By Sam McGowan

Undoubtedly, the World War II aircraft type that attracts the most attention is the fighter plane. Yet, before the war, the U.S. Army Air Corps paid little attention to fighter development and tactics because its senior officers, with certain exceptions, would later lead the Army Air Forces with a sharp focus on bombers.

It was not until the success of Axis fighters in Europe and Asia revealed their value that more than a modicum of attention was paid to what American bomber crews in World War II came to know as “little friends.” Even then, it took a while for truly long-range fighters and effective fighter tactics to be developed within the U.S. Army Air Forces. Meanwhile, the ill-founded beliefs of senior officers who had placed their faith in daylight “precision” bombing without fighter escort, were sending young airmen to their fate in European skies.

As air force doctrine developed after the Great War, a major precept became “the bomber will always get through.” Coined as a phrase in a speech given by British politician Sir Stanley Baldwin before Parliament in 1932, the concept was based on theories of Italian airman Guilio Douhet, who advocated that air power was a decisive weapon that could operate in the third dimension unhampered by armies, navies, or natural obstacles to reach an enemy’s population centers and destroy the nation’s will to fight. While Douhet’s theory met with mixed reviews in Britain, it received a more favorable reception in the United States.

In 1920, the Air Service Field Officers School, later renamed the Air Corps Tactical School, was established at Langley Field, Virginia. Douhet’s theories received wide dissemination at the school, where a core group of instructors adopted them as the basis for strategy. The faculty was dominated by devotees of Brig. Gen. William L. “Billy” Mitchell, some of whom had participated in his test bombings of obsolete ships off Norfolk, Virginia. Actually, Mitchell never advocated reliance on bombers, but that did not stop some of his disciples from pursuing that line of thinking.

During the school’s first years of operation, the predominant theory taught was that pursuit aviation was to the Air Service what the infantry was to the Army. Attitudes had changed by 1926 when tactical school instructors started advocating that, in addition to striking at military targets, airplanes could bombard manufacturing facilities and other civilian targets. By 1931, air force doctrine held that once an air attack was launched it would be nearly impossible to stop.

The leading theorist was Major Harold L. George, who advocated that the bomber was the Air Corps’ primary weapon and daylight precision bombardment should be the air force’s primary mission. The list of other advocates reads like a who’s who of senior World War II U.S. Army air officers—Henry H. Arnold, Carl Spaatz, Ira Eaker, Haywood Hansell, and James H. Doolittle, among others. They came to be known as the “Bomber Mafia” by their opponents at the school, including George C. Kenney, who favored an air force designed to support ground forces; Lewis H. Brereton, who believed that air forces should be eclectic; and Claire Chennault, who was the primary advocate for the pursuit mission.

Others such as Frank Andrews, who was a strong believer in the bomber, leaned toward it as the primary weapon but believed that an air force should be balanced. Two other believers in an eclectic air force were Lieutenants Ben Kelsey, who worked with Doolittle in the Blind Flight Project and went on to become a leader in fighter research and development, and Gordon Saville, who worked closely with Kelsey and also taught at the Tactical School where he assumed Chennault’s mantle. By the mid-1930s, bomber advocates held sway over Air Corps thought, particularly after Chennault was medically retired.

In the mid-1930s, U.S. strategy was based on defending against invasion rather than waging an overseas war, and the Air Corps was authorized to purchase aircraft with this in mind. Providing escort for bombers was not a consideration. Invasion by sea, although remote, was a far greater possibility than air attack. Instead of developing pursuit ships designed to climb rapidly to high altitudes to intercept an enemy force, the emphasis was on rugged construction with heavy firepower for ground attack.

Lieutenant Ben Kelsey, as the Air Corps fighter projects officer, was responsible for developing new pursuit aircraft. He was particularly interested in Allison Engine Company’s work on inline liquid-cooled engines since they seemed to offer the best performance. He chafed at Air Corps restrictions that limited fighters to 500 pounds for guns and ammunition and pressed to have the restriction raised to 1,000 pounds. To get around the restriction, he and fellow lieutenant Gordon Saville formulated two new “interceptor” specifications, one for a single-engine airplane and one for a long-range multi-engine high-altitude fighter, which led to the development of the Bell P-39 Airacobra and the Lockheed P-38 Lightning.

In 1937, the Air Corps issued a specification for a fighter that could go into production quickly. Curtiss offered a version of their Hawk fighter, using Allison’s V-1710 engine, which became the P-40 Tomahawk. While the P-39 and P-40 were designed primarily for ground attack, the specification that led to the P-38 was for a long-range, high-altitude interceptor. All three types used the V-1710 engine. The P-39, however, was developed without a supercharger, although as a ground attack aircraft and low-altitude fighter it did not apparently need one.

In January 1939, using advances in aviation technology abroad as justification, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called for a military appropriation of $300 million to purchase aircraft for the Army. Less than three months later, Congress passed an emergency Army air defense bill authorizing the procurement of 3,251 aircraft. To speed up deliveries, Air Corps chief Maj. Gen. Henry “Hap” Arnold restricted purchases to aircraft already in or nearing production, which limited fighter purchases to P-39s and P-40s.

It was not until 1941 that the restriction was lifted, and the development and purchase of other types, particularly Republic’s robust P-47 Thunderbolt and the P-38, resumed. Little thought had been given to bomber escort. In fact, the Bomber Mafia believed the bombers of the day were so fast that it would be hard to intercept them and, if intercepted, their gunners would be able to fight off attacking aircraft.

At the time, the new war was still thousands of miles away in Asia and Europe. The only place where the United States had interests close enough to possibly be in harm’s way was in the Philippines, although the Panama Canal was a potential target. Until July 1941, the Philippines were not a priority for defense, but after President Roosevelt imposed an embargo on oil sales to Japan he decided to beef up defenses in the islands. When war came to the U.S., it came in the Philippines and the Netherlands East Indies.

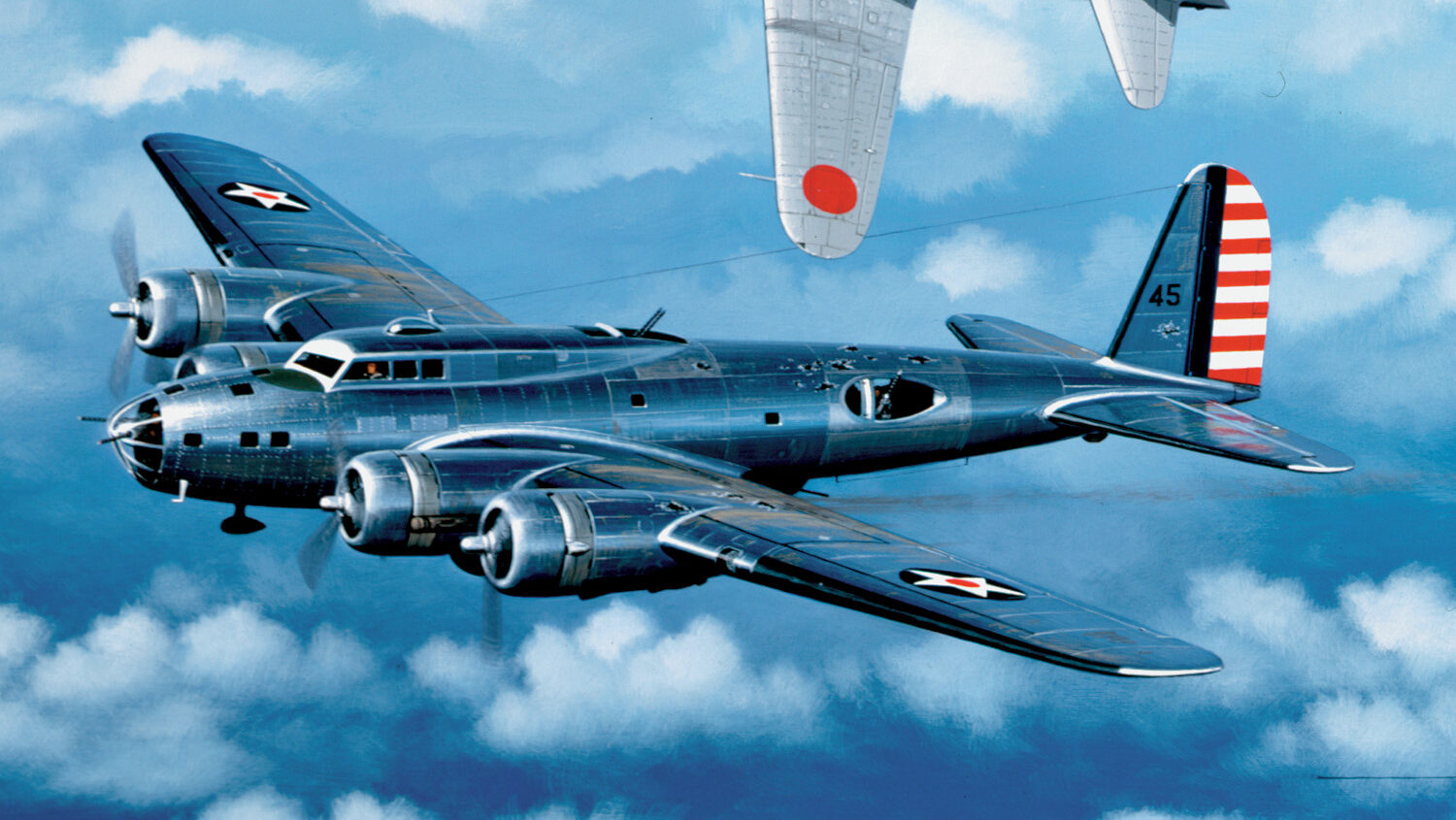

P-40s had some success in the Philippines in spite of inexperienced pilots and airplanes with engines that had not been broken in, but losses could not be replaced. Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and Consolidated LB-30/B-24 Liberator bombers operated unescorted against Japanese targets in Java and held their own but not without six losses to fighters. They were operating under the command of Maj. Gen. Lewis Brereton, who was all for using escorting fighters, but all he had were P-40s and P-39s, and there were not enough experienced pilots to be effective.

By the spring of 1942, a substantial fighter force had been built up in Australia. They were P-40s and P-39s, along with some 200 P-400s (P-39s that originally had been built for the British and were lighter armed than the U.S. version). While they were ineffective defending against Japanese bombers attacking Port Moresby at high altitude, the P-39/P-400s were successful in the escort role on missions to the other side of the Owen Stanley Mountains and on strafing missions. P-39s/P-400s were used extensively to attack ground targets in New Guinea and on Guadalcanal. It was not until the Air Staff finally sent P-38s to the Southwest Pacific that autumn that Allied airmen began gaining the upper hand over the Japanese. Meanwhile, Claire Chennault’s American Volunteer Group and 23rd Fighter Group used his tactics to achieve considerable success in Burma and China with their P-40s.

American aircraft first saw action against the Luftwaffe in the Middle East, where Brereton transferred in June 1942, in response to the British defeat at Tobruk. His Middle East Air Force’s (MEAF) mission was to support British operations in Egypt and Libya. MEAF included two P-40 groups, but they operated under RAF Middle East Command control primarily for ground attack and providing air cover at low altitudes. The only high-altitude fighters available were RAF Supermarine Spitfires, which lacked the range to go with MEAF’s B-24s to their targets.

In November 1942, MEAF became the Ninth Air Force. It continued a dual mission of supporting the British with its P-40s and light and medium bombers while mounting unescorted attacks on strategic targets with the heavy B-24s. The use of fighters, particularly P-40s, for ground attack had become the primary fighter mission in the Mediterranean by mid-1943, but it was not until the spring of 1944 that such missions became primary in Western Europe, where fighters had been used mostly for escort.

Although the United States formally entered the war on December 8, 1941, it was not until August that heavy bombers commenced operations out of the United Kingdom. Only four fighter groups—the pursuit designation was changed to fighter in early 1942—were part of the initial move of Eighth Air Force units to Britain. One operated P-38s while the others had P-39s before they left the United States. Originally, the P-39s were supposed to go to the United Kingdom by ship, but at the last minute the Air Staff decided that two groups would leave their airplanes behind and they would be equipped with Spitfires when they arrived. All four groups moved to North Africa to join the Twelfth Air Force, as did a second P-38 group that arrived later in the summer. The Air Staff also decided to form a new group in the United Kingdom made up of former RAF pilots and Spitfires. Eighth Air Force activated the 4th Fighter Group in September. After the other groups left for Africa, the 4th was the only Army Air Forces group left in the United Kingdom. A third P-38 group arrived in September but also transferred to North Africa.

In early November, American and British troops landed in northwest Africa during Operation Torch. All three P-38 groups, two Spitfire groups, and the P-39 group left England for Algeria to join the Twelfth Air Force. Bomber groups arrived throughout the summer, but it was not until the end of November that a fighter group arrived. The 78th Fighter Group was an experienced P-38 group, but shortly after it arrived its airplanes and most of its pilots went to North Africa. The group re-manned and equipped with P-47s. The transition took place in January 1943, right after the 56th Fighter Group arrived. The 4th Fighter Group also transitioned into Thunderbolts. To say the pilots were not happy to lose their Spitfires is an understatement!

The Republic P-47 was a radical departure from the Allison-powered fighters that had become standard in the Air Corps. Initially, Republic planned to develop a new fighter based on its P-35 using the Allison inline engine. After the Army expressed reservations about the XP-47, Republic decided to adapt it to the new Pratt and Whitney Double Wasp engine, a large radial engine with double-banked cylinders. The new P-47 was the largest fighter ever built to that time—it grossed out at 11,600 pounds (eventually increased to 17,500 pounds). The Army was impressed by its performance and issued a contract for 773 airplanes; by the war’s end, more P-47s would be produced than any other fighter. Although the P-47 was heavy, it was fast, with a top speed of 427 miles per hour, but its climb performance was less than desired. On the other hand, it could dive—so fast that it started nibbling on the edge of the speed of sound and encountered compressibility. The air-cooled radial engine turned out to be better suited to combat operations than liquid-cooled engines, which would overheat and seize if the coolant was lost. The first fighter group to equip with the new Thunderbolt was the 56th.

Although the three P-47 groups began training in the United Kingdom in January and February, they did not become operational until April. Several milk run missions were flown along the French coast with RAF Spitfires to allow the pilots to become accustomed to combat conditions. The first pilot to down a German fighter was Major Don Blakeslee of the 4th Fighter Group. He spotted three Focke-Wulf FW-190s and used his airplane’s diving speed to catch up with one and shoot it down.

Two other 4th Fighter Group pilots also put in claims. After the mission, Blakeslee was widely reported as saying, “It ought to dive, it sure can’t climb.” Even though Blakeslee and other former RAF pilots were not fond of the Thunderbolt, the men of the 56th were, and they began racking up the highest number of kills of any fighter group assigned to VIII Fighter Command and producing the most American aces of the war. On May 4, VIII Fighter Command’s P-47s escorted B-17s to Antwerp. None were lost; the only casualty was a P-47 that suffered an engine failure. Over the next month, encounters with German fighters increased and victories mounted but so did losses since the young Americans were fighting far more experienced Germans. Some losses were attributed to engine failure.

Bomber Mafia members believed strongly in daylight bombing without fighter escort even though the RAF had learned it was too costly early in the war when casualties were so severe they turned to night operations. They encouraged the Americans to do so as well, but Generals Spaatz and Eaker, the two senior air officers in Britain at the time, were determined to prove the theory in combat. In the summer of 1943, Eaker ordered deep-penetration missions into Germany with disastrous results. Escorting fighters could operate just beyond the German border, but not by much. The Luftwaffe knew the fighters’ range limitations and planned interceptions of bomber formations after they turned back. The VIII Bomber Command suffered heavy casualties as a result.

Earlier in the year, the Eighth Air Force Technical Section began addressing the use of drop tanks to increase range. Although P-38s and P-39s had been fitted with external tanks for ferrying, P-47s were initially shipped by sea, and no tanks were sent with them. Colonel Ben Kelsey, the technical section commander, requested tanks from the United States and put his assistant, Lt. Col. Cass Hough, in charge of testing them. The resonated paper tanks, which held 200 gallons of gasoline, proved unsatisfactory because reduced atmospheric pressure at high altitudes prevented fuel from transferring. They were prone to leak and produced a significant amount of drag, which increased fuel consumption. To solve the problem, Hough requested new tanks from the United States and also went to the British for help.

Hough and his assistant, Lieutenant Robert Shafer, soon realized that for external tanks to work they had to be pressurized. Due to the urgency of the situation, they chose to ignore Army regulations prohibiting pressurizing fuel tanks and developed their own pressurized tanks. Working with British engineers, they came up with a means of using exhaust air from the instrument vacuum pump to pressurize the tanks. On May 20, the prototype of an all-metal, 100-gallon tank capable of providing fuel up to 35,000 feet arrived in Britain. Plans were made to have the tanks produced in Britain, but a shortage of sheet metal caused a three-month production delay. Meanwhile, more than 1,100 unpressurized 200-gallon tanks arrived. Although they could not be used above 23,000 feet, Hough suggested using them during climb-out. There was not enough time to consume a full 200 gallons by the time the fighters reached hostile airspace, so the tanks were only partially filled. The procedure increased the Thunderbolt’s range by 75 miles.

On August 17, a shipment of metal tanks arrived. They were designed for P-39s and P-40s but were easily adaptable to P-47s. Although they only held 85 gallons, that was roughly the amount carried in the 200-gallon tanks. The new tanks produced less drag and only reduced airspeed by 12-15 miles per hour. The British offered a paper tank with a capacity of 108 gallons; by the end of September, the 4th Fighter Group was using them. The extended range allowed fighters to penetrate German airspace for the first time on September 27 on a mission to Emden. The force met stiff opposition, but losses were kept to seven bombers and two fighters; the P-47s claimed 21 German fighters destroyed.

On October 2, the 56th Fighter Group flew a mission to Emden with the 108-gallon tanks, an overall distance of 750 miles. By burning their tanks empty, P-47 pilots were able to fly missions 375 miles from their base while the 85-gallon tanks allowed missions to 340 miles. This was some 200 miles short of Berlin, but P-47s were now able to accompany bombers well into German airspace. Long-range escort fighters were beginning to arrive in the United Kingdom as two P-38 groups, the 20th and 55th, joined VIII Fighter Command. Meanwhile, bomber losses mounted.

On October 15, the day after a disastrous mission to Schweinfurt, the 55th Fighter Group became operational with its complement of 75 P-38s. With drop tanks, they had a combat radius of 450 miles, which was getting close to Berlin. A second P-38 group, the 20th, became operational in December. New tactics were developed using P-38s to protect the bombers over their targets while P-47s covered the bomber stream at the points where fighter attack was most likely. By November 1, 1943, P-47s had accounted for 237 German aircraft against a loss of 73 of their own. While this number seems small in comparison to later totals, it was because German pilots refused to engage fighters but waited until they started turning back to attack the bombers. Additional fighter groups arrived in Britain in the fall, most with P-47s. The VIII Fighter Command was authorized to maintain 15 groups, but that figure was not reached until the spring of 1944.

Improvements were made to the P-47, including injecting water into the engine cylinders, which boosted power by 200-300 horsepower, thus increasing performance. A larger four-bladed propeller gave the P-47 greatly improved climb performance. The heavy fighter’s range was increased by the addition of two more drop tanks, one under each wing, in addition to the one under the belly. Although it was not until April 1944 that all P-47s had been modified to carry wing tanks, enough had been modified by February that VIII Fighter Command was able to take advantage of them by assigning groups to different positions along the bomber stream in relation to their range.

In September 1943, a turn of events brought large numbers of additional fighters to Britain. In preparation for the upcoming invasion of France, the Ninth Air Force transferred to England from the Middle East to develop a new tactical air force. Original War Department plans were for the Eighth Air Force to switch from the strategic to the tactical role to support the invasion with its VIII Air Support Command, but a new plan led to the establishment of a second numbered air force dedicated solely to tactical operations. The transfer was only of the Ninth’s headquarters, which was still commanded by Brereton, and IX Fighter and Bomber Commands without equipment or personnel. Brereton’s new air force would consist of fighter bombers, light and medium bombers, and troop carriers to support airborne operations and provide logistical support for his other units once they had crossed the English Channel to France.

The Ninth Air Force eventually included IX Fighter Command and two tactical air commands, IX and XIX. The Ninth was supposed to operate as an independent command in conjunction with Royal Air Force units reporting to Air Marshall Trafford Leigh-Mallory, who had been appointed to command the Allied Expeditionary Air Force (AEAF) for the D-Day invasion, but the issue became political in February 1944 when General Carl Spaatz, who had been named commander of a new organization called U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe, maintained that the Ninth should be under his administrative control. Another political issue involved Brereton’s new North American P-51 Mustang fighters.

There is a common misconception that the P-51s with Rolls Royce Merlin engines were developed solely to be escort fighters and that as soon as they appeared in the skies over Europe the Allies won air superiority. This, however, was not the case. The design came about when North American Aviation president Dutch Kindleberger took exception to a Curtiss offer to allow his company to produce P-40s under license for sale to the British. Kindleberger proposed that his company instead design and produce a new fighter with the same engine around a new wing. He promised to have the first one ready in four months.

North American Aviation’s new design, which was given the U.S. designation P-51, proved to be fast and maneuverable, but it suffered a lack of performance above 15,000 feet because the Allison engines were not turbocharged, so the RAF assigned its new Mustangs to ground cooperation squadrons. Because of its range, the Air Staff decided to adapt it as a dive bomber with the designation A-36. A British test pilot recommended that the RAF modify a Mustang with a Rolls Royce engine to correct the lack of high-altitude performance. The modification was successful, and the Army Air Forces decided to evaluate the conversion.

Volumes have been written about the P-51 with the Merlin engine and how it was developed to be a long-range escort fighter; General Arnold even indicated as much in his memoirs. The problem is that this is simply not true. By the time it entered service, the focus had switched to the fighter bomber, which had proven so effective in North Africa and the Middle East. At the Trident Conference in May 1943, the Combined Chiefs agreed to mount a cross-Channel invasion of France in the spring of 1944 after an invasion of Sicily in mid-1943 and a subsequent move onto the Italian peninsula. During the interim, RAF Bomber Command and VIII Bomber Command would mount a combined bomber offensive, but as the date for the invasion approached the emphasis would switch to preparations for it. In a letter to Eighth Air Force commander Eaker in September 1943, AEAF commander Leigh-Mallory outlined the role of fighter squadrons: provide fighter cover over the beaches; provide fighter cover for the shipping lanes leading to the beaches; make fighter bomber attacks against enemy ground forces and installations; provide fighter escort for light and medium bombers; and provide reconnaissance.

Providing escort for heavy bombers was not even mentioned. Leigh-Mallory realized that prior to, during, and after the invasion the heavy bombers’ role would be to support the ground forces. In fact, Eighth Air Force’s mission all along had been to prepare for an invasion of France. Although historians have not addressed the issue, the decision to discontinue daylight bombing operations deep into Germany may have been prompted as much by the upcoming change in mission as it was by the heavy losses taken in the late summer and fall of 1943. Leigh-Mallory also addressed the P-51s, stating that they appeared equally suited for fighter escort and the close air support role and should be under a single commander.

When the Air Staff began allocating aircraft for Ninth Air Force, all of the new P-51 groups were dedicated to it. It was a logical decision since the Ninth’s role prior to the invasion would be attacking German lines of communication throughout Western Europe and the RAF’s Mustangs were going to II Tactical Air Force, Ninth’s counterpart.

The P-51s’ increased range would allow them to operate well into Germany on tactical missions; in preparation for the invasion, all missions would be tactical. In October 1943, the first of the Ninth’s P-51 groups, the 354th, arrived in the United Kingdom, although it was not until the following month that its airplanes arrived. Since it was a new group, a few VIII Fighter Command pilots were temporarily attached to it to help its pilots gain experience. One was Lt. Col. Don Blakeslee. He never had liked the P-47s he had been flying for the past year, but the new Mustangs reminded him of the agile Spitfires he had started out in. Blakeslee, who was not a tactician and evidently did not understand the Ninth’s role in the upcoming invasion, mounted a campaign to have the P-51s reassigned to VIII Fighter Command. He pressed his case to VIII Fighter Command’s leader, Maj. Gen. William Kepner, who went to Spaatz, who appealed to the Air Staff, which told him no.

While Spaatz was unable to have the 354th transferred to VIII Fighter Command, he managed to convince the Air Staff to let him swap a P-47 group, the 358th, for the recently arrived 357th Fighter Group. Spaatz finally persuaded the Air Staff to reallocate the 33 fighter groups that were planned to be assigned to Britain. The Eighth Air Force would get seven P-51 groups instead of none along with four groups each of P-38s and P-47s. The Ninth would have 13 P-47 groups, three of P-38s, and two of P-51s. Those numbers would change after the invasion when a need developed for additional P-47s and P-38s in the fighter bomber role and the P-51 proved vulnerable on low-altitude operations.

Except for the 56th Fighter Group, all of VIII Fighter Command’s groups were equipped with P-51s by the end of the war, and their P-38s and P-47s were transferred to Ninth Air Force. The reequipping was at least in part due to General George Kenney’s refusal to accept P-51s in the Southwest Pacific, where the P-38 remained the primary fighter, but it was also due to the Mustang’s vulnerability in the tactical role.

It was not until May 1944 that all of the Ninth’s groups arrived or that VIII Fighter Command had received its seven groups of P-51s. Consequently, the P-38 and P-47 groups were most responsible for gaining air superiority over Germany. Throughout the winter and early spring of 1944, escort missions were scheduled so that the predominant P-47s would escort the bombers through areas most prone to fighter attack while the long-range P-38s and P-51s protected them over the targets. VIII Fighter Command’s fighters were not alone in the escort role; the Ninth Air Force’s fighters were also flying escort, as were RAF squadrons, some of which were equipped with Mustangs.

In his New Year’s address to Army air units, USAAF commander Arnold stressed that the mission of air forces in Europe was to destroy the Luftwaffe “in the air, on the ground and in the factories.” Lt. Gen. James H. Doolittle arrived in England on January 6, 1944, to take command of VIII Bomber Command, which would soon be elevated to become Eighth Air Force when the original headquarters became USSTAFE. Sunday, February 20, 1944, kicked off a week of air attacks on German aircraft factories that became known as Big Week. Its purpose was to carry out Arnold’s intentions. Over a five-day period, Eighth and Ninth Air Force fighters flew 3,839 sorties—only 425 were by P-51s.

Doolittle was eager to mount an attack on the German capital of Berlin, which had yet to be visited by the Eighth Air Force. The mission was originally scheduled for March 3, but bad weather over Germany caused an abort. The following day turned out to be just as bad, and another recall was sent out, but one combat wing of B-17s allegedly failed to get the message. When Eighth Air Force realized some bombers were not turning back, they allowed part of the fighter escort to continue to Berlin.

The 4th Fighter Group, which had just converted to P-51s, and the 354th Fighter Group were in the vicinity of Berlin, but it was the 55th Fighter Group’s P-38s that actually got over the city. On March 6, a mission was finally flown over Berlin, and it turned out to be an even worse disaster than the Schweinfurt mission the previous October, even though the bombers were escorted all the way to and from the target.

Sixty-nine bombers and 23 fighters were lost, while a number of others failed to return to their bases due to battle damage. Another mission two days later also resulted in heavy losses; 37 bombers and 11 fighters failed to return. Losses on the two missions amounted to 106 bomber crews and 34 fighter pilots, a total of 1,094 men missing in action, not to mention the airplanes that had to be scrapped and those that came back with dead and wounded crewmen.

The two missions were evaluated in both England and the United States to determine why so many bombers had been lost even though they were escorted. It was determined that the fighters operated too close to the bombers and were unable to get into position to break up attacks. Consequently, new fighter tactics were developed. Instead of sticking close to the bombers as they had been doing, some fighters went out well ahead of the bomber streams to intercept German fighters as they were assembling, while others ranged above and off to the sides of the bombers, sometimes so far away that the crews could not see them.

The change in fighter tactics was met with a lack of enthusiasm by the bomber crews, who felt they were being left unprotected. Many accused Doolittle of using them as bait, a belief that was not that far from the truth since the rationale for the Berlin mission and others into Germany at the time was to draw the Luftwaffe into combat and reduce its fighter strength through attrition. The new tactics worked, and German fighter losses mounted. More than 500 of Germany’s best pilots were lost, a loss that could not be overcome. Bomber losses reached their peak in April then declined.

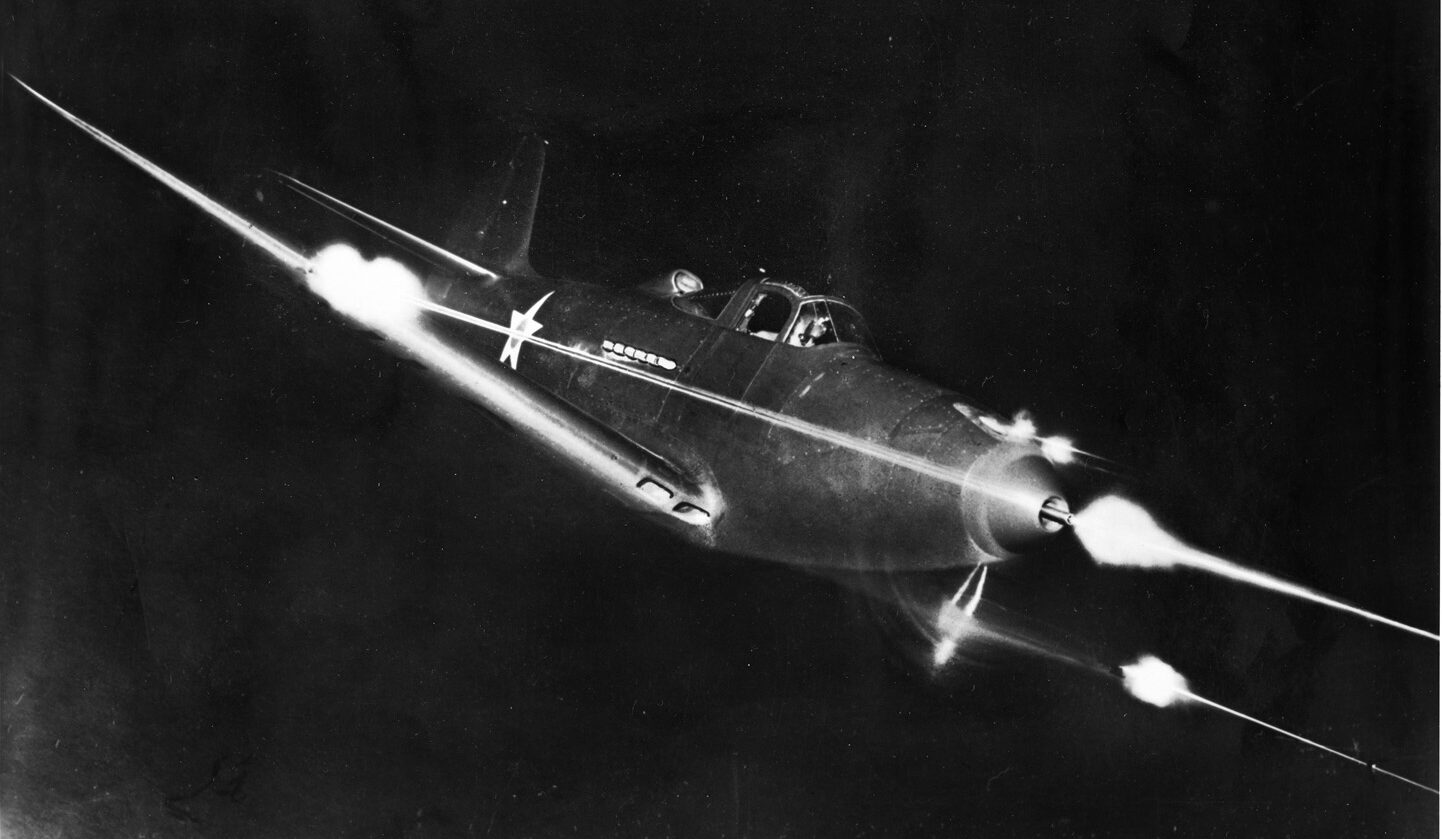

In another move to inflict damage on the Luftwaffe, escort fighters were encouraged to drop down on the deck during their return flight and expend their ammunition strafing airfields and other targets, particularly locomotives. Fighter pilots were admonished that it did not matter whether an airplane was destroyed on the ground or in the air. For a few weeks in March and April, a special unit made up of volunteers from four P-47 groups practiced strafing. After the P-47 groups pioneered ground attack missions, the 4th Fighter Group got permission to fly strafing missions against German airfields in France.

The P-38-equipped 20th Fighter Group flew a strafing mission deep inside Germany only 80 miles west of Berlin. Soon, fighter sweeps over France and even deep into Germany were regular occurrences. Experiments were also conducted with bombs, which had been standard practice for P-40s in North Africa and the Mediterranean. Fighters were adapted to carry high-velocity rockets to attack tanks and other targets. Experiments were also conducted with level bombing by fighters dropping when a modified P-38 with a bombardier on board dropped its bombs. The “droop snoot” P-38s not only led P-38 formations, but also led formations of other fighters, particularly P-47s.

In October 1943, the War Department authorized a new air force in the Mediterranean. Fifteenth Air Force was set up using the Twelfth’s B-17s and two B-24 groups that had been with the Ninth. Finding fighter groups for escort duty was a problem. The Air Staff reassigned six groups that had previously been with the Ninth and Twelfth, three of P-38s and three of P-47s, but priority for fighters was given to Britain due to the upcoming invasion. The only group still in the United States not allocated to an overseas air force was the 332nd Fighter Group, an African American unit. In late 1943, Spaatz asked to have it assigned to Italy to XII Fighter Command. There was already one African American fighter squadron in Italy, the 99th, which had been attached to several different groups. The 99th’s record in ground attack was poor, but in January the squadron put in a good showing against German fighter/bombers over Anzio.

Senior air force leaders reasoned that the 332nd might be better suited to the air combat role and reassigned it to the Fifteenth Air Force. At the time, the 332nd was flying P-39s while the 99th was flying P-40s, but they both briefly transitioned into P-47s and then into Mustangs. The 332nd began flying escort missions in early June, and the 99th joined it in July. The 332nd was the only new fighter group to join the Fifteenth Air Force. It gave the Fifteenth a fourth fighter group and four additional squadrons. By mid-July, the Fifteenth’s P-47 groups had all transitioned into P-51s, while their P-47s went to Twelfth Air Force, which, like Ninth Air Force in Britain, had become a tactical air force.

There is a common misconception that P-51s were used primarily for escort duty because they were superior in the air-to-air combat role. Actually, although the Mustang had greater range, the transition into P-51s was because they were less suited for ground attack due to their liquid cooling system, which made them vulnerable. A single hole in the cooling system could cause a complete loss of coolant followed by an engine failure. Of the two groups that served longest with VIII Fighter Command, the 4th lost twice as many fighters as the 56th, which operated P-47s for the entire war, while the 4th was the first of VIII Fighter Command’s groups to convert to P-51s. Spitfires, which used the same engines, also proved unsuited for ground attack missions for the same reasons.

The Hawker Typhoon also had a liquid cooling system, but it had been modified for ground attack so the RAF was forced to make do with it. The P-38 also featured liquid cooling, but with two engines a pilot at least had a chance to make it to a friendly base if one failed. The P-38’s concentrated fire and 20mm cannon made it an effective ground attack aircraft.

The P-38’s record in Europe is somewhat checkered, although in the Pacific it was the preferred fighter due to its long range and the safety provided by the second engine in an environment where missions were flown over long stretches of open water. Although P-38s were assigned to Eighth Air Force at the beginning of its service in the United Kingdom, they all transferred to North Africa in late 1942 and it was not until nearly a year later that any were assigned to VIII Fighter Command, when the 20th and 55th Fighter Groups arrived. They offered new escort possibilities due to their much longer range; with external tanks, they were able to go 100 miles farther into Germany than P-47s.

However, early VIII Fighter Command P-38 operations were plagued with mechanical problems. The cockpit heaters were ineffective in the severe cold over Europe, where air temperatures can be 50 degrees or more below zero. The cold caused engine problems as lubricating oil thickened and led to failures. The turbochargers also gave problems.

The P-38s were not the only fighters to suffer problems due to cold. So did the P-51s. Yet, even though Eighth Air Force was lukewarm to the Lightning, the three groups that moved to North Africa operated them for the duration of the war with considerable success. After escorting Northwest Africa Air Forces heavy bombers, the three P-38 groups were reassigned to the Fifteenth Air Force when it was formed and served as almost half of its escorting fighter force.

Not the least was the decline in quality of the Luftwaffe’s fighter force due to heavy losses among its experienced pilots. Strafing of airfields also had a major impact; more aircraft were destroyed on the ground than in the air. German aircraft losses were covered by factories as fighter production continued right up to the end of the war, but experienced pilot losses could not be overcome.

Another factor was the interruption of petroleum supplies, both by attacks against the Romanian oil industry and the destruction of locomotives and tank cars. Fuel shortages reduced training hours for Luftwaffe pilots. While new American pilots had an average of 120 hours in fighters by the time they entered combat in 1944, Luftwaffe pilots had less than 30. When Soviet forces captured the Romanian oil fields in August 1944, German gasoline supplies were cut to the bone. Consequently, the Luftwaffe kept its fighters on the ground unless a mission was headed for certain targets, particularly Berlin. The Luftwaffe deployed jet fighters in late 1944, but their high fuel consumption and limited endurance reduced their effectiveness.

Escort fighters were never the problem in the Pacific that they were in Western Europe. Although missions were much, much longer, they were mostly over open water until reaching the target area, so the bombers were not prone to interception as early in the mission. Fighter range was greater because they did not have to weave over the bombers to protect them. General George Kenney, the senior air officer in the Southwest Pacific where most of the air action took place, was not locked into the daylight precision bombing theory. Until P-38s became available for escort, he instructed his bomber commanders to schedule missions so their bombers came over the target in darkness or right at daylight while the Japanese were still asleep.

Missions over New Guinea were escorted by P-39s and P-40s. Beginning at the end of December 1942, long-range P-38s became available and the Allies quickly gained air superiority. The Fifth Air Force also began receiving P-47s. In mid-1944, Charles Lindbergh visited the theater as a technical representative for Chance-Vought and got permission to fly with the P-38 squadrons. He taught Kenney’s fighter pilots how to extend their range greatly by using power control techniques he had learned during his record-setting flights.

Lindbergh, who was experienced with the P-47 and the Double Wasp engine, taught fuel-saving techniques to P-47 pilots as well. Consequently, Fifth Air Force fighter pilots operated at much greater distances from their bases than their counterparts in Europe. When he was offered P-51s, Kenney refused them. He had settled on P-38s as his primary fighter due to the long overwater missions his pilots were required to fly. The loss of an engine on a single-engine fighter over shark-infested waters or the dense tropical jungles was a death sentence. It was not until early 1945 that the Fifth Air Force received any P-51s, except for those assigned to reconnaissance squadrons as F-6s.

Fighters played a major role in China starting in early 1942, when Claire Chennault’s American Volunteer Group (AVG) went into action with their P-40s. In July, the AVG was brought into the U.S. Army as the 23rd Fighter Group, although most of its pilots went back to the States or went to work for China National Airways Corporation. Since all fuel and other supplies had to be flown to China from India, fighters were better utilized due to their lower fuel consumption. Initially, fighters in the CBI were P-40s, but as new types became available they were joined and eventually replaced by P-47s, P-38s, and P-51s.

In the summer of 1944, Boeing B-29 Superfortresses commenced operations against Japan from China, then later in the year from the Mariana Islands. Not even the vaunted Mustang had the range to reach Japan from the Marianas, but some had been assigned to the Seventh Air Force to escort its Liberators (there were no B-17s in the Pacific after 1943).

As it turned out, the B-29s faced a much smaller Japanese fighter force than expected, and losses to fighters were light. Nevertheless, one of the reasons given for the capture of Iwo Jima was that it could serve as a base for P-51s for missions to Japan. However, the escort issue soon became moot.

In March 1945, XXI Bomber Command turned to night operations at low altitudes, and the Mustangs were used primarily for fighter sweeps. Once Okinawa fell into Allied hands, Fifth Air Force fighters moved to bases there and on nearby islands and began flying strafing and bombing missions against Kyushu, where the planned invasion of Japan was supposed to take place.

On August 5, 1945, the day before the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Fifth Air Force pilots came back from their missions to report that white flags of surrender had been laid out all over Kyushu.

Author Sam McGowan is a veteran and licensed pilot. He has written on numerous topics for WWII History and resides in Missouri City, Texas.

Almost as faulty as the American opinion of bombers, was the German reliance on fast twin engine bombers for strategic operations. While the Germans were successful in blitz operations on the continent against the Western countries, they were quite ineffective against the Spitfires and Hurricanes of Great Britain and little better against the dispersed Russians. Seems the theorists ignored the progress of fighters between the wars which had heavier guns, faster speed and better altitude performance.