By Peter Suciu

The city of London practically overflows with military history. Predating the Romans, London has been the seat of government ever since it was fortified by William the Conqueror in the 11th century. Today, visitors can see daily military parades, take in the sights of the Tower of London, and tour countless museums devoted to military history. But the best-kept military secret isthe National Army Museum in Chelsea, a site often overlooked by tourists but nevertheless a premier museum with a collection that few other institutions can come close to rivaling.

When it comes to museums, London leads the world. Even Washington, D.C., pales when compared to London. The city and its surrounding suburbs are home to more than two dozen museums, and military history buffs will find no shortage of things to do and see. The British Museum offers a look at ancient Roman, Greek, and Celtic arms and armor, while the Victoria and Albert Museum features an equally impressive collection of Asian armor. Other museums are devoted specifically to military history. Among these is the Imperial War Museum (IWM), which is without a doubt one of the world’s premier museums on the subject of military history. Its collection focuses specifically on war in the 20th century, including World Wars I and II, with a somewhat lesser look at the Cold War and other regional conflicts. Likewise, the Royal Artillery Museum, the Royal Air Force Museum, and the HMS Belfast (a branch of the IWM), are other must-see attractions.

And of course there is the Tower of London, which was first constructed during the reign of William the Conqueror and expanded over the years. The Tower was home to Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell, who opted to live there rather than in the more stately royal palaces around London. Today the Tower is among the most visited attractions in London.

Often overlooked is the National Army Museum in Chelsea. It is located adjacent to the Royal Hospital Chelsea, the home of the “Chelsea Pensioners,” which houses British soldiers unfit for duty due to injury or old age. The rather nondescript museum building—especially considering the grander looking Royal Hospital next door—is filled with objects commemorating the history of the British Army, from the time of the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 to the modern day. The museum offers a serious look at the history of the British military while still providing plenty of activities for those who never lost their childhood dream of glory and adventure.

Six Permanent Galleries

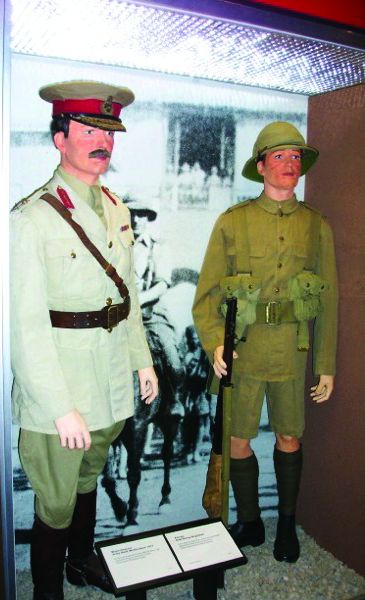

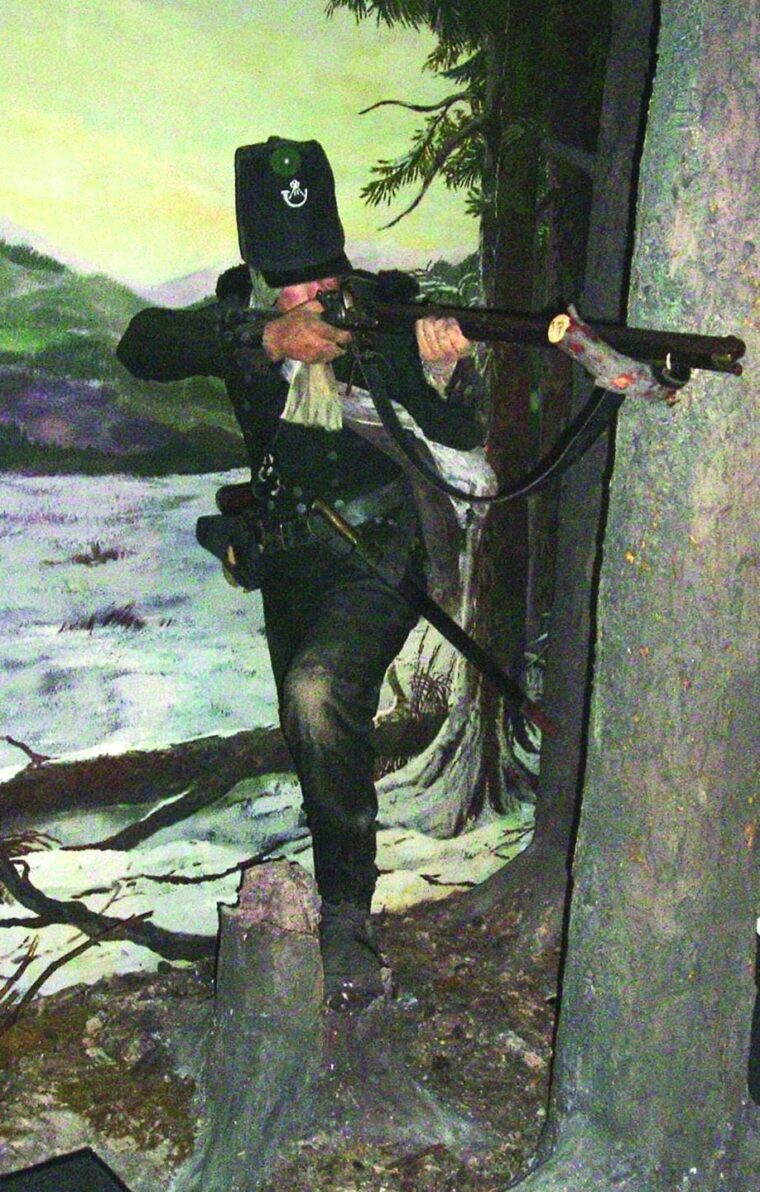

The National Army Museum is home to six permanent galleries, which are arranged chronologically and begin as might be expected with the earliest days of the English Army during the Hundred Years’ War. The gallery, known as “Redcoats: The British Soldier 1415-1792,” focuses on the early conflicts of the United Kingdom, offering insight into the regimental system, which remains unique to the British Army. This gallery looks at the evolution of the modern army and the effects of the English Civil War, while also showing the changes in the uniforms and equipment through the nearly 400-year period.

The “Changing the World” gallery, which was previously known as the “Road to Waterloo,” explores the later changes brought on by this conflict. Here, visitors can see numerous artifacts captured from Napoleon’s forces, including a French eagle standard from the 105th Infantry Regiment, which was captured by Captain A.K. Clark of the 1st Royal Dragoons.

The National Army Museum is home to the skeleton of Napoleon’s famous horse, Marengo, which is depicted with the soon-to-be emperor in the famous 1801 painting by Jacques-Louis David. Captured after the Battle of Waterloo, Marengo remained in England, and after his death the skeleton was retained. It now sits in the museum’s gallery.

The “Changing the World” gallery has been officially combined with the previously known “Victoria Soldier” wing, and here visitors can take in objects from around the empire on which it often was said that the sun never set. It is worth noting that the reformation of galleries includes the rebranding of a large portion of the museum’s collection from a rather unpleasant period in British military history, namely the “Indian Mutiny.” Now called the “Indian Uprising,” the collection explores the reasons behind the 1857-1858 mutiny by the sepoys of the British East India Company. The gallery provides numerous fascinating pieces and helps provide further insights into the complex issue of the British Empire imperialism.

Not every piece is about glory and honor. In fact, some might best be swept under the rug. But in the interest of history, objects symbolizing English follies are on display as well as those celebrating the nation’s many triumphs. Notably, there is a handwritten order from General Airey and approved by Lord Raglan from the Crimean War. This is, of course, the infamous order for the charge of the Light Brigade at Balaklava on October 25, 1854. It reads: “Lord Raglan wishes the cavalry to advance rapidly to the front, follow the enemy & try to prevent the enemy carrying away the guns. Troop Horse Artillery may accompany. French cavalry is on your left. Immediate. R. Airey.”

The concise “World War” galleries show what it is was like for the average British Tommy during the two major conflicts of the 20th century, while the “Fighting for Peace” and “Modern World” galleries focus on the army after 1945. Of course, the end of World War II did not mean peace for the average British soldier, but the museum enables visitors to better appreciate the sacrifices that contemporary male and female soldiers make in the name of freedom.

Throughout the year, the National Army Museum hosts numerous exhibits that chronicle specific events and actions of the British military at various times from the 15th century to the modern day. Soon, visitors will get to discover a bit more about the infamous Redcoats during the American War of Independence. This is just one of several new exhibitions that will be opening. As with many museums, the galleries undergo regular changes so that visitors who previously have explored the National Army Museum may happily find something new.

One such new exhibition, part of Project Façade, is based on Dr. H. Gillies’s pioneering facial reconstruction work during World War I. The team at Project Façade has worked from original patient and surgical notes to tell the fragmented personal histories of the men who endured the long and painful reconstructive surgeries. “Many of the techniques pioneered by Dr. Gillies are used today during plastic surgery and for the treatment of returning facially injured servicemen,” says Mrs. Gillian Brewer, curator of the Department of Uniforms, Badges and Medals at the museum. “A small part of this exhibition will be shown concurrently at the Museum of Art and Design, New York.”

The National Army Museum also plans to continue telling the story of the modern-day British soldier in the exhibition “Helmand: The Soldiers’ Story,” put together in collaboration with the 16th Air Assault Brigade to explore the life and experiences of today’s servicemen and women in the Helmand Province, Afghanistan.

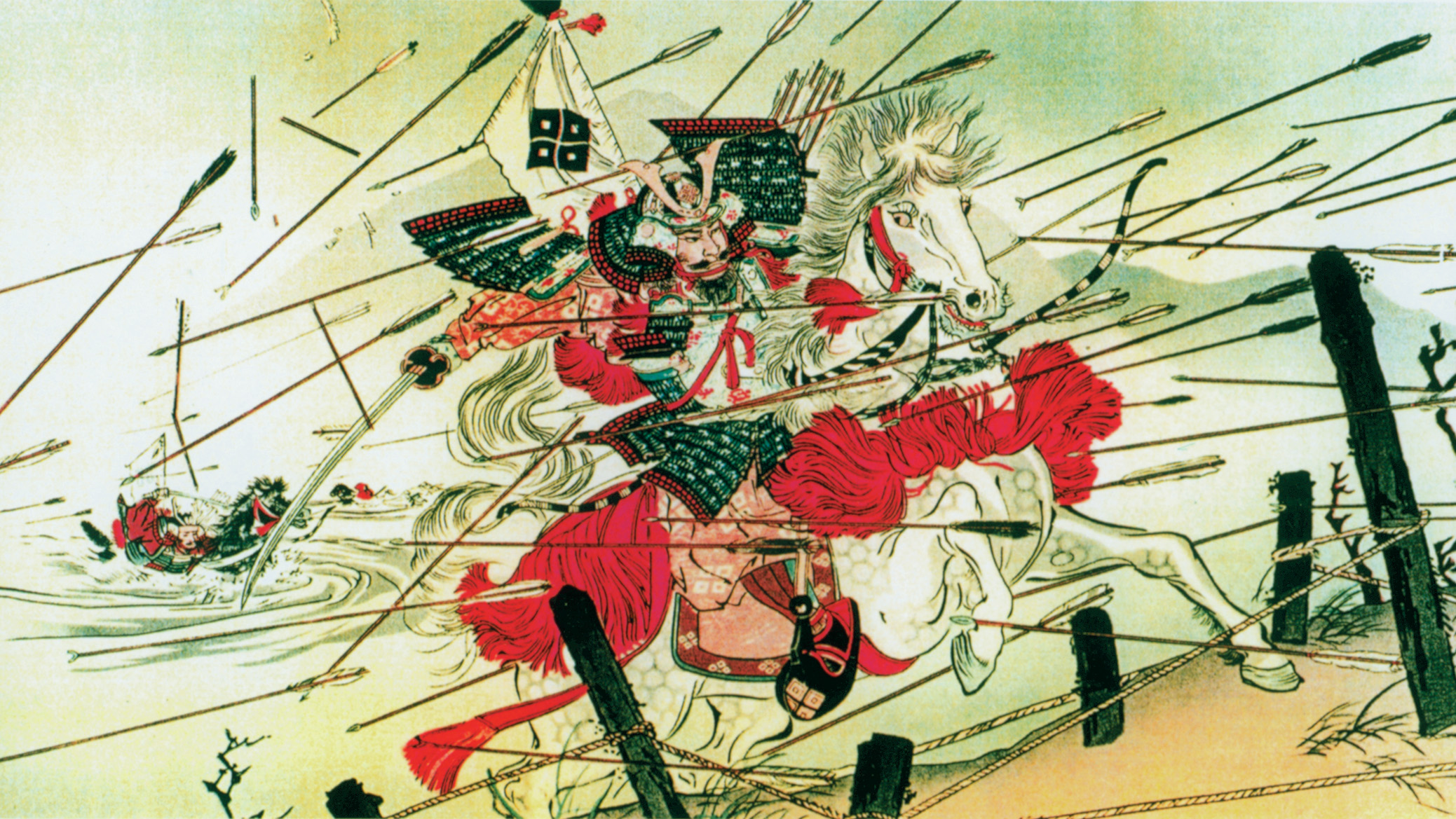

The sixth permanent gallery at the museum is also one that many visitors might not expect to find at an army museum. It is the museum’s art gallery, which displays numerous oil paintings and prints. As with the rest of the National Army Museum’s vast collections, the Department of Fine and Decorative Art contains some 50,000 prints, drawings, and watercolors, along with more than 835 oil paintings and miniatures. The department is responsible for maintaining the collection of items considered art, while working to acquire new pieces. And the collection isn’t limited to paintings. The artwork can be on paper, canvas, or wood, as well as sculpture, ceramics, or silver. Among the highlights of the collection is a silver tankard commemorating the Duke of Cumberland’s victory over Bonnie Prince Charlie at Culloden in 1746, which is particularly notable since no regiment has ever claimed “battle honors” for the engagement due to the harsh treatment of Jacobite forces and supporters following the battle.

Various pieces of art are interspersed throughout the museum, but most of the paintings are in the art gallery. One room—and an impressive room it is—is devoted to the fine artwork in the collection, including a portrait of Lt. Gen. Robert Monkton by American artist Benjamin West. “The gallery was redecorated in 2001 and reopened on 16 April 2002 by Sir Nicholas Goodison, the then-president of the National Art Collections Fund, the art charity which has helped us acquire a number of works of art over the years,” says Jenny Spencer-Smith, head of the Department of Fine and Decorative Art at the museum. The most famous painting on display is the fanciful but no less impressive work by Charles Edwin Firpp that dramatically depicts the Zulu victory at Isandlwana in 1879. In art, it seems, the British Army celebrates its defeats almost as greatly as its victories.

A Vast Collection

As with any museum, what you actually see is just a fraction of the collection. In fact, there is so much kept behind closed doors and in storage that it could equip an entire regiment. The Uniforms, Badges, and Medals Department collection includes more than 80,000 items of uniform and other garments, many dating as far back as the mid-17th century. This is currently one of the world’s largest collections of male uniforms, but also a significant collection of female military attire. Among the pieces is the coat that King William III wore at the Battle of Boyne in 1690, as well as more than 250,000 badges and 20,000 medals, including 37 Victoria Crosses.

“We hold 6.23 million items here at the National Army Museum,” says Brewer. “These range from tanks to photographs to plates with every imaginable, and some not so imaginable, items that the British, Indian, and Commonwealth Armies may have had cause to use. Only a small percentage of items can be on display at any one time; however, members of the public can and do make appointments to view other items from the collections either at the Museum or one of our two outstations.”

These two outstations are located on the outskirts of London, and each has enough items to fill any decent-sized museum in its own right. “Our main stores are located at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst,” adds Brewer, “and our new storage facility at Stevenage, where we house our Historic Military Vehicle and Sealed Pattern Collections. These sites are not open to the public, although members of the public are able to make appointments to view specific items from these collections.”

The National Army Museum seldom if ever divests any items from its collection. However, items are lent frequently to other institutions, including the Imperial War Museum and various regimental museums throughout the United Kingdom. Because most British Army regiments have long and often colorful histories, numerous artifacts have been gathered through the ages. But in recent years, due to the world’s changing political climate, many regiments are amalgamating, while some have disbanded entirely. Fortunately, institutions such as the National Army Museum ensure that their histories won’t be forgotten, nor will their artifacts end up in the rubbish bin or on eBay.

“It is true that as regiments amalgamate there is a possibility that one or more Regimental Museums may close,” says Brewer. “The National Army Museum in conjunction with the Ministry of Defence and other interested parties will ensure that items of importance will be saved in perpetuity.”

A Museum for All

The museum is very child friendly. In addition to numerous exhibits that allow and actually encourage touching—such items as a replica English Civil War “Lobstertail” helmet that visitors can try on—there are special activities for pre-teens. The museum hosts birthday parties and other special activities as well.

Serious scholars and those looking to conduct a bit more research in quiet can apply for a reader’s ticket to use the recently opened Templer Study Centre, which allows visitors an opportunity to explore the campaigns, personalities, and social history of the British Army. Located on the basement level of the museum, the research library has seating for 15 readers, who can access the archives of books, photographs, prints, and drawings while also obtaining help from the experienced curatorial staff. The Templer Study Centre is open on Thursdays and Fridays, and on the first and third Saturday of each month. Advance appointments are required to view items from the prints and drawings collections.

Additionally, much research can be done from afar as well. Thanks to the Internet, you don’t even need a plane ticket to discover some of the treasure that the National Army Museum has to offer. The staff has created an excellent website that allows visitors to explore the galleries, while also providing helpful research information. The museum accepts inquiries on collectibles and unit histories, and can even aids in tracking down information on individuals who may have served in the British Army.

As with any fine institution, the National Army Museum features a well-stocked gift shop that includes many excellent books on the history of the various regiments of the British Army, along with other gifts to remember your visit. The sun never set on the British Empire, and it may never set on the National Army Museum, either.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments