a large force of armed men who were attired in civilian dress. The armed men were near the coast, and on a nearby beach were four small craft that appeared to be filled with supplies. When the Corsair pilots flew lower for a better look, the armed men all waved. Moreover, an American flag was shown. Believing the force to be composed of Filipino guerrillas, the Corsairs returned to Dipolog—where guerrilla liaison officers averred that the Corsair pilots had located a force of Japanese soldiers dressed as Filipino guerrillas. The same two Corsairs returned to the scene and strafed the armed men and the four supply craft, but most of the men on the ground escaped into the thick forest.

The real invasion of Mindanao took place without incident near Zamboanga Town, 150 miles from Dipolog. Following a preinvasion air bombardment by the U.S. Thirteenth Air Force that began in earnest on March 1, the 41st Infantry Division came ashore under heavy naval and air cover against negligible opposition. Zamboanga Town was captured during the afternoon, but resistance stiffened before the Army troops could take San Roque Airfield, which was slated for use by aircraft from MAG-12 and MAG-32 (F4U Corsairs and SBD Dauntlesses, respectively).

Despite the heavy resistance at the front and the attendant delay in taking San Roque, headquarters and ground personnel from the two Marine air groups began landing late on March 10. As soon as San Roque was declared secure on March 13, an Army aviation engineer battalion moved in to improve the base. So did Colonel Clayton Jerome, the MAG-32 commander, who would be overseeing all the Marine Air units in the region under the designation commanding officer, Marine Air Groups, Zamboanga (MAGsZAM). As soon as the newly liberated airfield was turned over to his care, Jerome formally renamed it Moret Field in honor of Lt. Col. Paul Moret, an early Pacific air warrior who had died in a plane crash in 1943.

It would be a few days before Moret Field would be operational, so the burden of providing near-in air support to the 41st Infantry Division fell upon the small contingent of MAG-12 Corsairs at Dipolog. From the outset, as intended, the Marine airmen conducted close and direct support of the Army troops expanding their Zamboanga perimeter.

Though the Philippines had been scoured pretty clean of Japanese air power since the initial landings at Leyte in September 1944, there were still several Japanese aircraft based on Mindanao (of an original complement of 1,200). The only one of them to appear during the initial invasion phase was a fighter that made two strafing passes and dropped one small bomb against Moret Field on March 13. Despite the presence of Thirteenth Air Force fighters, the Japanese airplane escaped.

As soon as Moret Field was declared operational on March 15, eight VMF-115 Corsairs set down there. Three days later, all the Corsairs from VMF-211, VMF-218, and VMF-313 arrived, as did an Army Air Forces North American P-61 Black Widow night fighter squadron.

The first Marine close-support mission undertaken from Moret Field was on March 17. The MAG-32 intelligence officer was on the ground with one of the regiments of the 41st Infantry Division, and he called the initial support missions after obtaining permission from the division commanding general. (Some senior Army officers did not want airplanes dropping bombs and spraying bullets anywhere near their troops, others had to be convinced, and a few had an instinctive grasp about what the aircraft could accomplish. Maj. Gen. Jens Doe, the 41st Infantry Division’s veteran commanding general, was one of the latter. If he had not been, MAGsZAM would have been a wasted effort.)

The first few ground-support missions harkened back to the first few combat missions undertaken by Marine Air at Guadalcanal in August 1942. When the first MAGsZAM Corsairs began operating from Moret Field, the base was still within sight of the front lines on which 41st Division troops were battling determined Japanese ground forces.

While that was going on, if the mission were not an emergency, the flight leader typically visited with the Marine air liaison party that would be guiding his flight during the actual attack. A good look at the objective from the ground usually had a positive effect on the accuracy of the mission. This method soon became unwieldy and finally impossible to continue, but it was fine while it lasted, and it certainly put Marine aviators in the right frame of mind for future ground-support missions.

On March 18, eight Corsairs each dropped a 1,000-pound bomb on Japanese troops dug in near Zamboanga Town, and then the Marine pilots strafed the zone and a large area around it. Later, eight other Corsairs dropped napalm on a defensive zone atop a ridge, also near Zamboanga Town. The 41st Division troops facing these enemy positions, which were obliterated, were thankful, because if it had not been for the Corsairs they would have had to clear the defenses the old-fashioned way.

On March 21, a Marine air liaison party installed a radio in an Army L-4 spotter plane and relayed directions from the air via the team’s jeep-mounted radio. The importance of this innovation was that the aerial spotters could see in relatively slow motion what Corsair pilots had to find and attack at much faster speeds. The result was a greater degree of accuracy and a major step toward techniques that are today taken for granted. Moreover, following the first such mission the Japanese withdrew from the target area after blowing up two of their own On March 21, a Marine air liaison party installed a radio in an Army L-4 spotter plane and relayed directions from the air via the team’s jeep-mounted radio. The importance of this innovation was that the aerial spotters could see in relatively slow motion what Corsair pilots had to find and attack at much faster speeds. The result was a greater degree of accuracy and a major step toward techniques that are today taken for granted. Moreover, following the first such mission the Japanese withdrew from the target area after blowing up two of their own ammunition dumps.

A mission on March 22 involved 16 Corsairs, each armed with a 500-pound bomb. The target was a network of well-constructed pillboxes on an L-shaped ridge. Guided by an air liaison party on the ground, 13 Corsairs dropped their bombs with such accuracy that the follow-on ground assault by an infantry battalion was unopposed, and 63 Japanese corpses had been located in the bomb zone by nightfall.

The first Marine dive bombers reached Moret Field on March 24. Only a day earlier, Marine aviation units had been released from the Luzon operation, which was winding down. The first SBDs to arrive at Moret Field were several flights from VMSB-142 and VMSB-236, which were by then specialists in the art of providing pinpoint, on-call close air support for ground troops engaged in jungle combat. The arrival of the dive bombers added a whole new dimension to the Marine Air effort in Zamboanga.

On March 27, several hundred Japanese ground troops were located as they marched against Dipolog Airstrip in northern Zamboanga. Several MAG-12 Corsairs were still operating from the guerrilla base, and Army and Marine ground crewmen were in residence.

Taking into account the utter lack of combat experience among the approximately 500 Filipino guerrillas holding Dipolog, MAGsZAM headquarters ordered all aviation personnel and the Corsairs to evacuate the place as the Japanese force drew nearer. This was done by the afternoon, but Major Donald Willis, the U.S. Army officer commanding the guerrillas, prevailed upon his Marine compatriots to at least attack the Japanese once before they arrived at Dipolog.

Four Corsairs were dispatched from Moret Field, and they landed at Dipolog to receive a final briefing from Major Willis, who suggested that the attack might be more profitable if he went along as an observer. The flight leader agreed, and Willis squeezed into a Corsair cockpit with the smallest of the Marine pilots on his lap. It worked. With Willis directing the Corsair division, the Marines used up all their ammunition in six devastating strafing passes against the Japanese force, and the Japanese withdrew.

Also, while the flight leader received a royal dressing down from his superiors, Major Willis was awarded a Silver Star by his. But the job got done, and Dipolog was not attacked.

On March 30, MAGsZAM was reinforced by the flight echelon of VMB-611, the first and only Marine PBJ (B-25 Mitchell medium bomber) unit to take part in the Philippines campaign. And the VMB-611 PBJs were not ordinary twin-engine medium bombers, either. The 16 medium bombers were specially rigged as powerful ground-support gunships capable of being armed with between eight and 14 heavy machine guns, eight aerial rockets, or 3,000 pounds of bombs. And each PBJ was equipped with its own radar-guidance system, designed to assist in pinpoint night attacks against ground targets.

They could also undertake photographic reconnaissance missions, day or night, and the crews had even tried their hands at dive bombing. Also unlike standard PBJ medium bombers, the VMSB-611 aircraft were manned by two-man crews, the pilot and co-pilot. And the unit had undergone rigorous special training. There were several U.S. Army Air Forces units equipped and trained for similar missions, but VMB-611 was unique in the Marine Corps.

The attachment of VMB-611 made MAGsZAM a 24-hour-a-day concern. The PBJ squadron’s first operational missions were antisubmarine patrols and long-range reconnaissance missions to Borneo and the sites of several proposed future landings in the Sulu Archipelago. None of these missions allowed the unit to show its unique combat capabilities or fighting spirit, but they were necessary. Moreover, VMB-611 was the only MAGsZAM unit with the range and training to undertake these missions.

While examining landing sites in the Sulus, the PBJ pilots attacked truck convoys, airfields, and such other targets as happened to pass in front of their gunsights. They also undertook scheduled night heckling missions against enemy airfields (though the bases had been pretty much abandoned by that point in the war).

Even as the 41st Infantry Division spread slowly across Mindanao under an aerial umbrella provided mainly by MAGsZAM, the Eighth U.S. Army’s 40th Infantry Division mounted an unopposed invasion of Panay, in the Visayan Islands north of Mindanao, on March 18. The bulk of the air cover for the landings and subsequent reconquest of the islands was provided by three MAG-14 Corsair squadrons based to the north on Samar.

There was not much to do. The Japanese had withdrawn all but a few of their fighters from Panay, and resistance on the ground was light. Indeed, the island was defended by about 1,500 Japanese troops, who took to the hills and waged a guerrilla-style campaign until the Pacific War ended in August 1945.

Marine Air was also on hand when the Americal Infantry Division invaded Cebu on March 26. There was little opposition, but the beach was extensively mined—not the sort of defensive effort that could be countered from the air. There was considerable opposition as the U.S. Army troops advanced on Cebu City later in the day, and here the three Samar-based Corsair squadrons of MAG-14—VMF-222, VMF-223, and newly redesignated VMF-251—played a vital role when they strafed ground defenses and a motor column carrying reinforcements.

Following this relatively large battle, the Japanese defenders withdrew into the interior to wage a guerrilla-style campaign. MAG-14 provided support against dug-in defenders when it was required, but the requirement was hardly taxing.

Once again supported by MAG-14 Corsairs, elements of the 40th Infantry Division invaded Negros on March 28, 1945. This landing was unopposed, and the American ground troops, aided as needed by Marine Corsairs, were again drawn into a protracted guerrilla-style campaign.

By early May, the need for air support in the Visayan Islands had diminished to the point where it was decided that MAG-14 could be employed more profitably elsewhere in the Pacific. The group was ordered to stand down and prepare to be transferred to Okinawa, and combat operations ceased on May 15.

MAGsZAM’s role expanded on April 2, 194, when elements of the 41st Infantry Division landed at Sanga Sanga Island, 200 miles from Mindanao, at the southern extremity of the Sulu Archipelago and only 30 miles from Borneo in the East Indies.

Guided by a MAG-12 air-support command team aboard a U.S. Navy destroyer, VMF-115 and VMF-313 Corsairs supported the invasion against light opposition and provided a protective umbrella for the invasion flotilla. By the end of the day, MAG-12 had a jeep-mounted air liaison party ashore that guided VMF-115 and VMF-211 Corsairs in strafing attacks against several ground targets, including a radio station.

The day’s second landing, on Bongao Island adjacent to Sanga Sanga, included a preinvasion strike by 44 MAG-32 SBDs, which dropped a total of 20 tons of bombs on preselected targets, and called strikes by VMSB-236 SBDs against a Japanese observation post and troop concentrations. Thereafter, until April 8 when no more profitable targets could be found, MAG-12 Corsairs were on station over Sanga Sanga and Bongao during daylight hours.

On April 4, MAGsZAM SBDs mounted their first attack against Jolo, an island in the Sulu Archipelago that had been bypassed by the Sanga Sanga and Bongao invasion force on April 2. There were relatively few Japanese on Jolo, and they were dominated by an even larger force of Filipino guerrillas.

The uncontested preinvasion aerial bombardment by MAGsZAM aircraft continued until April 9, when elements of the 41st Infantry Division sailed 80 miles from Zamboanga and invaded the place. Shortly after the beachhead was secured, a 16-man jeep-borne Marine air-ground liaison team came ashore and began calling strikes. Jolo was lightly defended, but it was large and heavily wooded, so progress on the ground was slow even if it was not particularly bloody.

Given that Moret Field was only 80 miles from the battle area and that MAGsZAM assets were vastly underutilized in other operations, the Marine Corsairs and Dauntlesses were called upon to strip away heavy cover ahead of American ground troops and Filipino guerrillas through the liberal use of napalm.

The strongest opposition the Japanese put up on Jolo was the defense of Mount Daho by about 400 well-armed rikusentai (special naval landing troops). Preceding the April 16 ground attack was a severe bombardment by artillery and Marine fighter bombers and dive bombers against specific Japanese strongpoints. Despite the strength of the bombardment, the ground attack failed at the outset.

On April 18, MAGsZAM put up an all-out effort: 45 SBDs from VMSB-243 and VMSB-341 attacked the stout defenses with 21 tons of bombs. And the next day, 65 VMSB-236 and VMSB-243 SBDs did the same. It was later determined that 35 of 42 bombs dropped on one particular defensive area on April 19 were direct hits.

The ground attack against Mount Daho resumed on April 20, but it once again bogged down in the face of determined opposition. Next day, between artillery barrages, 70 MAGsZAM SBDs dropped 15 tons of bombs on the defenders. And on the morning of April 22, 33 SBDs and four rocket-firing VMB-611 PBJs attacked just prior to a renewed ground offensive.

Thanks in large part to Marine Air (and incessant artillery strikes), the American and Filipino ground troops finally overran the objective, where more than 235 Japanese bodies were recovered from bomb- and artillery-damaged caves, bunkers, and pillboxes. Even so, fighting on Jolo continued nearly to the end of the war as the Japanese survivors went over to a guerrilla-style defensive campaign in which American air support played a minor role.

For Marine Air, the conquest or neutralization of Japanese garrisons on the Zamboanga Peninsula and in the Visayan and Sulu Islands in March and April 1945 left just one major objective in the southern Philippines: the reconquest of the major portion of vast Mindanao, with its 35,000-plus Japanese defenders. For practical purposes, the reconquest of Mindanao’s Zamboanga Peninsula and the main portion of Mindanao were entirely separate operations owing to the mutual isolation of the regions by ranges of impenetrable mountains.

The preliminary work against Mindanao (as distinct from the Zamboanga Peninsula) began shortly after MAGsZAM units started operating from Moret Field. Working in support of a very large and effectively organized 25,000-strong Filipino guerrilla army, Marine aircraft attacked numerous objectives around the island.

In early April, the main thrust of the attention shifted to the Malabang area, directly opposite the Zamboanga Peninsula. There, the American-led guerrillas worked toward ejecting the Japanese garrison in advance of the projected April 17 landing by the two infantry divisions comprising the Eighth Army’s X Corps. Indeed, with the help of Marine Air, the guerrillas forced the Japanese to abandon Malabang on April 5.

On the same day the Japanese withdrew from Malabang, Marine Corsairs began operating from a guerrilla-held dirt airstrip there. Here, as at Zamboanga’s Dipolog airstrip in early March, crude facilities allowed for the deployment of only a few aircraft at a time.

And as at Moret Field shortly after its occupation by Marine Corsairs, the front line was within sight of the runway. Marine pilots about to take off in support of the guerrilla forces often had an opportunity to directly view their objectives from the airstrip.

Often as not, the flight leaders were driven to frontline observation posts manned by Marine air-ground liaison teams. And in some cases, bombs were released on targets within 800 yards of the end of the runway. It was an exciting time for the Corsair pilots who took part, and virtually unique in the annals of Marine Corps aviation, for the actual invasion of the area by American ground forces had not begun.

In the six days leading up to the April 17 invasion, MAGsZAM Dauntlesses and Corsairs based at Moret Field joined in the general preinvasion bombardments by Army Air Forces bombers and U.S. Navy surface warships. Here, as they always did in the Philippines—and as they had in the Solomons––the Marines fully integrated themselves into an effective multi-service effort.

By April 11, pressure from the guerrillas and air and naval bombardment forced the Japanese to withdraw from Parang, the second initial objective of the X Corps invasion force. And by April 13, the Japanese had been driven far enough back from both Malabang and Parang to ensure an unopposed landing. By then, the Malabang airstrip was well beyond sight of the frontline action supported by its contingent of Marine Corsairs.

In the end, Malabang was invaded by a single infantry battalion rather than a full division, and the main show was shifted on the run to Parang, which was 17 miles closer to other important objectives. Although 35 MAGsZAM SBDs and 30 Corsairs were placed on station over Parang and the invasion flotilla as the landing force swept ashore, the overall campaign leading up to the invasion had been so effective that the landings were utterly unopposed, and there was no aerial opposition whatsoever.

By day’s end, Marine Air Warning Squadron 3 had set up its radar and communications equipment in the beachhead area, and Marine air-ground liaison teams were operating at the forefront of the unopposed beachhead expansion.

On April 18, U.S. Army aviation engineers began expanding the dirt airstrip at Malabang for the impending arrival of an advance flight detachment of MAG-24 from Luzon. On April 20, VMSB-241 did arrive from the north, and VMSB-133 and VMSB-244 arrived on April 21 and April 22, respectively.

These moves brought all Marine aviation units left in the Philippines to Mindanao under the direct control of MAGsZAM. The newly expanded airfield at Malabang was named for Captain John Titcomb, a Marine aviator who had been killed in the front lines on Luzon while acting as head of a Marine air-ground liaison party.

As the regiments of the X Corps’ two infantry divisions increasingly diverged from west-central Mindanao, MAG-24 SBDs came to play an increasingly wide-ranging and hectic role. In addition to several Marine air-ground liaison teams, the task of calling air support missions was picked up by 12 similar teams from the Army’s 295th Joint Assault Signal Company—teams organized and equipped in large part upon the successful Marine model. Air support operations on Mindanao exactly fulfilled the vision upon which the air-ground teams had been built.

Once fearful of calling air strikes too close to their own lines, U.S. Army infantryman taking part in the Mindanao campaign often would not advance unless Marine Air and air-ground liaison teams were on hand to give them precision support at very close ranges. Once underutilized—if utilized at all—Marine air-ground support operations mounted from Titcomb Field and, to a lesser extent, Moret Field, became exhausting work.

By the middle of May, some days saw the pace reach to between 150 and 200 effective sorties, and on one memorable day, 245 Marine Corsair and Dauntless sorties resulting in the release of 155 tons of bombs against targets identified in the main by air-ground liaison teams. Long gone were the days in mid-1944 when it seemed that Marine Air had been relegated to an unimpressive role in the backwaters of the bypassed South Pacific.

On June 1, 88 Marine SBDs mounted what can be called their first saturation mission of the war upon a very small piece of real estate that could not otherwise be overcome by U.S. Army infantry and artillery. The mass attack, which included a number of napalm bombs, was spectacularly accurate—and successful. Indeed, when the American ground troops stormed the hitherto unapproachable defensive zone in the wake of the bombing attack, they were unopposed.

June 1 also saw the beginning of a new trend in the Pacific War. On Mindanao, VMF-313 was decommissioned in the field, and its aircraft and personnel were shipped home or dispersed to other units. Though there were still busy days ahead for Marine Air on Mindanao, the Philippines campaign was winding down and even the projected autumn invasion of Japan did not require the number of Marine aviation combat units then available in the Pacific.

On June 19, a 31st Infantry Division artillery spotter plane located large Japanese troop columns in an inaccessible area of Mindanao, and the job of attacking them was turned over to MAGsZAM. Every available Marine SBD was mustered for this mission, and on June 21, after thorough plotting of targets from the air, 148 Marine dive bombers took part in dropping a total of 75 tons of bombs on troop concentrations, bivouacs, supply dumps, and other targets.

Bad weather prevented an accurate accounting of the results, but large fires were observed and many bodies could be seen from the air when the weather cleared. It was later estimated that 500 Japanese died in the attack.

By June 30, thanks in large part to the tireless efforts of Marine airmen and the support of their ground crews, Mindanao was declared secure by the Eighth Army commanding general. By that date, Marine airmen had completed 10,406 effective combat sorties and dropped nearly 5,000 tons of bombs on Mindanao alone.

Thousands of Japanese remained on the island, but they were not under a central authority as they fought on through the cessation of hostilities in August. Marine Air remained on call on Mindanao until the end of the war, but there were few profitable missions flown after the middle of July.

In sum, the efforts of Marine Air in the Philippines were pivotal. In addition to bolstering the Army’s Far East Air Forces during the critical early phase of the bold jump into the central Philippines in late 1944, Marine Air undertook a specialized and ultimately integral ground-support mission that U.S. Army Air Forces units were neither equipped nor trained to accomplish.

Despite early mistrust of their techniques on the part of would-be clients, Marine airmen provided necessary and at times critical support of U.S. Army ground forces from nearly the beginning of the Philippines campaign to the very end. In selling their vision, they more than proved the value of their then unique concepts for supporting ground forces from the air.

These concepts were studied and polished while they were being put to use in the Philippines, and they served as the forerunners of air-ground cooperation techniques that exist as a matter of course to this very day. Marine Air’s undeniable contributions to the success of the Philippines campaign are all the more savory for their having been initiated as an afterthought, as a means to put hard-won, often unique combat expertise to fitting, war-winning use at a time when the entire Marine aviation enterprise was in danger of being relegated to a necessary but peripheral role.

Marine aviators serving in the Philippines more than overcame the initial skepticism of their colleagues in other services; they wrote new chapters in the handbook on war in the air, and they made their particular expertise indispensable in their war and in all American wars since.

The Jack Fellows artwork actually depicts a pair of SB2C Helldivers–the successor to the SBD Dauntless. Called “the Beast” by pilots, it was not as favorably looked on by those who flew it.

Was gonna say the same as Mr Wilson! 🙂

I had a very good friend who flew the SB2C Helldiver during WWII and never heard him say one bad thing about it. I think the negative reviews depended on the individual pilot and his experiences with the aircraft. The RAF was not too keen about the first iteration of the P-51 Mustang. The only Allied pilots who liked the Bell P-39 Aracobra were the Soviets. The Martin B-26 Marauder was called the “Widow Maker” because of the many accidents in which it was involved. I could go on and on with other examples but I think I got my point across. It just depends on the pilot so I think it is unfair to make such a broad criticism of the Curtiss Helldiver which was a vast improvement over the SBD Dauntless, even if some thought SB2C really stood for Son of a Bitch 2nd Class 😉.